Two hearts and a squeaky cart

Taking care of business down the Red River Trail

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/07/2022 (1256 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Whither thou goest I shall go

When Jean-Baptiste Lagimodiere married Marie-Anne Gaboury in Maskinonge, Que., he assumed she would be the typical wife of a voyageur and wait nicely at home for those odd times his wanderings might bring him back to her. She assumed differently. She was his wife and wherever he went, she was going along. Apparently communication wasn’t their strong suit. Everyone, including Jean-Baptiste, tried to convince Marie-Anne of the folly of a French-Canadian woman going on a canoe trip of several months with a bunch of wild-living voyageurs, never mind the impossibility of her making a life out west with all the uncertainties of the fur trade. She would never survive. Amazingly, Marie-Anne convinced the boss of the company to let her go. But nobody was going to baby her. She might not have to paddle or carry a pack over the portages but she would have to take care of herself.

She didn’t know it at the time but in stepping into that canoe, she left her home in Maskinonge forever and entered the history books as the first white woman to live in the Canadian West. Whenever she could, she joined Jean-Baptiste on his ventures: travelling for weeks on end by cart, canoe and horseback, participating in the buffalo hunt or heading far into the interior on diplomatic missions. She had babies here and there and often gave them nicknames after the places where they were born. ‘La Prairie’ was born after Marie-Anne’s horse broke free and went galloping after a stampeding herd of buffalo. After an eternity she managed to slow the horse to a trot and slip to the ground. A very worried Jean-Baptiste found Marie-Anne and helped her give birth to her first son. The seventh of Marie-Anne’s eight children, Julie, would become the mother of Louis Riel.

My wife Patty’s relationship with me has some similarities to Marie-Anne with Jean-Baptiste . I had bought a home in Point Douglas with the intention of bringing guys in off the street. It didn’t turn out so well, and by the time Patty and I started going together I was all alone in that big house. Patty was over one evening, and as we were talking on the couch, the phone rang. After answering the call, I returned to Patty, visibly shaken. It had been Abraham — a guy who used to live there with me. He was high on something and called to let me know that he intended to kill me. After trying to absorb the news, I thought it was time to ask an important question. “Patty, I don’t know where God is going to call me and I have no guarantees that it will be a safe place. It might cost me my life. Would you be willing to enter an unknown like that with a guy like me?” Without hesitation Patty answered, “If God would lead us down that kind of path, it would be the safest place of all.” Wow. I knew it was time to give her the poem I had written months before. So I launched into it. My Patty. Come fly with me. Enough are satisfied with walking, and will not take the risks which give them air.… By the time I was done, Patty’s eyes were moist and instead of a verbal “yes” she simply nodded her head.

We did fly together, through turbulence and beautiful skies. But when I started thinking about doing a two-mile-an-hour, eight-week-long trip on a bumpy Red River cart, I was pretty sure Patty would be a lot less thrilled with the idea than Marie-Anne Gaboury. I also knew I wouldn’t go without her. I predicted her response. She laughed. Out loud. But before she could say “No way,” I jumped in and said I didn’t want an answer now. “Let’s just see if God speaks anything into your heart.” I knew I didn’t want to be the one to convince her. Imagine being three days down the road when the rain was pouring and the ticks were crawling if I had talked her into it.

You wouldn’t guess what changed her mind. Patty worked as a companion to an elderly woman, a proper English lady, whose response to anything unusual was, “That’s just terrible!” So Patty felt pretty safe in telling her my crazy Red River cart proposal. Freida’s reply? “I think that’s just marvellous! What are you going to do? Sit on a couch the rest of your life?” A response that out-of-the-blue must be the word of the Lord!

