Getting fleeced: from sheep to skein

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/05/2022 (1290 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When you need a haircut, you really need a haircut. And Yo-Yo Bah needs a haircut.

It’s the last day in April, and the sheep has been waiting all year to get shorn. For humans, that can mean looking shaggy, dishevelled and pre-historic. For Yo-Yo Bah and the other 37 sheep at Long Way Homestead — including Alexander Lambilton, Apollo, Mr. Sinister, Sage, and Shadrach — it means carrying around a lot of extra weight, which can be both uncomfortable and a hindrance to their life if the fleece reaches an extreme length.

An unshorn sheep is an unhappy sheep, and an unhealthy one at that. So a haircut is as much a wellness procedure as it is a grooming opportunity.

Even if they didn’t make the appointment themselves, the sheep — who typically produce around four pounds of wool each — don’t mind the trip to the salon, says Anna Hunter, who with her husband Luke Palka runs the homestead about a 45-minute drive east of Winnipeg, in the town of Ste. Genevieve. At the homestead, they run the province’s only operational wool mill, make their own natural dyes, and run workshops, while raising two children.

The couple had big things planned for the big haircut: a shearing festival where community members could learn more about the animals, the wool, textile and fibre industry, and the homestead’s fibre processes. A chance to interact with textiles and their sources, and to understand the benefits of domestic production.

But it started raining, the festival was cancelled, and shearer Stacey Rosvold could only get to three members of the flock before the slippery conditions got too dangerous to keep going.

Rosvold has sheep of her own, but spends a good deal of her year on the road, travelling from farm to farm to help sheep shed their heavy coats of fleece. It’s hard work: she has to ensure the animals stay still and calm while handling the super-sharp shears. Just as a hairdresser tells you to look down or turn your head, Rosvold attempts and succeeds in controlling the shearing process. It’s as much athletic as it is cosmetic.

Shearing has to be done by hand, Hunter says, and there is a scarcity of experienced shearers in the province, which makes Rosvold a busy person: in the month of May, she was only home for three days, spending the bulk of the month shearing across the Prairies. This year, she estimates she will shear more than 20,000 sheep.

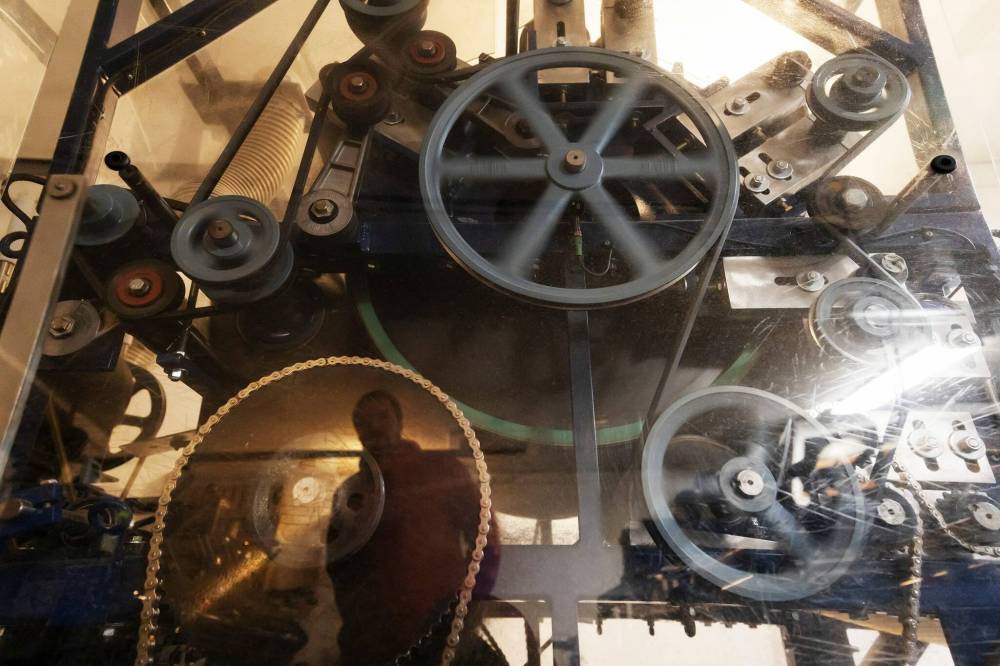

Once the fleece is removed, it’s taken to the mill, where it is scoured, dried, picked, and combed, before the fibre can become batting or roving, which can then be spun into yarn.

It’s a laborious process, but Hunter says it’s worth it: wool is hypoallergenic, flexible, relatively fire-retardant, odour resistant, hygroscopic (temperature regulating) and most importantly, renewable and biodegradable. It can be grown and shorn annually, while unused fibres can be returned to the soil to decompose.

For Yo-Yo Bah, it’s a little bit much. But the sheep will get a haircut soon, Hunter says. When you need a haircut, you really need a haircut.

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com