Laid to rest in a bed of flowers

The colourful history of Neepawa's cemetery — one of the prettiest in Manitoba — draws visitors from all over

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/09/2015 (3725 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

NEEPAWA — Headstones can make for interesting reading.

Take this rhyme from the headstone of John James Black, b. Apr. 4, 1860; d. Dec. 9, 1934, in Neepawa’s Riverside Cemetery.

“Reader behold as you pass by,

As you are now, so once was I.

As I am now, so you must be,

Prepare for death and follow me.”

OK, John, but forgive us if we foot-drag a bit on the following part.

A sadder epitaph reminds us not just of our mortality, but that of children, especially in earlier times.

The tombstone is of two boys. You have to get down on all fours to read the epitaph. It’s on a thin, grey slab of granite, with crusty lichens crept into the crevices of the chiseled letters.

Percy A. Campbell, aged “5 years, 9 months, and 5 days,” and his brother Colin, aged “1 year, 3 months, and 17 days,” died a day apart: Feb. 3 and 4, 1893.

“How much of light, how much of joy,

is buried with our darling boys.”

There was a lot of that back then, said Jack Follows, 64, who has been caretaker of the Riverside Cemetery for 36 years, and who still dug the graves with spade and shovel up until about five years ago.

“There are a lot of graves here where siblings died within days of each other. It could have been flu, or diphtheria, or anything back then,” he said.

Riverside Cemetery is often called the most beautiful cemetery in Manitoba, but let’s not stoke controversy. Let’s just say it’s one of the most beautiful. Of that there’s no debate. Every year, the town plants about 60,000 petunias around the cemetery graves. It’s quite a sight.

The best vantage of the 138-year-old cemetery is to walk from east to west. The east side is on a bit of rise and you can look over the thousands of flowered graves. It looks more like a pageant. It’s almost like overlooking a flotilla, with ships garlanded in red, white, fuchsia, mauve and violet flowers.

The reason is Neepawa has had a unique policy of “perpetual care” since about 1952, said local historian, Cecil Pittman. Every municipal cemetery has some kind of perpetual care policy. In exchange for purchasing a burial plot, a town agrees to cut the grass and straighten the headstones, among other things. In Neepawa’s case, town councillors wanted to take it a step further and plant petunias in front of each grave.

Some councillors balked at the idea at the time. Did the town know what it was getting into? What would be the cost to plant and tend flowers on all the graves in perpetuity? Forever is a long time.

But perhaps flowers are just in Neepawa’s DNA. After all, it ran the popular Lily Fest for 18 years, until this year. The bylaw passed and there’s no turning back for subsequent councils. “They’re stuck with it,” said Follows, in his plain-spoken manner.

The petunia project is an extraordinary undertaking for a town of less than 5,000 people. It started with a perpetual care fee to the bereaved families of about $25, according to Pittman. The fee today is $1,250, and the perpetual care fund now totals over $1.4 million. Only the interest can be used to defray cemetery costs, and it doesn’t come close. The interest pays just $20,000 to $25,000 of the cemetery’s annual $250,000 costs, said town chief officer, Colleen Synchyshyn.

The petunias are a big part of that, not just the plants themselves that cost over $15,000 annually, but the staff needed to plant, weed and water them. For example, Neepawa actually planted more than the usual 60,000 flowers this year because planting had already begun when a severe frost struck. So they had to start again. The summer’s heavy rainfall has caused other problems, such as weeds.

About 10 cemetery staff are needed from the start of May to October to tend the cemetery. But when we visited, their ranks had swollen to 17 to help weed the flower beds. They must weed over 3,600 flower beds, containing 15 petunias each.

The town is looking at ways to cut costs through efficiencies or technology. For example, they still water flowers by hand. Underground pipes send water to spigots scattered through the cemetery. Employees attach a 100-foot hose to the spigot, and stand there spraying the flowers back and forth.

