The Timber Wolves of war

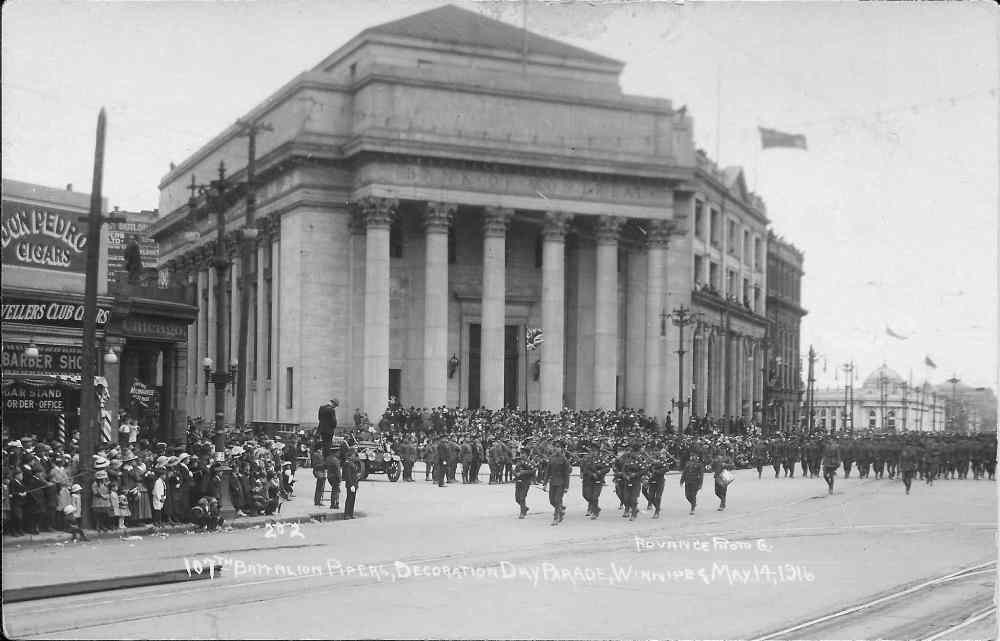

Nearly half of city-raised 107th Battalion of aboriginal descent

By: David Jón Fuller

Posted:

Last Modified:

By: David Jón Fuller

Posted:

Last Modified:

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 08/11/2014 (4136 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When the First World War erupted, many Canadians enlisted out of patriotic spirit to help Britain. But military aid to Britain was nothing new to many aboriginal people, whose ancestors had fought on the side of the British against the French, in the American Revolution, or in the War of 1812.

By the early 20th century, the government of Canada was depriving indigenous people of their lands, instituting residential schools and encouraging white settlement. Despite this, many aboriginal people enlisted to fight in the First World War. Their motives were as varied and their courage as great as their white counterparts. But those who survived the trenches found, upon their return, battlefield solidarity and commendations didn’t mean equal rights at home.