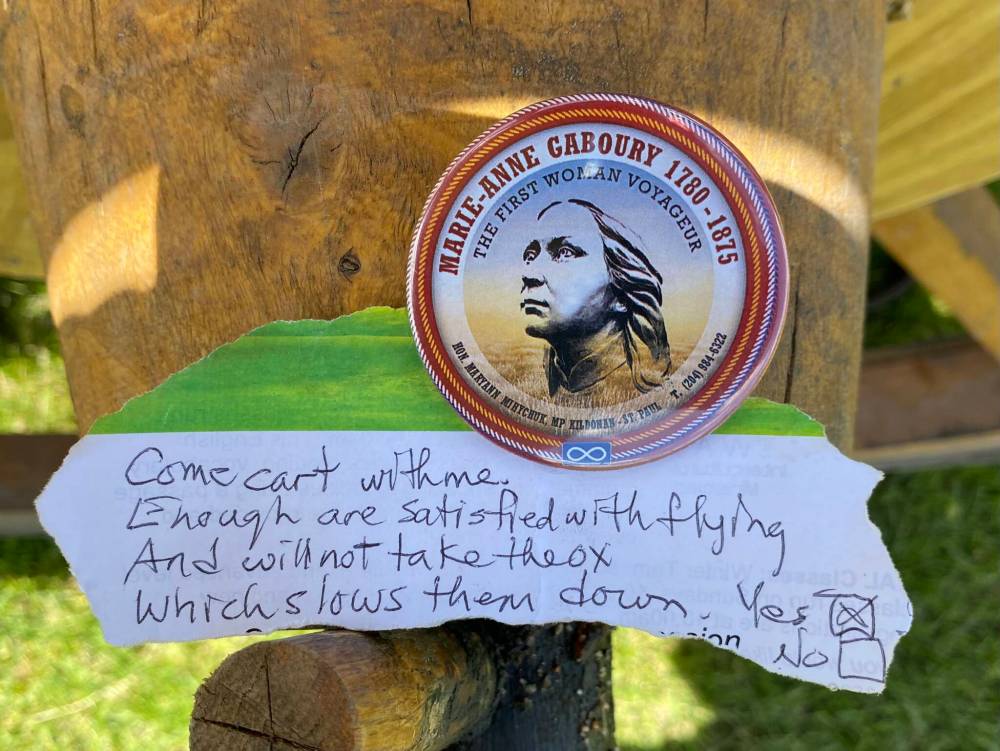

In church a few weeks later, I scratched a revised poem on the church bulletin. Come cart with me. Enough are satisfied with flying, and will not take the ox that slows them down. I showed Patty, and she checked off, “Yes!”

Meet the family

I generally feel a little nauseated when people name their vehicles. (“Seriously? It’s a stupid piece of metal!”) So, with a measure of embarrassment I introduce to you our family on the Red River Trail:

Patty and Terry: Mom and Dad

Zik: Our ox. Short for Bizhiki — Anishinaabemowin for ox or buffalo. So yes, our ox is called Ox.

Vincent: Our ‘Van’ home on the ‘Go.’ Sometimes called Our Vincent, or Our V or just RV.

Rene: The Cart. (If it even exists. Its persistent squeaking seems to say: “I don’t think. Therefore I am not.”)

Blake: Two-wheeled electric scooter.

A simplified day on the trail looks like this: I harness up Zik to Rene. I make sure Blake is hanging in his hockey bag from Rene’s north end. Patty jumps on Rene with me to ponder deep mysteries about God and His Creation. After a mile or two Patty takes Blake and jets back to get Vincent. Patty with Vincent and Blake leapfrog Zik, Rene and I to find a good spot for the night. After maybe 12 miles on the road, us three travellers plod into camp and Rene gives one final squeal of exhaustion from being just too tired. I stake out Zik and fire Blake back into his cage. Only then can I climb into Vincent to notice the vase of yellow flowers on the table, and enjoy the masterpiece Patty has created for supper.

Are you confused yet? Nauseated?

Trail mix

Today Patty decided to make a Red River specialty for supper. Richeau: pemmican stir-fry. Surprisingly delicious! Pemmican — a mixture of dried, pulverized buffalo meat and rendered buffalo fat — was the perfect food for the trail. It was high in energy, didn’t spoil and didn’t need any preparation (unless you wanted to go gourmet and make rubaboo or richeau). Pemmican also has the reputation for tasting kinda disgusting. Which tells you how impressive it is that Tim at Timothy’s Country Butcher Shop actually made the stuff taste good. And then he loaded us up with a journey’s supply of it!

Takin’ care of business

The signature song of Bachman-Turner Overdrive has been referred to as the ‘the provincial rock anthem of Manitoba.’ Its title could just as well be applied to a song sung by earlier Manitobans — a family of Métis taking care of business as they travelled across the prairie. Translated from Michif, it goes roughly like this:

We are going to Turtle Mountain,

We go in a Red River cart,

We wear moccasins, we eat pemmican,

We wipe our arse with birch bark.

I wonder how birch bark compared to a page from an Eaton’s catalogue? My experience taught me that glossy pictures of “The Homesteader’s Bible” were just too slippery to do a good job, but if you crumpled them up first, their wipe-ability was greatly enhanced. And of course, before serving their ignoble duty, the colourful pages provided some good reading entertainment in the otherwise unstimulating confines of the outhouse.

More than once I’ve gone to a Mongolian outhouse and committed to the task at hand before realizing there was no available paper. At that point there was nothing for it but to open my wallet and start the clean-up process with the smallest denomination bill I happened to be carrying. I’d sadly work my way through ever larger bills until the job was done. But seeing as the 10 tugrig note was worth about one cent, I’d generally come out ahead of where I’d be had I spent the money on actual jarliin tsaas.

That reminds me of the story of the Mennonite who deliberately threw a $20 bill into the outhouse hole. Yep. Apparently he had accidentally dropped a nickel down below but couldn’t work up the courage to go and get it. Desperate times call for desperate measures so he did what he had to do to motivate himself to take the plunge. Even Randy Bachman, though not a Mennonite, knew the value of hard-earned money:

If your train’s on time, you can get to work by nine,

And start your slaving job to get your pay …

And we be taking care of business (every day)

Taking care of business (every way)

We be taking care of business (it’s all mine)

Taking care of business, and working overtime.

And now it’s time for me to leave my Red River cart on the trail and head into the woods. I hope I find some big leaves. What does poison ivy look like again?