Banning books stifles important classroom conversations

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 18/04/2022 (1335 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Who decides what makes a book “harmful”?

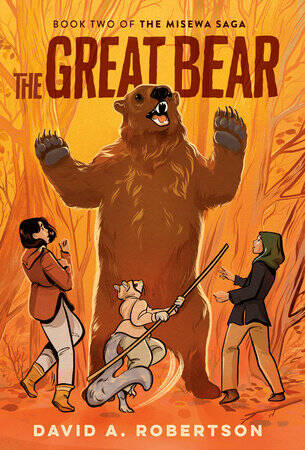

That’s a question being raised by the curious case of the Durham District School Board in Ontario, which has made the baffling decision to ban The Great Bear, a book by David A. Robertson, a Winnipeg-based Swampy Cree author and graphic novelist.

The school board has pulled several books, including Robertson’s, from its school libraries that are, rather euphemistically “under review,” saying they contain “content that could be harmful to Indigenous students and families,” per the Toronto Star.

Anyone who is even a little bit familiar with Robertson’s impressive body of work — which includes the Governor General’s Literary Award-winning When We Were Alone, a children’s book about the legacy of Canada’s residential school system — knows that it has Indigenous students and families at its heart.

Robertson’s work has been targeted before. In 2018, his graphic novel Betty: The Helen Betty Osborne Story, made Alberta Education’s “not-recommended” list for classrooms.

There’s been little clarity around the school board’s decision — including what, exactly, is so “harmful” about The Great Bear, the second instalment in an Indigenous fantasy series aimed at kids 10 and older — but it echoes a broader, disturbing trend playing out south of the border, where a Wyoming county prosecutor’s office considered filing charges against library employees for making LGBTTQ+-themed and sex education available to young people, and a Tennessee school board banned Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel Maus — in which Jews are portrayed as mice and Nazis are portrayed as cats — from a Grade 8 Holocaust unit because of language and a scene of nudity.

“This is disturbing imagery,” Spiegelman told the New York Times. “But you know what? It’s disturbing history.”

Book bannings seem to be driven by a compulsion to shield students from “sensitive subject matter” — a catch-all term that used to encompass sex, violence and language, has now, troublingly, been expanded to include race, gender and cultural identity — because they “aren’t mature enough” or some other flimsy reason.

It’s been a long time since I was a kid/tween, but I can tell you this with certainty: essentially making something contraband — especially, my goodness, a book — won’t make kids less interested in it, and they will absolutely, 100 per cent find a way to see what the big deal is.

But more importantly, literature is an incredibly powerful site for potentially challenging conversations on everything from systemic racism to bullying to sexuality.

There’s a reason reading is frequently likened to a passport: a passport to countless adventures, to paraphrase the author Mary Pope Osborne, a passport to travel back and forward in time, a passport to other worlds — and crucially, a passport to other worldviews.

Literature, especially at such a formative age, can make people feel seen and heard — especially kids whose experiences and identities are often absent from the pages of books.

Literature can build empathy, insight, curiosity and understanding. If you only ever see stories that closely resemble your own reflected back at you, how do you learn and grow? Reading books from a wide variety of perspectives, telling a wide variety of stories that reflect the breadth of humanity — good and bad — allows us to interrogate our biases, be exposed to new ideas, see things from different angles. In books, we can better understand ourselves and each other.

And there’s no better place to do all that than in school, where there’s infrastructure in place to have discussions, ask questions, and write down thoughts and impressions.

Like many Manitoban students of a certain age, I read April Raintree by Beatrice Culleton Mosionier — the CanLit classic about two Métis sisters who are separated and placed in different foster homes — when I was in school. I can’t remember what grade I was in, only that I was young, barely a teenager. A harrowing scene in which April is raped left a searing impression on me — the violence of it, the language of it, the racism and brutality of it, all conveyed in spare, unflinching prose. (I located the passage while writing this column and was unsurprised to see that I’d remembered it vividly, nearly word for word.) April Raintree is a YA novel.

It’s worth noting that April Raintree was, when it was first published in 1983 as In Search of April Raintree, intended for adults — specifically Métis women. Mosionier revised the book a little, slightly toning down some language and the rape scene, so that it could make it into schools; it was an important story that needed to be taught. But notice that the book wasn’t banned; the author was the one to drive small changes that would help get her words to a wider audience.

April Raintree wasn’t an easy read — then or now. But I am better for having read it. It put into context, clearly, the violence and objectification experienced by too many Indigenous women, too often.

Because that’s just it: the things that happen to people in books also happen to people in real life — including to young people. Not reading about or discussing things that matter — in their full complexity — does a disservice to everyone, but especially young readers who are, so often, woefully underestimated.

We need more books like The Great Bear, like April Raintree — not fewer. As Robertson himself tweeted: “When I was a kid, I needed a book like The Great Bear. I didn’t have it. It’s there now. Don’t take it away.”

jen.zoratti@winnipegfreepress.com

Twitter: @JenZoratti

Jen Zoratti is a Winnipeg Free Press columnist and author of the newsletter, NEXT, a weekly look towards a post-pandemic future.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.