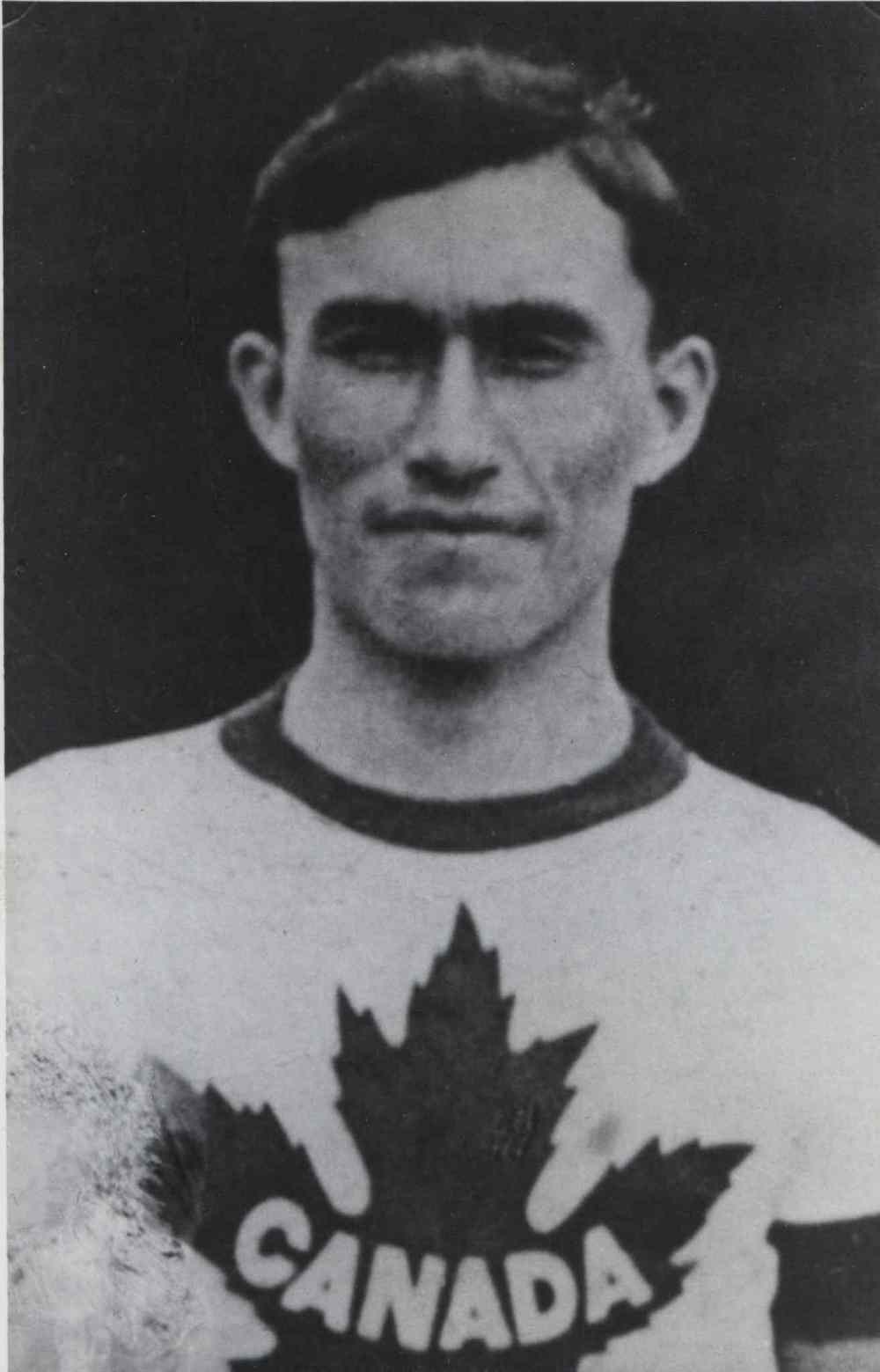

Joseph Benjamin Keeper, a Cree from Norway House and an Olympic long-distance runner, was so modest about his First World War service his son, Joe, didn’t initially know about his father’s military medals.

It wasn’t until Joe’s older brother, Stan, returned from the Second World War his father displayed his honours to accompany those of Stan.

Keeper, one of Canada’s most decorated athletes, was also a decorated soldier. He earned a Military Medal, a British War Medal and a Victory Medal. But he didn’t talk much about his wartime experience.

“I remember my father telling me one time they were wandering at night to find their way to another place,” says Joe, who was born in 1928 and later served in the Korean War. “He’d wandered over to the German lines somehow or other. Suddenly, they hear this German voice saying ‘Halt, halt!’ So they got out of there as fast as they could and as quietly as they could.”

While he didn’t talk about it much, it’s clear the Great War had a profound effect on Keeper, as it did on many other Canadians, but particularly on aboriginal people.

Joseph Benjamin Keeper was born in 1886 in Norway House. He later attended Brandon Industrial School, a residential school where he learned carpentry and showed an aptitude for long-distance running. In Winnipeg, he was encouraged to train, but the YMCA wouldn’t allow him to join, so he ended up developing his skills at the North End Amateur Athletic Club. His running ability was clear. In a well-attended 10-mile race in Winnipeg, Keeper, as a beginning runner, should have gotten a “scratch” time, or handicap, but was denied it, his son says. He won the race anyway.

“The headline said: Redskin shows clean pair of heels to 47 competitors,” Joe says.

Joseph’s athletic prowess took him all the way to the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, where he placed fourth in the 10,000-metre race. It remains the best Olympic finish by a Canadian in that event.

Keeper enlisted four years later, becoming one of the many aboriginal men in the Winnipeg-raised 107th Battalion. The battalion had one of the highest proportions of aboriginal soldiers — roughly half its number — of any battalion in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. The only other with similar numbers was the 114th Battalion, raised in Ontario.

According to Native Soldiers, Foreign Battlefields, published by Veterans Affairs Canada, roughly 4,000 Canadian aboriginal men enlisted — exact numbers are near-impossible to determine, as ethnic background was not recorded on enlistment papers. But for aboriginal recruits, the context was different.

