Raising their voices

Belcourt’s innovative novel offers a literary reckoning for the dispossessed

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/01/2023 (1067 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

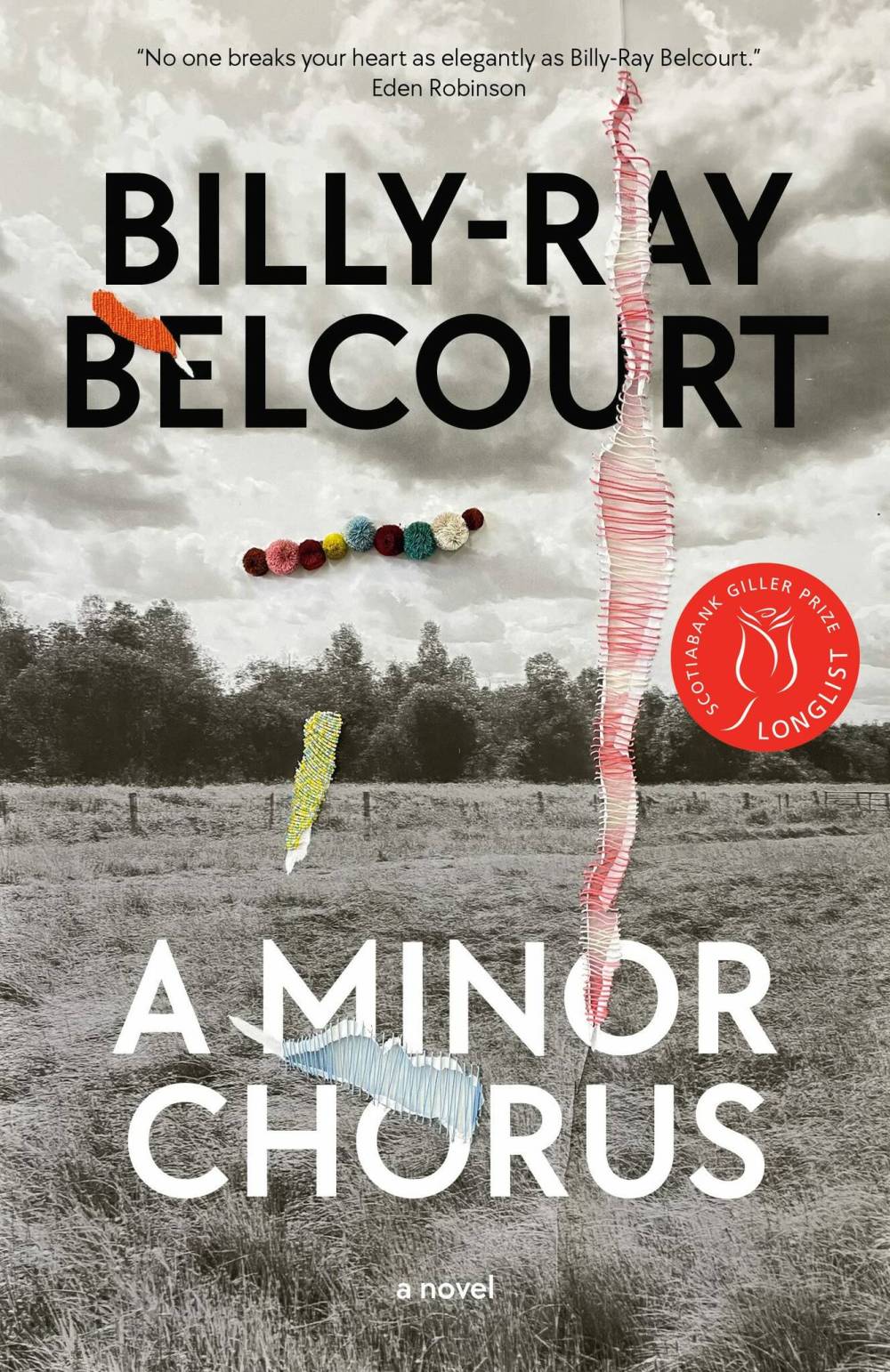

Billy-Ray Belcourt’s fourth book and first novel A Minor Chorus is a spare, urgent, beautifully written autobiography of a hometown that uses a blend of forms to turn novel-writing in and of itself into a radical act attuned to decolonization, grief and love.

Named among the best books of 2022 by the Globe and Mail, Indigo and CBC, A Minor Chorus follows closely on the heels of Belcourt’s award-winning memoir, A History of My Brief Body, as well as two collections of poetry: his Griffin Prize-winning debut This Wound Is a World and NDN Coping Mechanisms: Notes from the Field.

In A Minor Chorus, an unnamed narrator, “born into a so-called margin,” abandons his PhD to become a novelist and journeys to his home community in northern Alberta, crossing over from Treaty 6 to Treaty 8 territory, “an old but not ancient division,” to interview various members of the place he left years ago.

Jaye Simpson photo

Author Billly-Ray Belcourt

(Belcourt, himself a renowned writer and academic, is from Driftpile Cree Nation and is assistant professor in the School of Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia.)

Before setting out, the narrator meets dear friend River, who has a knack for looking “effortlessly queer” and is a grounding presence throughout the novel. River’s research combats misknowing within the academy; they plan to return to their rez after grad school so that youth don’t have to leave to learn about politics and history.

There is also Hannah, the empathetic, charismatic professor who “could only say so much on behalf of an institution she herself was skeptical of;” and Graham, pronounced Grhm, a Grindr hookup portrayed through seamless shifts between poetry and prose.

The narrator’s arrival in northern Alberta is accompanied by elegant, crushing descriptions that no settler should go without hearing: “Behind the dilapidating building ran train tracks that were less like sutures and more like wounds. It all looked so ordinary and Canadian and, because of this, haunted.”

During the interviews, an auntie tells stories of men on the reserve being “stalked and ignored at the same time” and of the systemically unjust incarceration of her grandson; Michael speaks of his first and only love in a generation that viewed homosexuality as a crime. Cousin Lena can’t wait to read the novel-in-progress, and uses the pronouns “I” and “we” interchangeably: “Lena, on account of having been on the rez her whole life, could marshal this collective voice.”

It is this collective voice that becomes a minor chorus, which builds as the interviews unfold, driven by the narrator’s instinct that “the disregarded sometimes live the most remarkable lives” and concludes with an exquisite crescendo honouring one such life.

Many novelists, activists and theorists are cited and spun throughout the novel along with the voices of those interviewed. Grief and laughter take turns, coincide, as when the narrator speaks to his Auntie Donna, who raised him when his mother could not: “We laughed deeply and Creely, the sort that makes the world feel at least marginally more habitable.”

A Minor Chorus

When a pivotal interview transpires at a state-of-the-art remand centre — “a twenty-first-century creation where a nineteenth- and twentieth-century hatred of Indigenous peoples ran rampant” — there is an historic and literary reckoning to behold.

A Minor Chorus is that rare thing: a novel that reinvents the form to create and to say something crucial and new.

Sara Harms will forever associate any mention of Leonardo DiCaprio with the poem Leonardo DiCaprio from Belcourt’s NDN Coping Mechanisms: Notes from the Field.