Generation Rx: Waking the giants

Runaway success story couldn't outrun Big Pharma, FDA

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/04/2013 (4636 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

If any Internet pharmacist were going to run into trouble with U.S. authorities, most people would have picked Daren Jorgenson.

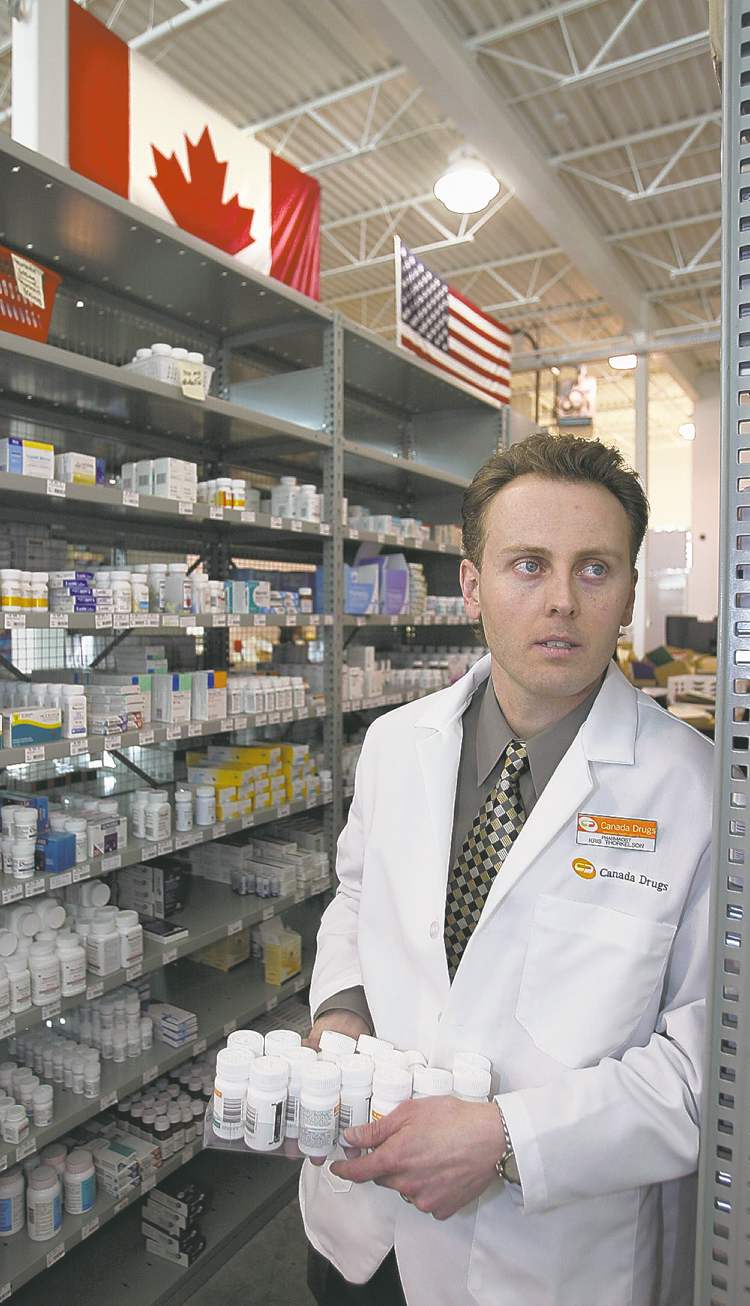

Kris Thorkelson, now part of an investigation into how counterfeit cancer-treatment drug Avastin infiltrated the United States, was the “white hat” of the industry.

While others partied and blew their money on sports cars and private jets to Las Vegas, Thorkelson would go home at night and be a father. Even with an investigation hanging over him, people who know Thorkelson have nothing but complimentary things to say. They describe him as quiet, efficient, trustworthy and likeable — all qualities you want to see in your pharmacist. He is also described by one industry player as “ruthless” when it comes to business. His Internet pharmacy would become the biggest in Canada.

Jorgenson, on the other hand, can be a brash, frustrating, say-whatever’s-on-his-mind agitator — and that may be putting it politely.

Andrew Strempler, the maverick young entrepreneur who started the first large-scale Internet pharmacy, is now serving time in a Georgia prison for mail fraud.

