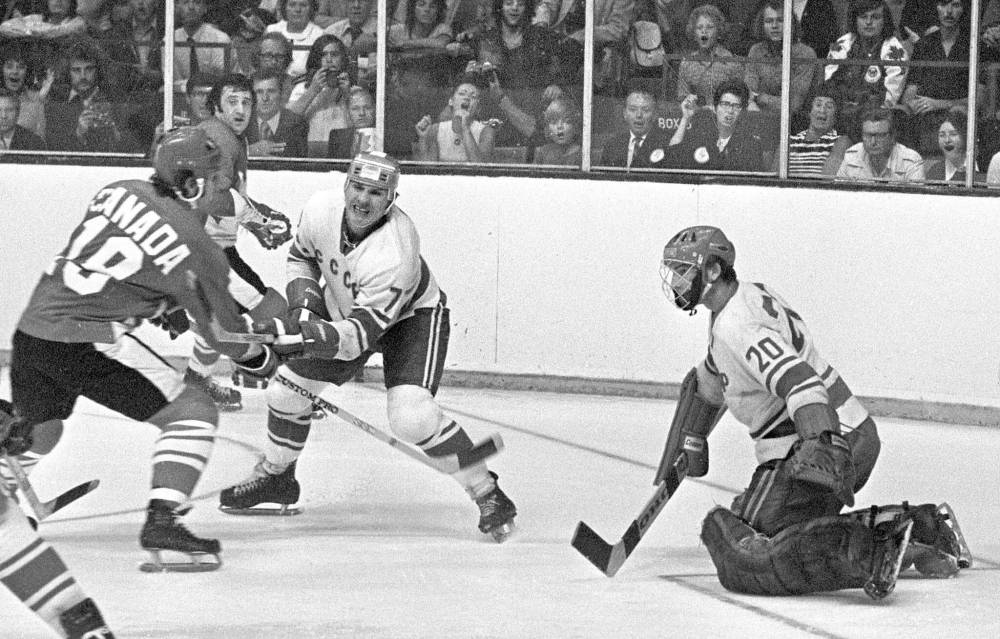

Diplomacy on ice

Former Canadian bureaucrat recalls precarious politics of staging 1972 Summit Series

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/04/2022 (1331 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The 50th anniversary of the 1972 eight-game Canada versus Soviet Union hockey summit series is in September of this year.

Canada won the series on the “goal heard around the world,” scored by Paul Henderson with 34 seconds remaining in the third period of the final game.

When former Canadian diplomat Gary J. Smith started penning this memoir it looked like there might be a half-century celebration of the series, in Moscow.

There was, in fact, a 45th anniversary celebration in Russia in 2017. It was attended by not only a number of players from the victorious Team Canada — Dennis Hull, Frank and Peter Mahovlich, Pat Stapleton, Red Berenson — but also Russian president Vladimir Putin. Smith, by then retired, was one of a handful of Canadian non-players who also attended.

However, any chance of a commemorative celebration vanished when Putin launched his barbaric war against Ukraine earlier this year.

The story of the 1972 Canada-Soviets hockey series has been told before. But it’s never been told from quite this angle.

Smith was a young Russian-speaking Canadian diplomat at the Canadian embassy in Moscow in 1972. (He subsequently rose through the foreign-service ranks, ultimately retiring as Canada’s ambassador to Indonesia.)

And though he was a junior embassy staffer, events conspired to not only give him a front row seat at the Canada-Soviet Union hockey series but to also see him play a major role in making it happen — and then keep it from being derailed.

This is a nuanced and deftly told insider’s account of the early 1970s Cold-War politics that led to an epic hockey series, the original intent of which was to thaw relations between Soviet communism and Western democracy.

Accordingly, the games, and the politics, are relayed through the eyes of a young diplomat who wanted Canada to win, but who even more so wanted the series to build geopolitical bridges.

That optimistic object was put to the test early and often. And became even more dubious when the Soviets came within a hairsbreadth of defeating Team Canada’s collection of NHL stars.

Game Three of the Canadian-sited first half of the series was held in Winnipeg on Sept. 6, 1972, and ended in a 4-4 tie. However, that game in particular was upstaged by other events of the day — the terrorist attack that saw the murder of 11 Israeli athletes, coaches and trainers in Munich’s Olympic village.

Whatever else history records about Vladimir Putin, it must also record him as a hockey cheat and phony.

The 69-year-old Russian president learned to skate and took up hockey less than a decade ago. Yet, somehow, he’s now one of his country’s best players. He scored nine goals in last May’s annual Russian Victory Day hockey game and was named “Man of the Match.”

Smith’s account explains this charade.

He notes the “glowing reports in the Russian media about his goal-scoring prowess. Multiple goals a game.”

But he also reports that when Putin “played with the national or other star-studded teams, the players were advised to ‘part like the Red Sea’ to provide him with an unobstructed path to the net. The goalies were no impediment either.”

Smith remains sanguine about diplomacy’s efficacy, even in the face of Putin’s war against Ukraine.

“Engagement and dialogue remain the foundation of diplomacy,” he writes. “And though diplomacy may falter from time to time, it remains an essential element of foreign policy.”

Maybe so.

But diplomatic negotiations require at least some measure of mutual honesty. And there’s none forthcoming from the Russian president.

Putin’s bald lie about why he invaded Ukraine (to rid the nation of a Nazi regime) is exceeded only by the balder lie of his possessing wondrous hockey skills.

Douglas J. Johnston is a Winnipeg lawyer and writer.