Our own Icelandic saga

Settlers looking for a better life arrived in New Iceland unprepared for the brutal winter, but those who survived the weather and disease stayed and built new lives; today there are 100,000 Manitobans who can trace a connection to Iceland, their ancestral homeland

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 20/11/2012 (4778 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

RIVERTON — While Nelson Gerrard talks, there’s a great looming distraction behind him.

It’s the local historian’s massive bookcase. It covers one wall and stretches to the top of his home’s three-metre-high ceiling.

The bookcase full of old books is more like a mural, like that famous collage of Dublin doors, very geometric except the shapes aren’t doors but books, books, books.

Some books jut out farther than others. Some little ones look uncomfortably sandwiched beside big ones. Some are uniform, as in volumes in a set — the famous Icelandic sagas, for example — but most are random in size and colour and thickness. There are black and brown leather bounds, and many with those grainy red or green bindings, like the old schoolbooks.

Interestingly, as they are old books, nearly all the spines have the title and author’s name embossed in gold. It seems as if people back then placed great stock in the written word and scholarship and imagination.

"Come here," those books with the gilded letters along their spines keep whispering as Gerrard talks, to the point of being maddeningly distracting. "There’s gold in here. True gold."

It’s hard not to think of everything from gold lettering to high literature when talking about Manitoba’s Icelandic community.

The Icelandic settlers opened a church, school and newspaper — in that order — when they arrived here in 1875. Those were the top things on their to-do list. Get a newspaper going. You’ve got to have a newspaper!

You have to consider what an impressive achievement this was. The newcomers were ill-prepared for our winters — the average temperature in the coldest month in Iceland is about 0 Celsius, although it can drop as low as -15 degrees C, and a miserable wet, cold it is, too — and had to learn how to eke out a living in this harsh environment. Then, within a year, in 1876, about 100 of the Icelandic settlers died in a smallpox epidemic.

The first newspaper was actually a man who went from home to home reading aloud news he’d written out in longhand. That one doesn’t count.

Sigtryggur Jónasson, the leader of settlement here called New Iceland, set up the first actual printed newspaper, called Framfari (Progress). He ran it out of his log cabin in Riverton beside the Icelandic River, 105 kilometres north of Winnipeg. The first edition appeared on Sept., 10, 1877. It was four pages and was published three times a month. Subscriptions to Framfari cost $1.50 a year in New Iceland and $1.75 elsewhere. Subscribers included 39 in Iceland, eight in England, one in France, two in Norway, a scattering of subscribers in Nebraska, Minnesota, Utah, Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa, Illinois, Nova Scotia and Ontario, and 90 in New Iceland. Its largest print was 589 copies.

