Reconstruction zone

Bright orange safety shirts usually serve as a warning, but thanks to a young designer, they're also a beacon of hope

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/09/2021 (1539 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It’s noon, and 19-year-old Isaiah Binns is running a bit late.

Binns, who graduated last spring from Elmwood High School, is supposed to arrive at the downtown headquarters of Richlu Industries, the manufacturer of Tough Duck workwear, to see the logo he helped create for a line of the company’s reflective safety clothing ahead of the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation. Waiting in the room are Matthew Reis, who was his former high school graphic design teacher, and a trio of Tough Duck employees.

“You know how teenagers can be,” Reis says. “But he’s on his way.”

Soon, in walks the man of the hour, shuffling his Vans sneakers into the boardroom and saying hello, feeling a little bit nervous to see his logo in person and a touch overwhelmed by all the attention. He didn’t exactly expect to be here.

“I just wanted my class credit,” he says with a laugh.

Last year, Binns was struggling to pass graphic design, not for a lack of talent, but for an admitted deficit in effort and a difficult year personally, something not uncommon for high school seniors, especially amid a pandemic. “My dad was on my case,” he says, as was Reis, who saw some of his student’s writing and knew he had more to give.

Feeling the pinch, Binns got to work, eventually finishing a piece of art for his semester’s project that Reis described as a standout: two hands, cradling the earth, along with an eagle and a yellow sun, seven feathers, and the following words: “War is not the answer, for only love can conquer hate. Everybody thinks we’re wrong but who are they to judge us simply because our hair is long.”

The work revealed Binns’ visual and poetic talent, and gave the football star an outlet to showcase his Indigenous identity, rooted in Canupawakpa Dakota First Nation. Binns was also honoured with a Manitoba Indigenous Youth Achievement Award. Just as important to him, he got his course credit.

So he graduated, putting graphic art and Reis’s class behind him. Or so he thought.

Early in the summer, as revelations about the brutality and genocidal truths of the residential school system were being made — fuelled by the discovery of unmarked graves at former school sites across the country — Tough Duck’s Bob Axelrod, the merchandiser for the company’s reflective safety gear, got reflective himself.

“I started to read more, and what I found really rattled me,” says Axelrod, who as a Jewish person had learned a good deal about the Holocaust but not about the atrocities committed in his own country. “I realized the scar on this country, and I was completely ignorant of it to that point. I didn’t even realize I drove past a residential school (the former Assiniboia Residential School) every day down Academy Road.”

Like many Canadians, Axelrod was struck with guilt and anger. And as people began wearing orange shirts to show solidarity with Indigenous communities, proclaiming that every child matters, Axelrod had a simple realization: his company makes thousands of orange shirts every week. “When we sell personal protective equipment, it’s really about luminosity and chromaticity, and being able to see it at a distance,” explains Axelrod. “One of the best colours for that is orange.”

He wondered, could they add a graphic design to make the clothing reflective in more ways than one?

So he asked a co-worker if he could recommend an Indigenous artist, and a relative of that co-worker suggested a young man from Elmwood High School.

On a sweltering 35 C day in July, Axelrod met Binns in a Subway parking lot, struck by his stoic nature and contemplative attitude. “I said, ‘Take a few weeks, come up with a design, and we’ll give you full credit,’” Axelrod recalls. “Isaiah asks, ‘What do you want?’ and I said, ‘I don’t want to tell you what I want. I want to see what you come up with. I’m excited to see where you go with it.’”

Needing a bit of direction, Binns went to Reis, whose class he used to skip, for guidance. “It was very cool because this is what I’d assign them in class,” Reis says. “A client needs art, and it’s up to you to make it for them.”

Binns himself says the uncovering of bodies angered him deeply, and revealed the “evil roots” of the country, fuelling a desire to educate those around him to love each other instead of hate with his design and actions.”Dawg, if only the whole world could come together,” he said.

A few weeks passed, and Binns and Reis returned to Axelrod with 12 design variations, giving the client options for which to put on its long-sleeved orange T-shirts, to be given, free, to worthy community organizations, with future plans for the logo still in the works. The company does not want any profits from the design. Axelrod’s eyes widened at one design in particular, and the trio arranged to meet as the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, Sept. 30, neared to reveal the logo to the artist and his mentor.