In 1914, various parts of the Canadian government faced different pressures. Parliament had initially committed to raising a Canadian Division 25,000-men strong. At first, enlistment by white Canadians, largely of British background at the time, was sufficient. But as the war dragged on, officials had to look seriously at their policy on indigenous peoples’ enlistment — something the then-recent treaties had treated with care.

Those First Nations that had negotiated with the British Crown through the Canadian government specifically asked about miliary service and were not to be forced to fight for Canada.

However, as Timothy Winegard, a historian and author of For King and Kanata: Canadian Indians and the First World War, points out, this became almost an excuse for Ottawa to exclude all aboriginal people from joining the military.

At the time, “a lot of the aboriginal people in Canada are not treaty Indians, and when they say ‘It would violate treaties if we conscripted them,’ they don’t differentiate between treaty Indians as far as the government is concerned,” Winegard says.

The unofficial policy of exclusion began to unravel as the war continued — casualties mounted, Canada’s commitment to Great Britain stepped up, and the need for more soldiers became pressing, Winegard writes.

Meanwhile, Duncan Campbell Scott, then head of Indian Affairs, saw the war effort as a means of assimilation for aboriginal people. He was proven right, in some respects, as certain cultural prejudices and assumptions broke down in the trenches, on the side of both white and indigenous soldiers. But given the way many aboriginal soldiers were treated after the war in Canadian society and denied veterans’ pensions, it also had a galvanizing effect on the formation of independent aboriginal organizations.

In Manitoba and Saskatchewan, military service by aboriginal people was also coloured by the Northwest Rebellion in 1885.

One man who fought with the Canadian militia against Louis Riel would, roughly 30 years later, be responsible for raising the 107th Battalion by specifically seeking out aboriginal recruits.