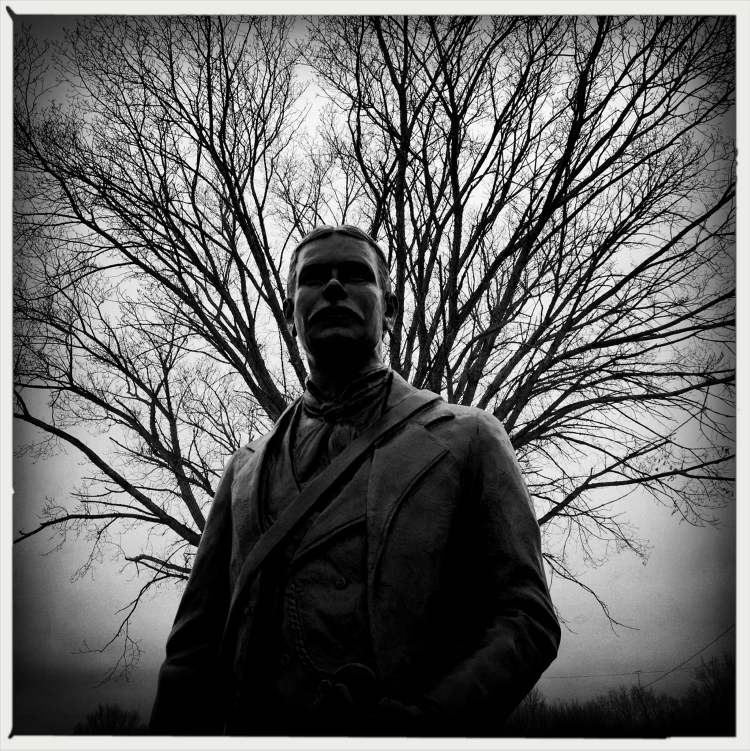

A new statue erected last month in Riverton of Jónasson, the editor, is a good place to start when thinking about Manitoba’s Icelandic-Canadian community. One might even say it was thoughtful of the non-profit Icelandic River Heritage Sites Inc. to erect a statue of Jónasson just in time for this Free Press special edition. It was coincidence, of course. The statue was six years in the making. The community, led by Gerrard, a fifth-generation Icelandic-Canadian on his mother’s side, and other members of the Icelandic River Heritage Sites, raised $40,000 to commission the statue. Jonina Jónasson Britton, 97, Jónasson’s grand-niece, performed the unveiling. The federal government has promised to add a pedestal with historical notes next spring.

Not only would there have been no newspaper if not for Jónasson, there would have been no New Iceland, Gerrard said. Jónasson, called "the Father of New Iceland," was the first Icelander to settle in Canada. New Iceland is the settlement starting just north of Winnipeg Beach and extending 58 kilometres up the Lake Winnipeg shoreline, including Gimli, Arborg, Riverton and Hecla Island.

The more-than-two-metre bronze statue of Jónasson may be a little different from what you’d expect. You might expect the statue of a Canadian pioneer to look like someone who just walked out of the bush, or who is on the way to the Governor-General’s ball. The statue of Sigtryggur Jónasson looks like a school teacher leading a field trip. He’s much younger and less grizzled than you might picture him. He was only 23 when he arrived, has his fob watch chain dangling from his vest pocket, holds a periscope in one hand and compass in the other. Somehow, he looks too young to trust with a compass.

But his directions were good. Iceland was growing and there wasn’t enough farmland in the largely agrarian society for the next generation. So Jónasson decided to catch the wave of European immigration to the New World. The first Icelandic settlers were heading to Wisconsin in the United States. But Jónasson struck up a conversation with a Scot on the ship over who scoffed at the idea. Canada was the superior choice, he told Jónasson. So Jónasson, already a big fan of the British parliamentary system, opted for Canada.

Jónasson arrived in Ontario in 1872 and several hundred Icelanders followed him in the next two years. They tried to settle in Ontario, first in Kinmount, north of Peterborough, and then in the Rosseau district, nearer to Parry Sound. But suitable land was limited and the group elected Jónasson to head a delegation to explore opportunities in Canada’s West. The delegation decided on the western shore of Lake Winnipeg, with its water, timber and grazing land. On Oct. 21, 1885, about 270 Icelanders arrived. The following summer, 1,200 more pulled up on shore.

When I was in Iceland two years ago, a major topic of discussion was a discovery made from the country’s DNA bank. Iceland has the most complete DNA bank in the world, thanks to a government decision in the 1990s that allowed the company deCode Genetics to obtain DNA records of virtually everyone on the island. The decision was made to help search for genetic markers to disease, as Iceland has had a relatively closed DNA pool since its settlement.

The DNA showed that while 80 per cent of male Icelanders trace their origins to Norway, the majority of women came from Scotland and Ireland. About 60 per cent of Icelandic women are of Celtic ancestry. Researchers can tell because Scottish and Irish DNA lineage is mitochondrial, meaning passed along only by the mother. Norse vikings stopped in Scotland and Ireland and took wives and slaves (male and female) before settling Iceland, starting in 874 AD. In essence, the origin of Icelandic people is nearly half Norwegian, half Gaelic: Celtic-Norwegian, we might say today.

Nelson Gerrard collects archival studio photos of early Icelandic immigrants to Manitoba.

— — —

"Where are you from?"

