Misfit mid-’90s teens long to leave their mark

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/01/2023 (1065 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

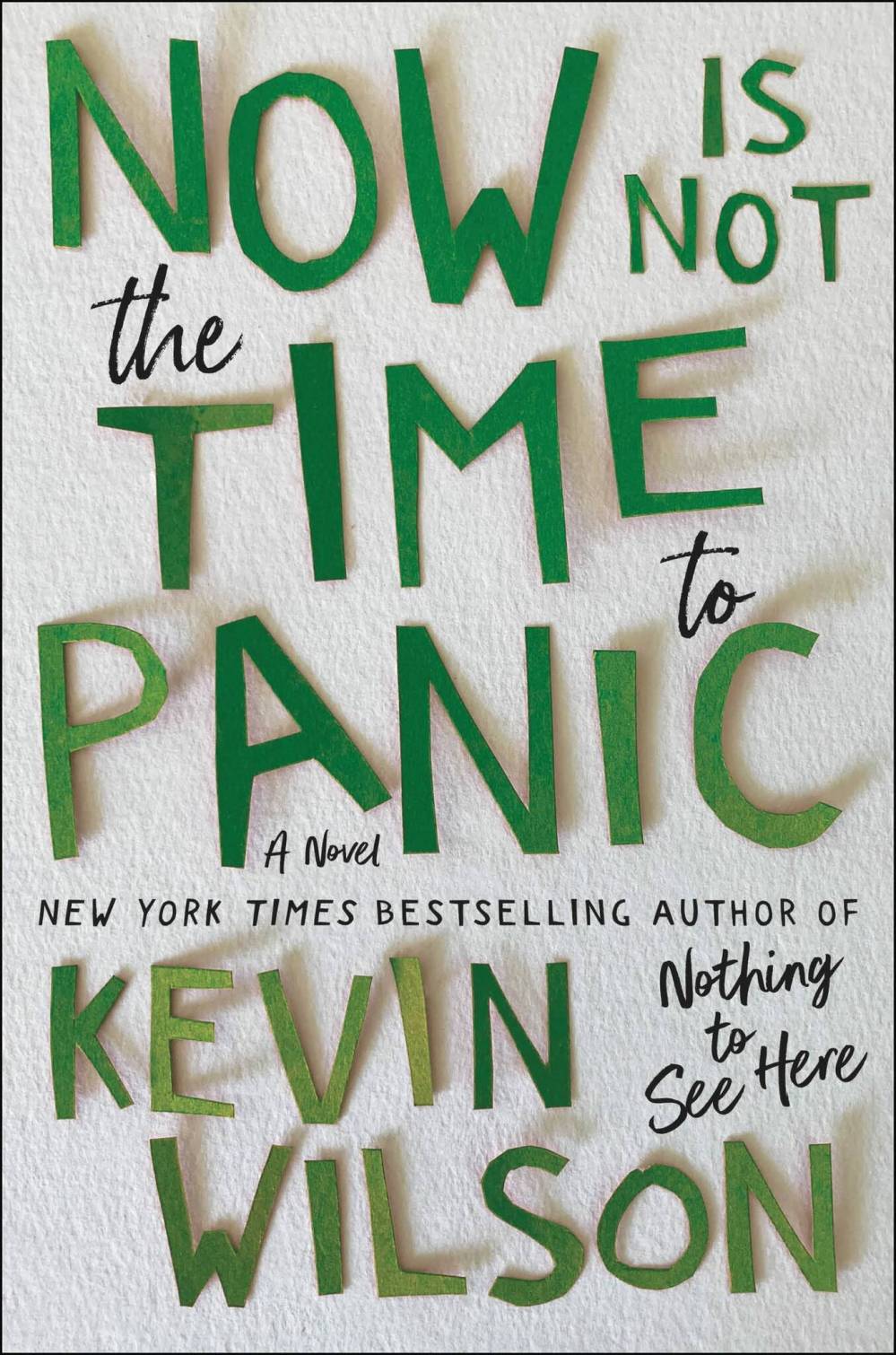

American novelist Kevin Wilson has made a name for himself with books that feature unusual characters and outré plots.

The Family Fang is about the children of a couple of performance artists struggling to recover from the damage their parents did them in the wake of their apparent disappearance, while Nothing to See Here is the story of a once-promising young woman tasked with looking after two kids who are prone to bursting into flame.

Neither situation should be relatable, but the Tennessee author steeps his slightly (or outrageously) fantastical tales in an abiding sweetness, sharpens them with a mordant wit and creates characters who feel deeply real.

Now is Not the Time to Panic

He told the New York Times recently: “I tend to love books where freakishness isn’t presented as something inhuman, but rather an affirmation of what it means to be a human being trying to survive in a very inhospitable world.”

Wilson’s latest is, according to the author’s foreword, a more personal story stemming from a very specific incident in his teen years, and something about that reality, oddly, makes it less believable. Even without the heads-up, you can feel the writer straining to connect the reader to something very important to him; despite the valiant effort, it mostly feels like a case of “you had to be there.”

Now Is Not the Time to Panic is set in 1996, when Frankie Budge is 16. She’s aimlessly puttering through a hot Tennessee summer, dealing with her semi-feral 18-year-old triplet brothers and a mother who’s still recovering from being dumped by Frankie’s father. (Though it’s not nearly as funny as Wilson’s other books, there are plenty of zingers. Of her mom’s boyfriend, a reporter for the local papers, Frankie says, “He was like if Lester Bangs wrote about Fourth of July cake contests instead of the Stooges.”)

At the Coalfield pool, she meets Zeke. His mother is also dealing with the fallout of an unfaithful husband, so they are staying with Zeke’s grandmother for the summer.

Recognizing each other as artistic misfits, Zeke, who draws, and Frankie, who writes, are drawn together in a relationship that feels more like-minded than romantic, though they do spend a lot of time making out.

Bored and listless, trapped in small-town lethargy, they itch to do something meaningful. Zeke hits upon the Banksy-ish idea of making an enigmatic, anonymous piece of art, copying it and posting it around town.

As if channelling an outside voice, Frankie comes up with the phrase: “The edge is a shantytown filled with gold seekers. We are fugitives, and the law is skinny with hunger for us,” which Zeke illustrates.

They never anticipate that their innocent art project will seize the imagination and fuel the paranoia of people well beyond Coalfield’s borders, with terrible repercussions.

It’s easy to see that the phrase’s David Lynchian menace and Zeke’s disturbing imagery might make people uneasy. But the way the story is told — in first person, with adult Frankie looking back as she deals with the potential exposure of her secret years later — focuses too much on her own small world and her obsession with the poster project. The idea of a widespread meme, echoing the Satanic panic of the 1980s, never feels quite believable.

If the central conceit of Now Is Not the Time fails to capture the imagination, Wilson does convey what non-mainstream passions and fandom were like in the pre-internet ’90s — how difficult it was to find your tribe and your cultural touchstones when you had to seek things out on your own, without algorithms and with the knowledge that you knew nothing at all.

“You were never quite experiencing anything in a linear way…” Frankie recalls. “Every single thing you loved became a source of both intense obsession and possible shame. Everything was a secret.”

Jill Wilson is a Free Press copy editor and writes the weekly arts newsletter Applause.

Jill Wilson writes about culture and the culinary arts for the Arts & Life section.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.