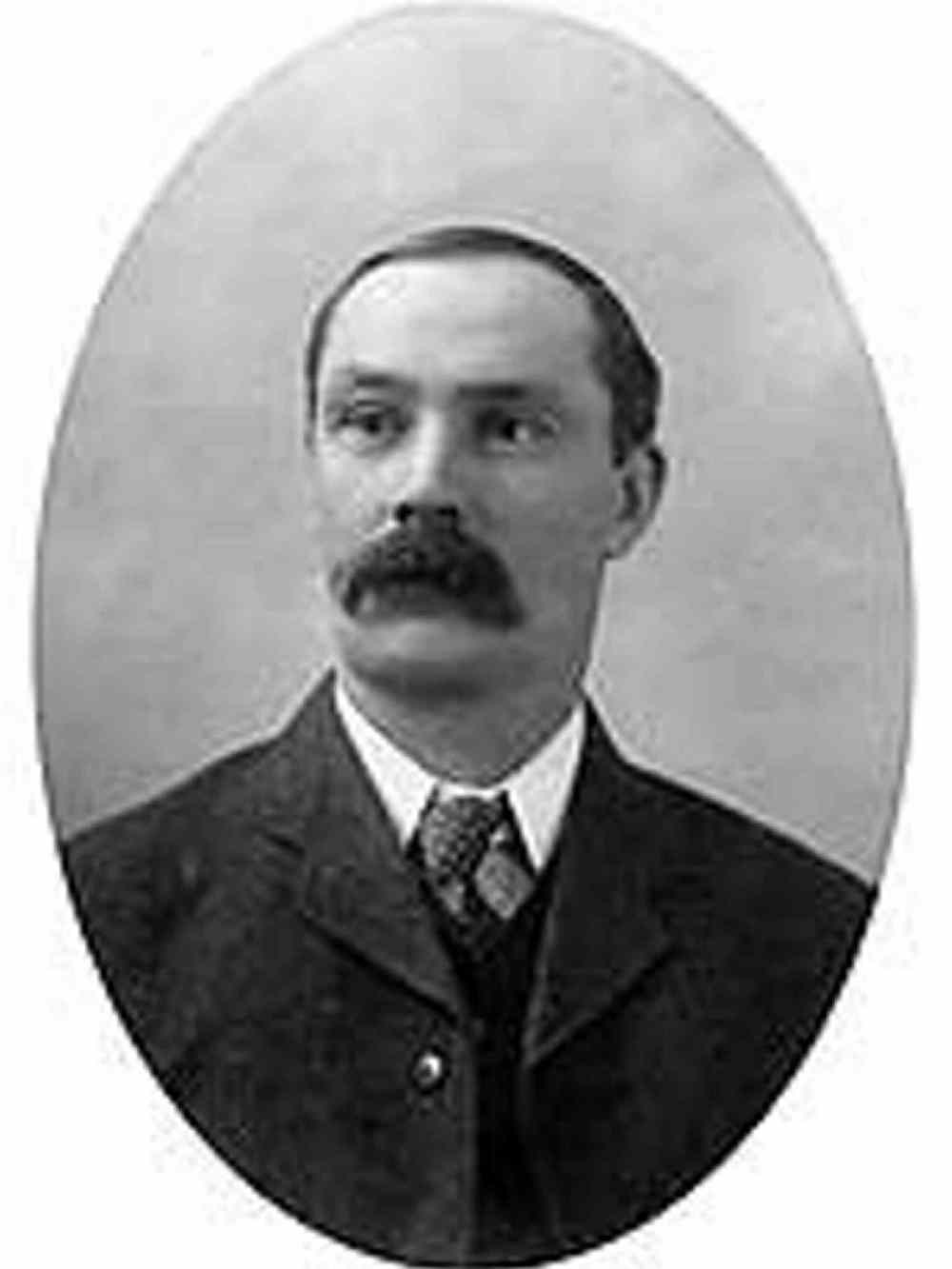

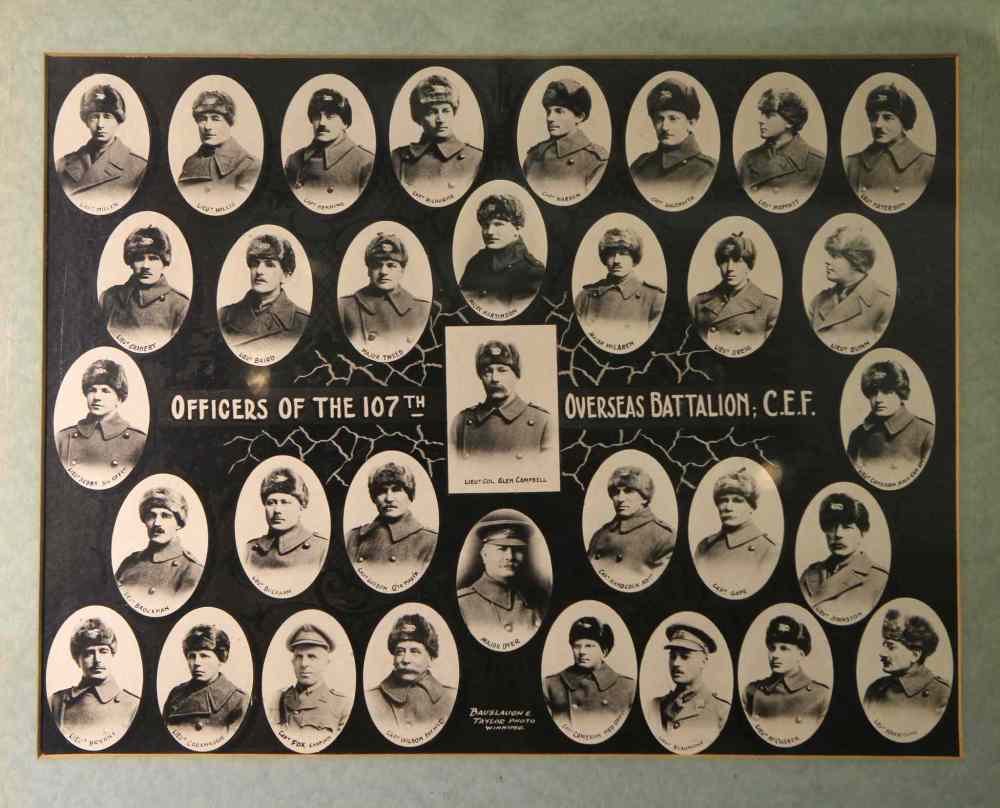

Glenlyon Archibald Campbell was born in 1863 in Fort Pelly, Sask., the son of an HBC fur trader. His childhood was spent between Scotland and Manitoba. He later lived on a ranch near Riding Mountain. In the Northwest Rebellion, Campbell served with Boulton’s Scouts, and following the Battle of Batoche, he was promoted to captain.

Campbell, who also served as MLA for Gilbert Plains and later MP for Dauphin, made his living by hunting, trapping and ranching. His first wife, Harriet, was Ojibwa and daughter of Chief Keeseekoowenin. He was fluent in Ojibwa and Cree. “He basically himself became native for the most part… he assimilated into the native population and hunted and trapped and lived that lifestyle,” Winegard says.

When the Canadian government decided to actively encourage indigenous people to enlist in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in 1915, Campbell was in a unique position.

“He saw the value in native soldiers, based on his pre-war livelihood of hunting and trapping,” Winegard says.