There had always been tales handed down in the Icelandic sagas (historical accounts of Iceland that have been fictionalized to some degree) of some Celtic mix in their blood. But most people were surprised it was so much. Hoerdur Hilmarsson, a former soccer star and the owner of IT Travel in Iceland, told me the DNA study helped explain the six redheads in his family.

Whether that blood relation somehow helped Icelanders blend into Canadian society, where the Scots laid the foundation of everything from industry (starting with the fur trade) to culture to politics, is conjecture. There are similarities, however. Both have shared a belief in egalitarianism and the universality of education. In 1750, when Scots were emigrating to Canada in large numbers, the literacy rate in Scotland for men was over 70 per cent, versus just 50 per cent in England. More than a century later, when Icelanders started arriving in Canada, the literacy rate in Iceland was over 90 per cent.

Also, some scholars have long argued Icelandic literature, like its sagas, bears more resemblance to Gaelic literature than that of Norway. The same is said of its oral storytelling tradition. And both Celts and Icelanders today place great value on reading and literature. Arguably the three greatest modern-day writers in the English language came from Ireland: Y.B. Yeats, James Joyce and Samuel Beckett. Meantime, Iceland’s Halldór Laxness captured the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1955. Iceland had a population of just 160,000 at the time.

— — —

Icelandic newcomers to the western side of Lake Winnipeg suffered terribly. In addition to the smallpox epidemic, there were floods, hunger and their first winters saw -40 C temperatures. Then a religious controversy erupted between two pastors, one who campaigned to relocate. In 1879, Rev. Jon Bjarnason spearheaded an exodus from New Iceland to North Dakota and, to a lesser extent, to the Baldur-Glenboro region of southwestern Manitoba. About three-quarters of the population of New Iceland departed, leaving behind just 50 families, mostly around Riverton and Hecla.

Sigtryggur Jónasson was one of those who stayed. He accused those leaving of being quitters. The departures killed his newspaper, but he moved into other enterprises. He and a partner bought a steamship and got the economy going. The ship was called the Victoria and transported supplies and passengers to and from New Iceland to Selkirk and Winnipeg. Jónasson and his partner also opened a store, logging camps, a sawmill and a boat-building facility.

He was elected New Iceland’s head of council. Commercial fishing became the main industry. Soon, a new batch of immigrants began arriving from Iceland. This time the emigration from Iceland was fuelled by volcanic activity that covered large tracts of land with ash, exacerbating the existing land shortage there.

The period 1883-87 saw the biggest Icelandic immigration. The newcomers also began moving into Winnipeg. Sargent Avenue between Furby and Dominion streets became known as the Icelandic District. Icelanders began settling the area at the Narrows on Lake Manitoba in 1890.

Even with difficult times, Icelandic people assimilated into Canadian society more readily than some other immigrant groups, Gerrard said. "They took to Victorian values like ducks to water," he said. Icelandic people held British customs in high regard to the extent that many became eager followers of the British Royal Family.

They still had to adapt, however. One example was in women’s style in clothes. Icelandic women wore something called a skotthufa, a black skull cap with a long black tassel that fell off to the side. Skotthufa literally means "tail hat."

Women would braid their hair into elaborate loops around their heads. "One of the first things people said to the women off the boat was they could send the hat back to Iceland," said Laurie Bertram, an Icelandic-Canadian scholar who wrote her dissertation on Icelandic-Canadian cultural history at University of Toronto.

Another non-starter in the new society was the women’s traditional black dresses that opened in front. Women wore their top button done up, but left the next three buttons undone. A white fabric was inserted to cover the woman’s chest. "It would basically look like your boobs were busting out," said Bertram. They soon adopted the more demure Victorian look of the times.

In total, about a quarter of Iceland’s 80,000 population in the 1880s immigrated to North America. "The immigration had a positive effect on Iceland because one of the first things people did after they arrived was send money back home," said Gerrard.

New Iceland land was the exclusive preserve of Icelandic settlers up to 1897, under a government agreement. Then it was opened up and Ukrainian pioneers began to arrive, followed by newcomers from Poland and Hungary.

