Winnipeg author’s novel a product of rejecting long-held beliefs

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/08/2021 (1581 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Growing up in an evangelical church in the 1960s, I was well-acquainted with Operation Auca, the story of the killings of five American missionaries at the hands of Waorani Indigenous people in Ecuador.

The deaths of Peter Fleming, 27, Jim Elliot, 28, Ed McCully, 28, Roger Youderian, 31, and Nate Saint, 32 on Jan. 8, 1956 made headlines across North America and sparked a continent-wide Christian missionary movement.

The men and their wives had gone to that South American country to evangelize the tribe, known to them as Aucas in the Quechua language, or “savages.”

Members of the tribe, who were known for their ferocity, avoided contact with the outside world. The missionaries were determined to reach them and convert them to Christianity.

Several years after the deaths of the missionaries, many of the Waorani did become Christians due to the efforts of Elisabeth, the widow of Jim Elliot, and Rachel, Nate Saint’s sister — including some members of the tribe who were involved in the killings.

That story was imprinted on me through books and Sunday-school stories. So I looked forward to reading Five Wives, the 2019 novel by Winnipegger Joan Thomas.

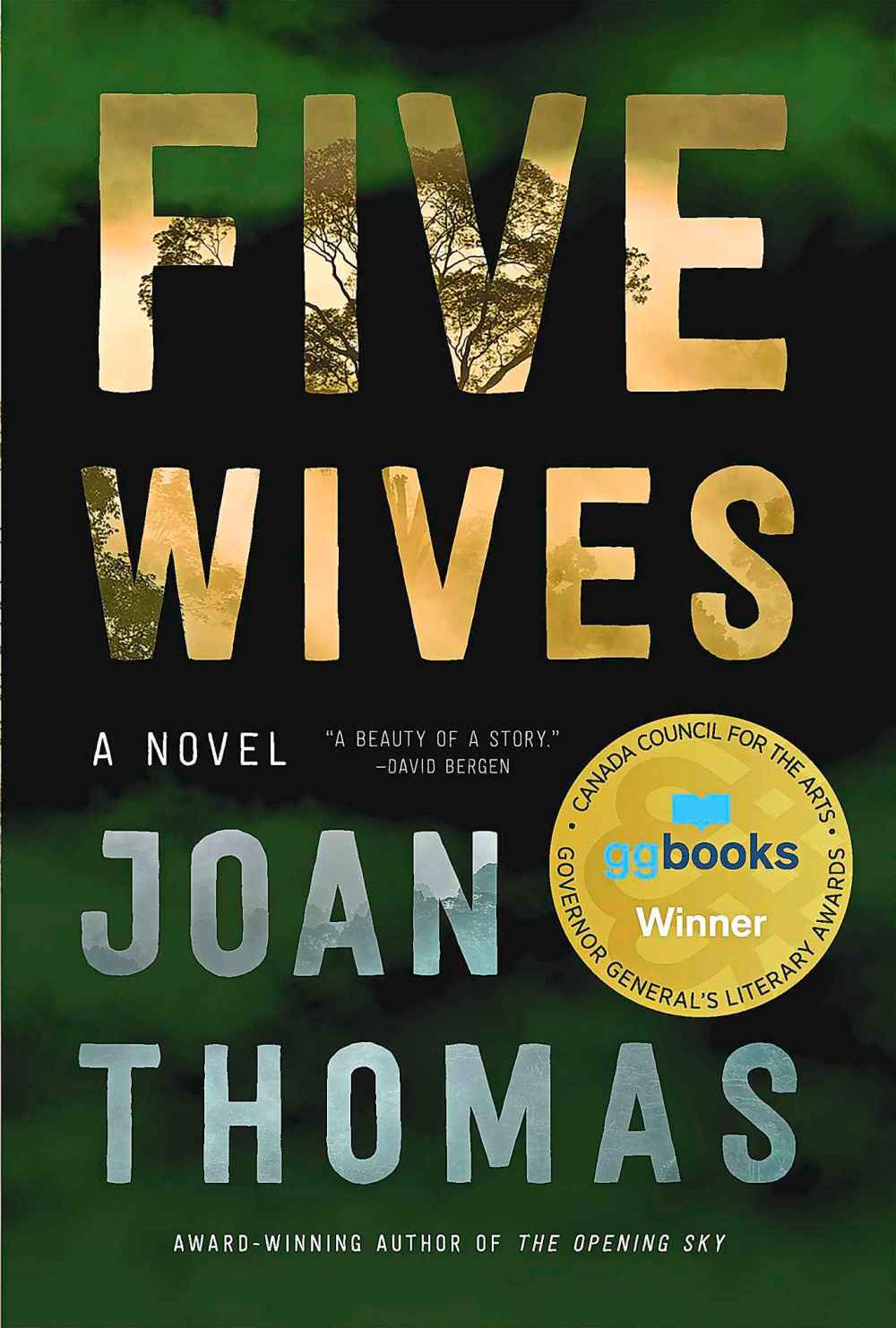

In the book, which won the 2019 Governor General’s Literary Award for Fiction, Thomas writes about the experience from the perspective of the women the missionaries left behind, focusing on their struggles with grief, doubt and each other.

After reading Five Wives, I met with Thomas on a pleasant morning in Kildonan Park to find out more about her, and what prompted her to write the book.

Thomas had a traditional evangelical upbringing. After graduating from Providence University College, she went on to studies at the University of Winnipeg. It was during those years she began to deconstruct her faith.

“In those years I felt terribly hungry to know the wider world,” she said of how she decided to leave the Christianity of her upbringing behind. “I felt I had a lot of catching up to do and I didn’t spend a lot of time looking back.”

What prompted her interest in the story was a 2011 article in the New Yorker about how the missionaries co-operated with oil companies in the 1950s and 1960s to open the Waorani lands for oil exploration.

As it turns out, they not only wanted to bring the Gospel to the Indigenous inhabitants of the region, but also to help them move into a tiny protectorate so oil companies could freely exploit their former lands.