Of course, flowers aren’t the only attraction at Riverside Cemetery. The presence of Margaret Laurence looms large here.

“What brought us here? The Lily Nook (the famous lily garden centre in Neepawa) and Margaret Laurence,” said Bev Denesik of Saskatoon, spotted wandering among the tombstones.

The Neepawa cemetery houses the grave of not just Margaret Laurence but the “Stone Angel” that her famous novel is named for. Denesik and friend, Iona Baraniuk, of Sheho, near Yorkton, visited Riverside Cemetery to see the stone angel.

The angel doesn’t have wings, as it does in the novel. Nor is she “eyeless,” as Laurence described her. Her hair is long, her eyes downcast, and her raiments flow to her bare feet. She shoulders a large cross. The statue looms over the cemetery.

Is it really an angel? An angel has wings.

Pittman says it has been called an angel since he was a kid, and that was some 70 years ago, before Laurence’s novel. The stone angel actually marks the grave of John Andrew Davidson, b. Aug. 19, 1852, d. Nov. 14, 1903. He was provincial finance minister in 1900 for a Conservative government but died shortly after being re-elected in 1903.

Laurence, a native of Neepawa, is buried not far away with her Wemyss family (her maiden name). It’s a plain, grey headstone, wider than it is tall. There’s nothing witty inscribed on the stone. It looks quite ordinary except for one noticeable omission. No petunias.

“When people visit the cemetery and notice there are no flowers on her grave, they wonder why not?” said Pittman, whose local history column, Looking Backward, has run in the Neepawa Press weekly for a quarter century. “You would think there would be, for a person that important, with people coming here from all over the world” to see her headstone, and the museum in the Neepawa house where Laurence was raised.

There are 60,000 petunias in the Riverside Cemetery. So why are there none on Margaret Laurence’s grave?

No petunias are planted on the grave of Margaret Laurence. (WAYNE GLOWACKI / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS)

* * *

The Riverside Cemetery has its share of other celebrities.

