Damning disinterest

A large majority of Winnipeggers chose not to buy in to what civic race was offering

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/10/2022 (1136 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The numbers will haunt Winnipeg for the next four years, in one way or another. There are a few that stand out. They tell us a little about Winnipeg, and a lot about this election. And they’re a warning sign about our civic politics, if not quite — or not yet — a 911 call. So let’s take a moment, and review some of the key figures.

Here’s where we start: 27.5 per cent. That’s the share of cast ballots that lifted Scott Gillingham to the mayor’s chair, and it’s both the smallest vote total and the smallest share for a winner in this city in over 50 years. It was enough, in this case, for a razor-thin win over Glen Murray, whose early lead collapsed by his own hand, but it shouldn’t be confused for a triumph.

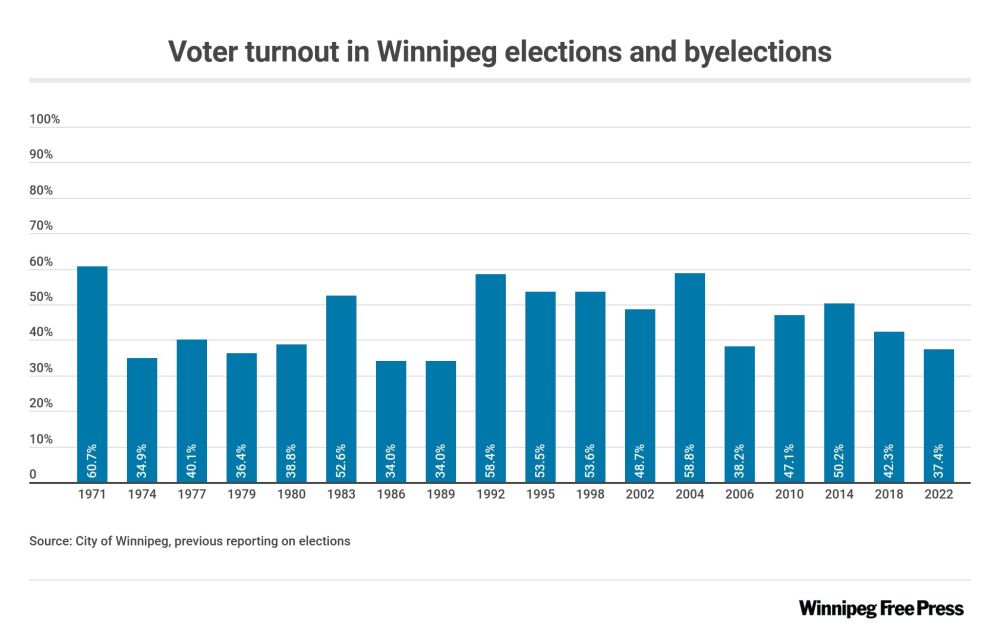

Because here are some other numbers that stand out. In the days leading up to Oct. 26, advance turnout at some locations was high, leading election officials to predict “very large turnouts.” But in the end, of Winnipeg’s 521,191 eligible voters, the majority stayed home: only 37.4 per cent of us cast a ballot. Over six in 10 did not.

Which leads us to another figure of note. Of the people who did vote, a smidge over half chose either Gillingham or Murray. But 47.2 per cent cast their ballot for one of the nine other people running; in a race that did have two clearly-defined front-runners, the spread could be interpreted as a rebuke of the options on the table.

Or, to put it another way: Winnipeggers knew one of the two at the top was likely to win. They knew, by late October, that it could be very close. Perhaps such a race might draw even frustrated voters to hold their nose and pick the leader they found least objectionable; Canadians are no strangers to strategic voting, after all.

Yet in the end, even knowing that either Murray or Gillingham was likely to win, nearly half of voters decided they could not, in good conscience, play their own small part in the battle between those front-runners. So they looked elsewhere, and found in the wide field a smattering of options that suited them. And there’s something interesting, in how that played out.