In addition to his Internet pharmacy business, Jorgenson has had other controversial business ventures. He initially disappointed fans of the Royal Albert Hotel music scene by closing it after his purchase, but relaunched it recently. He left some bad feelings when he closed his hair salon business, the Vault, although Jorgenson maintains all staff got paid. He’s had numerous clashes with government concerning his medical centres and his Albert Street real estate.

Then again, Jorgenson’s background is different from those of most pharmacists. His parents married when they were 16 after his mom became pregnant with his older brother. His parents were 18 when they had Daren. The family bounced around public housing in Saskatoon and Edmonton.

“I didn’t grow up poor but I grew up blue-collar,” he said. When Daren graduated from the faculty of pharmacy at the University of Manitoba, he was only the second person in his extended family to obtain a university degree.

“I don’t look like a typical pharmacist. Everyone thought I looked crooked, that I would be the one who would end up in jail,” said Jorgenson.

Despite his reputation and shaved-head wrestler look, Jorgenson is surprisingly gentle-voiced in person. He chose to meet at the café in the Yale Hotel, a gritty Main Street hotel and bar built in 1906 that’s almost next door to Jorgenson’s Four Rivers Medical Clinic. He’s had businesses nearby for 15 years, including his former online pharmacy, Canadameds.com.

Jorgenson got his start in the online-pharmacy business by dumb luck, he said. He knew a physician everyone called the “Love Boat Doctor” who would ride free on cruise ships in exchange for serving as ship physician. The doctor mentioned how every time the ship stopped at a Caribbean port, Americans would get off and load up on all the prescription medicine they could carry. Jorgenson checked the price difference between Canadian and American drugs and understood why. One of those people whose brain is always brimming with ideas for new businesses, Jorgenson started advertising mail-order prescriptions via the relatively new communication technology called the Internet. That was in about 2000.

He and three employees opened a storefront pharmacy and online pharmacy called Canadameds.com at 885 Main St., near Euclid Avenue. But they were only filling maybe 10 online orders a day to the United States. Strempler’s online pharmacy MediPlan in Minnedosa was growing much faster. Then NBC Nightly News came to Winnipeg and did a story on Canadameds.com.

“The next morning (after it aired) we came into work and we had like 4,000 (orders for prescriptions drugs) that had arrived overnight. We didn’t know what to do,” said one former employee. Jorgenson had just one phone and one fax machine. Now the phone was ringing off the hook and the fax machine was overheating. Someone ran out and bought three more fax machines. Orders clacked away 24-7. A measure of their new-found success was they had to keep replacing fax machines because the motors would burn out.

The bigger problem was staffing. Recalled Jorgenson: “We were like, ‘Oh My God!’ It was exciting but also scary. The biggest task was you’d come in the morning and say, How can we get more people working here? Who has friends, family or cousins? Because you had to hire so fast. I’m sure MediPlan had the exact same problem or more so,” said Jorgenson.

“We’d go in Monday morning, and go home Tuesday night. Go in Wednesday morning, go home Thursday night. We’d sleep every second night,” said Jorgenson. “You had to. There was no other way of doing it. Not for the whole time but for a good six months.”

Ron Guse, the registrar of the Manitoba Pharmaceutical Association, would show up regularly. He was a kind of Inspector Jalvert out of Les Miserables in his indefatigable pursuit of regulatory issues with Jorgenson and other Internet pharmacists.

Actually, the Internet pharmacists called him the Sheriff of Nottingham (and they, by extension, were Robin Hood and his merry men benefiting the poor — and themselves).

Jorgenson said Guse launched about 20 complaints against him but a committee of pharmacist peers deemed none worthy of disciplinary action. Guse wouldn’t comment on Jorgenson’s claim. Of his relations with online pharmacies, Guse would only say, “We didn’t see eye to eye on some of the things around safety and ethical.

“One of (the online drug industry’s) comments was that we were trying to shut them down,” said Guse. “We never made that comment. We tried to make (the industry) legal and ethical.”

But Canadameds.com was growing so fast back then, Guse did catch Jorgenson on one infraction: too many personnel per square foot. Canadameds.com was running out of room. Jorgenson was given seven days to get more space.

