A pointed statement The Winnipeg Art Gallery's angular architecture combines form, function in a building that's both timeless and of its time

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 24/09/2021 (1626 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Asked to talk about the Winnipeg Art Gallery building, Stephen Borys pauses for a moment.

“If I had to describe it in one word, it would be ‘timeless,’” says Borys, current director and CEO of the WAG.

Over the course of the Qaumajuq project, Borys found himself looking at photographs of the original WAG structure, designed by Hong Kong-born Canadian architect Gustavo da Roza, from its 1971 opening right up to the present.

“It’s one of Canada’s significant late modernist buildings,” Borys states. “But you look at these photos, and other than the make of cars and the way people dress, it’s hard to put a date on. And that is something that speaks not just of great architecture. It has a resonance beyond a style or a period.”

Da Roza’s distinctive arrowhead-shaped structure has been a Winnipeg landmark for 50 years. Clad in Manitoba Tyndall limestone, it responds sensitively to the older buildings that surround it. But with a dramatic, dynamic mass that goes right up to the edges of its unusual triangular site, it also seems to challenge them.

The Winnipeg Art Gallery as an institution traces its origins back to 1912, when it was housed in the Board of Trade building and called the Winnipeg Museum of Fine Arts. It later moved into what is now the Manitoba Archives building. It wasn’t until the 1960s — when many ambitious public projects were being funded to mark both Canada’s and Manitoba’s centennial years — that the organization began to plan for a permanent, purpose-built structure. The venture went forward under the stewardship of Austrian-born director Ferdinand Eckhardt.

According to Serena Keshavjee, an associate professor of art history at the University of Winnipeg and editor of Winnipeg Modern, a history of our city’s mid-century architecture, one of Eckhardt’s signal achievements was “to organize and fundraise to build this permanent home for the WAG, which is the elegant, iconic building you’re looking at today.”

“It did help put the WAG on the map as a very important civic museum,” Keshavjee says.

The building’s exterior is big and bold, making it the kind of statement structure that can become a visual symbol for a city.

“It did help put the WAG on the map as a very important civic museum.” – Associate professor Serena Keshavjee

The interior spaces — even though they add up to a whopping 11,000 square metres, or 120,000 square feet — are less assertive, because da Roza didn’t want to compete with the art. As Terri Fuglem suggests, writing in Winnipeg Modern, the interior is characterized by “a quiet monumentality.”

Borys’s favourite space, which he says is also an experience, “is when you come under the entrance canopy, with that series of wonderful lights, and then you move inside.

“At that point of the canopy, it’s a very low ceiling, and then you walk in, and all of a sudden the ceiling goes right up to 21 feet, and you’re in this completely stone-clad hall. You have light coming in, but you don’t know exactly where it’s from,” Borys continues.

“It’s funny, we often install art — big sculptures and paintings — in (Ferdinand Eckhardt Hall). But I actually love it when there’s nothing in it, and it just sings like a piece of art.”

