Everybody Loves Roman A profile of one of Winnipeg’s worst-kept secret singer/songwriters

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 08/12/2022 (1106 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Roman Clarke lives in the last house on his street, with the silently shimmering Seine River as his next-door neighbour. Seated at the picnic table in his backyard are knee-high piles of snow. In the window sill by the front door rests a can of Labatt Blue, the leftover sips frozen by the mid-November chill.

His living room is saturated with ephemera. Little sculptures of puppy dogs occupy his bookshelf. Clippings from a pothos plant propagate in a bottle once filled with Coca-Cola. In one corner, next to an upright piano, stands an acoustic guitar begging to be plucked. The toilet is in the shower — yes, the toilet is in the shower, giving a new definition to two-in-one. The things you put up with when you find a good rental in Winnipeg.

Bathroom hybrids aside, this is the home of an average 26-year-old man.

“I got this at the MCC,” Clarke says with pride, rubbing his hand across his yellow couch, covered by embossed flora. “Most of this stuff is from the MCC.”

JESSICA LEE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Roman Clarke is one of only a handful of musicians to perfect the art of singing while playing drums.

But Clarke, despite his easy-going, go-with-the-flow, lust-for-life aura, is not like most other 26-year-old men in Winnipeg. As a 27-year-old man in this city, I can attest to that. I also have ephemera here and there. I also have an acoustic guitar. I also have had plant clippings propagating inside old bottles on my window sills. Clarke, whose parents nearly named him Romeo, has something else, something entirely different.

An otherworldly voice. An uncanny ear for melody and harmony. A coolness and humility that is pure and natural. An effervescent sense of self. An unmistakable joy, and a willingness to help his friends and share himself with others.

Clarke, who just released his long-awaited album, I Think It’s All A Dream, seems to be allergic to the expectations others impose on him as an artist and, for lack of a better word, a star. A frequent comment made about Clarke, who has quietly been a loud voice in the Manitoba music world since he was a teenager, is that he should be bigger. He should be selling out bigger venues. He should have more monthly listeners on streaming services. He should do this, and he shouldn’t do that.

“I’ve heard that a lot,” he says. “Should be bigger. And there was a point in time when I started to believe that.”

That feeling hit an apex after the release of Clarke’s 2019 album, Scorcher, a soulful set of 11 songs that found a passionate listenership hanging on for dear life to every impassioned lyric. It was funky. It was loose. And it announced to whoever was listening Clarke’s capabilities as a musician, a singer, a performer, a songwriter, and a producer.

An otherworldly voice. An uncanny ear for melody and harmony. A coolness and humility that is pure and natural. An effervescent sense of self.

But what happened next was not the expected course of action. “It was the exact opposite of what I probably should have done,” laughs Clarke, who has a stud shaped like a star poking out of his nostril. He pulled the album from streaming services. Poof. Gone. Long-time listeners typed in Scorcher and nothing came up. What? How? Why?

“I would say that my reasons were valid,” he says.

“I think that whole process really exemplified how I want to grow. At the time, I wanted to be able to make something and have the next thing be so much better, or completely revolutionary for me. I feel like my learning curve for music has always been so fast. I’ve always learned things extremely quickly, and I’ve always improved super quickly, so it’s easy for me to do one thing, and think it’s the best thing I’ve ever made, and then literally three days later, I’ll learn something and improve the process and either make a different version or new song. And all of a sudden, my experience with the original doesn’t even matter anymore. I want to improve.”

“Scorcher was the epitome of everything I had learned up to that point, and a year later, I didn’t think it meant anything to me anymore. I wanted to try representing myself as an artist in a completely different way, and I think that’s totally fair.”

But then, midway through the pandemic, he started to go out in public again. At his friends’ shows and at coffee shops, and even when he was walking on the street, people would stop him.

JESSICA LEE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Clarke used his backyard studio to record his latest album, I think It’s All a Dream.

“I could not show my face in Winnipeg without someone asking me, ‘Dude, where’s your album?’” Clarke says.

So he gave the people what they wanted, and put the album back online, because Roman Clarke is a man of the people. His fans have high expectations of him to provide fun, funk, and nonstop joyful earworms.

Clarke — who used to play in the 2010s indie pop band The Middle Coast, alongside Dylan MacDonald (aka Field Guide) and Liam Duncan (aka Boy Golden) — has over the past decade accrued a loyal fan base waiting on his every riff. “I may have only three to 4,000 followers on Spotify, but I don’t care to have hundreds of thousands,” he says with sincerity. “No disrespect to those who have reached that level — that’s amazing and wonderful and so, so great — but I feel that the bottom line is I am going to do exactly what I’m going to do.”