Campbell pushed for their recruitment and, unusually for a man in his 50s who had not seen active service for decades, was granted permission to raise a battalion. He began recruiting in November 1915, attracting volunteers from Manitoba and beyond and achieved full strength (roughly 1,000 officers and other ranks) within three months, about 500 of whom were aboriginal. Campbell’s own son, Jack Campbell, also joined the 107th.

Among the unit’s aboriginal soldiers were men of the Blackfoot Confederacy, Cree, Ojibwa, Iroquois, Sioux, Delaware and Mi’kmaq. Winegard said many did not speak English, and Campbell often conducted training and daily matters in Cree and Ojibwa. English instruction was provided to the soldiers.

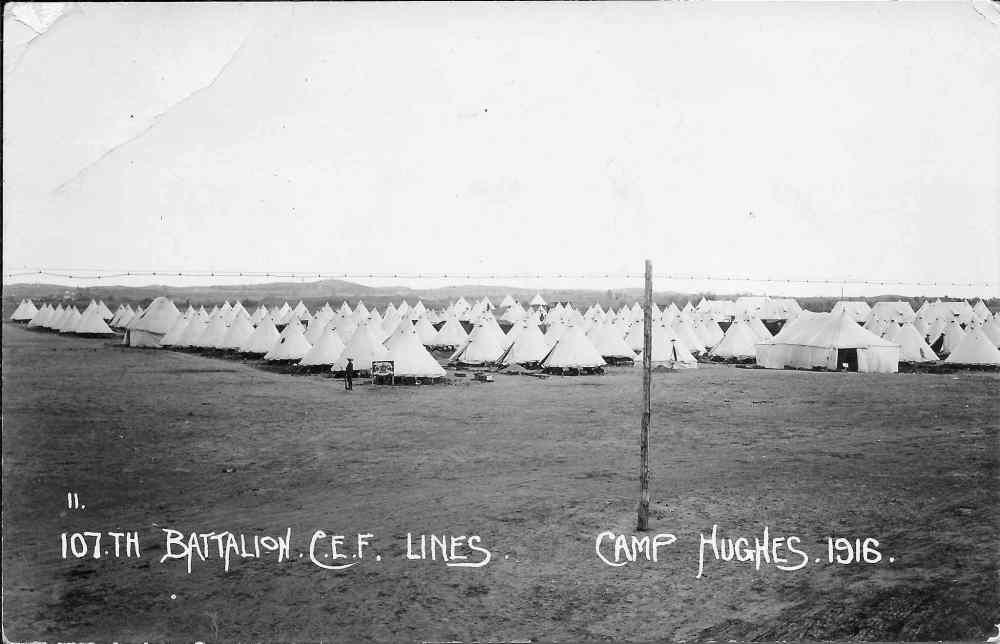

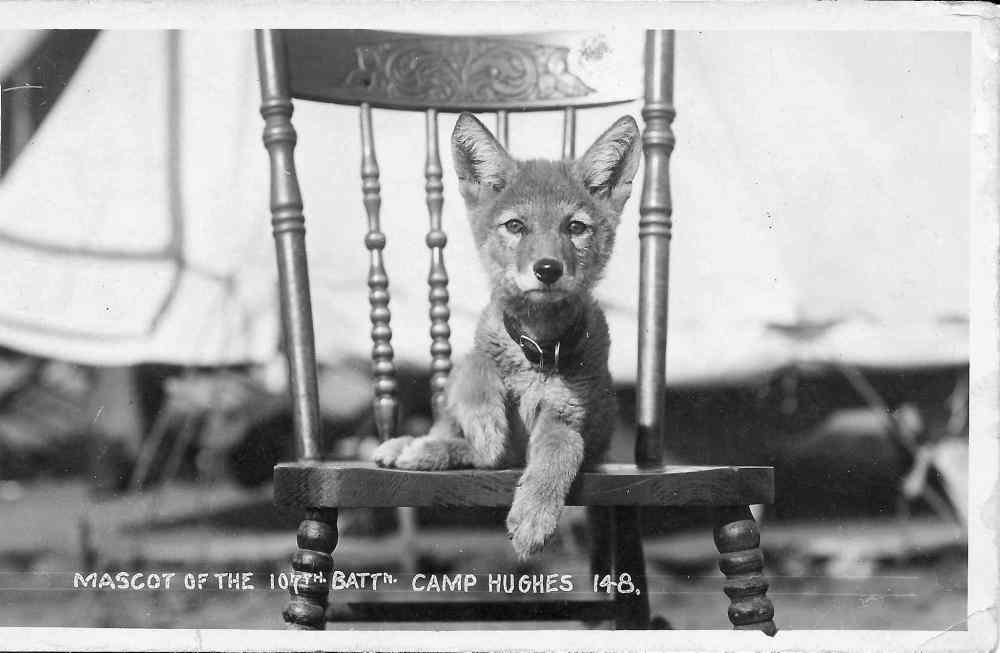

Training was conducted at Camp Hughes in western Manitoba. Following training, the unit shipped overseas on Sept. 19, 1916.