“So we went into Bargain World next door and told them we’d buy the building and everything in it if they moved right now,” recalled Jorgenson. The owners were stunned, but it was an offer they couldn’t refuse. “Then we brought in plumbers, electricians, computer guys and transformed it into our pharmacy in seven days.”

Jorgenson was swamped with money, too. “It’s hard to handle it. I was screwed up, too (like some of the other Internet pharmacists who became rich fast). So much money is coming at you all the time. All of a sudden, so many people want to talk to you, work for you, work with you. It messes you up.”

George Orwell liked to say rich people are just poor people with money, and online pharmacists seemed to bear that out with their spending binges. It wasn’t just Strempler from MediPlan who was spending lavishly, although he may have been an extreme case. Other pharmacists were also buying sports cars, mansions, chartering private jets and heli-skiing off mountaintops in the Rockies.

Jorgenson also chartered private planes to Las Vegas. It isn’t as hedonistic as it sounds, he said. Several times, he took a child with cancer and the mother along to see a music act in Vegas.

“I didn’t blow my money like some people. Still, you can’t help but be blowing it.”

He bought David Asper’s house on Wellington Crescent, right next-door to Leonard Asper’s house, which had been purchased by Strempler. Everyone in the industry knew Jorgenson and Strempler didn’t get along, and Jorgenson admits as much, yet he still bought the house next-door. Jorgenson also owned a house in Banff and would fly back and forth every week. The house in Banff coincided with a second Internet pharmacy he opened in Calgary that employed 200 people.

Like other Internet pharmacists, he’s reluctant to quantify financial returns. He did, however, allow that at its peak, the Calgary online pharmacy, called Total Pharm Care, which Jorgenson owned with three partners, was paying out a $100,000 dividend to each partner every two weeks. Per partner, that’s $2.6 million in a year. “We didn’t want money in the company for drug companies to sue and get hold of,” Jorgenson said.

They were crazy times. It was dumb luck to be in the industry but it also took nerve for Strempler, Jorgenson and Thorkelson to become the three biggest players.

“I was just trying to stay alive day to day… Everyone’s trying to shut you down,” said Jorgenson. “MPhA (the Manitoba Pharmaceutical Association) is trying to take away your licence every day. So they’re threatening. U.S. Customs is sending you letters saying you can’t do it. You have to have the (fortitude) to say, ‘OK, I’m still going to do it.’ “

The Food and Drug Administration in the U.S., and the Manitoba College of Physicians and Surgeons, with its threats to suspend doctors who co-signed prescriptions, were also trying to thwart online pharmacists.

But Jorgenson had an idea for dealing with that. Instead of working in the dark and competing against other pharmacists, he would do the opposite. He would help other pharmacists get into the industry, loaning out his staff to show other pharmacies how to set up online operations.

The more people involved, the more it would legitimize the industry, he reasoned. Ultimately, that would give the industry more political clout.

This move by Jorgenson propelled Manitoba into being the industry leader. At its peak in the mid-2000s, Manitoba, with about three per cent of Canada’s population, made up 75 per cent of the Internet pharmacy business in Canada. Jorgenson also launched the Canadian International Pharmacy Association as a vehicle to promote and self-regulate pharmacies.

“Smart businessman,” is how one former online pharmacist described Jorgenson. Another industry insider, who had many dealings with Jorgenson, said of him: “He was the most enterprising of all of them. Daren excelled of the three. He was always looking for expansion and growth opportunities.”

More than half a dozen people spoke to the Free Press on the condition of anonymity. These individuals were either once Internet pharmacists or worked with Internet pharmacists. Their reasons for not being identified included the sensitivity of their information, the controversial nature of the business or simply having moved on to other occupations.

Jorgenson’s next feat would be to suss out a model for procuring product internationally. When drug manufacturers began cutting off supplies to known Internet pharmacies, the pharmacies looked abroad to source prescription drugs. Jorgenson led the way, becoming the first to set up overseas.

He opened pharmacies abroad, including Heathrow Pharmacy near Heathrow Airport in London, or partnered in pharmacies such as MagdenDavidMeds near Tel Aviv. (One of the four partners in MagenDavidMeds was former Winnipegger Nathan Jacobson, who pleaded guilty in 2008 to dispensing drugs to Americans without legal prescriptions and laundering $46 million in drug payments, through a company called Affpower.)

