Manitoba’s greatest architect dies at 92

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for four weeks then billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 14/10/2022 (802 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

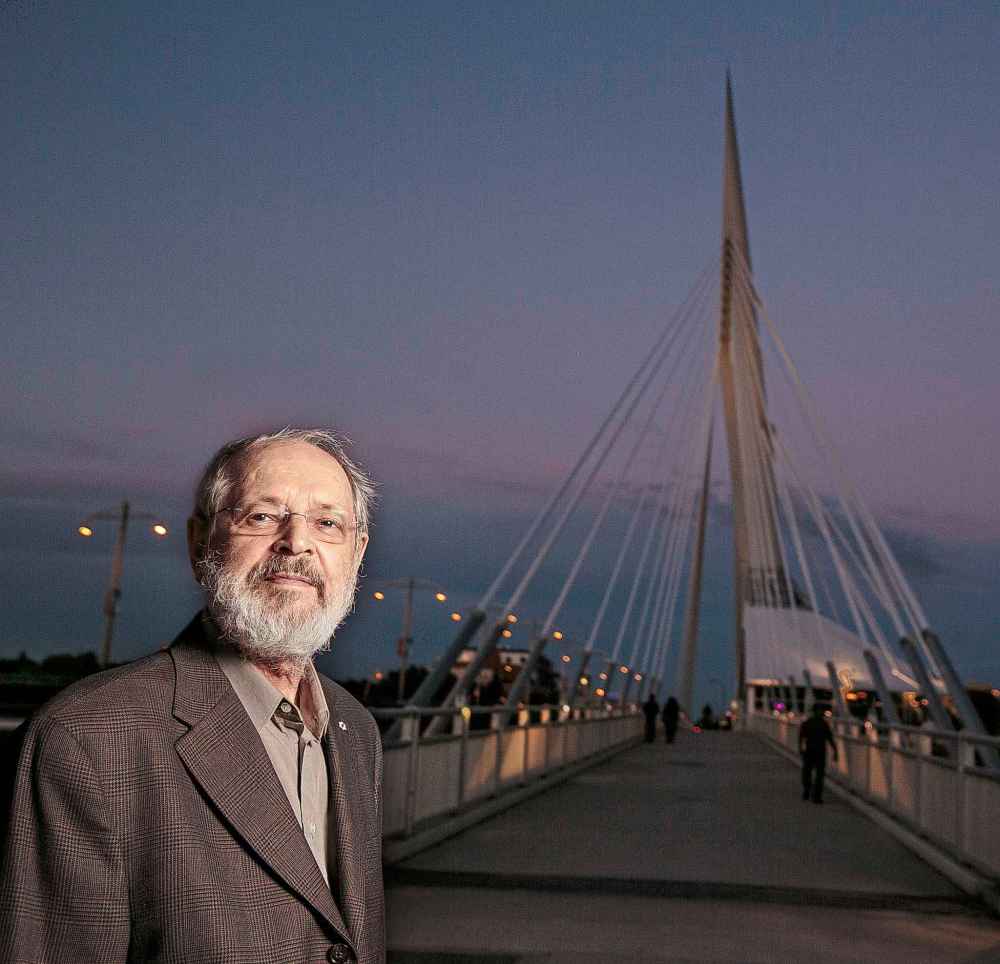

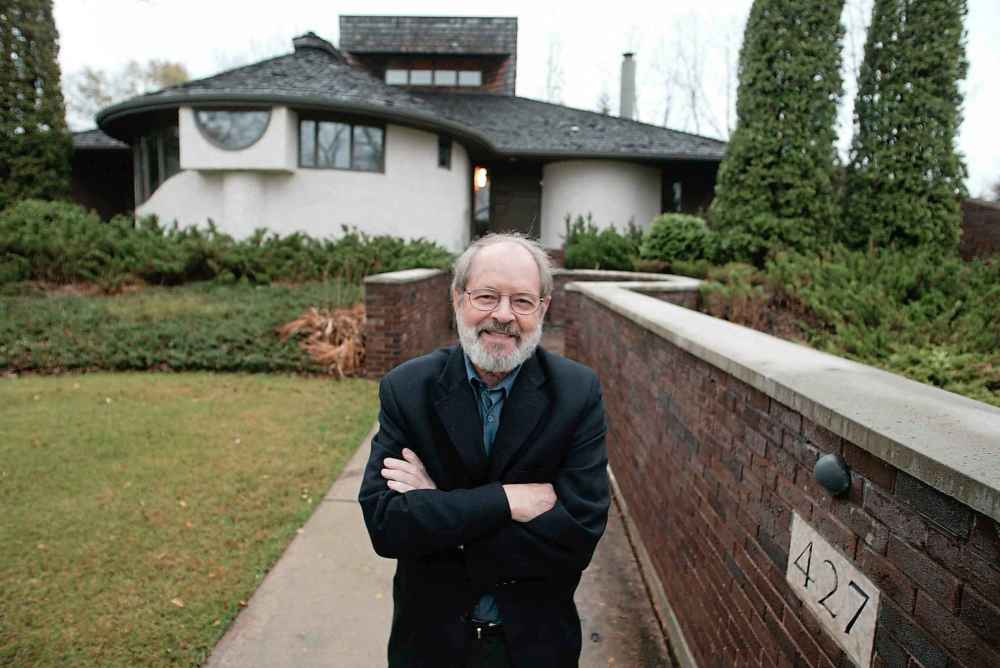

Étienne Gaboury, a titan of his craft largely considered Manitoba’s greatest architect, has died at 92.

Gaboury, who was born in a large family on a farm near Bruxelles, Manitoba in 1930, spent over 60 years sculpting the province’s identity through his building designs and artwork.

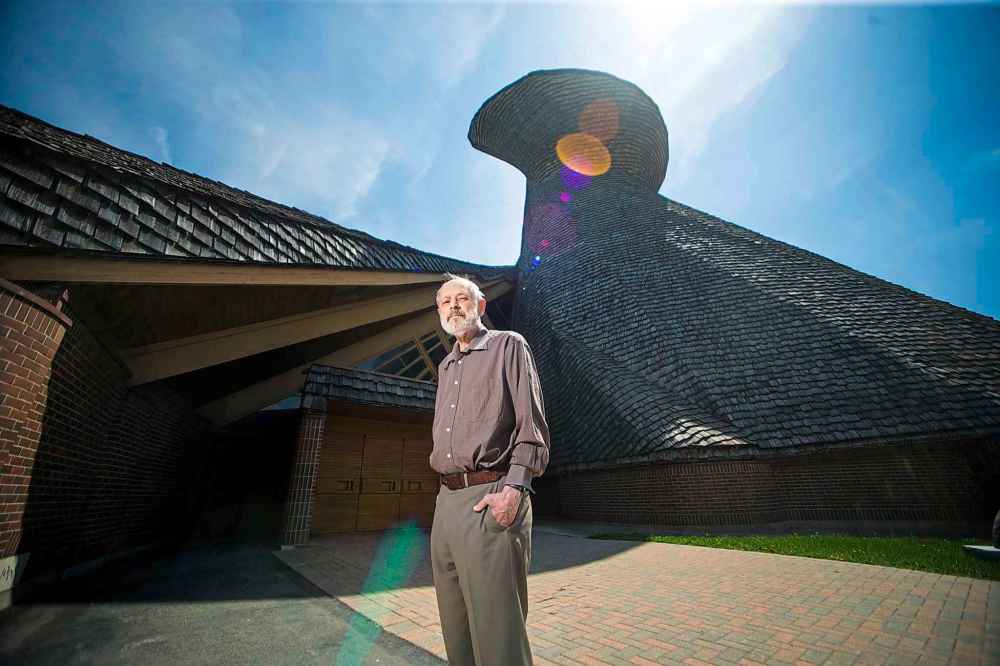

Among his works are the Church of the Holy Martyrs, l’Église de Précieux Sang, the Esplanade Riel, the Canadian Embassy in Mexico City, the Centre culturel Franco-Manitobain, and the Royal Canadian Mint. He won a Canadian Heritage Award for his post-1968 fire revitalization of the St. Boniface Cathedral. He received the Order of Canada in 2010, and the Order of Manitoba in 2012.

His work was largely influenced by, and created for, Manitoba’s Francophone community.

The Winnipeg Architecture Foundation announced his passing as a huge loss for Canadian architecture.

“Not only was he one of the most important architects in Manitoba history and probably the most famous Manitoba architect, but I would put him, in the 20th century, in the top five most famous Canadian architects,” Jeffrey Thorsteinson, a researcher with the WAF, said Saturday.

After receiving a Bachelor of Arts degree from Université de Saint-Boniface and an architecture degree from the University of Manitoba, Gaboury travelled to Paris to study at the École des Beaux-Arts in 1958. He found himself influenced by what the WAF calls the “spiritual impact” of early modernist architect Le Corbusier.

