Walk offers exploration of restorations

First Fridays event to delve into local architectural case studies

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 05/09/2019 (2007 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In April, after the fire at Paris’s Notre Dame Cathedral was finally put out, controversy ignited over how best to respond to the devastating damage.

Experts, architects and ordinary citizens weighed in. Some wanted to rebuild, as closely as possible, the structure as it was. Some suggested an ultra-modern response, while others wanted to leave it as a ruin. As arguments flared, the debate brought into focus the many practical, esthetic and ethical questions surrounding architectural restoration.

At this month’s First Fridays in the Exchange Art Talk/Art Walk, we’ll be speaking with James Wagner, a Winnipeg architect who has worked on heritage projects, and Susan Algie, director of the Winnipeg Architecture Foundation, about case studies in conservation, restoration and adaptive reuse here in our own city. How do big news stories like the Notre Dame connect to our local issues, as Manitobans discuss the fate of the Hudson’s Bay store, the Public Safety Building or the historic mansion currently being fought over on Wellington Crescent?

When it comes to the Notre Dame example, the first question involves the status of the original. “Which ‘original’ are we talking about?” Wagner asks. Notre Dame took almost 200 years to build and then changed over ensuing centuries, including an 1800s restoration that caused its own controversy.

Buildings aren’t static. They can have long and complicated lives. When it comes to a Gothic cathedral, “the vision in mind of the first master builder compared to the master builder three or four generations later doesn’t always align,” Wagner points out. “Things are being adapted and changed.”

We should keep this timeline in mind, Algie believes, when we think about restoration. “It takes a few hundred years to build a cathedral, and then people are trying to make a decision in a couple of weeks.

“With all of these projects, you need that period of thoughtfulness and research. I’m not clear on this need to rush in and make that quick decision on how it’s going to go forward, given that you spent hundreds of years the first time building it up.”

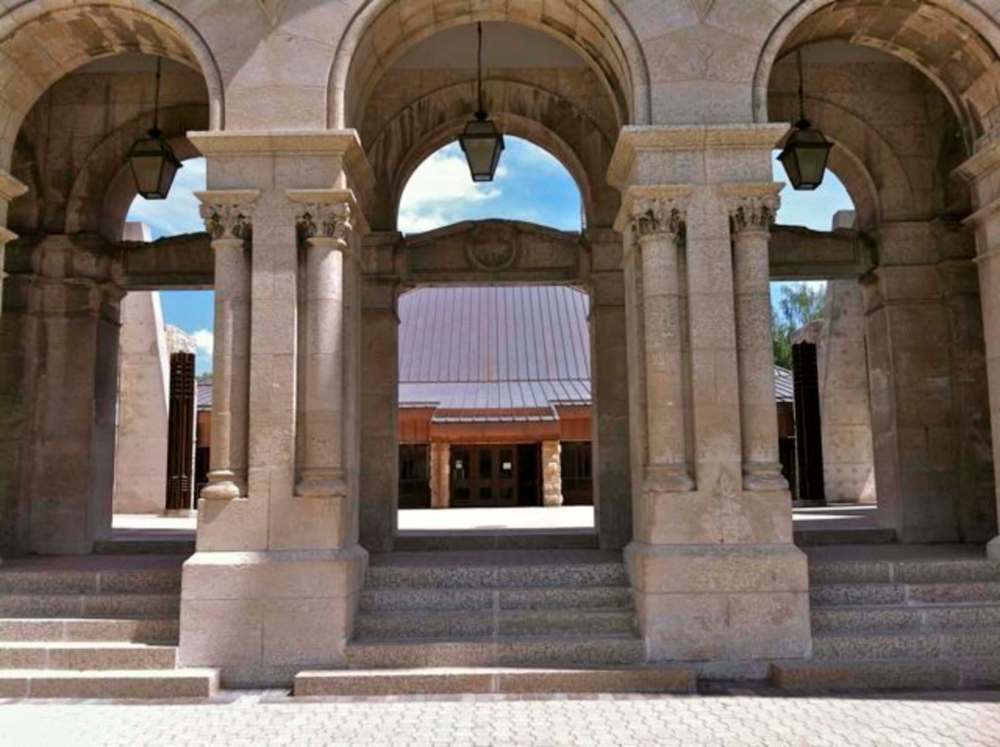

Winnipeg’s own Notre Dame-like situation involved the terrible 1968 fire at the St. Boniface Cathedral. Ultimately, the decision was made to keep the iconic facade, which has taken on an evocative power. Rather than attempting to replicate the rest of the destroyed building, however, architect Étienne Gaboury designed a smaller structure that responded to the old cathedral in a modern way.

A lot of architectural preservation involves the same unexciting, everyday work any homeowner will recognize. Take York Factory, a national historic site that Wagner has been working on. “There’s a lot of ongoing maintenance — painting, repairing windows, fixing the roof,” he says. “It’s kind of unsexy, but it needs to be done.”

