The last laugh

Biographer delves deep into the comedy and the tragedy of Robin Williams' troubled life

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 16/06/2018 (2738 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Whenever I’m asked with whom I’d love to dine, entertainer Robin Williams always tops my short list of three. Still.

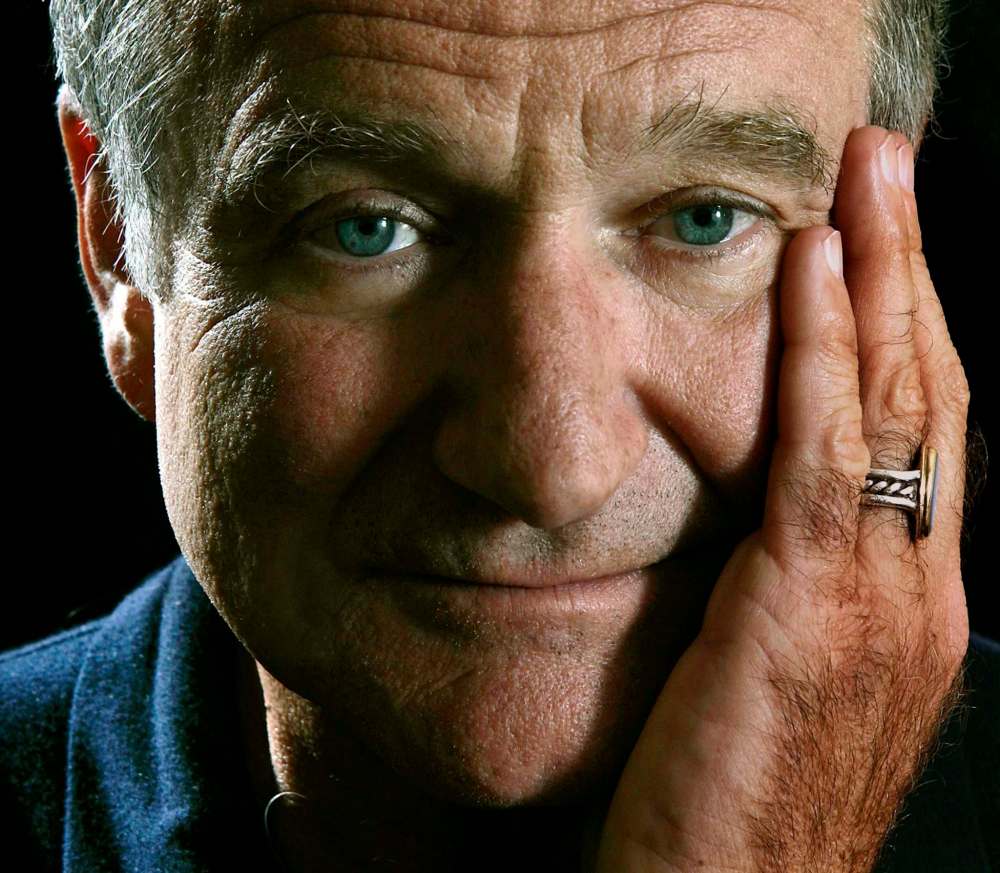

It’s immaterial that we didn’t move in the same social circles. Or that our career paths never crossed, even though one of his many movies, The Big White, was partially shot in Winnipeg in 2005. Something about him — that hairy persona, those kind blue eyes, the “aw shucks” grin — had intrigued me since watching the debut of his Mork & Mindy TV sitcom in 1978. His off-the-wall goofiness simply sealed the deal.

Comedian Williams became movie-star Williams, and I bought every flick — the good, the not-so-good and the real stinkers. His raunchy standup recordings, often released between his movies, were just an added, adult-only bonus.

So I, like many, was gutted when, at age 63, Williams took his own life in 2014. I didn’t “get” it: how could an award-winning, funny guy, admired by so many for so long, get so beaten up inside that he’d off himself?

The recent suicides of designer Kate Spade and chef-turned-cultural explorer Anthony Bourdain haven’t made it any easier to fully grasp the complexities of mental illness.

