From Big Red to true Blue Bombers star quarterback’s leadership skills, spirit took shape under Friday night lights of eastern Ohio

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 10/11/2022 (1213 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Among Winnipeg Blue Bombers fans, it’s simply known as “The Throw.”

Trailing the Calgary Stampeders 28-19 midway through the fourth quarter of the final regular-season game of the 2019 CFL campaign, Zach Collaros took his place behind centre.

It was his first start as a Bomber, after being acquired in a last-minute deal with the Toronto Argonauts at the trade deadline just weeks before. It was a move made out of desperation, following injuries to quarterbacks Matt Nichols and Chris Streveler.

Facing second-and-seven from Calgary’s eight-yard line, the play started with Collaros taking a few steps forward in order to evade heavy pressure, before retreating. He rolled to his right, then curled left, only to turn back towards the right sideline.

By the time Collaros released the ball, in mid-run, he had travelled all the way back to Calgary’s 24. The perfectly thrown spiral sailed into the waiting arms of Darvin Adams in the back right corner of the end zone for a touchdown.

“I remember turning around and just watching Zach make a guy miss and run back towards our sideline. I thought he was throwing it out of bounds,” says Bombers offensive lineman Patrick Neufeld. “Darv then keeps his toes in and makes that catch, and everyone is like, ‘Holy cow.’ That was unbelievable. I’ve never seen a play like it before.”

The Bombers would go on to beat the Stampeders 29-28, with Collaros now cemented as the team’s new No. 1 quarterback. Winnipeg would win the next three games, all on the road, with Collaros leading the Bombers to the first of back-to-back Grey Cups and the franchise’s first league title in 29 years.

It was hardly the first time Collaros made a strong impression. That type of playmaking, determination and composure was forged years ago in the U.S. steel town of his childhood.

Today, Collaros is on the cusp of leading the Bombers to their third consecutive Grey Cup appearance. Next week, he is expected to be named the CFL’s most outstanding player (back-to-back years), and soon to be spoken of with the same reverence as the Bombers greats.

For Collaros, it’s been a long and winding journey to the top of the CFL.

To understand how far he has come, the Free Press travelled to where it all began: Steubenville, Ohio.

Steubenville, a city of fewer than 20,000, is located along the Ohio River, bordering the sliver of West Virginia that separates Ohio and Pennsylvania. It likes to consider itself a part of Pittsburgh, less than an hour’s drive east and the nearest big city, even if residents know the feeling isn’t reciprocal.

The most famous person to come out of Steubenville is Dean Martin, who, before becoming a world-renowned entertainer, worked at the local steel mill that long powered the city’s economy.

The mill closed in 1980, and was demolished nine years later. But the small city, in the heart of America’s Rust Belt, still likes to get its hands dirty, upholding its blue-collar character to this day.

There is no Uber or taxi service; in fact, the odds of hailing a cab are about as good as getting a bad slice of Steubenville-style pizza, which is to say rare. When giving out directions, much can be covered by saying either “at the top of the hill” or “across the river” or “over the bridge” or “near the stadium.”