When Clarke performs, he does one of the coolest things an artist can do, which is to drum and sing at the same time. It’s counterintuitive: the drum forms the rhythmic backbone of most popular music, establishing a framework for other instruments, including the human voice, to branch from, working in and over time to create bursts of opportunity for other bandmates to shine. It’s hard to say as a non-drummer what makes any percussionist a great one, but it’s not hard to see it when you watch a great drummer in person. It’s the feeling of control, and of trust, that with the sticks held by the proper hands, the music will both resist and engage with the pulls of entropy and logic to remain in an order that remains both expected and surprising.

That’s how it feels to watch Clarke drum and sing at the same time. It’s an extremely difficult task, rarely attempted or perfected, with performers including Karen Carpenter, Phil Collins, and one of Clarke’s idols, Anderson Paak, pulling off the balancing act.

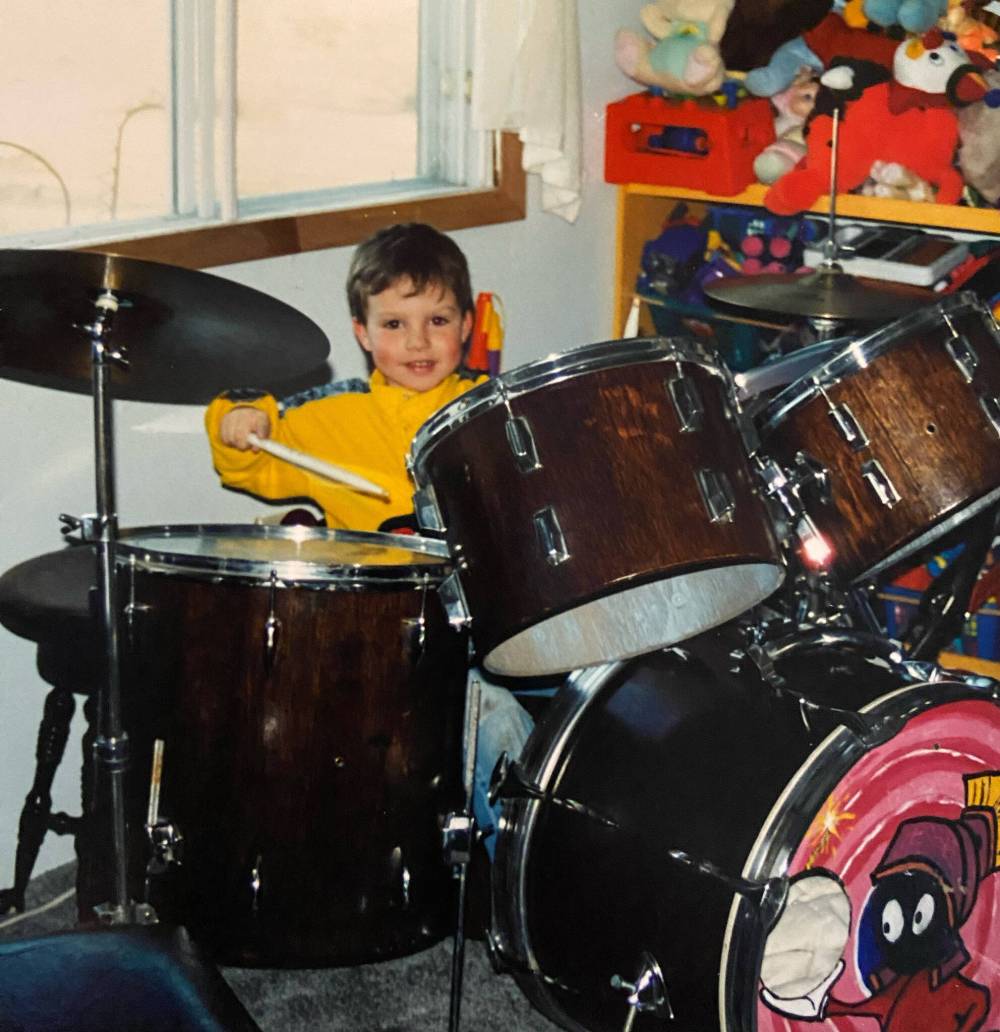

Clarke started out on a different instrument entirely: the violin. His father, Cary, played in several bands, including one called Marvin, and another called Filthy Lucre, in and around Brandon, where Clarke was born and raised. Roman tagged along to band practice shortly after he started walking, and pretty quickly, he showed not just an affinity, but a proclivity, for rhythm. Cary and others taught his son the bass, the guitar, the piano, and whatever else was around.