There were other units in which aboriginal people from Manitoba enlisted, such as the 108th Battalion, which was raised in Selkirk. Many recruits came from Peguis First Nation.

Selkirk’s Bill Shead, a Cree member of the Peguis band and military historian, suggests the service of recruits from Peguis compared to peacekeeping.

He points to a tradition from the time of Chief Peguis and his descendants in not only helping the Selkirk settlers in what is now Winnipeg, but also protecting them when they were intimidated by fur traders. Peguis also sought to ease tensions between rivals in the fur trade. Later, the band chose to remain neutral in the Riel Rebellion, despite many appeals from Riel for their support.

A number of Shead’s relatives served in the First World War. He served in the Royal Canadian Navy from 1956 to 1992, was the prairie regional director general of Veterans Affairs Canada from 1986 to 1992, and worked with Chief Jim Bear of Brokenhead First Nation to repatriate the medals of Sgt. Tommy Prince.

Meanwhile, many Métis enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. According to the Manitoba newspaper La Parole in 1916, “30 descendants of Métis who fought at the side of Louis Riel in 1869-70… have just enlisted at Qu’Appelle. They are all members of the Society of French-Canadian Métis of that place. Their names are inscribed on the (society’s) roll of honour.”

A nephew of Riel, Louis Philippe Riel, was regarded as one of Canada’s best snipers during the war.

Shead says service by soldiers from St. Peter’s (Peguis First Nation’s original homestead), extended to overseas even before the First World War.

“One of the lesser-known stories is the story of the Nile River boatmen who went with Wolseley up the Nile River in 1885 to relieve Khartoum,” Shead says. The graves of at least three boatmen can be found at the Old Stone Church just north of Selkirk.

Shead says there is an interesting back story to the Peguis recruits enlisting.

“In 1907, the St. Peters land was surrendered illegally. There was a court case; the government of Canada lost the case, but they passed a bill called the St. Peters Act in 1914, which made the surrender legal. And anyway, the people of St. Peters were relocated to what is now Peguis and they re-established their community there starting in the years from about 1909 onwards. So most of these people we’re talking about who served in the First World War from Peguis and St. Peters were just coming out of this catharsis of the surrender.

“The interesting thing about the 108th Battalion was the fellow who raised that battalion was George Bradbury.

(He) was the MP just after the surrender and he argued in the House of Commons against the government against the surrender of St. Peters.”

Like the 108th, the 107th was to be broken up upon arrival in England. But Lt.-Col. Campbell tried to keep his men together, particularly the aboriginal soldiers, in essence to watch over them.

“Glen Campbell actually said he thought they’d be treated poorly if they were in other units so he was trying to collect them all to his unit because he knew the culture,” says Winegard. “He knew how to deal with them and basically said, ‘They need to be under me because racism might happen in other units, but under me they’re going to get better treatment than they would in any other unit.’ ”

On Oct. 12, 1916, Campbell wrote from Witley Camp in Surrey, England: “Referring to the honour you ceded to me to let my battalion volunteer as a construction unit in preference to being drafted in small sections. I have had a conference of my officers, and they have unanimously decided with me to offer our services as a construction battalion for immediate service. In this respect I would like to point out that many of our men and officers are qualified for such work as might be allotted to a battalion of this nature, and I trust that our offer will receive favourable consideration.”

By designating the 107th a pioneer battalion, in which soldiers carried out not only engineering tasks but also those of regular infantry, Campbell was able to keep a large number of his men together, and the 107th persisted. As his great-grandson, Glen Campbell, said recently: “He would do anything for his men. Married to the daughter of Chief Keeseekoowenin, he had great respect for Canada’s First Nations people, which he inherited from his father, HBC chief factor Robert Campbell. And (he felt) that given the chance, First Nations soldiers could be just as good as any soldiers. And they proved Glen was right.”

The 107th was never an all-aboriginal unit, and whatever misconceptions or assumptions the white and aboriginal soldiers may have had about each other in the beginning, the shared experiences of the war broke down boundaries, Winegard says. The soldiers treated each other as equals.