Jorgenson’s drug-procurement model was very simple versus those that followed. Customers could go to his Canadameds.com website and order directly from these pharmacies. They could go online, compare prices between MagdenDavidMeds or Heathrow Pharmacy or other pharmacies Jorgenson set up. For example, the price of Lipitor in Australia was half that in the U.S., and Jorgenson had an office there, too. Drug purchases arrived within two to three weeks.

But most other online pharmacists, including Strempler, didn’t follow Jorgenson’s example. They opted for transshipping instead. Under this model, the online pharmacy procures drugs overseas, has them shipped to a jurisdiction with weak oversight such as Bahamas, and has the prescriptions filled there. The drugs are then shipped to American patients.

Jorgenson didn’t agree with the model, arguing it wasn’t safe. He was buying his drugs from Western nations with similar standards to North America. Other players were procuring many of their drugs at much lower prices from developing countries. Canadian online pharmacies would buy drugs from countries such as Turkey at deeper discounts and offer it to American customers at lower prices than Jorgenson could offer. It made it hard for him to compete.

Jorgenson objected, quit the CIPA board, then quit the industry completely. He sold his online pharmacies in 2006 and the return wasn’t anything what it might have been had he sold a year or two earlier.

“I didn’t really walk away with piles of money,” he said.

Not that he’s poor today. As one insider said, Jorgenson is someone who has made a lot of money and lost a lot of money. He still lives on Wellington Crescent. He owns the Four Rivers Medical Clinic, with locations on Main Street and on Broadway. The Broadway clinic has a Rise and Shine Clinic so people can see a physician before they go to work, another one of Jorgenson’s innovative ideas. His Main Street clinic has offered physician house calls for 15 years, employing up to six doctors at a time.

— — —

It was getting too hot in the kitchen for many online pharmacists. The rising Canadian dollar, the complexity of accessing prescription drugs offshore, new Medicare legislation in the U.S. and pressure from regulatory agencies and Big Pharma launched an exodus of Internet pharmacists.

While others were fleeing, Canada Drugs Ltd.’s Thorkelson viewed it as a buying opportunity. He scooped up other companies’ patient lists to do the future refills.

“Kris kept his chips on the table and got bigger whereas others started taking their chips off the table,” said Jorgenson. “So many people exited the industry. Kris is kind of the lone man standing.”

Thorkelson grew up on a family farm near Riverton in Manitoba’s Interlake. He and Jorgenson both graduated in 1991 with pharmacy degrees from the University of Manitoba. In 1993, they scraped together $7,500 each to buy a pharmacy at 406 McGregor Ave. in the North End.

Sometime around 2001, after ending their partnership but still keeping in touch, Thorkelson asked Jorgenson about the Internet pharmacy business and Jorgenson gave him his start. Jorgenson says he provided Thorkelson his first database of prescription-drug prices so he could calculate the markups. He also gave him a website and a doctor who could co-sign prescriptions.

Thorkelson’s nickname became “the Viking” among other Internet pharmacists because of his Icelandic heritage. “Kris was very quiet, brilliant. He came across as sort of a meek personality but he was still ruthless in his business tactics,” said someone who had frequent dealings with him.

While an estimated 150 pharmacies once dabbled in online sales in Manitoba, the sector very quickly boiled down to one company: Thorkelson’s. His control was made even more complete with his accumulation of website domains — more than 3,700 of them. Their names range from laughers such as CheapoDrugs.com to an ad infinitum list of the mundane, including Pricemartpharmacy.com, Usapharmacyservices.com and Smartmed.ca. The object of having so many domains is they directed all web traffic for online prescription drugs to one company: Canadadrugs.com.

Thorkelson’s Canada Drugs plant in St. Boniface, off Dugald Road, employs nearly 500 people. His net worth has been pegged at several hundred million dollars and he is said to own a stable of apartment buildings in Winnipeg.

A staff member at Canada Drugs, speaking on the condition of anonymity, said Thorkelson is a popular boss. Staff are well-treated and the company allows job flexibility. Thorkelson holds monthly luncheons with staff for anyone with a birthday that month. The luncheons are specially catered. He’s very much around the operations all the time, the employee said.

“He’s a great guy. He’s got a good heart. This is his baby. He started with a mom-and-pop pharmacy, got into online pharmacy and it exploded. It helps a lot of people every day,” the employee said.