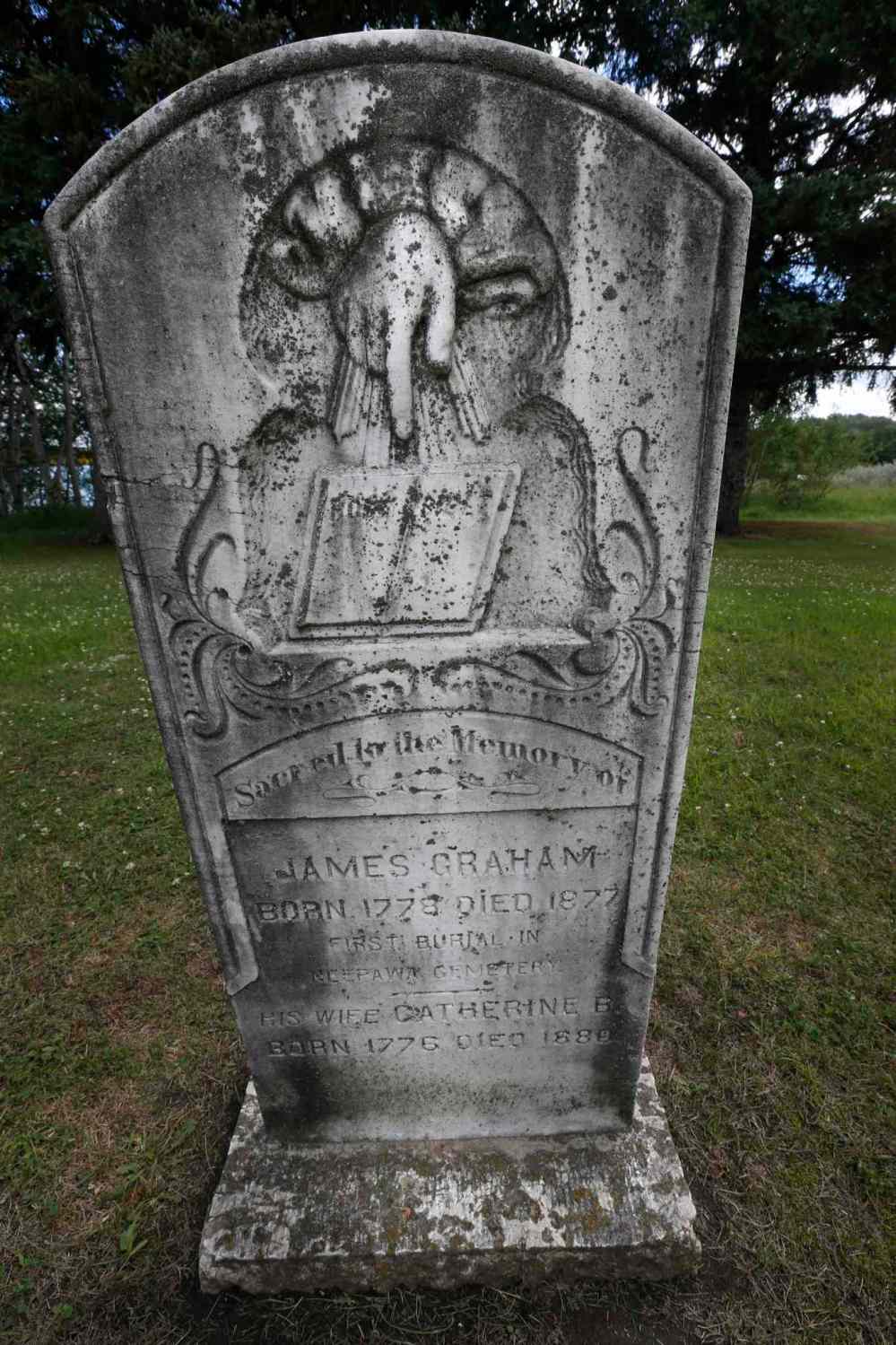

The first people to be buried in the cemetery were James and Catherine Graham. They arrived from Ontario and lived out of their covered wagon until a shelter was built.

They were either pessimists or they had a think-of-everything mentality, because they also hauled a casket with them over the rugged countryside.

They didn’t need it. James lived to be 99 (1778-1877). Catherine lived to 103 (1776-1880). That would be amazing today, almost 140 years later, but taking place before modern medicine, it borders on the miraculous. How did two people with such fabulous DNA even find each other? James’s headstone is adorned with a hand descending from the heavens pointing to a bible.

The Grahams started a trend. There are over 8,000 burials on the 25-acre site today, and room for another 2,000 graves yet. They will likely never be filled since 80 per cent of deceased now opt for cremation, Follows said.

The Graham family headstones are marked off at the eastern end where the cemetery is skirted by the Whitemud River. Across the river is the Neepawa Golf and Country Club.

The grave of George Edward Strohman, a golf enthusiast who worked at the club, overlooks the fairways. Strohman even had his putter buried with him, Pittman explained. Just as he said this we spotted a golf ball about a 20-foot putt from Strohman’s grave. Either Strohman still gets out to knock the ball around once in awhile, or someone hit a Tiger-Woods-on-steroids drive from the golf course.

The Graham and Strohman headstones are in the older section of the cemetery. The first 4,000 graves or so in the section don’t have petunias because the perpetual care policy came into affect afterwards. However, that still doesn’t explain why there are none on Margaret Laurence’s grave, since she died in 1987.

What the older section of Riverside Cemetery lacks in petunias, it makes up in tall spruce trees, smaller spruce sculpted to look like fuzzy helmets, shade, and more elaborate headstones. Many of the old headstones are ornate and look more like knights, rooks and bishops in a chess game, with a few kings and queens thrown in, like the stone angel. For all we know, they move around at night, too.