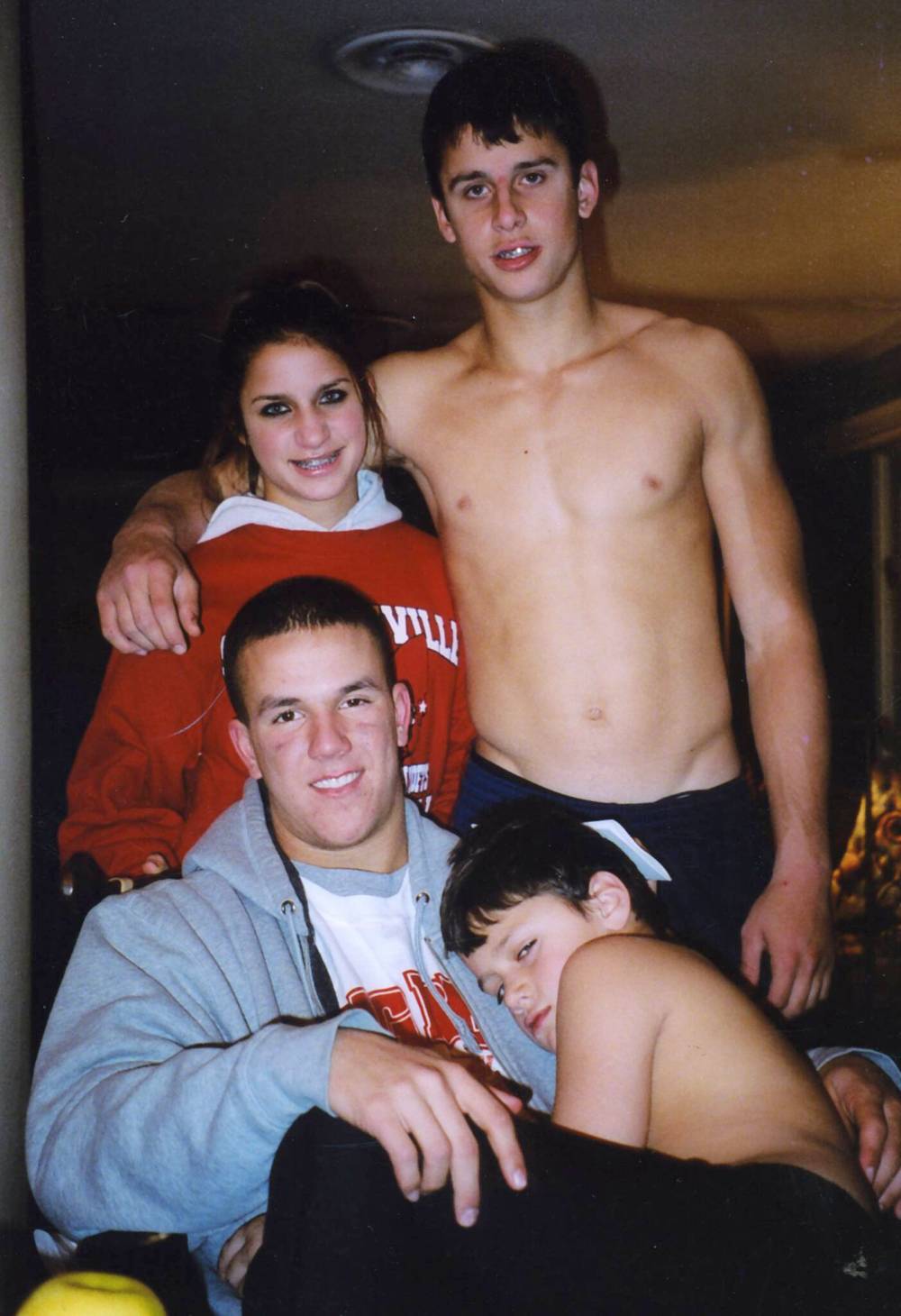

Collaros was born Aug. 27, 1988, to parents Dean and Michelle, who is affectionately known as Shelly. His sister, Lanae, is two years younger, and his brother, Dimitrios, came as a pleasant surprise seven years later, after Shelly was told she could no longer have children.

As the oldest child, Collaros adopted the role of protector, something the family says he comes by honestly from Dean, who is the director of finance at a local automobile dealership.

“He’s always cared,” Lanae says on a mid-October evening as she sits in the dining room of her parents’ bungalow in an upper-middle class part of town. “I thought all older brothers or just any brother, was like Zach. But then you realize later that they weren’t.

“But Zach was and still is the most competitive person I’ve ever met in my life.”

Lanae tells how the family used to head every Easter to her grandparents’ farm, where they would compete in an extensive scavenger hunt. This was no ordinary search; the hunt consisted of printed-off itineraries and individualized lists of what each sibling had to find, with the first to finish declared the winner.

Collaros concocted a plan to not only win but take away any chance for his sister to compete.

Instead of focusing on his own items, he would run around the yard looking to collect her stuff first, ensuring victory.

“They would try to chase Zach, who was eight, around and make sure he wasn’t playing defence and taking my items away,” Lanae says. “Board games, anything. It didn’t matter what it was. He wanted to win.”

That fierce competitiveness and deep desire to win, two characteristics that would come to define Collaros, come from his mother, who was an accomplished gymnast and track star. Like many kids in the area, Collaros’s childhood consisted of playing sports, where he would go on to excel in everything he did, notably basketball, baseball and, of course, football.

“I don’t think Zach had any other hobbies outside of sport,” Shelly says.

Dean doesn’t exhibit any ego as the father of a homegrown star. Instead, he is hesitant to gush about his oldest child. However, he doesn’t deny Collaros was special at a young age, capable of doing things beyond his years.

“My brother-in-law and I would throw a Nerf football to him when he was four years old,” says Dean, “and we’re throwing five, 10, 20 feet and at that age he’s running and laying out for it and catching it. It was like, holy s—.”

When Collaros played T-ball, he would retrieve every weakly hit ball before running — not throwing — out each batter. When Dean called out his son’s behaviour, Collaros would complain others weren’t able to catch the ball, to which his father countered they never would if they didn’t even get the chance.

When Dean started coaching basketball, Collaros would question every time he was taken out of the game, and later be reduced to tears in the car ride home. When he began playing baseball and a teammate botched what Collaros felt was a routine play, he’d slam his glove to the ground.

“I’d tell him to run over to the player, pat him on the ass and tell him he’s good. Be a leader,” Dean says. “For whatever reason, he was a bit above everybody else at those ages. I told him, ‘You need to be a leader, and if you make kids feel bad, they’re never going to want to play again.’ And he caught on to that.”

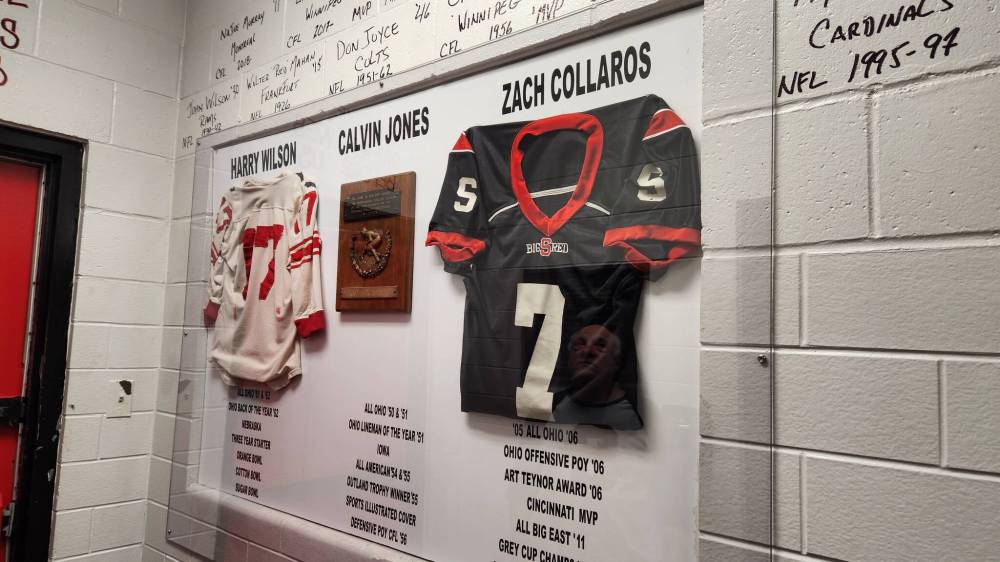

Take a stroll along the streets of Steubenville and it doesn’t take long to run into someone whose eyes open wide when describing the way Collaros used to dominate the local sports scene or brags about having a brother, cousin or uncle who was once his teammate. His No. 7 jersey and picture is plastered around town, with mini shrines to its favourite son in restaurants and bars, community clubs and personal care homes.

