Newcomer mental health topic for early discussion

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 11/10/2022 (1152 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Bushra Awwad remembers feeling sad and scared when she arrived in Canada in December 2016. Born in Syria, she, her parents and four siblings were forced to move to Jordan after the war began. They were there for five years before coming to Canada.

“I didn’t know how to talk and explain what I wanted,” said Bushra, 15.

Being able to speak about mental health early on in their settlement journey is an important need for newcomer youth, according to Seven Oaks Immigrant services, a non-profit assisting newcomers in the northwest Winnipeg area.

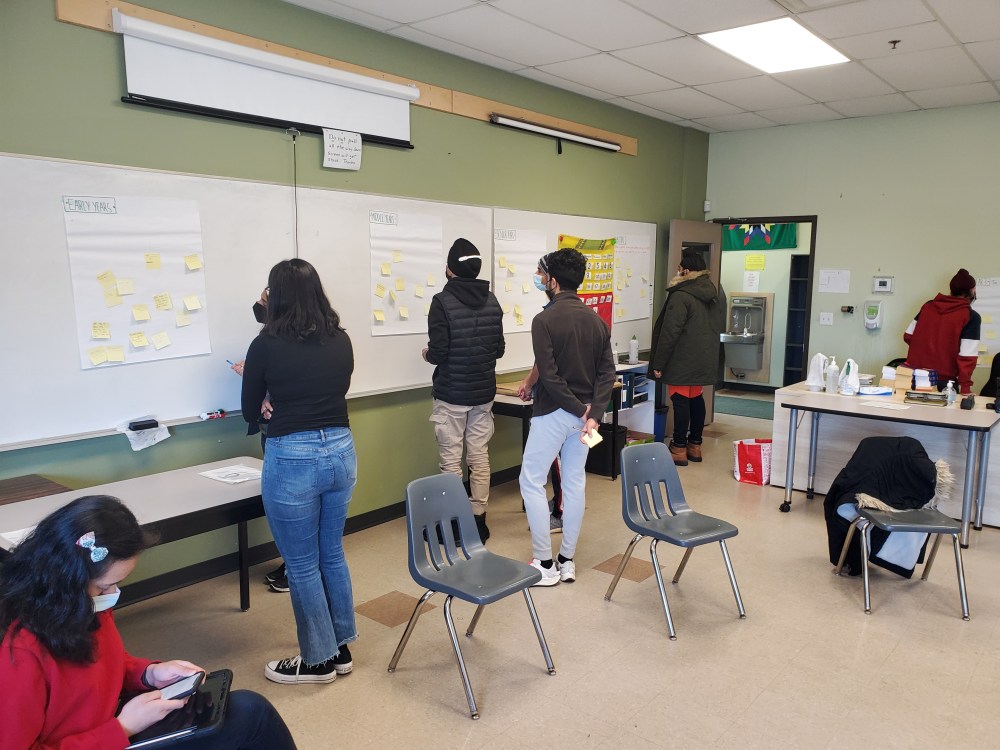

This was one of the key findings from two focus groups Seven Oaks conducted with 20 newcomer youth.

The first group took place in the Maples area in February-March, with youth participants from Grade 8 to age 20, primarily from India and the Philippines. The second group, in June, was held in collaboration with the Newcomers Employment & Education Development Services (NEEDS) Inc. and included participants in grades 9 to 12 from Syria, Iraq and Iran.

“One thing that came out across both groups is that they want mental health talked about early on when they arrive in Canada,” said Manpinder Dhillon, co-coordinator of the Settlement Workers in Schools program at Seven Oaks.

“This isn’t something we’ve got to wait (for), this is something we’ve got to do right away, understand the terminology. Because a lot of them either never discussed it back home or there aren’t words in their language to even refer to mental health or it is seen as a stigma.”

Bushra remembers in Jordan, mental health was not discussed outside of the home. Even though she no longer feels the fear of her initial arrival, she would like to learn how to support herself with various other emotions that may come up.

The focus groups gave youth an opportunity to share coping strategies, says Dhillon, including the unique idea by a Grade 11 participant of keeping a reflection jar.

“At nighttime, before they went to bed, they would write something down, they put it in the jar, and if they ever wanted to look back on it, they always knew where they could find it,” he said. “And they would always look back on it when they needed something either to lift them up or just see what was going on recently.”

This kind of creativity inspired Dhillon and program manager Jana McKee to reflect on how they could offer newcomer youth additional support around mental health. Ideas they are currently considering include offering a day-long workshop on mental health which would include relevant terminology and distributing creative mental health kits with items such as painting supplies.

Although students reported a high sense of belonging in their schools — 90 per cent and above — Dhillon says they did not feel the sense of trust to be able to share their mental health concerns with teachers, worried this would be shared with other teachers or their parents.

Teachers are often the source of the problem, according to McKee.

“Students would say their teachers talk about mental health. But a lot of the stress or concerns around mental health students actually get is because of that teacher, is because of school and (the) classroom. The pressures around it, whether from the educational system, or whether from family and friends,” she says.

“The students would often say, if teachers can talk about it, why can’t they actually start to address it? Why can’t they reduce the homework or why can’t they change it?”

In McKee’s view, more advocacy work is needed to further educate teachers.

Bushra echoes this sentiment. Although she feels welcome in her current school, she did not experience that at her first elementary school in Canada.

Students were saying “bad words” to her, Bushra said, but she didn’t tell the teacher. When she finally spoke up, the teacher told the students to stop. Bushra says it’s important both parents and teachers receive more education around how to prevent discriminatory behaviour against newcomer youth.

The importance of having “a buddy system” within schools to provide support for newcomer youth was another significant discovery from the focus groups.

Although Seven Oaks had thought about this in the past, McKee says multiple youth bringing up this idea highlighted its value. Some of the youth shared they had benefited from this orientation structure when they first started school in Canada, and in a few cases, remained friends with their buddy afterwards.

Once youth are further along in their journey, they can forget what it was like to be a newcomer so this kind of system can also foster empathy, encouraging them to take action to welcome other newcomers, says McKee. Although some schools have this type of a buddy system, in her view, further advocacy work is needed to encourage its implementation across the board.

This story was written for the Winnipeg Free Press Reader Bridge as part of a partnership with New Canadian Media

fpcity@freepress.mb.ca