Gaboury brought that inspiration home with him, and transformed the curved form and unique interiors he saw in Paris into a style that was distinctly Manitoban while keeping the province’s flat landscape and regional identity in mind.

“He does things like, his windows are often inset, so it’s very prairie-oriented,” Thorsteinson said. “In the wintertime, you’ll get the sunlight coming in because the sun’s lower on the horizon, but because of those inset windows … in the summer, it’s shadier inside.”

Gaboury found early success, earning accolades from spectators of his work and his peers in the field.

“Talking with other architects who were much older than me, but younger than him, that he was the guy that they all followed. And when they wanted to do a prairie thing, they were really thinking of him,” Thorsteinson said.

In 1970, Gaboury received a medal from the Manitoba Historical Society in recognition of his work. He was 40 at the time, young for an architect to be so accomplished, said historical society head researcher Gordon Goldsborough.

Some of his work is so iconic it’s found on postcards and tourist trinkets — the Esplanade Riel bridge, for example — but some of his most beautiful work is hidden away in rural Manitoba, Goldsborough said.

“He’s well-deserving of accolades for his work around Winnipeg, but I would submit that there’s lots of work beyond the boundaries of Winnipeg that warrant people’s attention,” he said.

He remembered a time where he was visiting an abandoned school in the small community of Mariapolis and was struck by its beauty before he even realized Gaboury had designed it early in his career.

“His work runs the gamut, from things that are in active use, to things that are up for sale, and one that’s even abandoned, sitting, vandalized and forlorn,” he said.

With Gaboury’s passing comes the fear that if his work is not properly archived, his legacy could be lost to time.

At the U of M school of architecture, the impact of Gaboury’s simultaneously unassuming and brave design should warrant more of a push to archive and maintain his work, U of M architecture department head and professor Brian Rex said.

“The faculty here is mature, let’s say, so we don’t have those young scholars right now who would be here ready to catch somebody like Gaboury’s work and turn it into a book, which there should be,” he said.

Gaboury and other architects from his time took risks that are still revered today by architecture students and educators, he said.

“There’s a long history here of very material-focused and process-focused architects, and he’s probably the most extravagant example of that, in the way that all the things he did were always pushing materials to the limits and trying new form with material,” he said.

When architect Wins Bridgman arrived in Winnipeg over 20 years ago, one of the first things he did was go see the Marcien Lemay sculpture of Louis Riel, which sat on the Manitoba Legislative Building before being moved to the Université de Saint-Boniface, and the walls Gaboury designed that surround it.

It was an emotional moment for Bridgman, and a profound introduction to Gaboury’s vast body of work.

“In that, I saw a landscape, and a human being, a social injustice, a deep understanding of how the Métis had been robbed of land where Winnipeg is, and how carefully Étienne had both revealed that and also contained it within the beautiful closure,” he said.

They had connected many times, and Bridgman remembers him as character who he admired for not being “necessarily easy to be in a meeting with.” He fondly recounted a time where, at an event where Gaboury received an award after his retirement, he was asked if he missed the work.

“He said, ‘I was kind of surprised by how easy a transition it would be into just living a happy life,’” Bridgman laughed.

“And all the architects of the room just laughed and laughed, because we all knew that behind those words was a whole history of exploration, of thinking and working in an environment that was complex.”

That environment was one Gaboury had to navigate as a tireless fighter and supporter of his own unique style, even after finding early success, Bridgman said.

“Can you imagine how he produced this work when every other architect in the city was not embracing these ideas? And these ideas were, in the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s, suppressed?” he said.

“He was recognized across Canada as a lion, as a huge, huge architectural force, but it didn’t mean that he received commissions throughout Winnipeg. It was very much that he had to fight for what he did.”

Regardless, Gaboury’s work remained distinctly Manitoban to the end, Bridgman said.

“It is both shocking and delighting, (the) exploring that Étienne did,” he said.

“In each situation, there is a certain amount of pain and growing and hopefulness that is about our prairie experience.”

The Free Press spoke with Gaboury in 2014 on what he hopes people take away from the buildings and structures he designs.

Here is a collection of some of Gaboury’s work and achievements.

History

Updated on Saturday, October 15, 2022 2:55 PM CDT: Corrects address to River Road from River Ave.

Updated on Saturday, October 15, 2022 5:57 PM CDT: Updates story with quotes and information

Updated on Saturday, October 15, 2022 6:33 PM CDT: Corrects spelling of Centre culturel Franco-Manitobain