When Binns arrived at Tough Duck headquarters, Axelrod couldn’t wait to show the final product to the young man, who has clothing-industry aspirations himself.

He pulled out two quilted jackets, custom-made for Binns and Reis, and flipped the sleeve to show Binns’ design on the shoulder, which quaintly and powerfully united both the message of reconciliation with the Tough Duck brand. Reis was sitting nearby, kvelling.

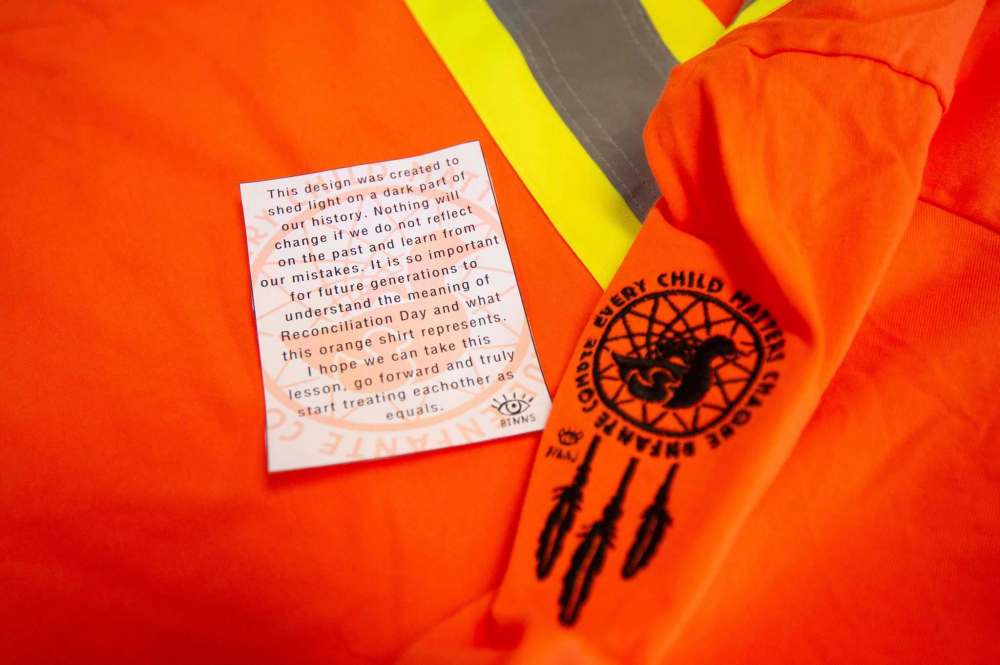

The logo Binns created features a mother duck and duckling, swimming side by side at the centre of a dream catcher, surrounded by the words “Every child matters. Chaque enfant compte.”

“That is dope,” Binns said.

He slipped the jacket on. A bit tight, but Axelrod said they could get him a bigger size, no problem. Then, he and Reis donned the orange shirts, stepping out onto Adelaide Street to get a better look.

Binns was in disbelief. Less than a year ago he’d been struggling to make it to class — a “ninja,” according to Reis — and now he had some validation of his talents. Plus, his work raised awareness for a cause close to his heart, and helped him connect with his culture, something he’s been trying to do since his mother died when he was 15.

As part of his design work, Binns also wrote the text for the shirt tags, displaying wisdom beyond his age.

“This design was created to shed light on a dark part of our history. Nothing will change if we do not reflect on the past and learn from our mistakes. It is so important for future generations to understand the meaning of Reconciliation Day and what this orange shirt represents. I hope we can take this lesson, go forward and truly start treating each other as equals.”

In his application for the achievement award, he shared more wisdom. “As Indigenous people, the odds are against us, but we cannot let it take us. We were born warriors and survivors of the land beneath us,” he wrote. “Follow your heart, block out all the negativity and remove it. Don’t listen to anyone who thinks differently of you. Don’t embrace the hate or you will become a part of that negative outlook. At the end of the day, we are the artists of our own world and we get to paint whatever picture we want, in any colour, even if it appears ugly to everyone else. It is ours. As long as we find beauty in what we’re painting, we will be smiling and that, is worth it.”

Standing on Adelaide Street, he was smiling. Everybody was.

ben.waldman@freepress.mb.ca

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.