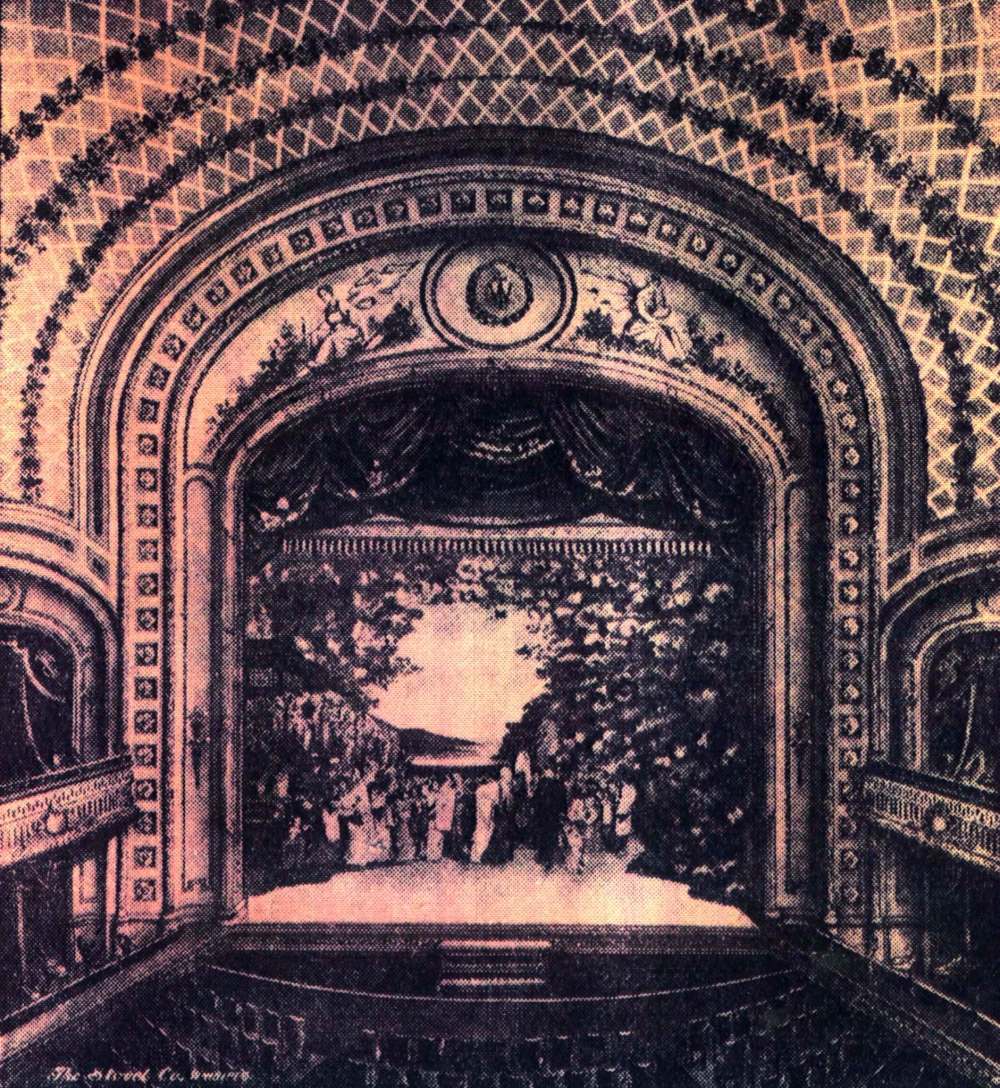

At other times, preservation can take on the glamour of “a detective hunt,” Algie says, citing the Walker Theatre and the 1990s restoration projection that undid its conversion to a movie theatre and recaptured much of its original 1906 beauty. “You need to know the history of it, and the history of what was done to it,” Algie explains. In the case of the Walker, the original drawings provided some guidance, but further information about the decorative scheme was found only at the last minute, in an old newspaper photograph.

While it can be really satisfying to bring back ornamental mouldings or terra cotta panels, sometimes architectural restoration goes in other directions.

You don’t necessarily want what Algie calls “freeze-dried buildings.”

“Most of what we are doing is conservation and rehabilitation,” Algie explains. “Adapting to a new use, meeting all the code requirements, while also keeping the values of the building.”

Algie goes on: “The healthiest building is a building in use. You understand there are going to be adaptations. You want buildings to continue in function, but you want to save the essential things that are important.”

There are practical concerns in adapting older buildings for contemporary use, including issues of safety, energy efficiency and accessibility. People in 2019 might not want a warren of small, separate rooms. They might need more natural light.

Often the materials and the craft skills that defined the original structure aren’t available anymore. (And sometimes for good reason. “We don’t want to restore the authentic asbestos,” Wagner points out.) Modern attempts to replicate the look of historical features, if not done properly, can look flimsy and cheap. When fake brick or fake cornices are pasted on, “the material can look thin, like it’s made of cardboard,” Wagner says.

Often the solution for changes or expansions to older buildings is to respond rather than imitate. This doesn’t always work: star architect Daniel Libeskind’s aggressive 2007 addition to the Royal Ontario Museum, for example, has been widely panned as a disaster. A proposed ultra-modern addition to the stately Chateau Laurier in Ottawa currently has that city mired in conflict and controversy, partly because “Ottawa probably has more architectural historians per square inch than anywhere in the country,” Algie says with a laugh.

To work, contemporary adaptations don’t need to look exactly like the original, but they need to respond meaningfully and respectfully to the original, with scale, proportion and material.

Wagner cites a Dutch architect he knows who divides architectural restorationists into two types: “the curator” and “the alchemist.”

“The curator wants to treat everything with kid gloves and not change anything,” Wagner relates.

“The alchemist asks, ‘What can I create from this structure I’ve been given? How can I keep what is important about this building but adapt it to a new life?’”

This First Fridays’ Art Talk/Art Walk with Susan Algie and James Wagner takes place at the Free Press News Café at 237 McDermot Ave., on Friday, Sept. 6, at 6 p.m., with a guided art tour of the Exchange afterwards. Call 204-421-0682 or email wfpnewscafe@gmail.com to reserve tickets, which include dinner and cost $25 plus tax.

alison.gillmor@freepress.mb.ca

Alison Gillmor

Writer

Studying at the University of Winnipeg and later Toronto’s York University, Alison Gillmor planned to become an art historian. She ended up catching the journalism bug when she started as visual arts reviewer at the Winnipeg Free Press in 1992.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.