Jónasson played a lead role in New Iceland his entire life. He became a founder of the Icelandic weekly newspaper, Lögberg; a benefactor of the First Lutheran Church; an immigration agent for Manitoba (Manitoba absorbed New Iceland in 1881 when the postage-stamp province’s boundaries extended farther north); a homestead inspector; and a member of the legislature for two terms. He also successfully lobbied Ottawa and CP Rail to build a railroad to Gimli.

Due to his efforts, Manitoba has the largest settlement of people of Icelandic descent outside Iceland. Today, about 100,000 Manitobans trace ancestry back to Iceland.

— — —

Coffee, or "kaffi," thy name is Icelander. These folks love their coffee so much that they’ll strain it through a sock. And they like it so strong that it smells like it was strained through an old sock. One woman in Gimli said if there is an Icelandic-Canadian out there who doesn’t like coffee, someone should put their portrait on a poster.

It’s called a "kaffi poki," a kitchen implement that literally means "coffee bag." It’s a bag used to filter coffee grounds. The sock part is made from a pure cotton muslin cloth sewn onto a round brim with handle, so that it looks like a miniature butterfly net. You put the coffee grounds inside and pour. Icelanders brought the technology with them to Canada.

At the height of the smallpox epidemic of 1876, a medical official reported visiting New Iceland, where people were dying and had little food to eat except fish. But when he went into a home, he was offered coffee. He was shocked. Coffee was considered a luxury in English households, where they mainly drank tea, which was less expensive.

"Canada was all about tea and people just couldn’t believe it," said researcher Bertram. "Even at their lowest point, Icelandic people still had coffee."

On the other hand, if Icelanders went to someone’s house and weren’t offered coffee, they found that "really foreign and outrageous."

Coffee gained a strong foothold in Iceland probably starting in the late 1700s. "Iceland is a very dark country in winter, with little daylight, and it can be difficult to get out of bed. So coffee became this important way for people to socialize but also to wake up, to get up energy levels," said Bertram.

But that also led to problems. Coffee was almost like "a controlled substance" among some Icelanders who would access the beverage even when they could barely put food on the table. "You see signs of caffeine addiction in some historical records, people spending a lot of their income on coffee. It’s almost like a medicine to them, and there is speculation it was women’s drug of choice."

The love of coffee manifested itself with the Wevel Café on Ellice Avenue in Winnipeg’s West End where many Icelanders first settled.

"That was where a lot of Icelandic men would go and sit and drink coffee, where a lot of local businessmen would go to socialize," said Bertram. Icelandic-Canadian cartoonist Charlie Thorson would hang out at the Wevel and do his sketches. The story goes that he had a big crush on one waitress and his sketch of her later became Snow White when he worked at Walt Disney Studios.

It’s a Scandinavian custom to have strong coffee. It’s why the Icelandic River Heritage Sites group in Riverton came up with the brilliant idea to sell its own blend of Icelandic-strength coffee, Jola Kaffi, Icelandic River Roast Coffee. They had a local company make a special blend and began selling the beans as a fundraiser. It’s got oomph, that’s for sure. The coffee has already netted the heritage group $40,000 in just four years.

In Gimli, it’s available at the Reykjavik Bakery and the New Iceland Heritage Museum. In Winnipeg, people can email sekjon1@mymts.net.

— — —

When I was in Iceland, I hung out with an American couple who were staying at the same hotel. One evening while relaxing at an outdoor café in a cobblestone courtyard — Iceland is very European — the man said to me that he had met only one person he knew to be of Icelandic descent in his lifetime. I replied that if I didn’t meet a person of Icelandic descent by lunch time, there was something the matter.

Icelanders settled in more than 50 locations across North America. Locations in Manitoba include Gimli, Riverton, Arborg, Lundar, Lake Manitoba Narrows, Reykjavik (at the far north of Lake Manitoba), Libau, Selkirk, Piney, Baldur-Glenboro, Swan River and Pipestone.

Towns In North Dakota include Cavalier, Mountain, Edinburgh and even Pembina, Roseau in Minnesota and Helena in Montana.

It’s not just their numbers. Icelanders are getting to be sixth-generation Canadians. That’s a point at which it becomes hard to hold onto your culture. Yet their presence in Manitoba is as strong as their coffee.