In Filthy Lucre, there was a fiddle player named Fred, and Clarke was in love with the sounds of those strings. “I wanted to play like Fred,” he recalls.

JESSICA LEE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Clarke, who also plays guitar and piano, started by learning the violin, but the Suzuki method of teaching wasn’t for him, so he moved to drums.

He started taking lessons, but they weren’t the free-wheeling style of his dad’s band. They were of the Suzuki methodology. “I said, ‘What is this garbage?’” He looked elsewhere in Filthy Lucre for inspiration, and his eyes focused behind the kit of Paul Roozendahl, the band’s drummer. There. That. He wanted to do that.

“Not unless you practice your violin,” his parents said. But it was pretty clear their son would not be limited to one instrument. He didn’t want to be put in a box.

He had aspirations to venture even further afield. As teenagers, he and his sister moved to Winnipeg, where they rented a spot on Sherbrook Street. “That was about as ‘city’ as a couple of country bumpkins could get,” says Clarke. “We grew up in the country, and we did all the country-ass shit.”

In the city, with Duncan and MacDonald, who Clarke had been playing with in a group called Until Red, the drummer explored Winnipeg’s music venues. The trio became enamoured with a band of brothers, and the respect was mutual.

“I don’t remember exactly the first time we crossed paths, but it was probably around 2013 or 2014,” says David Landreth, of the Juno-winning The Bros Landreth. “(Until Red) were fans of our band and we saw them at a ton of shows early on. The first time we heard them live, we were all knocked out. They were frighteningly capable musicians and great singers. It was immediately obvious that these guys were going to be staples on the scene and the vanguard of the next generation of artists coming out of Manitoba.”

“I checked out a few of his (Roman Clarke) demos, and was kind of floored… I don’t like comparing people, but he was giving me a Remy Shand vibe.”–Ariel Posen, guitarist

Ariel Posen, a Winnipeg-raised guitarist who is considered by some as one of the best players on the continent, was with the Bros. at the time. “I remember being on tour, somewhere in the states, Bloomington, Indiana or somewhere in Illinois, and a friend of mine from Brandon asked: have you heard Roman’s solo stuff yet?”

Posen hadn’t. That changed. “I checked out a few of his demos, and was kind of floored,” he says. He sent Clarke a message: we should write together some time. If you need any help with guitar, let me know.

Clarke took Posen up on the offer, and the guitarist, 10 years Clarke’s senior, was again, shocked. “He would send me a song a week, sometimes two,” he recalls. “While this was all happening, I was so dumbfounded. I don’t like comparing people, but he was giving me a Remy Shand vibe. Not necessarily in terms of how he sounded, but he was also a one-man band who was super musical, totally got it, could record everything himself.”

“I started showing (Clarke’s music) to other people, and I am not taking any credit here, but I said, ‘You have to hear this. You are not going to believe this.’”

SUPPLIED Clarke learned to play drums as a child.

Posen’s respect for Clarke was so high that he demo’d every song with him before Posen’s first record was produced. Clarke even co-wrote several of Posen’s favourite songs.

“People knew he was great, but I don’t think understood how great.”

Fast forward to 2021, the Bros. Landreth needed to shuffle their deck of live performers for the band’s summer tour. “We knew that we were going to be building a new live band from scratch,” says Landreth, who performs with his brother Joey. “Because we had a blank slate, we were able to dream up our ideal scenario, and we realized that it would be a trio with a singing drummer.”

Who else but Roman Clarke could fit?

“He’s a really talented drummer, but what makes him so great is that he’s much more than a gifted instrumentalist. He’s a brilliant artist in the broadest sense. He’s got a beautiful voice, he’s an accomplished producer, an amazing songwriter, and has a wicked sense of groove and dynamics,” Landreth says.

When he’s on stage, he remembers what it feels like to be in the crowd watching.

It’s a Saturday night in November, and there is hardly spare air to be breathed at the Good Will Social Club, where for the second consecutive night, Roman Clarke has sold every ticket the venue had to offer.

The opening act is Snackie, a local singer who blends R&B and pop and who happens to live down the street from Clarke. The room is loud, as it often is during the opening set, but Clarke stands at the back with a glass of water, tapping his fingers on the table and smiling quietly while his friend gets her moment in the spotlight.