Joe Keeper says of his own experience in the Armed Forces and serving in the Korean War, “there was recognition, you know, but there was never prejudice. There was incipient racism that still exists all over the place, but the way I’ve always felt about it is people who are like that, they are a product of their own culture. But I never looked for it. All my life, I figure, well, if people are worried whether I’m Indian or not — that’s their problem.”

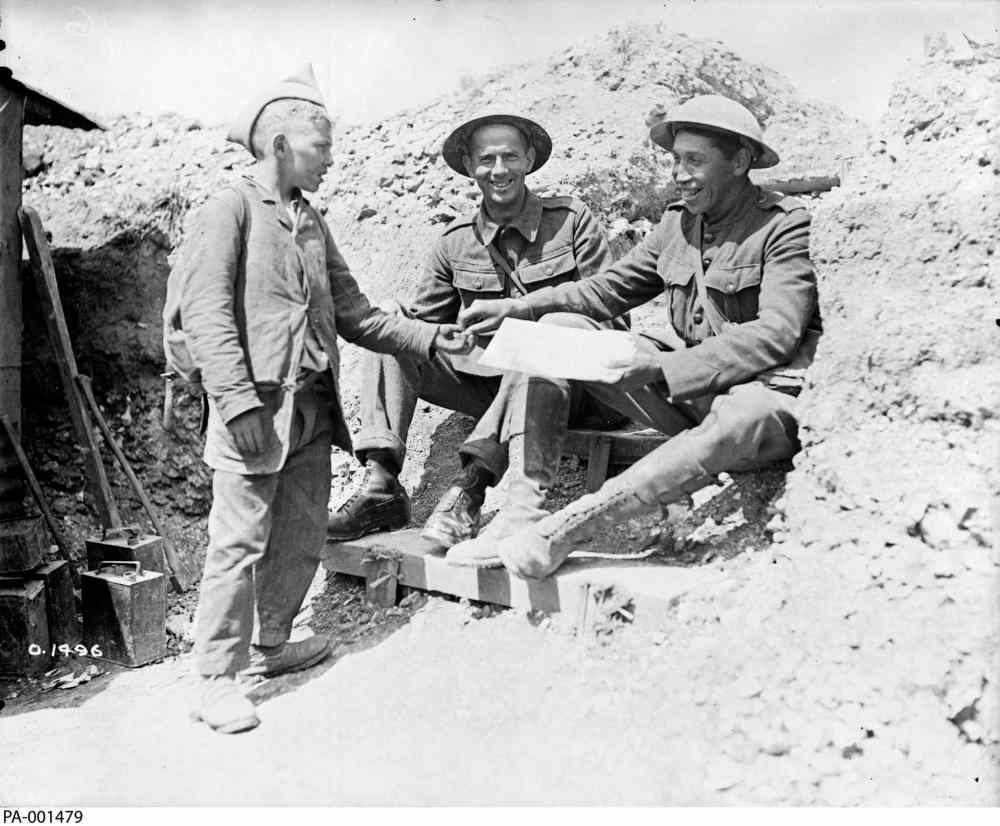

Winegard also says some cultural differences may have benefited the white soldiers. In contrast to a British mentality in which stress and anxiety were to be kept a tight lid on, he says the aboriginal soldiers exemplified a more community-based approach.

Shell shock, now referred to as post-traumatic stress disorder, was then often called “cowardice” by those in command. Winegard says the aboriginal soldiers’ use of humour and community-based approach to healing to cope with the tension of life at the front helped not only them but also the other soldiers, and they were well-loved for it.

Shead observes that at that time, Canada and Manitoba felt a strong influence from British culture. “In fact we were all known until 1947 as British subjects, not Canadian citizens, and that stoic (outlook), or ‘stiff upper lip’ or whatever you want to call it, a British attitude, was predominant; but if you looked at it from the point of view of somebody who was not that immersed in British tradition or the British way, and you’re more attuned to your own culture — that sense of humour predominates. And I’m not just talking about aboriginal people. I think it’s indigenous to most people, having a sense of humour, particularly in a difficult time.”

He adds: “If you were suffering from shell shock or post-traumatic stress (disorder) it’s largely because you haven’t been able to find a way to release it. And if you had a sense of humour and you were able to release it, that’s good.”

Among the places the 107th served were Arras, Vimy Ridge, Cambrai, Hill 70, Ypres and Passchendaele.

Casualties were high for Canada, whether in battle or as a hazard of battlefield conditions. Being exposed to gas attacks could develop into outbreaks of tuberculosis, which has generally taken a greater toll among aboriginal people.

