Domestic-violence brain injuries a ‘hidden epidemic’

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for four weeks then billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 08/01/2023 (716 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Most of what we know about traumatic brain injuries comes from the experiences and injuries of male professional athletes.

But debilitating traumatic brain injuries aren’t just sustained on the field or rink. They are also being inflicted on women at the hands of intimate partners.

A report in the Globe and Mail revealed one in eight Canadian women are likely suffering from a brain injury related to domestic violence (DV). That works out to about 4,500 women for every NHL player, according to Halina Haag, a researcher advocating for more study into how domestic violence affects women’s brains.

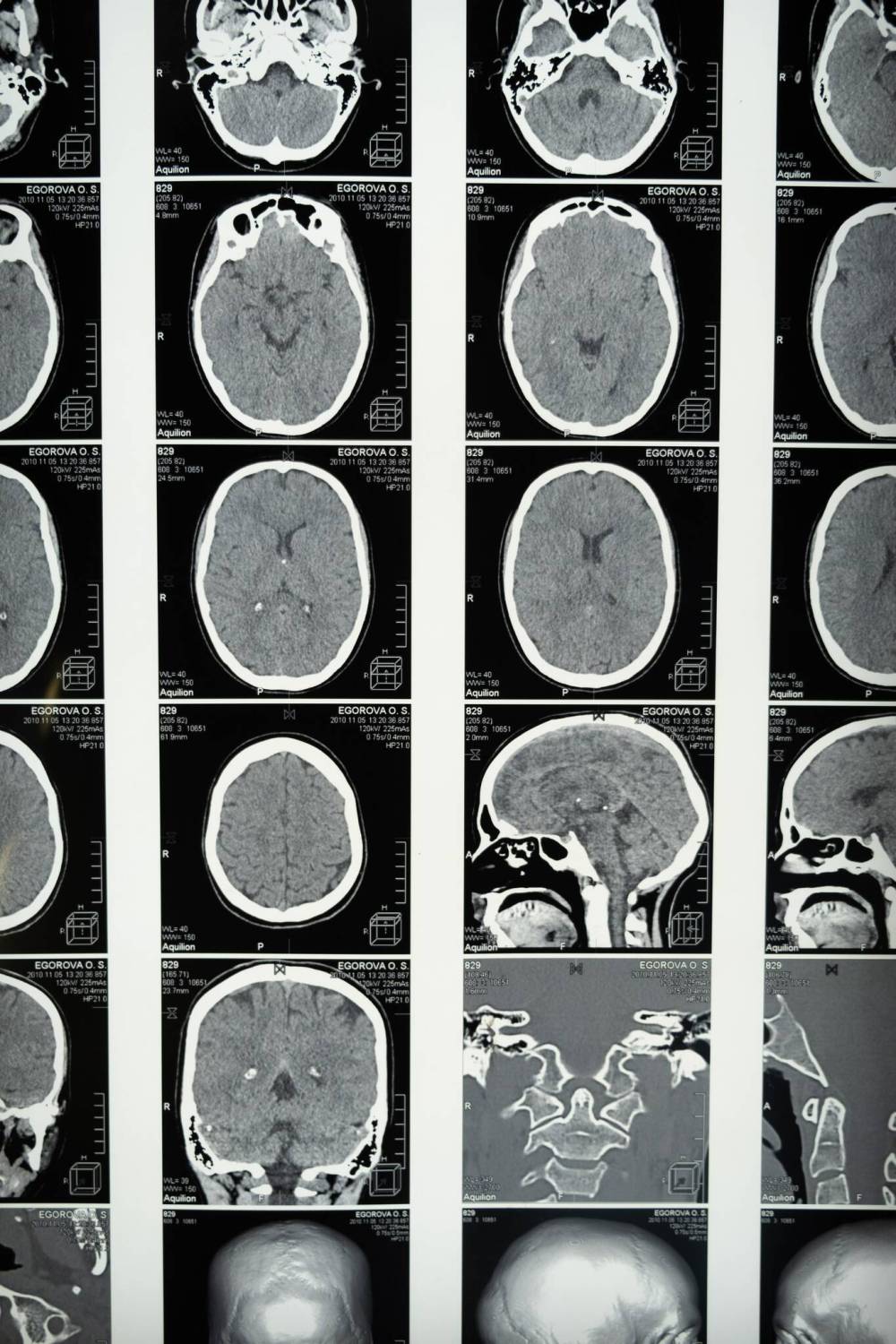

PEXELS IMAGE

More study is need on brain injuries related to domestic violence.

It’s estimated hits to the head, face and neck account for more than 90 per cent of physical abuse, according to University of Toronto researcher Angela Colantonio, which increases the risk of brain injury. But because visible injuries such as broken bones and contusions are more closely associated with domestic violence than concussions, women who do seek medical treatment for DV-related injuries may not be receiving proper diagnoses or treatment.

That puts them at risk for permanent brain injury and disability. Many women may not be aware they even have a brain injury from repetitive trauma.

Researchers also don’t have a full picture of how DV affects women’s brains. The intersection between traumatic brain injury and domestic violence is an important area of study — and a very challenging one. It requires the study of victims’ brains and, according to the Globe and Mail, “nearly all of the brains available for concussion research in Canada currently are from male athletes.”

Post-mortem examinations of athletes’ brains have led to important breakthroughs, such as the confirmation that repetitive brain trauma — even the kind characterized as mild — can lead to chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE. A 2017 study examined the brains of 202 former football players and found CTE in nearly 90 per cent.

But, for a host of ethical and logistical reasons, there is not the same kind of access to the brains of deceased women who either experienced DV or were murdered by their partners, which means CTE-style breakthroughs for living women who are navigating confusion, personality changes, memory loss and other symptoms are far off.

The U.S. organization Pink Concussions is asking women who have suffered DV (as well as sustained head injuries in sport or while serving in the military) to pledge their brains to science after they die so a more robust brain bank can be built.

In recent years, Canada has seen a gradual but steady increase in domestic violence in what many researchers and advocates are calling a “shadow pandemic.” COVID-19 restrictions and lockdowns led to an increase in isolation and stress; it turns out “now is the time to stay home” is only healthy advice if your home is actually safe.

According to Statistics Canada, police reported 114,132 victims of intimate partner violence in 2021, making it the seventh consecutive year in which this type of violence has increased. Eight in 10 victims were women and girls. These are police-reported victims; because many victims of domestic violence don’t report it to the police, the actual rate is likely much higher.

In 2021, 90 homicide victims were killed by an intimate partner. Seventy six per cent of these victims were women and girls. That number is also up from years previous.

Brain injuries from domestic violence have long been called a hidden epidemic. It’s clear this health emergency needs more public awareness, more research and, crucially, more funding. If the long-term physiological impacts of domestic violence were better studied and better understood, fewer women would have to suffer in silence.