Without a hint of annoyance, Clarke meets and greets fans, and politely shakes their hands. He smiles and waves at complete strangers. During a pause, I asked him if he was free for an interview in the coming days, expecting a phone call or 15 minutes in a coffee shop; instead, Clarke invited me to his house, where he recorded I Think It’s All a Dream during a marathon session last January.

ADAM KELLY Clarke performed at The Good Will in November 2022.

In the house during the recording were many of the people at the show, both on stage and in the crowd. It’s about them, Clarke says repeatedly: The Roman Clarke extended universe is too vast and interconnected to name names without leaving any out. He makes music to share, and he does so with everyone who shares with him.

“I think people love Roman because of his infectious ability to have a good time,” says Jen Doerksen, a friend of Clarke’s and a prolific Winnipeg music photographer and videographer. “He is committed to enjoying himself and having fun in life, and that’s something I can’t say of many people. That’s been one of the main ways he’s set me free from the burden of being myself. Spending time with him, I’ve learned to enjoy myself, be more expressive and less self-conscious, and overall, I just get to goof around and laugh and that makes me fall in love with him.”

The shows at the Good Will were booked months earlier, and with great anticipation, the city’s indie music community waited for the singing drummer to return to the stage. Clarke was just as excited. After a few years of a self-imposed silence, more committed to playing and producing for and with friends, with a few singles released here and there, the album release shows represented for Clarke a return to the front of the stage, where he sits comfortably in a black T-shirt.

“We’re going to play this whole album right now,” Clarke exclaims into the microphone. And he and his band do just that. Front to back. If you only listened to the melodies, which burst and bubble, you’d assume the album was about love found, not love lost. But I Think It’s All a Dream is a break-up album, with each track’s name written in capital letters. It’s a scream, but a pretty one that you can dance to.

The room is sweltering. There is actual steam. The coat check room is overflowing. Clarke’s shows at the Good Will always feel like this: it’s a party with an open invitation. “Who was here in 2017?” Clarke asks. “Who was here in 2019?”

“I think people love Roman because of his infectious ability to have a good time… He is committed to enjoying himself and having fun in life.”–Jen Doerksen, music photographer and videographer

Clarke had almost forgotten how loud this life was. How much fun it was to sit and do the only thing he’s ever done for money for an audience who pays him to do the same thing he’s done since he was a toddler at Filthy Lucre practice. But it got a little too loud for even his liking.

“I’m aware my shows are quite exciting, and that they’re essentially a big party,” he says a few days later. “But I got to literally the one point in the set where I wanted people to listen to me, so I asked them.”

He waits. He sits at the kit and asks with kindness for silence before playing his song, Church and State. After a few minutes, there is no noise.

It’s a song that feels different than all the others on the album. Like the rest, it is about depression and the emergence from it. It is about the inability to do basic things like getting dressed or make dinner as a long relationship dissipates into thin air. “You and I we’re like church and state. You and I we can’t stay away. You and I, we had good times, didn’t we? Don’t you wish it wasn’t over? Don’t you wish it wasn’t over?”

In that moment, Clarke opens the curtains to his heart. He shows that beneath the buoyant rhythms and joyful persona, behind the appearance of control, of success, of endless capability, of musical virtuosity, of love, there exists pain. The same pain and longing all humans know, have known, or will know at some point in time.

ADAM KELLY Clarke's performance at The Good Will in November was a sold-out show.

He finishes the song, and within a few minutes, a woman near the front faints, her asthma overwhelmed by the smoke machine and the heat.

Clarke snaps out of his moment. “We’re just going to pause for a quick second here,” he says. “Please be considerate of your neighbours,” he adds. “I hope she feels alright. Thank you for being a respectful and beautiful audience. It really is a pleasure to be up here.”

After the show ends, Clarke invites his bandmates and friends back to his house by the river, where the album was made. Where the puppy dogs occupy his bookshelf, where the pothos clippings propagate in a bottle once filled with Coca-Cola, where there is an upright piano and a Hammond organ and an acoustic guitar, and where on the walls are pictures his sister drew of dozens of the people Roman Clarke knows and loves.

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com

If you value coverage of Manitoba’s arts scene, help us do more.

Your contribution of $10, $25 or more will allow the Free Press to deepen our reporting on theatre, dance, music and galleries while also ensuring the broadest possible audience can access our arts journalism.

BECOME AN ARTS JOURNALISM SUPPORTER

Click here to learn more about the project.

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.