Road map to reconciliation

Chief Robert Joseph shares personal residential-school story — and a potential path forward

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/09/2022 (1176 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In August 2022, Pope Francis apologized — finally — for Roman Catholic complicity in “cultural genocide” and the Indian Residential School system.

“I am sorry. I ask forgiveness, in particular, for the ways in which many members of the Church… co-operated… in projects of cultural destruction and forced assimilation…”

In his stirring and hopeful memoir of overcoming his abandonment to St .Michael’s Residential School in Alert Bay, B.C., Kwakwaka’wakw Chief Robert Joseph notes his disappointment at a 1998 expression of “regret” by then-Indian affairs minister Jane Stewart. “Yes, the word ‘sorry’ was used in the speech, eventually,” he says, “but what the government officially offered was regret.”

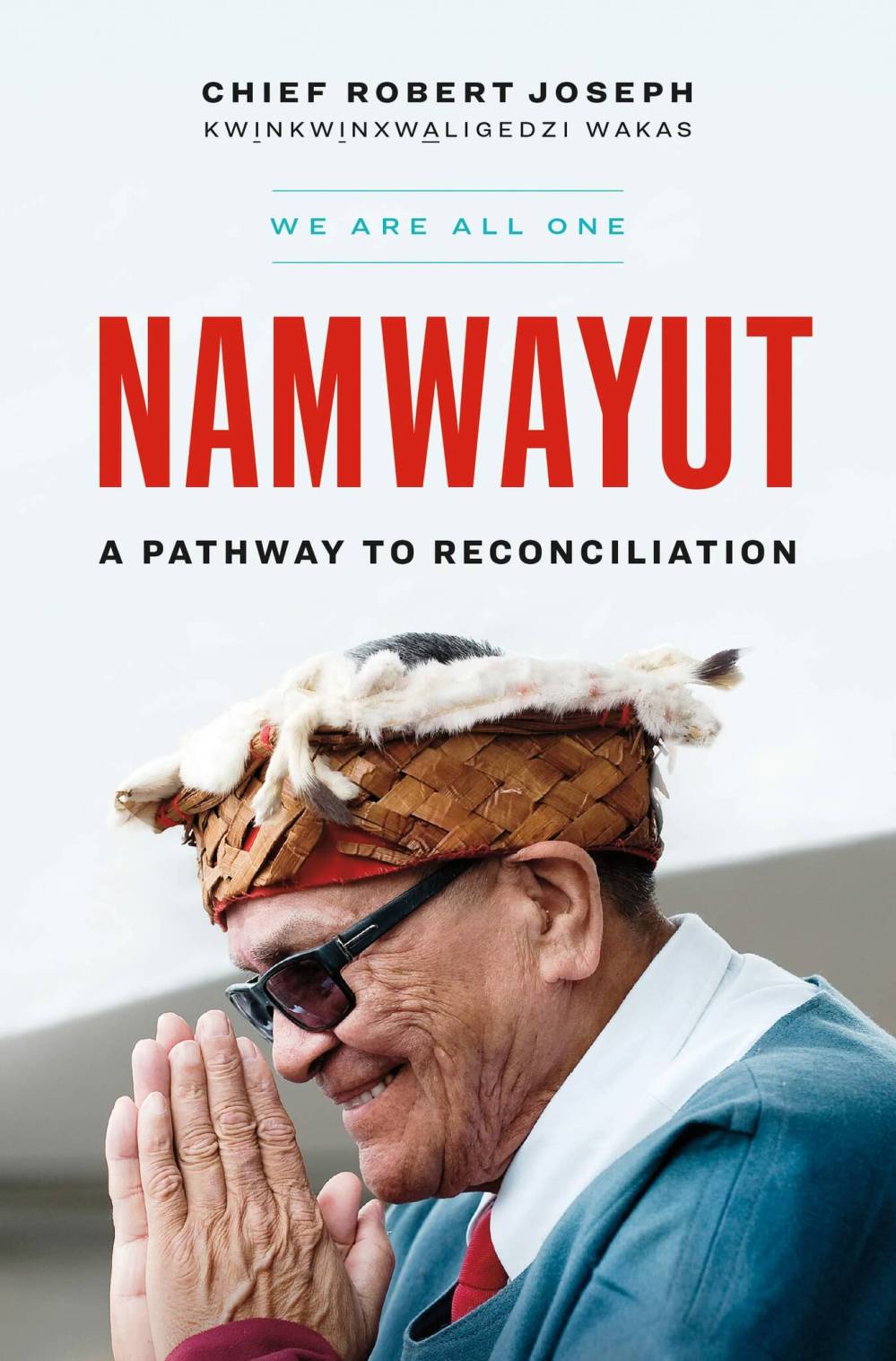

Supplied

Considering his experiences at residential school, the lack of rancour in Chief Robert Joseph’s memoir shows his commitment to reconciliation.

Ten years later, before the announcement of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Chief Joseph told prime minister Stephen Harper to “end in a place of hope.” He describes Harper’s apology as beautiful, including the words, ‘for this we are truly sorry.’”

Chief Joseph’s memoir, subtitled A Pathway to Reconciliation, chronicles his own struggles — with the abuse and damage he suffered at the residential school, and later the ramifications and consequences. But throughout, he brings the reader along on his winding road toward healing.

He holds several honorary doctorates, including in law, from the University of British Columbia and from Vancouver Island University, and in divinity from Vancouver School of Theology. He is an officer of the Order of Canada.

St. Michael’s, where “there was no possible way to learn anything,” succeeded in destroying his self-esteem and made him embarrassed by his culture, resulting in years of broken relationships and alcoholism.

Details of his experiences are jumbled, nightmarish, horrifying and mercifully not the emphasis of the book, although brutal enough to reinforce for readers the overwhelming evil of forced assimilation.

Mostly, he concentrates on efforts to bring himself, other Indigenous peoples and the rest of the residents of Canada — and the world — to feel “our way back into our culture.”

Two formative years when there was a day school in his village allowed him to interact with his primary father figure, Chief Tom Dawson.

“I flourished at the Kingcome Inlet Indian Day School, with high marks in composition… science…and reading, and even an A in arithmetic.”

More importantly, he was connected to his Kwak’wala language and culture through Dawson’s example and teaching, which promoted a “box of treasures” in potlatches.

“Chiefs had possession of these metaphorical boxes in which they collected everything of value: their family’s songs and dances, their prerogatives. Our origin, our place in the universe, togetherness, belonging… flowed from those boxes.”

Namwayut

Namwayut

Joseph continues that leadership tradition at his own potlatches, and as ambassador for peace and reconciliation with the Interreligious and International Federation for World Peace, extending the ideas of togetherness and belonging to Indigenous and immigrants alike.

“We all need to be reconciled to love,” he insists. “Reconciliation should be a virtue, a core value, and it should suffuse the way that we live and breathe.”

Considering the pain and desertion he experienced at St. Michael’s, the lack of rancour in this memoir is a sobering manifestation of Joseph’s commitment to his pathway to reconciliation.

Controversially, he optimistically wrests a “blessing” out of the overwhelming harm. “The Indigenous residential school story may be what will transform this country in galvanizing all of us, together. Canada will be a better country for knowing this story.

“We need each other… Survivors, and all people, need a welcoming, safe, and sacred space to tell our stories.”

Namwayut (We Are All One) is a good place to start, under Chief Robert Joseph’s loving and inclusive leadership.

Bill Rambo teaches at the Laureate Academy on Treaty 1 territory in St. Norbert.