Accidents also took lives, such as that of Pte. Kenneth McClure Asham of St. Peters, who enlisted in the 108th Battalion and later served in the 78th Battalion. Asham, Shead’s great-uncle, died in late March 1917. “He was sent as a reinforcement to the 78th Battalion and he was actually killed in a bombing accident a few days before the battle of Vimy Ridge,” Shead says.

He suspects the bomb was a Mills bomb, which was a kind of early grenade.

The event is recorded tersely in the war diary for Asham’s unit for March 28: “Weather fair — Bombing accident — 1 officer Lieut. Hull and 5 other ranks wounded 1 other rank seriously.”

One diversion for soldiers came through sporting events. And aboriginal athletes such as Keeper and Tom Longboat did their units proud. Longboat, winner of the 1907 Boston Marathon and a Canadian athlete at the 1908 Olympics, had a friendly rivalry with Keeper, Joe Keeper says.

“He beat him (Longboat) a couple of times; but he’d say, ‘If you let him get ahead of you, you couldn’t catch him.’”

In 1917, Keeper and Longboat, both of whom were dispatch runners for the 107th, won an inter-Allied cross-country championship near Vimy Ridge. As Winegard writes in For King and Kanata, these accomplishments were highlighted in the battalion’s routine orders at Campbell’s insistence.

Campbell himself was not immune to the pressure and dangers of the front. After victories at Vimy Ridge and Hill 70 outside the town of Lens, he died of kidney failure on Oct. 20, 1917.

The 107th remained together until 1918, when the entire Canadian Expeditionary Force was reorganized ahead of a major push on the Western Front. The battalion was disbanded and absorbed into the 1st, 2nd and 3rd Canadian Engineer battalions on May 28, 1918.

While aboriginal soldiers had been treated as equals in the trenches, the old racist boundaries were still in place when they returned home.

“They didn’t get any of the benefits of the Soldier Settlement Act,” says Winegard, adding the words of Arthur Meighen in 1917, then superintendent general of Indian Affairs, were “brilliant and horrific.”

Meighen wrote: “It is an inspiring fact that these descendants of the aboriginal inhabitants of a continent so recently appropriated by our own ancestors should voluntarily sacrifice their lives on European battlefields, side by side with men of our own race, for the preservation of the ideals of our civilization, and their staunch devotion forms an eloquent tribute to the beneficent character of British rule over a native people.”

Yet, the aboriginal soldiers’ sacrifices in the war didn’t change anything, Winegard says.

“It was ‘Thanks for your service, you’re no longer needed, now go back to your reserve, shut up and be a good Indian.’ And there was confusion, too, between Veterans Affairs and Indian Affairs over who was supposed to take care of these guys, because that costs money, and nobody wants to pony up the money. So Veterans Affairs says it’s Indian Affairs’ responsibility under the Indian Act; Indian Affairs is saying, ‘No, no, it’s your responsibility because they’re active soldiers.’ So this just goes on until they both say, ‘Well, let’s just forget about it.’ Because nobody wants to pony up the money.”

Joe Keeper says his father felt that change in attitude, one that was significant for many aboriginal veterans.

“One of the things that he did, he was a treaty, a status Indian; but when he came back from overseas, he wanted to work on a farm and he thought he would like to settle. He’d like to get off the reserve and maybe get some land in the Interlake. And he applied for it but he was told because he was a treaty Indian he couldn’t get it — he wasn’t allowed. So he said that was one of the reasons he got out of treaty.”

Joe adds: “The other thing that he mentioned, he said it one time, is that he had a particular attitude when he went into the army of not being as good as the white man. But he saw when he went into the army, he was no different, he was as good as any man. And when he came back and then he was treated by Indian agents as a lesser being, he didn’t want to follow that, he didn’t want to have to deal with Indian agents anymore.”

Keeper wasn’t alone. After both world wars, there was a desire among aboriginal people to organize themselves. That spawned a pan-aboriginal organization called the League of Indians of Canada. Winegard writes that while the league splintered into smaller political organizations, it set the precedent for later organizations. The Assembly of First Nations was one of those.

The crucible of the Western Front may have drawn the inequalities at home in sharp relief. As Joe says, “I do remember my father talking about Tommy Longboat. He said he remembered him being a sort of social activist. He remembered him, when they were in the dugout, Tommy would hit the table and say: ‘What we need is freedom!’”

David Jón Fuller is a Winnipeg Free Press copy editor and the author of two short stories featuring the 107th Battalion, in Long Hidden: Speculative Fiction From the Margins of History and Kneeling in the Silver Light: Stories From the Great War.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.