Collaros may be a star in Winnipeg, but it’s in Steubenville where he’s a legend.

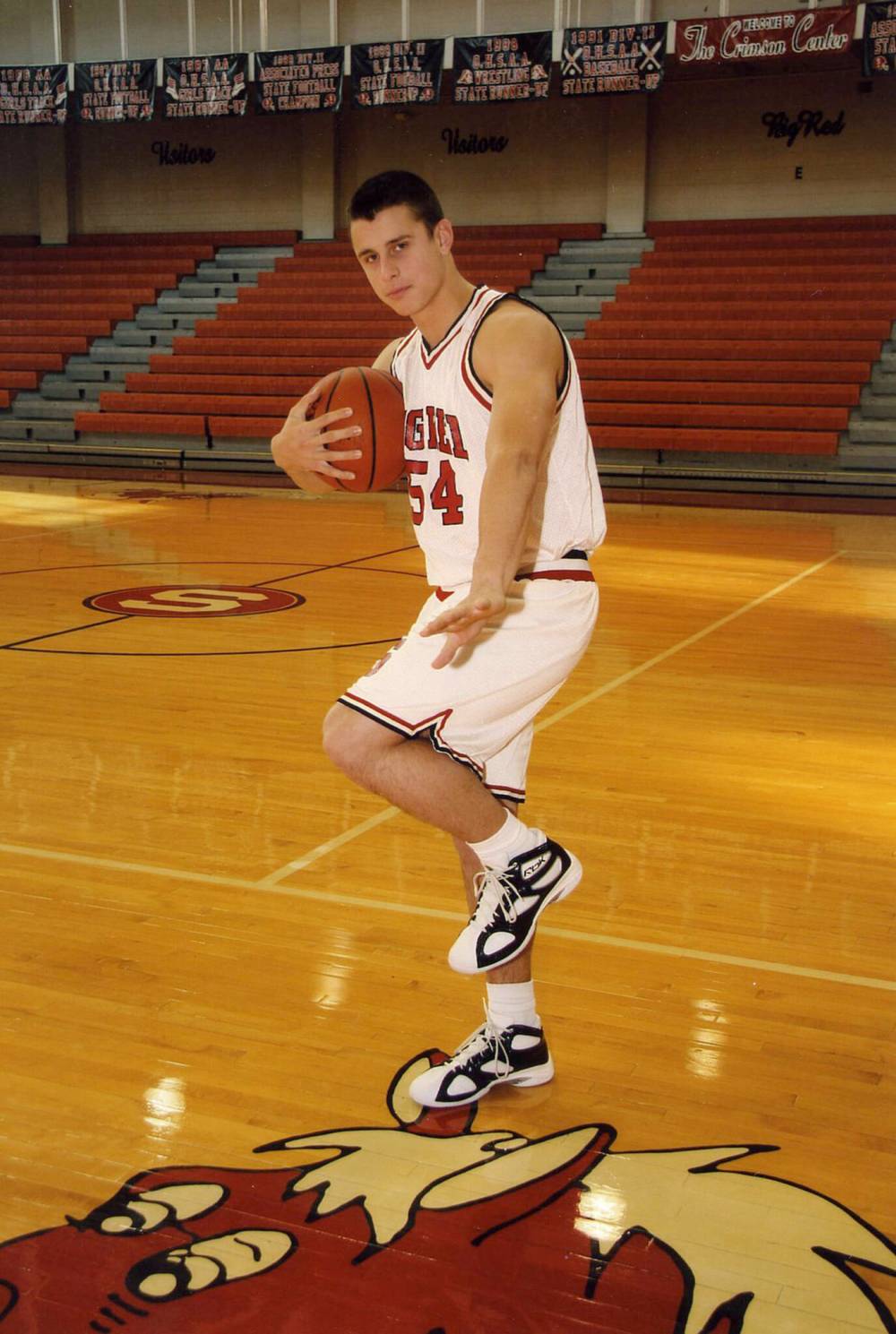

At Steubenville High School, Collaros was a force in basketball, averaging 19.8 points a game and being named to the All-OVAC (Ohio Valley Athletic Conference) first team. He was a talented baseball player, the first in head coach Fred Heatherington’s decades-long career to start as a freshman, playing all four years at shortstop, his success leading to scholarship offers from NCAA Division I programs such as Kent State and Marshall.

But it’s what Collaros accomplished on the football field that made him a household name.

Steubenville and Big Red football are synonymous. The city’s pride in the program, which began in 1897, and is touted as Ohio’s original dynasty, has been passed down through generations and culminates each week with Friday night high school football games at Harding Field.

Take in a game inside the 10,000-seat stadium in the heart of the city and you quickly feel the passion of a community that lives and dies with every win and loss. The noise of the marching band and cheerleaders offers the only respite from the constant stream of cheers and jeers from the crowd.

“It’s everything,” says former defensive co-ordinator Anthony Pierro, who is affectionately known as Coach P, when asked what Big Red football means to Steubenville. “When I got hired, the superintendent said to me, ‘I’m hiring you to win.’”