That was a different side of the story she didn’t know anything about, one she hadn’t heard in the gripping tales told in books about the missionaries.

“It’s like the story we have been told all these years was preserved in amber,” she said. “Nobody had taken a look at the political, cultural and environmental impacts.”

She also came to see the book through the lens of the Canadian context, noting the similarities between what happened in Ecuador and what happened in Canada as missionaries were sent to Indigenous people in this country to be converted to the Christian faith.

That was a time, she said, when Indigenous people “were viewed as heathen, benighted, ignorant and lost,” a period many Canadians today are feeling regret over.

As for the book’s reception, the response has been mostly positive.

“There are two kinds of readers; those who grew up evangelical with the story, and others who see it as completely foreign and strange,” she said, adding some churchgoers have questioned her motives for writing it.

Thomas is not without empathy for the missionaries; as someone who grew up evangelical, she understood their world and the way they perceived God’s call on their lives.

“It’s pretty hard to disentangle all the strands between what you want and what you think God wants,” she said, noting that world can be incomprehensible to outsiders even as it makes perfect sense to those within it.

Despite the deaths of the missionaries, “according to the terms of their mission, they succeeded,” she said. But if you look at it another way, she added, it was just another form of imperialism or colonization of Indigenous people.

Today, some members of the Waorani tribe are at the forefront of the fight against climate change, resisting further oil exploration on their traditional lands.

In that context, Five Wives raises questions about exactly who the “savages” in the story were.

“The missionaries thought they were saving the Waorani, and it turns out the Waorani are fighting hard to save all of us,” she said.

faith@freepress.mb.ca

The Free Press is committed to covering faith in Manitoba. If you appreciate that coverage, help us do more! Your contribution of $10, $25 or more will allow us to deepen our reporting about faith in the province. Thanks! BECOME A FAITH JOURNALISM SUPPORTER

John Longhurst has been writing for Winnipeg's faith pages since 2003. He also writes for Religion News Service in the U.S., and blogs about the media, marketing and communications at Making the News.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

The Free Press acknowledges the financial support it receives from members of the city’s faith community, which makes our coverage of religion possible.