Running to conquer and reclaim

In 1967, Bittern trudged 80 treacherous kilometres as punishment. This year, he retraced the route to honour those who didn’t make it home

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/09/2022 (1172 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The winter winds were howling and snow was falling in 1967 when Charlie Bittern was tossed from the car and forced to run.

He’d done nothing wrong. But that didn’t matter to the principal of the Birtle Indian Residential School, who was chauffeuring the 19-year-old and his friend Bernell home after a trip to the Royal Agricultural Winter Fair in Toronto, where a bull the two raised was entered in competition.

The ride home should have been celebratory.

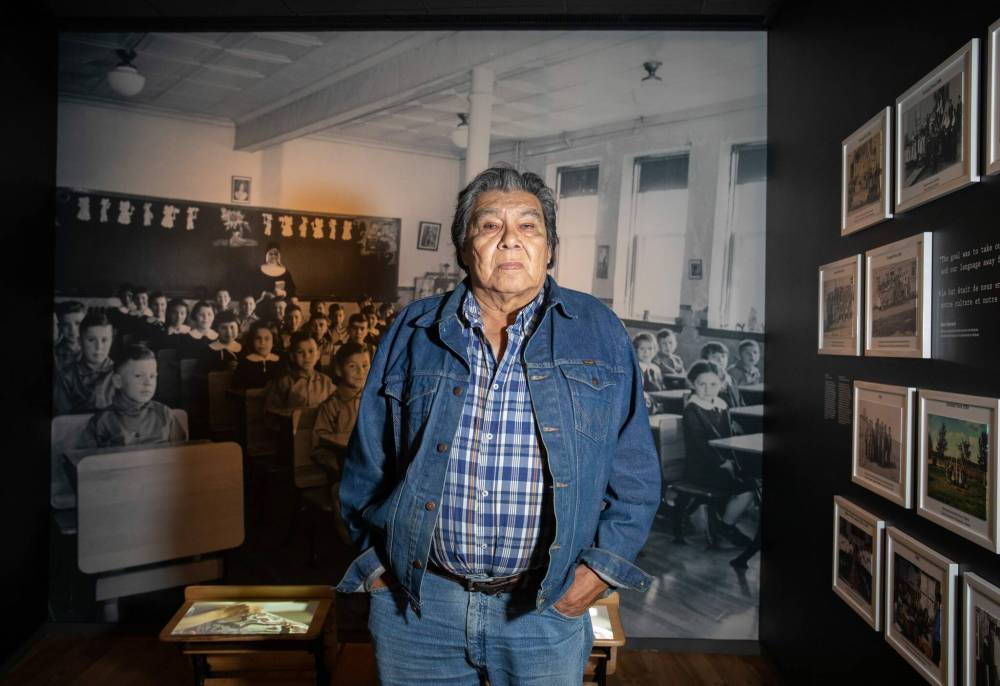

JESSICA LEE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS ‘I felt light.’ Revisiting the traumatizing 80-kilometre run, this time accompanied by an elder, family and friends, was a liberating experience, says Charlie Bittern, here at the Canadian Museum for Human Rights where the documentary about his experience, Bimibatoo-win: Where I Ran, will be screened today.

At Birtle, where the students farmed, Bittern took Bernell under his wing. In a place like that, meant to destroy both the person and the people, sticking together was a matter of survival.

It was nighttime on the highway. The two boys were sitting in the backseat when Bernell passed gas. He giggled, but the driver was not amused by the aroma. The principal turned around and screamed as though a crime had been committed. Such rage was usually reserved for moments of peril, not innocent flatulence. “Which one of you did that?” he screamed. “Which one of you did that?”

Bittern looked at Bernell. He knew a punishment was coming — the principal had a reputation for brutality — but didn’t know what it would be. He had a responsibility to take the rap and spare his friend the brunt of the principal’s ire, so that’s just what he did.

The next thing he knew, the grown man grabbed the growing boy. He threw Bittern to the ground at the roots of a great tree, pointed ahead, and told the teenager to lead the way back on foot.

“You’re a marathoner, aren’t you?” the principal asked.

In his sweats and hoodie, Charlie Bittern started running, the station wagon nipping at his ankles as evening turned to night.

He ran all the way from Portage La Prairie to Brandon.

Eighty kilometres in a blizzard.

Even at age 75, it’s not easy for Charlie Bittern to talk about that night. “My lungs were burning, and my legs were going numb,” he says. All he could think about was survival.

JESSICA LEE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

‘No matter what the government has done to us through the residential school system, we will never die out,’ says Charlie Bittern.

He can’t forget it: he has scars on his right calf, the result of the station wagon driving into him while he dodged snow drifts. He rolls up his jeans to show the reddish marks. Whenever he tried to rest on the hood, the principal put his foot on the gas to nudge his guide forward.

Bittern hardly ever spoke about it. But last November, his friend Wilma saw the tree near Portage and sent him a picture. Bittern, who comes from Berens River, contacted the late elder Dave Courchene Jr., who advised him to go back to the tree. Bittern listened, and saw the branches going in all four directions, and on the tree saw yellow, black, red and white.

“I was reading the truth of the tree,” he says. “And I heard a voice saying, ‘Erica.’”

The Erica in question was filmmaker Erica Daniels, who’d interviewed Bittern for a film a few years earlier. He’d confided in her the story of his run, and shortly after he visited the tree, Daniels sent Bittern a message. The CBC was interested in producing a documentary about that cold November night.

The resulting film, Bimibatoo-win: Where I Ran, should be required viewing. In 22 minutes, Bittern’s storytelling, along with scenic re-creations of his terrible night, depict in stark imagery the depths of cruelty at the heart of the genocidal residential school system. Also incorporating footage from Bittern’s journey down the same highway shot in June 2022, Daniels and her production team have crafted a portrait of resilience, survival and reclamation.

“This is all about sharing a truth, and focusing on the healing journey,” says Daniels, who is Cree-Ojibway from Peguis First Nation. “The reclamation is key. We want to inspire other survivors to have the strength to share their stories and heal.”

Until recently, Bittern said he thought he’d already healed. But memories of his punishment, and other trauma he witnessed at residential school, kept recurring.

During the walk in June, Bittern was joined by his family and friends, including a 96-year-old elder, who with Bittern traced the path he trudged down as a 19-year-old.

When he was forced to run by the sadistic principle, he felt scared, dehumanized, terrified of what was to come. But when he ran in 2022, he says the feeling was different.

JESSICA LEE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

Charlie Bittern confided in Peguis First Nation director Erica Daniels and the result is the film Bimibatoo-win: Where I Ran.

“I felt light,” he says. “This thing that was bottled up inside me, I finally released it.” He felt grateful that his grandchildren and future generations would never go through the pain he went through. He thought about Bernell, who he didn’t see again until 2010, when he visited Bittern to say thank you.

He thought about those kids who ran away, and those who didn’t survive. The unmarked graves that have been, and will be, discovered. “Each one is a brother or sister,” he says.

When he passed the great tree, he looked to the ground, and saw the massive network of roots anchoring it to the earth.

“No matter what the government has done to us through the residential school system, we will never die out,” he says in the film. “We are rooted down to this land called Canada, no matter what the government has done to get rid of the First Nations people.”

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.