Thorkelson hasn’t granted a media interview in years, and he declined a request from this newspaper, but his operation mirrored others in the earlier years of Internet pharmacy. Where Thorkelson deviated is by going beyond just selling drugs to individual patients. In about 2009, he got into the wholesale trade, selling in bulk to medical clinics, cancer clinics and cosmetics clinics. This was new territory for an Internet pharmacist, and one that was potentially much more lucrative. But it was also less reliable, as Thorkelson was to find out.

The shipments of counterfeit Avastin into the United States surfaced publicly in early 2012. Avastin, a chemotherapy drug used to treat colon, lung and kidney cancer, is made by Roche Holding AG of Switzerland. The counterfeit Avastin, which contained no active ingredients, was delivered to at least 20 American cancer clinics.

The FDA traced the shipments to a company called Montana Health Care Solutions in Belgrade, Mont. It was selling counterfeit Avastin to American doctors for $1,995 per 400-mg vial, about $400 less than the regular price.

Immediately following the discovery, federal prosecutors in Montana seized $1 million, 11 parcels of land and a 2011 Aston Martin sports car from Paul Bottomley, who worked under contract to Montana Health, the Wall Street Journal reported. Prosecutors allege Bottomley illegally profited from marketing foreign medicines, including the fake Avastin, to American doctors.

The FDA kept pulling on the thread and it led to Tom Haughton, Thorkelson’s brother-in-law, who is based in Barbados, and Thorkelson’s Canada Drugs in St. Boniface. Staff members at Canada Drugs have admitted to the Free Press and other media the fake Avastin came from a Canada Drugs company.

Thorkelson has not been charged with any criminal wrongdoing. He is part of the ongoing investigation into the fake Avastin.

People familiar with Thorkelson’s operations said he has three main distribution points: Winnipeg, Barbados and Nottingham, England.

Winnipeg is largely a call centre and administrative headquarters for Canada Drugs, but also handles a small portion of mail-order shipments to the U.S. — perhaps 10 per cent of the company’s total. The trade is small because transshipping — where drugs are sourced from abroad into one location for re-shipment elsewhere — is illegal in Canada. Any drug shipped out of Winnipeg has to be sourced within Canada.

The busier distribution centre is in Barbados, a free-trade zone. It receives shipments from around the world and fills individual prescriptions for mail-order delivery to the U.S. In 2011, the Barbados operation employed 130 people, according to the Wall Street Journal.

The other distribution centre — River East Supplies Ltd. in Nottingham, England — handles the wholesale trade, shipping drugs to American doctors, hospitals and health clinics.

The counterfeit Avastin was shipped to the U.S. by River East Supplies. Tom Haughton, based in Barbados, ran both the Barbados and Nottingham distribution centres.

A primary source of drugs for Canada Drugs was the European Union’s parallel trade, which allows countries in Western Europe — primarily Britain, France and Spain — to take advantage of price differences in Eastern Europe. Essentially, pharmacies buy cheaper product from Eastern European countries, where drug prices are discounted to reflect lower incomes. The drugs can then be legally relabelled, repackaged and resold for shipment to American customers.

However, the parallel trade has limited supplies for Internet pharmacists to access. In order to supply more quantities for the wholesale trade, Thorkelson had to move farther afield sourcing drugs from places such as Turkey and India.

Drugs were shipped to Nottingham, where they were relabelled in English and then reshipped as bulk wholesale to a location such as Montana Health Care Solutions.

As one insider said, getting the bulk product into the U.S. is the toughest part. But once it’s in a U.S. warehouse, it looks like part of the regular wholesale trade.

The Wall Street Journal traced the shipment of fake Avastin to a name on the invoice, that of a Turkish drug company called Kirbac Medikal. When a WJS reporter went to the Istanbul address of Kirbac Medikal, it found a textiles warehouse. No one there had ever heard of the company.

Thorkelson responded at once when alerted about the counterfeit product. Cancer clinics were notified and shipments were immediately stopped. The counterfeit Avastin is believed to have been used by just two patients and they were not harmed as the contents were benign. Thorkelson moved quickly to provide legitimate drug supplies to those patients free of charge.

Thorkelson has since stopped sourcing drugs from both Turkey and India, a Canada Drugs employee said. The company is now only sourcing from the United Kingdom (including parallel trade), Australia and Canada. “It eliminates all the risk that anyone could be getting any bad product ever again” although it costs more, the employee maintained.