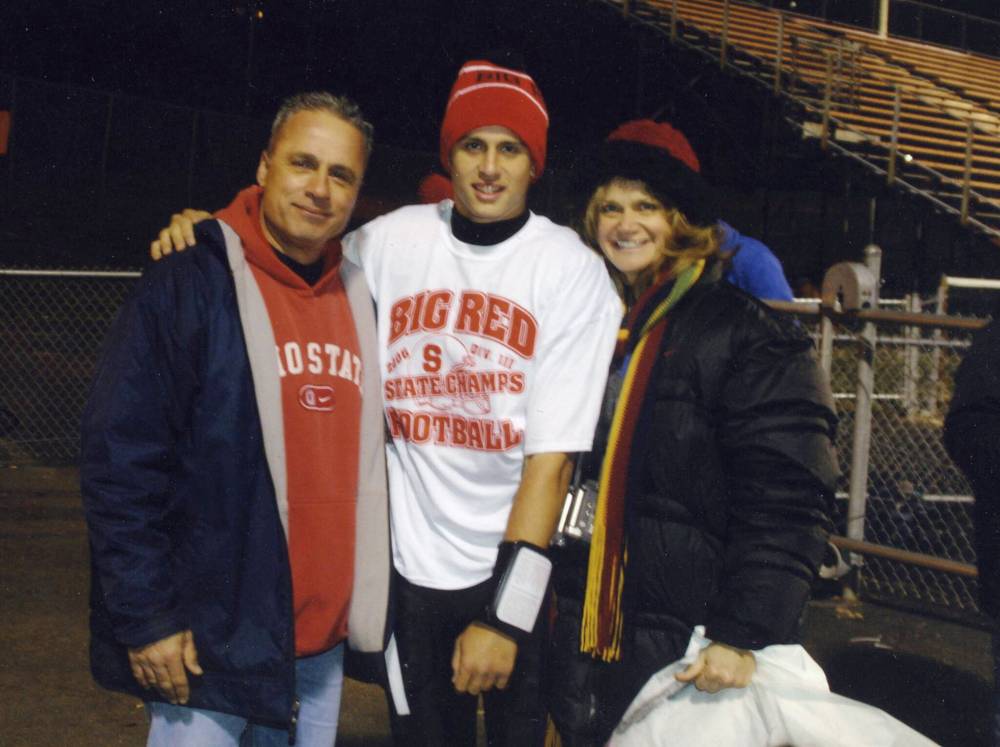

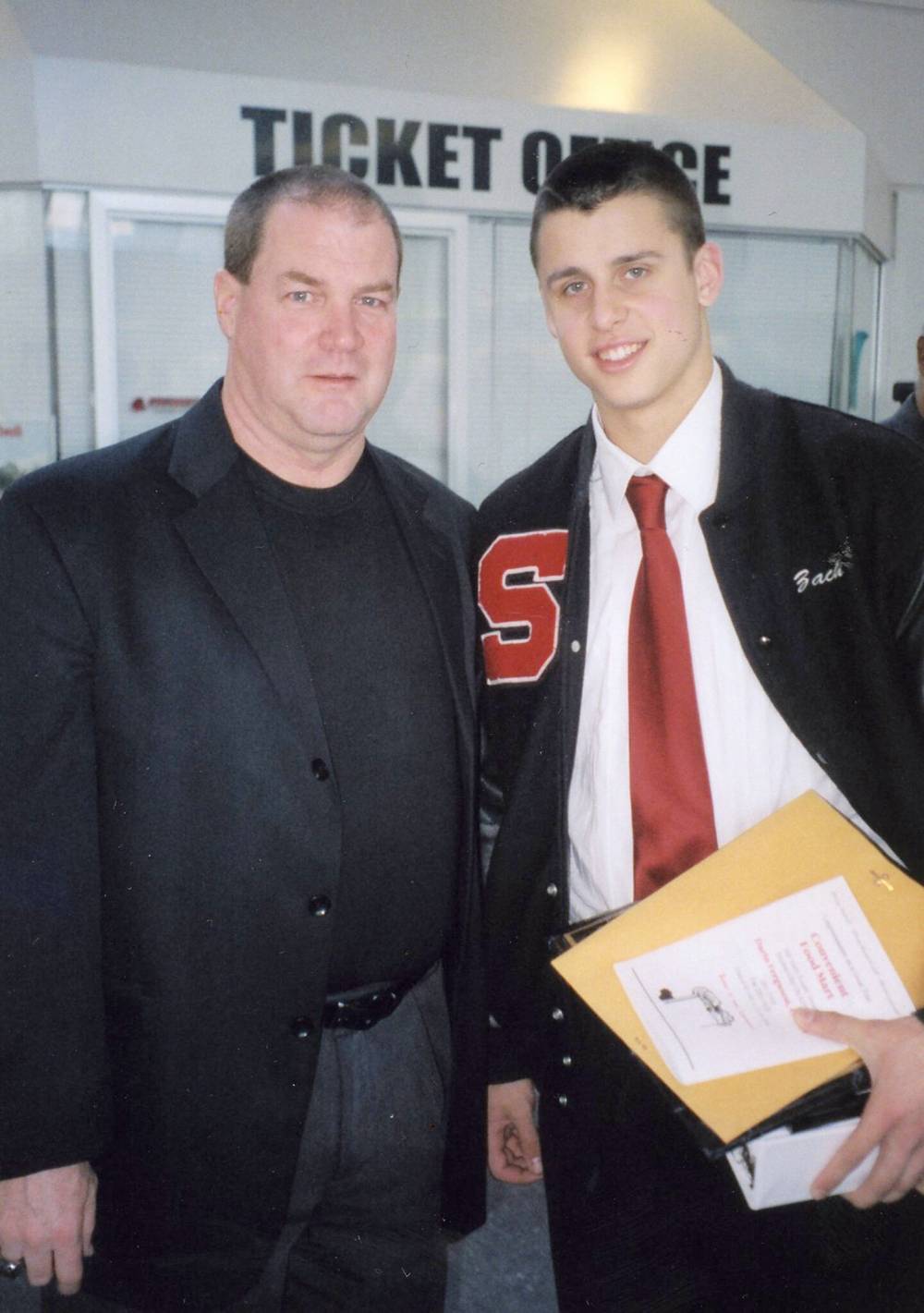

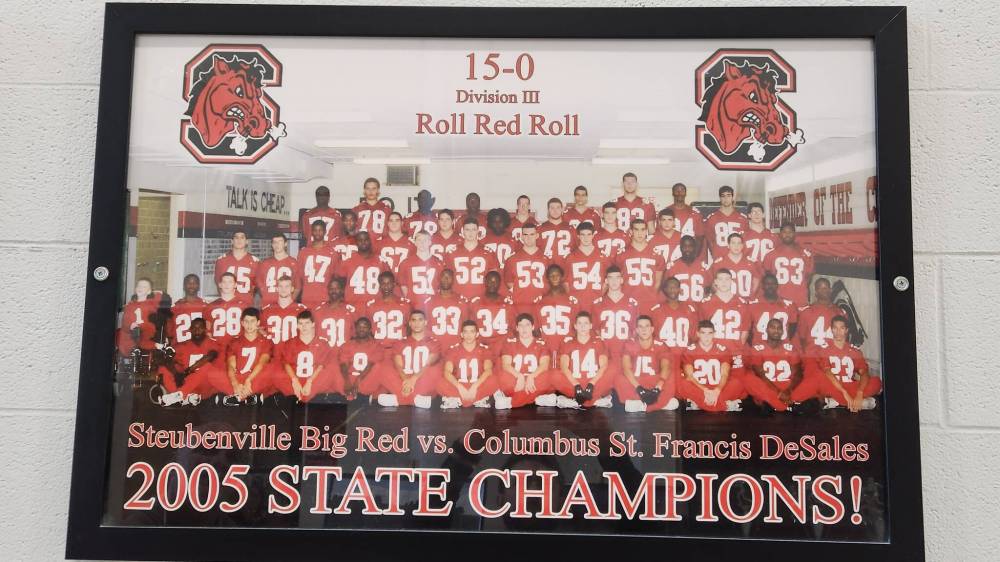

And win Collaros did. As a two-year starting quarterback, Collaros led the Big Red to a 30-0 record across the 2005 and 2006 seasons, capping each year with a state championship.

Collaros played on both sides of the ball, including at defensive back, with several of his coaches saying it was rare for him take a play off. But it was at quarterback where Collaros excelled — he holds the school’s single-season records for passing yards (2,513) and touchdown passes (30).

“He’s a hard worker, but he’s also someone who never took anything for granted, even though he was the most athletic,” says Mike Haney, Collaros’s former quarterback coach with the Big Red. “We had a good team, but he was the leader and they saw the way he worked and everyone wanted to follow him.”

Even before joining the varsity team, Collaros dominated, going unbeaten through Grades 7 and 8 at Harding Middle School, and losing just once in Grade 9 — which, locals will be quick to remind you, came against a junior varsity team and not a fellow freshman club.

Even with all that success, those closest to Collaros say he never wavered from his humble approach to the game. While it was easy to marvel at his athleticism and smarts on the field, there was an equal appreciation for how he carried himself away from it.

“Zach always had the bigger picture in mind,” says Sam Busic, a former Big Red teammate and close childhood friend who grew up on the same street as Collaros. “There was a group of us that lived close by and whenever we were done playing basketball or football and the rest of us would go out, Zach would honestly go home and probably do push-ups or sit-ups. He was a leader right from the start.”

Bryan Mills, principal of Harding Middle School, coached Collaros in his Grades 7 and 8 football seasons. It was evident Collaros had a level of maturity rare for such a young age, he says.

The football team ran through Collaros, who, as the quarterback, made sure everyone got a chance to touch the ball, Mills says. But his desire to have everyone involved went beyond the gridiron.

“I get chills just thinking about it. Here at the school, we have no mandatory seating and about 400 seats in the cafeteria,” Mills says.

“Zach would often go sit with the kid that had no one to sit with, and then all of his friends would follow, too. Even though he was popular, handsome and was the star athlete, he never celebrated that and always wanted others around him to feel good.”

Many say Collaros’s humility comes from how he was raised by his family. Collaros watched as both his mom and dad put in long workdays, making sacrifices for their children to pursue opportunities in and outside of sports, a privilege he’s acutely aware wasn’t afforded to everyone.