There are too many Icelandic cultural institutions in Manitoba to mention but here’s a few: the Icelandic-Canadian Frón (Winnipeg Chapter of the Icelandic National League); Gimli Icelandic-Canadian Society; Icelandic-Canadian Club of Western Manitoba; Icelandic River Heritage Sites Inc.; New Iceland Heritage Museum; Lestrarfélagið, the Icelandic reading society. Icelandic-Canadians also belong to the Scandinavian Cultural Centre. There’s Íslendingadagurinn, or the Icelandic Festival of Manitoba, in Gimli every summer. Gimli is a popular destination that feels like a coastal town.

Iceland also has Atli Ásmundsson, Iceland’s consul general in Winnipeg. The popular Ásmundsson will be leaving this spring and a big sendoff is planned. It also has a Chair of Icelandic Studies, Birna Bjarnadóttir, at the University of Manitoba; the only such position at a North American university.

There was the Iceland Express, an air service that began in 2010 and initially offered twice-monthly direct flights to Iceland in summer, then weekly flights. It seemed too good to be true and it was; the flights have stopped. But that hasn’t slowed travel between Manitoba and Iceland for people wanting to research their family histories.

Then there’s the Icelandic National League of North America. Its annual convention was in Brandon this year and is next in Seattle. Its conventions includes guest speakers and lots of socializing.

"We sing and dance and go to the bar Friday and Saturday nights. We used to stay up all Friday night, but those days have passed because the young people can’t do it anymore," said Vi Bjarnason Hilton, a convention veteran.

So it was apropos for the Icelandic community in Riverton to pool its resources and erect the statue of Jónasson. The statue looks out on the bank of the Icelandic River on land he once owned. He began the massive chain of events; not just a family tree, but more like a taiga forest. Icelanders are found in all walks of life. A list of prominent Icelanders would be too long. They are so integrated in our society that they aren’t noticed for their ethnicity — until the Icelandic festival comes around. Then the chest-thumping starts.

Although that still doesn’t explain why the culture remains so strong.

Joel Fridfinnsson, 27, a grain farmer near Arborg, just returned from another visit to Iceland. Why do people like him, a sixth-generation Icelandic-Canadian, hold onto their culture so tightly?

"One reason is there are such great genealogical records in Iceland. It’s so very easy for people to access their genealogy, and go back and find where they’re from and meet relatives. That really helps to keep the two communities together," said Fridfinnsson.

It also has appeal to non-Icelandic people.

"Most people have some interest in ancestral roots and Iceland seems to have a particular attraction for many people, even people who are not Icelandic," said Ryan Eyford, University of Winnipeg history professor. "The culture, its nature, geology, it’s something that people have a lot of interest in."

You can’t overlook its underdog status, either. It’s the smallest of nations, an island stuck off in the ocean by itself, yet somehow its profile in the world is much larger than its 320,000 population. It’s as if Lichtenstein had muscled itself onto the world stage.

"Maybe because it’s weird or interesting or strange," Eyford said of Iceland. "The Romantic movement in Europe was fascinated by Iceland. People saw it as a relic of medieval culture. So it became one of those places in world where people imagined they could visit history."

— — —

Every word in Icelandic, a medieval Norse language, starts with the emphasis on the first syllable. So there’s no guesswork or worry about making the embarrassing social faux pas of putting emphasis on the middle or last syllable.

Language is one of the hardest things for ethnic groups to keep alive in a new country, and Icelandic-Canadians are no different. But they try. The first Friday afternoon of every month, people gather at the Scandinavian Cultural Centre for "kaffi tíma," coffee time, and "að tala," to talk, in Icelandic only. The centre also offers Icelandic-language night school classes.

In Gimli, at Amma’s Tea Room, women gather Wednesday afternoons to speak Icelandic and drink coffee.

But if language is slipping away, the high value Icelandic-Canadians place on books is not. Like their forefathers, they are power readers.