Thorkelson also got out of the wholesale business. About 20 people were laid off at the St. Boniface plant earlier this year and more layoffs are expected. Severance pay has been generous, however.

Two things undermined wholesale trade. First, it forced Thorkelson to tap into more distant sources because there wasn’t enough product in parallel trade. That made him reliant on places where there was less regulatory oversight.

Second, you can’t crack open a wholesale shipment for inspections — such a move means it can no longer be sold for wholesale. With the mail-order business, you have to break open the shipments to fill out individual prescriptions, and at that time you can do random testing.

The infiltration of a counterfeit cancer drug into the U.S. is being treated very seriously. There have long been fears terrorists could try to strike by contaminating the drug supply. Having the American drug network breached, and by a company allegedly controlled by an Internet pharmacy, is an embarrassment and gives credence to those fears. Ultimately, this is seen as a national security issue and regulatory changes are expected.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration is circling Canada Drugs. The Globe and Mail reported the FDA has subpoenaed several doctors in the U.S. for information about Canada Drugs. Jorgenson believes U.S. doctors are being threatened with jail and loss of licence in exchange for testimony. “They’re prosecuting all these little people in the chain, and then when they come to the big whale, Kris, they’re going to have like 100 doctors” testifying against him, said Jorgenson.

Should charges be laid, it’s likely Thorkelson won’t go anywhere near the United States to prevent being taken into custody like what happened to Strempler. Canada is not likely to extradite him to the U.S.

No one was more overjoyed that counterfeit drugs came from an Internet pharmacy than the pharmaceutical giants. It gave the industry powerful ammunition in its fight against the online upstarts.

Roger Bate, resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C., is author of PHAKE: The Deadly World of Falsified and Substandard Medicines. A study by Bate determined drugs from accredited Internet pharmacies are safe.

“Basically, it’s about as safe, probably not quite as safe, but it’s about as safe as going to your neighbourhood pharmacy to get your medicine,” he determined.

But that is if people are buying from “credentialed sites” approved by CIPA or Pharmacychecker.com, a private entity set up a decade ago to help poorer Americans find cheaper drugs across the border.

However, Bate found there is great risk in buying from “uncredentialed” sites. These are ones not listed with an umbrella organization, or sites contained in spam email selling Viagra. These sites are not only susceptible to counterfeit drugs (Viagra is the most traded fake drug on the Internet) but have been linked to the Russian Mafia, which uses them for identity theft.

“It’s a gold mine for criminals,” said Bate.

Bate said he has only heard positive things about Thorkelson. Nevertheless, that such a leading figure in online pharmacy is alleged to have made such an egregious error with Avastin gives him pause.

But in the same breath, Bate points out that technically, it has nothing to do with the Internet. It was wholesale trade to medical clinics and hospitals.

In the case of Avastin, it’s a liquid drug and is not sold over the Internet because shipment delays can compromise its effectiveness. “As far as I’m concerned, this wasn’t an Internet issue,” said Bate.

Even so, he expects the fake Avastin will result in increased pressure for tighter Internet regulations, which he believes could be tabled this year.

Current FDA law says you cannot purchase drugs from abroad unless you are licensed to do so. However, there is a caveat that FDA will not enforce the law on importation of up to a 90-day supply of prescription drugs for personal use. Drug manufacturers and their state representatives are pushing to close that loophole.

“I think there’s a possibility that these Internet pharmacies will have far more limited reach within a year or two,” Bate said.

Certainly, critics have some valid concerns. The operations are called Canadian Internet pharmacies, yet very little product comes from Canada. Canada mainly takes the orders. The bulk of drugs is sourced from abroad. In fact, the product can’t land in Canada and then be exported elsewhere because that’s against the law.

On Big Pharma’s side, it’s a valid argument that developing new drugs is an expensive investment and prices must reflect that. It’s the old story: It costs $1 billion to make the first pill, and 50 cents per pill after that. But then you read that Pfizer spent US$85 million on Viagra TV commercials in the States last year.