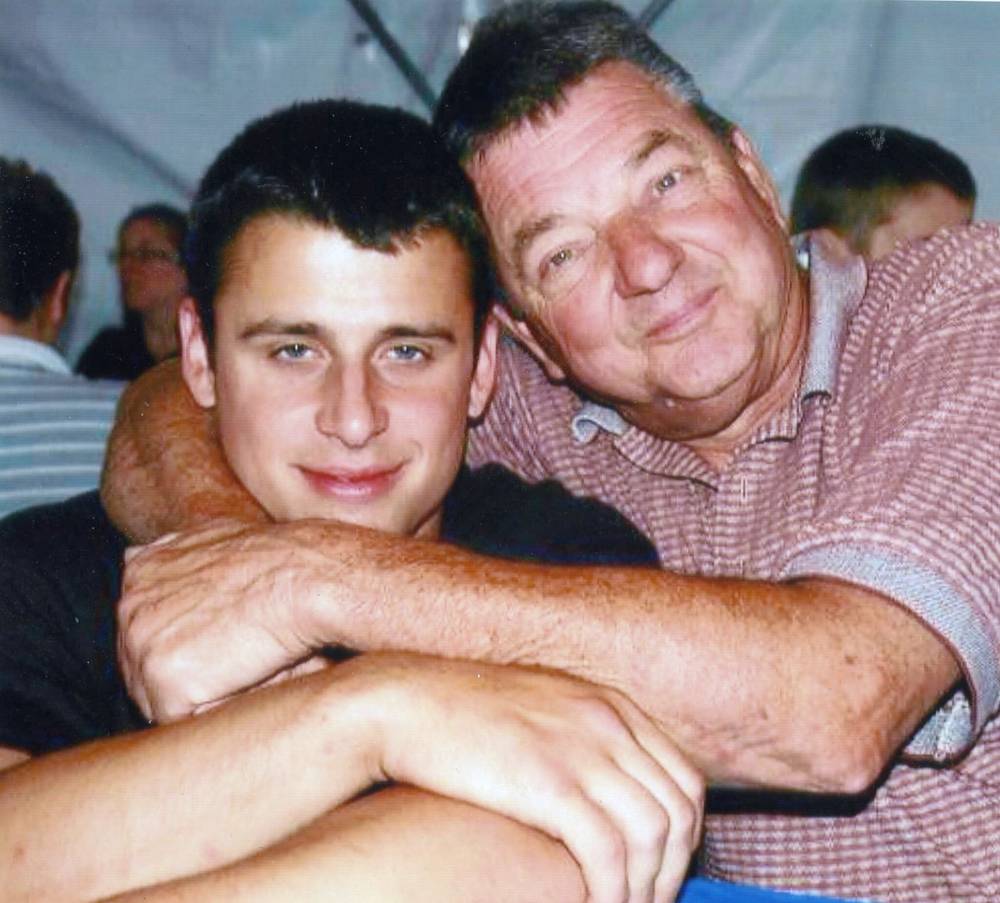

There was no greater fan than his grandfather. Known as Pap Pap, Jim Glaser would attend every one of his grandson’s games, even when he played in the CFL, until his health ultimately declined. He died in 2018.

Shelly says her son, beginning as a young child, always hated disappointing people, which was likely the result of all the support and encouragement he received from the greater community.

“This town has a lot of respect and love and loyalty for him,” she says. “They just want him to do well, so I think that makes him feel a special way about where he’s from.”

In an effort to give back to the people who gave him so much, Collaros, along with Mills, Busic and hometown friends Mike DiCarlantonio and Jeff Bruzzese, started the Zach Collaros Foundation in 2016. Together, they’ve raised thousands of dollars through annual golf tournaments and special events, all of which is filtered back into the community.

The money is used in various ways to support children, including purchasing necessities such as deodorant and notebooks, as well as extra lunches to be sent home over the weekend or on holidays, and for scholarships that are less about sports and more about enhancing a student’s learning experience.

The foundation is meant to level the playing field for children who aren’t as lucky to live the kind life Collaros had growing up.

While Collaros dismisses any credit for what he believes is a responsibility to give back, his friends don’t mind singling him out.

DiCarlantonio provides a window into what it was like to call Collaros a close friend.

When DiCarlantonio had serious health issues in Grade 8 that required surgery in Pittsburgh, Collaros spent the entire night calling him and making sure he was OK. When DiCarlantonio’s grandma passed away years later, Collaros was sure to attend the funeral.

It wasn’t always grand gestures. It could be as simple as how Collaros interacted with people, always wanting to know more about the person he was speaking to, rather than focusing on himself.

“Just that genuine care, that genuine love, he’s always the first one there,” DiCarlantonio says in a phone interview from his home in Columbus, Ohio, as words catch in his throat, requiring him to take moment to gather himself. “It shows he’s family, right? Yeah, he’s like a brother.”

No one who grew up with Collaros is surprised by his CFL success. Most will tell you they always envisioned great things for him.

Fred Heatherington, Collaros’s high school baseball coach, is convinced he would be playing professionally, possibly in the major leagues, had he stuck with baseball.

Collaros started to attract some major attention from baseball scouts by his senior year, catching the eye of one in particular, Scott Stricklin, who was recruiting for Kent State at the time, but is now head coach of the University of Georgia Bulldogs. When Stricklin saw him excel at a local tournament, he tried to get a formal commitment.

Without consulting his family, Collaros initially agreed. That didn’t sit well with his parents, who weren’t thrilled with not being involved in such a big decision, not to mention Kent State, which was also offering a spot on the football team, was only willing to cover half his schooling.

Meanwhile, there were intense efforts to get Collaros into an NCAA Division I football college. Haney, Collaros’s high school quarterback coach, mailed DVDs featuring Collaros highlights to about 100 colleges.

“I just wanted to make sure people knew what he was doing and how special he was,” Haney says.

Pierro, Big Red’s defensive co-ordinator, was also working the phones, including a call to longtime mentor Pat Narduzzi. Narduzzi, now at the University of Pittsburgh, had just taken the head coaching job at Michigan State.

“I was begging him to give Zach a shot while he was at Michigan State, and he was this f—ing close,” Pierro says, sitting on a bar stool in the basement of Dean and Shelly’s home.

“We’re actually on the phone, and I say, ‘Coach Narduzzi, I’m telling you this kid’s a player. I would not just say this, he’s a f—ing player.’ And right when we’re talking, he goes, ‘Coach P, Kirk Cousins (current quarterback of the NFL’s Minnesota Vikings) just walked through the door — we don’t need a quarterback.’”

Collaros would eventually catch the eye of Brian Kelly, then-incoming head coach at the University of Cincinnati. With a full scholarship, Collaros initially played football and baseball his first two years as a Bearcat, before committing to football exclusively for his final two seasons.

In 2010, his third season and first as the team’s starting quarterback, Collaros led the Big East with 2,902 passing yards and 26 touchdowns, and was selected as the first-team All-Big East QB.

At around 5-10 and less than 200 pounds coming out of high school, several college football scouts thought Collaros was too undersized to be effective.

It was the same story when it came to his NFL draft year in 2012, with all 32 teams electing to take a pass. Collaros would end up signing with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, but lasted barely a weekend before they cut him loose.

It was the first time he had been cut from any team and Collaros considered calling it quits.

“I wasn’t rattled, like… it broke me down for a bit, for like a week,” he says. “It was more, wow, I’ve never had that feeling before. So, that was weird.”

When the CFL came calling, he hesitated before deciding to give it a shot.