New York-based author David Itzkoff gives timely perspective on this serious and growing malaise in his recently released biography Robin. Williams and Itzkoff first met in 2009 for a New York Times profile the reporter was working on. Their final confab occurred in 2013 when Itzkoff needed some insight on comedian Billy Crystal, Williams’ longtime pal.

The connection the pair formed in those years eased Williams’ family (a widow, two ex-wives and three now-adult children) into sharing personal tales of woe and warmth for Itzkoff’s biography.

Robin is Itzkoff’s fourth book, and it’s no lightweight read by any definition. Itzkoff’s grasp of the highs and lows of Williams’ outwardly euphoric and sometimes tenuous hold on life comes through loud and clear in these 500-plus pages.

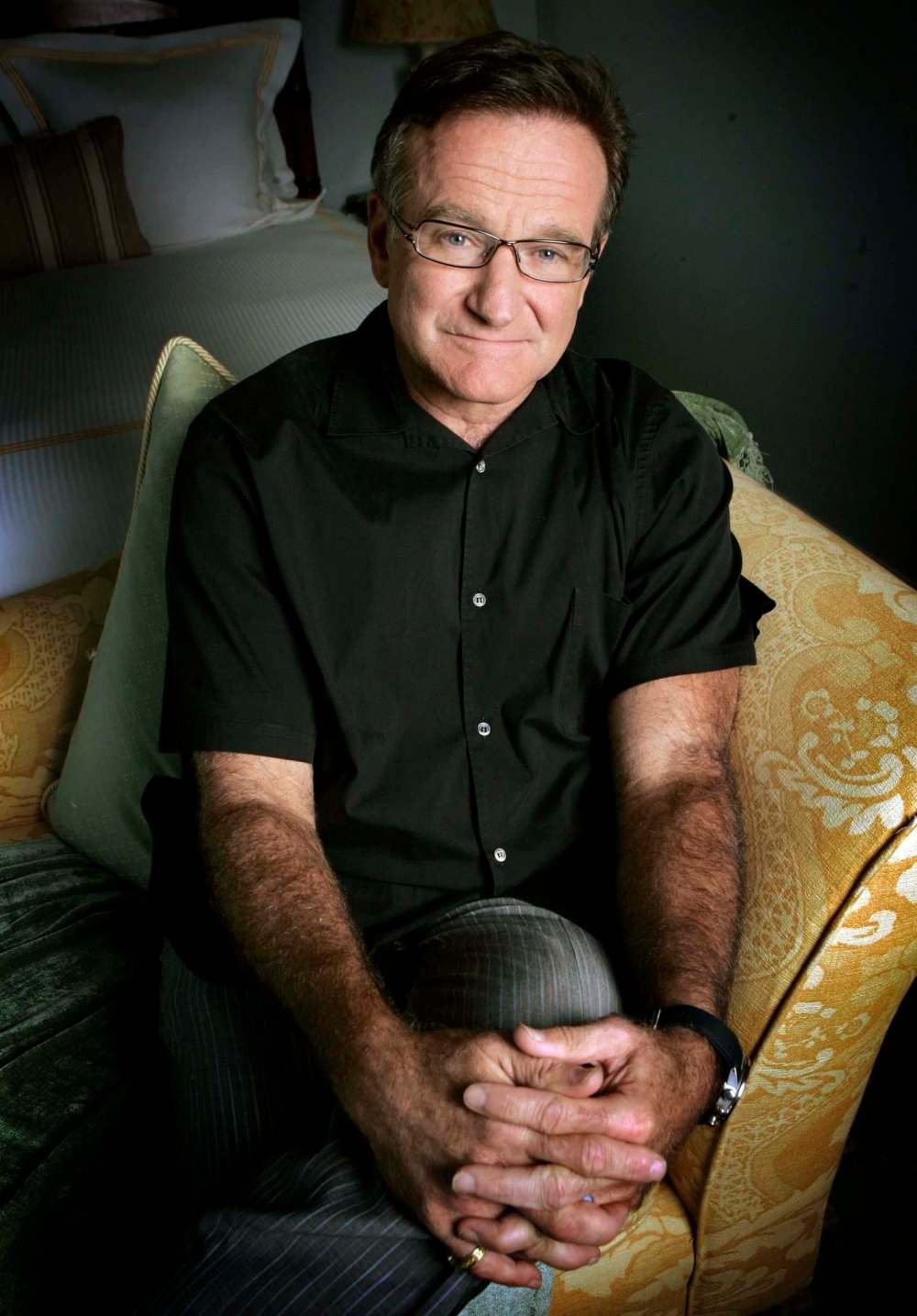

Williams’ rise to stardom was meteoric. He went from the stages of grubby comedy clubs to portraying character actors at New York’s Julliard School to TV’s planet Ork in short order. He started out earning $25 on a good night in the 1970s after a standup gig; near the end of his career he was making $165,000 per episode on the short-lived TV show The Crazy Ones (2013).

He rubbed elbows with showbiz greats, including the late Christopher Reeve, Richard Pryor and Jonathan Winters, a personal idol. Not bad for guy who started his career owning just two pairs of pants and a set of rainbow suspenders.

Yet Itzkoff’s biography also paints a picture of a genuine, kind, tortured soul, who lived, loved and laughed big. Williams’ story — demons and all — warrants this in-depth retelling. Some stories will make you smile; others will clog your throat. It’s a talented biographer that packs that kind of wallop. But then, consider the subject…

‘‘There must be a reason that I am as I am. There must be.’’

Born in Chicago, young Robin McLaurin Williams grew up with no live-in siblings, relying on toy soldiers and TV to amuse himself. After recording televised routines by comedians such as Winters and Jack Parr, Williams would replay the tapes until he had mastered the comic routines, accents and timings. His gift of mimicry made his mother Laurie howl.