In the cemetery’s newer section, in the era of mass production, the headstones are more uniform, and look more like pawns.

The grave of Lewis Hickman, one of three brothers that died on the Titanic in 1912. (WAYNE GLOWACKI / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS)

The cemetery also has the only grave in Western Canada of a Titanic victim. It was the case of the famous switcheroo.

Leonard Hickman was to be buried there. He’d settled just north of Neepawa in the town of Eden a few years earlier. He’d returned to England to announce his engagement to an Eden woman, and bring some family members back to Manitoba with him. Leonard, his two brothers, and four male friends, all perished during their passage to Canada on the Titanic.

The body of only one of the three brothers was recovered, identified as Leonard, and shipped to Neepawa for burial.

But when Hickman’s future father-in-law, and another man who knew the family in England, looked inside the casket, they discovered an egregious error. It wasn’t Leonard Hickman but his brother Lewis.

The train carrying the casket had arrived late, and people would start arriving soon for the funeral. There was no time. So they slammed the coffin lid shut, and went ahead with the service for Leonard as planned. They announced it would be a closed-casket ceremony because they claimed the corpse was too decomposed.

A few days later, the truth leaked out. Leonard was apparently wrongly identified from a card found in his brother’s pocket. The card was from the Independent Order of Foresters in Eden, to which Leonard belonged. Lewis must have been wearing Leonard’s coat that night. He may have grabbed it in a panic when the Titanic started to sink.

The inscription on the headstone includes all three brothers. A Union Jack flies next to the grave. There’s also a bed of petunias in front of the headstone, even though they died in 1912, extended as a courtesy from the town.

Then why wasn’t a similar courtesy extended to Laurence?

Some of you have probably guessed there are no petunias on Laurence’s grave because she burned her bridges in Neepawa. Laurence wrote five novels, including Stone Angel, that took place in the fictionalized town of Manawaka, that was a thinly-disguised Neepawa.

The novels weren’t flattering to the town or residents. Many people recognized themselves in her books and weren’t happy how they were portrayed. There’s said to even be a list in town of the real names of the characters in the Manawaka series.

But if this is your guess, you would be wrong.

Despite the novels not being very complimentary in their portrayal of many residents, the town eventually welcomed her back, especially after she became famous, making Neepawa famous by extension. Her grave draws tourists to town.

The explanation for why there are no petunias on Laurence’s grave begins in her novel, Stone Angel. Flowers are a recurring motif. She has peonies planted throughout the cemetery, instead of petunias. Laurence’s protagonist, Hagar, isn’t impressed. She sees “peonies drooping sullenly over the graves.”

In Hagar’s view, the peonies are squeezing out native flowers, like wild cowslip, and she sides with the wild flowers. Domestic flowers, to her, stand for the constraints she feels in a small town, and, in the bigger picture, the stultifying rules and manners of civilized society.

Petunias are portrayed in the novel as the flowers planted in the park created by money left by her father. Hagar’s father disinherited her because he didn’t approve of her choice of husband, and left the money in his will to the town for a memorial park filled with petunias.

“Nearly circular beds of petunias proclaimed my father’s immortality in mauve and pink frilled petals. Even now, I detest petunias,” Hagar says angrily.

This never occurred to the local Margaret Laurence Committee. It wanted to correct the omission of petunias on Laurence’s grave but needed the family’s permission first. It contacted Laurence’s children, thinking their assent would be a mere formality. Committee members offered to bring the Laurence grave into the perpetual care agreement, and keep petunias on their mother’s grave.

The reply shocked them. Over their dead bodies, came the response. Anything but petunias. “Margaret Laurence hated petunias,” said Pittman.

The committee was forced to cease and desist. It has to be petunias or nothing, under terms of the perpetual care agreement.

Cemetery custodian Jack Follows trims around a grave. (WAYNE GLOWACKI / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS)

bill.redekop@freepress.mb.ca