In mid-September, over a month before the election, Probe Research took a poll of Winnipeg voters, gauging their electoral intentions. At the time, Murray was handily leading over Gillingham, by a difference of 40 to just 15 per cent. But below the two front-runners, there’s something interesting about how those September poll numbers compared to the final result.

Other than Murray and Gillingham, most of the other nine candidates earned vote shares very close to what the September polling had shown. Klein, who entered the race late, had a small boost; but the next four candidates in Shaun Loney, Jenny Motkaluk, Robert-Falcon Ouellette and Rana Bokhari finished exactly where they’d been predicted.

This suggests to me that, by mid-September, many decided Winnipeg voters already knew that no matter what happened at the top of the race, they wanted no part of it. So when Murray’s support collapsed amidst reports of toxic bullying of staff at his previous job, many of his voters likely went to Gillingham; but relatively few others were moved to weigh in.

To be fair, that might be true in most races. But in a campaign where nearly half of Winnipeggers who did vote didn’t want to vote for either candidate with the best chance of winning, even as their battle grew tighter and the choice of which one was fit to lead grew more urgent, that seems to symbolize something greater than just a large field.

And that takes us back to that other, most damning figure: the 62.6 per cent of eligible voters who didn’t vote.

Of all the topics in democratic governance, few provoke more frustration than the question of why people don’t vote. To put it bluntly, it infuriates people when others don’t vote: in the wake of Wednesday’s results showing a flaccid turnout, we saw plenty of that anger: “F— voter apathy” was one of the first tweets I saw after flicking onto my phone.

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS A voter heads into the polling station at the Youth for Christ building on King Street Wednesday to take part in Winnipeg’s civic election. Only 37.4 per cent of the city’s eligible voters cast a ballot.

This isn’t new. Voter turnout is a constant source of hand-wringing across the U.S. and Canada, though the reasons for low turnout vary by jurisdiction. In a number of U.S. states, for instance, turnout is deliberately suppressed by moves to raise barriers to voting as part of a demographic power game; elsewhere, the issues deflating turnout are more banal.

So finding a solution to boost turnout depends on an accurate diagnosis of the problem. Where barriers are high, they must be reduced. Structural changes can help: in Australia, where voting is compulsory, rates hover around 90 per cent. The state of Oregon has long enjoyed high voter turnout, in large part due to its convenient vote-by-mail system.

But in Canada, where barriers to voting are relatively low compared to some peer jurisdictions, I cannot help but see the low turnouts as a symptom of disappointment. We are, for the most part, a very disappointed electorate, and have been for very long. Maybe we should drag ourselves to the polls to pick someone anyway, but is it so wrong if most of us did not?

Call this my defence of not-voting. It comes down to this: if we believe in democracy, then there has to be at least a little bit of idealism still in it.

Call this my defence of not-voting. It comes down to this: if we believe in democracy, then there has to be at least a little bit of idealism still in it. We shouldn’t succumb to the tendency to see participation through a cynical lens of defining voting as something one must do, no matter how little the options reflect our hopes or needs, no matter how disappointing.

If one cannot in good conscience put their mark next to any name on the ballot; if one looks at a campaign and doesn’t see a candidate or party who is likely to improve one’s material conditions, then why should they participate? If the message is “F— voter apathy,” then that anger should be directed to a political culture and system that makes people apathetic.

The hitch in that idealism, of course, is that it doesn’t matter to the winners how many people stayed home. At least, not in the short term. Yet those elected, who got in on such low turnout, should bear in mind that somewhere out there are a whole lot of people who weren’t convinced; and those voters will still be there, waiting for someone to inspire them.

I don’t write that as a critique of Gillingham, or of anyone. Only a reminder that Gillingham is now mayor for all Winnipeg. Not only the 27.5 per cent of active voters who chose him, or the fewer than one in 10 eligible voters who did. So as he goes forward, may he remember that a majority looked at what the whole race was selling, and decided not to buy at all.

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, October 31, 2022 1:23 PM CDT: Updates voter turnout chart, which previously reported an incorrect figure for 1980.