As a Ford Motor Company executive, Williams’ dad Rob moved the family often; in an eight-year span, Williams attended six different schools in the Midwest. Fitting in often meant hiding the bits of him that didn’t need sharing with others — a lesson that adult Robin never forgot. When Williams was 16, the family made its last move, to San Francisco.

By the mid-’70s, Williams’ standup reputation was mushrooming. While in Los Angeles, he nabbed the lead role as the affable alien Mork from the planet Ork in a daring new TV show. Mork & Mindy was a cult hit, airing from 1978 to ’82. Friends maintain ABC TV execs “tweaked” the show off the air.

But Williams’ career didn’t falter post-Mork. Quite the opposite — he appeared in more than 60 movies from 1977 to 2014. Some bombed, some were panned and a few were golden, earning him an Oscar (in 1998 for his supporting role in Good Will Hunting), as well as seven Golden Globe awards.

Itzkoff includes an appendix listing Williams’ cinematic and TV appearances, as well as his comedy albums and awards nominations.

“Everyone you meet is fighting a battle you know nothing about. Be kind. Always.’’

Williams’ vices — alcohol, crack, women, not necessarily in that order — were never a secret. But he never let his demons mess with his work; Itzkoff credits Williams’ photographic memory for that. He managed to ditch drugs and alcohol in 1983, staying clean until 2003. Three years later, he returned to rehab.

“Death is nature’s way of saying ‘Your table is ready.’ ”

In the final few months of his life, Williams’ physical, fiscal and emotional health spiralled downward when he began exhibiting Parkinson’s symptoms. The head honchos at CBS cancelled his career reboot, The Crazy Ones. He couldn’t find a punchline anymore. His star had fizzled, and he knew it.

How fortunate, then, that Itzkoff has done such a masterful job of taking Williams’ fans inside the actor’s sad, crazy reality. From Mork and Peter Pan to Dr. Sean Maguire and Euphegenia Doubtfire, Williams’ characters, like the man himself, are beyond memorable.

“Everyone got a piece of him and a fortunate few got quite a lot of him,” writes Itzkoff in the epilogue, “but no one got all of him.”

Shazbot.

GC Cabana-Coldwell is a Winnipeg freelance writer who has now resumed watching old Mork & Mindy episodes on YouTube.