"When they came from Iceland, what did they bring? They brought trunks of books," said Lorna Tergesen, who runs a bookstore out of the famous Gimli landmark, the H.P. Tergesen & Sons store, which has operated since 1899.

The Icelanders all brought trunks with leather-bound Icelandic sagas and other books. Not only that, those first-generation Icelandic-Canadians were already translating major English-language books into Icelandic.

Tergesen’s is like an old-fashioned department store. In one section is the bookstore. People who haven’t travelled throughout rural Manitoba may not realize how remarkable that is. The town of Gimli has a year-round population not much greater than 2,000. Cities up to five times its size, such as Portage la Prairie, Dauphin, Winkler, Morden and Steinbach, don’t have general bookstores. (Some have religious book stores.)

Tergesen’s bookstore started with the second generation of Tergesen owners, Svenn Johan and Lara. Lara was a school teacher and believed strongly that people needed to read. So she ran her own library out of the store before the public library arrived. When Terry and Lorna Tergesen took over the store in the mid-1980s, they reopened the bookstore.

It’s tough to make money selling books these days. "I can justify it as part of the whole (store). You come in here and there’s something for everyone," said Tergesen. Digital publishing "will inevitably hurt the industry but people still have a passion for books."

Local Icelandic-Canadian writers today include David Arnason, Bill Valgardson, Martha Brooks and Caelum Vatnsdal. Historically, Guttormur J. Guttormsson, originally from Riverton, wrote poetry. Novelist Laura Goodman Salverson, who was born in Winnipeg, won the Governor-General’s award twice, for The Dark Weaver in 1937 and for her autobiographical Confessions of an Immigrant’s Daughter in 1939.

There is the Icelandic-Canadian newspaper Lögberg-Heimskringla, the oldest continuously publishing ethnic newspaper in North America, printed bi-monthly out of Winnipeg, and magazine Icelandic Connection. An Icelandic Collection of books was established at University of Manitoba library. The library also has an Iceland Reading Room with the Dr. Paul H.T. Thorlakson Gallery showing Icelandic artwork and the Icelandic sagas in vellum manuscripts.

At the Free Press, we never had to look far to see the influence of Icelandic-Canadians. It seems hard to believe now but three Icelandic giants of the newsroom have died in the past two years: Hal Sigurdson, Tom Oleson and Jon Thordarson.

Sigurdson, who retired in the late 1990s, was the thinking man’s sportswriter, providing insight instead of outrage. Oleson liked to joke of his insignificance and made self-deprecation into an art form, but the truth was we were so lucky to have him. Thordarson wasn’t a writer — he was photo editor for many years — but he was the person people relied on to keep things sane in the daily chaos that is a newsroom. He was a rock to many people.

They are sorely missed.

One final story. It’s not unusual for immigrant groups to have a local benefactor, someone from their new country’s establishment who takes an interest in them. Frederick Temple Blackwood, better known as Lord Dufferin, was such a person to the Icelandic-Canadian community.

Lord Dufferin, born in Ireland and Scottish on his father’s side, had a soft spot for Icelanders. He had once visited Iceland and appreciated Norse literature. As Canada’s governor general, he advocated for the Icelandic immigration to Canada. He once claimed that he had "staked his personal reputation on the success of the Icelanders."

But things weren’t going well. New Iceland had been placed under quarantine on Nov. 27, 1876, for its smallpox epidemic. People were hungry and dying. A hospital had been thrown together in Gimli and a quarantine station built at Netley Creek. Canadian officials were starting to voice concerns that the newcomers might not have the constitution to withstand the rigours of Canada’s climate and that it may have been a mistake to permit their entry.

Lord Dufferin visited New Iceland shortly after the epidemic ended in 1877. He toured the settlement to see for himself and to boost morale.

"I scarcely entered a hovel at Gimli that did not contain a library," he reported in a speech he gave shortly after in Winnipeg.

It was more than observation. It was a statement. He was implying that with such an emphasis on reading and books, these people would succeed. They would overcome the hardship. They would become major contributors to Canada yet.

Almost 140 years later, the evidence is in.

bill.redekop@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Friday, November 23, 2012 2:55 PM CST: adds slideshow