“He was upset. He wanted to be in the NFL,” Shelly says. “But with Zach, his mindset has always been whatever position he’s put in, he’s going to make the best of it and he’s going to do the best that he can.”

Collaros’s 11-year run in the CFL has been an equal blend of incredible highs and crushing lows.

While it’s easy to pinpoint the positives — three Grey Cup-winning seasons, being named the CFL’s most outstanding player, two league all-star nods, among other accolades — it’s also impossible to ignore the challenges.

Most of Collaros’s struggles in pro football have centred around injuries, each one seemingly worse than the last.

In 2015, in the midst of a breakout season with the Hamilton Tiger-Cats, Collaros tore the anterior cruciate ligament in his right knee, sidelining him the rest of the year. He would return midway through the 2016 campaign, which ended with four consecutive losses, and followed that up with an 0-8 start to the 2017 season.

Collaros was posting the worst numbers of his career, and would eventually be replaced by backup Jeremiah Masoli in running the offence.

That set the stage for a couple of seasons with the Saskatchewan Roughriders.

It was in Saskatchewan where Collaros would suffer a string of concussions that put his career in doubt. He missed four games that first year, and though he led the Roughriders to a 12-6 record, was ruled out of the west final against Winnipeg after sustaining another concussion.

Collaros opened the 2019 season feeling healthy and was once again named the starter in Saskatchewan. He’d last three plays, before suffering a third concussion on a dirty hit from former Ticats teammate Simoni Lawrence. Months later, after a brief stint with the Argos, he was traded to the Bombers.

Watching him take violent hits led many to question whether Collaros should continue playing.

“Having to go through all the ups and downs that he did, it wasn’t easy for people back home who care about him,” says Andrew Radakovich, a close friend and former Big Red teammate who was in the crowd to witness the hit from Lawrence. “He’s a superstar, athletic-wise, but everyone really likes him as a person. You want him to be successful, but most of all you want him to be healthy.”

To understand why Collaros never gives up, you must return to Steubenville. It’s here where he was conditioned to be Big Red tough.

It’s a process every player goes through to show accountability to their teammates and prove they’re strong enough, both physically and mentally, to don a Big Red jersey. And it starts in the gym beginning as early as Grade 6.

Students who want to one day play Big Red football first join what is called lift club, where at least once a week they’re taught how to properly lift weights.

“By the time you get to high school, you have baby fat on you still, but when freshman or sophomore year starts, when you start puberty and getting into it, that’s when you start learning how to really lift,” says Steve Davis, a former Big Red teammate of Collaros and current brother-in-law. “It was about starting to build muscle early, building a foundation for when the real work began.”

The “real work” starts later in high school, and would require even more discipline and, ultimately, pain. Davis chuckles a bit as his wife Lanae encourages him to explain what it means to do “death row.”

“Let’s just say, that’s where you’re really held accountable,” he says.

It was a weekly exercise routine where players went through a circuit of 25-30 different stations — everything from bench press to sled drills. The point was to go as hard as you could at each station until you couldn’t give any more.

Not everyone would make it. Some would throw up, others would defecate themselves and others, in some cases, were carried out of the gym.

While gruelling at the time — and it’s no longer practised at the high school — Davis looks back on it as a positive experience that’s helped him get through life’s most challenging moments.

“The reason why we go through death row, yes, it’s going to build muscle, but more so it’s going to build character and in that fourth quarter, if we’re down by six points with two minutes left and we have the ball, you’re not going to shut down. You’re going to be able to get through it because you’ve been through tougher times,” Davis says.

“The whole thing, from sixth grade on, it’s like a commitment. You can get out, but no one wants to. People do feel like you’re disappointing people. And nobody stood for Big Red tough more than Zach.”

Now 34, Collaros has seen it all — from near career-ending injuries to an inspiring comeback.

And that ability to see? Well, that was there right from the beginning.

“I always felt when I was a kid, and I never said this to anyone before, but things kind of just moved slower for me,” Collaros says over a pizza supper at his Winnipeg home. “When I was playing basketball, I could dribble to get to a point where I would know that in one second a teammate would be there and I could throw a bounce pass. It was the same thing with baseball, I just knew for some reason where the ball would go off the bat. And in football, especially as a defensive back, I just knew where the ball was going to go.”

His high school coach agrees.

“He’s not fast. He’s not quick. He’s not elusive. But he feels,” head coach Reno Saccoccia, who has led the Big Red the last four decades, says while sitting in his office at Steubenville High School. “He can feel what’s going on around him without seeing it. Some quarterbacks have knowledge. Some quarterbacks have feel. He has both.”

His high school lessons have never left him. It’s where he first learned how to dissect film and properly prepare for an opponent. In fact, he would spend hours in defensive co-ordinator Pierro’s classroom going through tape.

“Zach would be right next to me most of the time,” Coach P said last month over dinner at the Collaros household.

It was an extracurricular the Collaros family didn’t fully support at the time.

“Quite frankly, we were kind of pissed off about that once we found out what was going on,” Dean says. “‘Are you taking any classes, Zach, or were you in Coach P’s room eight hours a day?’”

Then, there was the work Collaros put in with Big Red offensive co-ordinator, Bob Radakovich, who often stressed the mental side of the game. Radakovich would get Collaros to read academic papers on psychology, and it was through that research he discovered the benefits of visualization.

Together they would go through an entire game plan with their eyes closed. To illustrate, Collaros gets up off his chair and grabs a nearby play sheet and starts calling out different plays, his eyes now shut, while going through various throwing reads.

It’s something he still does to this day, and has passed on to his fellow quarterbacks with the Bombers.

“It makes me accountable to my teammates, so they know I’m putting in the work and I’m not leaving any stone unturned,” Collaros says. “Like in anything in life, you always have to be prepared for your opportunity.”

Nicole Collaros is in the kitchen of their south Winnipeg home, wrapping up final preparations for dinner.