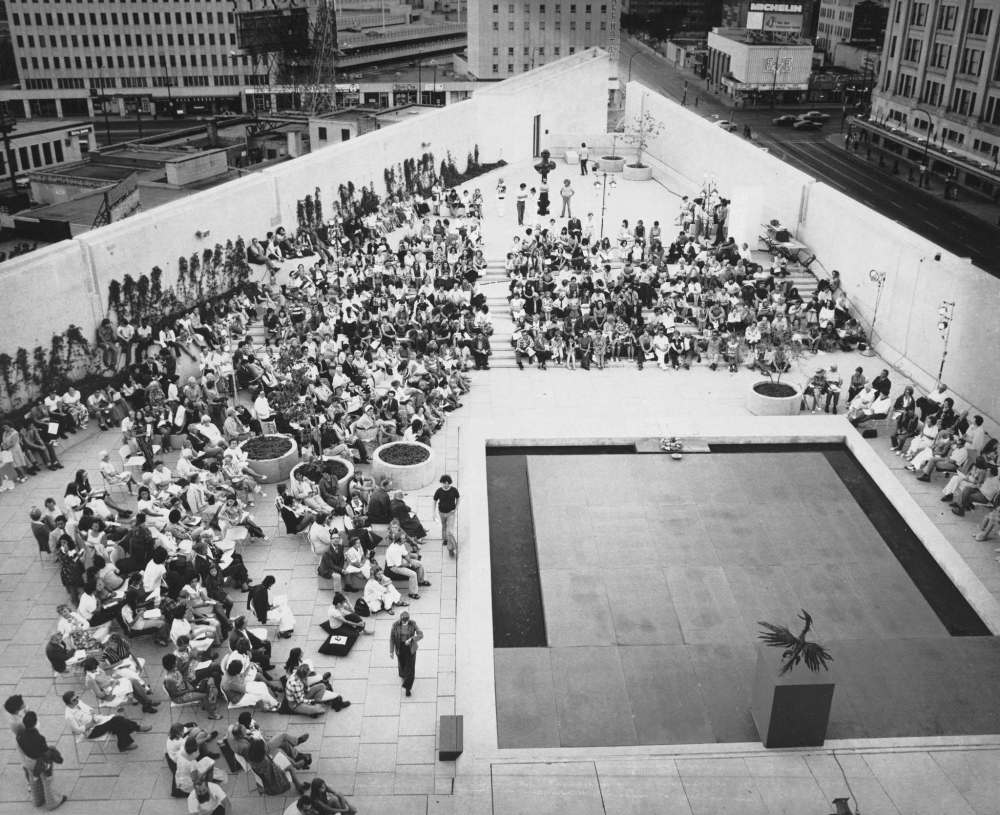

Most visitors are familiar with the building’s public areas — the galleries, which offer a variety of viewing modes, from the hushed, intimate mezzanine spaces to the open, expansive rooms on the third floor; the auditorium, with its sloping walkways and cool swivel chairs; the rooftop sculpture garden, which has hosted many terrific Winnipeg parties.

Like an iceberg, though, the institution has a lot going on out of sight — offices, research areas, storage areas and vaults, and the physical plant that keeps everything running. Form is clearly important in the WAG building — even the chimney is fabulous-looking, more like a sculptural statement than a smokestack — but function is just as crucial.

“I would say this about it, 50 years later, it continues to function, to give, and to work as it was designed and as a modern museum,” Borys says. “Of course, things change, with technology and digitization and different types of media, but overall, the work spaces, the exhibition spaces, the research, conservation and storage spaces remain the way we need them.

“We’ve had upgrades over the years, but the building largely functions as it was designed, without significant changes, and that’s very impressive.”

There has been some controversy, right from the beginning. The building is imposing — for some, perhaps too imposing. According to the Winnipeg Architecture Foundation website, at the time of the WAG’s opening, architect and critic Jonah Lehrman felt the building was elitist, calling it “a retreat for the initiated.”

“Da Roza chose to cover the whole building in Tyndall Stone, for lots of very good reasons,” explains Keshavjee. “It fits in with the other buildings in that area, the Leg and the Bay. And Tyndall Stone tells the natural history of this area, Manitoba, in a beautiful way, and it really makes it a very elegant building.

“But it also makes it into a stone fortress,” Keshavjee adds. “It’s this modernist, minimalist building. There are only a few windows. That entrance is very minimal. All of this has meant that it’s not necessarily an inviting building for the general public. That does, I think, in many ways reflect the elitism of modernism or the avant-garde tradition.

“I love the building,” Keshavjee says, “but I know that it puts some people off.”

“I love the building, but I know that it puts some people off.” – Associate professor Serena Keshavjee

In 1971, when museums were thought of as protectors of cultural artifacts and guardians of a high art tradition, the WAG was of its time. In 2021, however, museums are expected to be more interactive and more accessible.

This new attitude can be seen in Qaumajuq, the new Inuit art centre that connects to the original building. Keshavjee sees an interesting contrast. “We have a new director, Stephen Borys, we have architect Michael Maltzan, and they’re working within this huge cultural shift.

“We’re understanding the importance of public art, the importance of moving away from traditional elitist attitudes towards art. And I’d say that in Treaty 1, we’re working to try to make museums more relevant and to decolonize the museum structure. I think we can see that in the results when you and compare and contrast the two buildings.”

QaumajuQ’s highly visible entrance and big expanses of glass help engage passersby. “You can actually stand on the sidewalk and look in the building and see lots of art for free,” Keshavjee points out.

“I feel like we have two iconic buildings now. The original building reflects 20th-century ideas about art, and this new building is moving us into a new era.”

Borys also sees a meaningful connection between the two structures: “Michael Maltzan respects and understands the Gus da Roza building. It’s much more than a new building next to a 50-year-old building. I believe Michael has found a way to create a new cultural campus with two extraordinary pieces of architecture.

“They both stand out. But there’s an extraordinary and intelligent connectivity between them.”

In 1971, when the WAG building opened, its ship-like prow pointing north, da Roza’s design was seen as radical and new, a fitting symbol of civic confidence and cultural innovation.

A lot has changed since then, in our city and in the art world. Just last weekend, interior design students from the University of Manitoba put together an exhibition in which they completely reconsidered the notion of the museum, in form and philosophy, for the 21st century.

That exhibition was held in Eckhardt Hall.

The WAG building might be turning 50, but that doesn’t mean it’s getting old.

alison.gillmor@freepress.mb.ca

Studying at the University of Winnipeg and later Toronto’s York University, Alison Gillmor planned to become an art historian. She ended up catching the journalism bug when she started as visual arts reviewer at the Winnipeg Free Press in 1992.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.