Big Pharma also complains it isn’t operating in a free market. Prices are cheaper in places such as Canada and Europe because the governments cap those prices. And drug-makers can’t act in unison and refuse to sell to a country because that violates antitrust laws. Drug-makers want the U.S. government to pressure Europe to pay more for medicines. Then prices would drop in the U.S., they say. And it must be pointed out the pharmaceutical industry says it charges more affordable prices in poorer countries to reflect their public’s ability to pay.

Despite that variable pricing policy, there are groups within those countries — such as people without medical insurance in the U.S. — who still can’t afford to pay. This is the market for Internet pharmacies. Online pharmacists serve the poor, the uninsured and the people in catastrophic circumstances who can’t afford medications they often need in order to live.

Online pharmacies are a drop in the bucket vis–vis total American spending on prescription drugs. Americans now spend over $200 billion on prescription drugs per year. Internet drug sales from Canada are now only about $500 million (down from about $1 billon in their heyday), or less than a quarter per cent of the market, said Tim Smith, CIPA general manager.

“It’s a pretty steady business but it hasn’t been a huge growth industry,” Smith said. U.S. consumers also buy from Internet pharmacies in Italy, Germany, Britain, Australia and Israel, in addition to Canada.

At one point in the ongoing war, CIPA offered a truce. It proposed Big Pharma let CIPA service Americans who did not have health insurance and who could not afford medications. CIPA estimated it could take up no more than five per cent of the U.S. market, largely because mail-order service had natural limitations such as the 90-day supply restrictions, and dealt in mainly maintenance medications. Big Pharma said no way.

While there is no denying Strempler and Thorkelson made mistakes, there is no denying Manitoba pharmacists did bring about health-care reform in the U.S. In 2006, in direct response to pressure from online pharmacies, the U.S. introduced Medicare Part D, a program designed to help offset drug costs for seniors who have no private health insurance plan.

The program has numerous variations but essentially it assists seniors with payment of the first $2,250 in drug expenses (2006 figures, that have recently been raised). The senior must then pay the total cost of any drug expenses between $2,250 and $5,100. This is called the “donut hole.” Anything above that is considered “catastrophic coverage” and some government assistance kicks in again. Medicare Part D is an improvement but still leaves the patient paying substantial medical costs.

Medicare Part D cut sales from Canadian Internet pharmacy by half — by close to $500 million — and the industry has never recovered. Seniors could not buy their first $2,250 worth of prescription drugs from Canada or they would lose coverage from Medicare Part D. Online pharmacies recovered some of the market by reaching out to those seniors whose drug costs fell into the donut hole, that is, surpassed $2,250. “We’d say, ‘If you know your drug costs exceed $2,250, you might as well order from Canada,'” said one insider.

But Internet pharmacists have not done much to affect Big Pharma’s pricing policies. Guess where the pharmaceutical industry still obtains two-thirds of its earnings? Hint: It shares a border with Canada.

So the Internet pharmacy battle that started in Manitoba 13 years ago continues. The landscape has changed, however. Online pharmacies have consolidated and most of the major companies are now based in British Columbia, where the provincial government is very protective of them because they provide good-paying jobs. The rest are in Manitoba. CIPA is down to just 14 Internet pharmacies in all of Canada.

Looking back, however, it seems ill-considered to portray this as a battle between the drug giants and the three Manitoba mavericks: Strempler, Jorgenson and Thorkelson. Yes, it was Big Pharma and regulatory authorities versus a global shell game perpetrated by Internet pharmacists. The powerful drug-makers depicted them as the bad boys.

But wasn’t the battle really between Big Pharma and a new communications technology called the Internet? The World Wide Web exposed drug manufacturing’s pricing policies. Big Pharma responded by trying to control the Internet.

The web blew Big Pharma’s pricing policy out of the water. It removed national boundaries. It made it almost as if every drug product was for sale next door. Most companies that have seen their bottom lines hurt by the Internet would say, well, welcome to the club. Deal with it. But Big Pharma chooses to fight on. It continues championing the old world order.

MaryAnn Mihychuk, who defended Internet pharmacies during their boom years when she was Manitoba’s minister for industry, trade and mining, sums up Internet pharmacies this way. “The world is ready,” she said.

“It was one of those things where technology just surpassed the regulations. If Canada wasn’t able to supply quality drugs to the U.S., many other countries were going to step in. Stopping Canada wasn’t going to block it.”

bill.redekop@freepress.mb.ca