Two-year-old Sierra and her sister Capri, just days away from her first birthday, are playing quietly in the living room. The TV is on, but neither is interested. Sierra is focused on Capri crawling across the carpet on all fours.

It’s the calm before an inevitable storm. Soon, all hell will break loose.

There’s a knock at the door. As it opens, both girls make a beeline for the front entrance.

“Daddy! Daddy!” yells Sierra, as she runs into Collaros’s arms.

Capri is crawling feverishly to catch up, but her timing is nonetheless perfect, as dad plants a big kiss on her cheek before carrying her to the kitchen.

This is life away from the gridiron.

It can be as chaotic as dodging would-be tacklers on the football field, but it’s a sack this quarterback would take any day of the week.

On the field, Collaros led the CFL in passing touchdowns in the 2022 regular season, with 37, and his 4,183 passing yards were good for second among quarterbacks, while guiding the Bombers to top spot in the West Division with a record of 15-3.

Since joining the team, Collaros is 32-4 as the club’s starting quarterback, his sensational run on the Manitoba prairie all but guaranteeing a future place in the Canadian Football League Hall of Fame.

But it’s at home, where the love Collaros has for Nicole and their daughters is clearly evident, is where he’s doing everything he can to rack up more wins.

Family has always been the most important thing in his life, and to be able to build his own has been a highlight more meaningful than anything he’s done in sports.

“Just the way I was taught growing up — from a work ethic standpoint, from an accountability standpoint, from a teamwork standpoint — all those lessons, and there’s a million of them, I’ve carried with me through life and they’ve moulded me as a person,” Collaros says over dinner.

“I want to be the best dad I can be, I want to be the best husband I can be, I want to be the best at my job as I can be, and it all stems from not wanting to let those people down who invested so much in me and did it for nothing in return, just out of the love for me or love for the community.”

Collaros says Sierra is most like him — she might seem like she has a hard shell at first, but she’s the sweetest little girl once she warms up to you. Capri takes after her mother, the eternal optimist with a smile that lights up the room.

Nicole chuckles a bit when sharing how she met her husband, which didn’t exactly go as planned. Collaros was early into his time with the Tiger-Cats and Nicole was being pressed by a friend to go on a date.

They planned to get together after a Ticats game in Toronto, as Nicole is from the GTA and wasn’t all that keen on making the trek to Hamilton. But when it came time to meet, Collaros was a no-show.

Nicole still likes to remind him about how cute she looked that night, while Collaros claims it was an honest mistake.

He adds he was reeling from a loss to the Argos and that it had slipped his mind.

“(Our offensive co-ordinator) Tommy Condell late in the game called a screen pass on second-and-six — a screen! — and it was like, let me just figure it out,” Collaros recalls, as if he’s right back there.

It was nearly a year later before they would finally go on that first date. It only took a few minutes more for Collaros to fall in love.

“She helps me see the positive in every situation and just settles me down,” says Collaros. “She really changed me. Not that I was someone incapable of feeling that love, it was just instant with her. She challenges me in ways I need, and it just makes me never want to hurt or disappoint her.”

It took less than a month for Collaros to bring Nicole to Steubenville to meet his family. The way he adored his niece Lucy, now 11, was further proof for Nicole that Collaros would make a great father one day.

“He seems really serious on TV, but once you get to know him, he’s really funny, really sweet and actually pretty sensitive,” Lucy says. “Living so far away, it’s probably really hard for him. Whenever he comes home, he just has the best time, makes every moment count.”

When they got married — and it was a big wedding — everyone from Ohio who was invited, attended.

It was a testament to how much Collaros was loved, but also to who he is and the relationships he’s formed everywhere he’s gone.

“He’s generally just a private guy who doesn’t like the spotlight and I think that’s what draws people to him, because he’s just a humble and simple guy,” Nicole says. “Then you visit Steubenville and you see where he comes from and all these things make total sense.”

Nicole is more like her husband than she thinks. She has stuck by Collaros through all his CFL stops — from Hamilton to Regina to Toronto to Winnipeg — a journey that has meant making several sacrifices, including putting her teaching career on hold and leaving the house they built in Ontario for half the year, but she’s not interested in being singled out.

Such is life for a football family, as professional sports can be anything but stable. It’s for that reason they’re both grateful to be in Winnipeg, where Collaros’s stock only appears to be rising, fresh off signing an extension that will keep him here through the 2025 season.

Shortly after signing his new three-year, $1.8-million contract last month, making him the league’s highest-paid player, Collaros noted the blessing he got from Nicole and how important it was to him to make sure it was the right decision for their family.

“We make all decisions together,” she says. “It was very easy, even for the past few years, a no-brainer to stay in Winnipeg because of how happy he is here.

“I’ve seen him in so many different scenarios where his stress was constant and you could tell it was affecting his desire to play. You have to be in the right situation, and here it’s special, the entire organization is special, and it feels like home.”

Collaros is cut from the same cloth as head coach Mike O’Shea and there isn’t a teammate with whom he wouldn’t put in extra hours watching film or grab a beer. With several players also having young children, Nicole feels lucky to create meaningful friendships with other families, all of which have been nothing but gracious since they arrived late into the 2019 season.

Neither of them knows what the future holds, even if there is some added security with a long-term deal now complete. Nicole teases the possibility of adding to their family, while Collaros jokes about having to play until he’s 50 to afford living near Toronto.

Whatever does come their way, Collaros will be ready for it. Always prepared, always grateful, always wanting to make those closest to him proud.

jeff.hamilton@freepress.mb.ca

Jeff Hamilton

Multimedia producer

Jeff Hamilton is a sports and investigative reporter. Jeff joined the Free Press newsroom in April 2015, and has been covering the local sports scene since graduating from Carleton University’s journalism program in 2012. Read more about Jeff.

Every piece of reporting Jeff produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, November 11, 2022 11:15 AM CST: Corrects typo