Rising to the occasion The Donut House celebrates 75 years of making Winnipeg sweeter, one baked good at a time

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for four weeks then billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/09/2022 (830 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

“Where have you been all my doughnut-lovin’ life?”

A woman who received a box of treats from the Donut House as a gift recently made her way to the North End mainstay from her home in St. Vital, looking to scoop up something similar for a friend. Upon her arrival, she informed Russ Meier, who succeeded his father Erhard as the bakery’s owner in July 2020, after the elder Meier died at age 85, that this was her first time in the store.

“How long has the shop been around?” she asked, gazing into the glass display case.

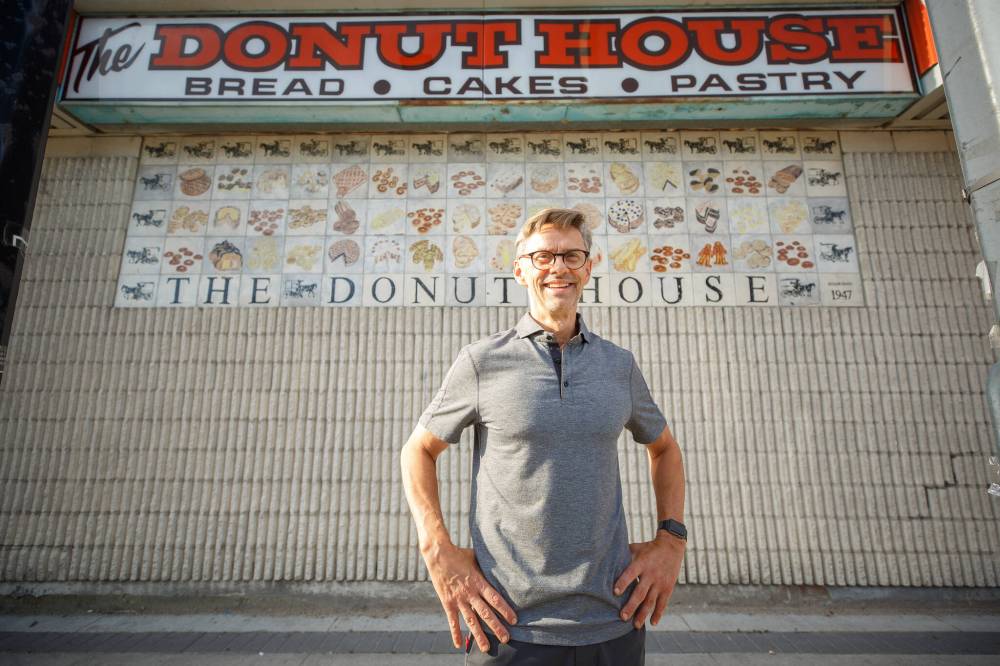

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

Russ Meier succeeded his father Erhard as the Selkirk Avenue bakery’s owner in July 2020.

When he told her the Donut House — recognizable for its bright orange roof — got its start in 1947, she stared back at him like he was pulling her leg, says Meier, seated near a framed photograph of his father, who was still reporting for work every morning, right up until the day he suffered a fatal heart attack.

“She said she was in her 70s, had lived in Winnipeg her entire life and never knew we existed,” he continues, breaking into a smile. “’That’s OK,’ I told her, ‘We’ve always kind of flown under the radar.’ But since this year is the store’s 75th anniversary, we’re thinking it’s probably as good a time as any to change that up a bit, wouldn’t you agree?”

In 1947, Alvin Slotin was working as a delivery driver for a local printing company when a bakery owner on his route began dogging him to help distribute his doughnuts. The fellow knew Slotin’s wife managed a small grocery store. He was hoping Slotin, 31 at the time, could get his confections on the shelves there.

“The way I understand it, Dad didn’t think that was a good fit, but because this guy kept bugging him, he finally said, OK, he’d take a dozen, more to get the guy off his back than anything else,” says Slotin’s son Les, seated in — of all places — a Marion Street doughnut shop, together with his brother Arnie and sister Sharon.

Instead of taking the doughnuts to where his wife worked, Alvin, who died in 2001, dropped them off at a William Avenue store his sister ran, directly across the street from an elementary school. All 12 sold out in a jiffy, the second kids got out of class for lunch, as did six dozen more Alvin fetched back and forth to the store that same day.

Before too long, their father was selling the baker’s wares at a number of spots, Arnie says, including a grocery mart on Magnus Avenue owned by one Sam Gilman. Gilman and his dad became fast friends, and within a month or two, each of them had their own doughnut route, in opposite ends of the city.

“What ended up happening was that the guy they were getting the doughnuts from couldn’t keep up with demand,” Arnie says. “And when that happened, Dad started making his own in the kitchen of our home on Bannerman (Avenue), which didn’t go over too well with our mom, who wasn’t pleased with all these greasy doughnuts taking up all the counter space.”

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

Bakery foreman Thuan Nguyen moves some freshly baked muffins off to the side to cool.

Norley Gilman, the late Sam Gilman’s son, picks up the story from there. By 1952, the pair had outgrown Slotin’s abode — that’s right, before becoming the Donut House, it was a doughnut home — and went hunting for a facility of their own.

They settled on a building at 500 Selkirk Ave., with the intention of using it for production purposes only, but because the space was zoned as retail, they were forced to open a storefront operation as well, Norley says.

Good idea that, Les interjects. Things became so busy — this was back when Selkirk Avenue was every bit as bustling as Portage Avenue — that they often needed as many as five counter people to fill orders for doughnuts, jam busters and, in time, buns and loaves of bread.

In the mid-1960s, there was a Donut House in practically every corner of the city, Norley says, listing locations in St. James, Transcona, St. Boniface and Windsor Park for starters. Another, in Polo Park near the entrance to Sears, outsold all the others combined, save for the flagship store on Selkirk, Les points out.

By 1975, Slotin and Gilman had centralized things solely to the Selkirk Avenue locale, which, by then, had more than doubled in size. They weren’t forced to close the other stores, Arnie points out; rather, a bread strike increased demand for their product so much that they couldn’t keep up with deliveries to their own places, let alone the larger grocers they were now supplying.

“I think they were just done, and that was the reason they decided to sell,” Sharon says. “For years, Dad had been leaving the house for work by 5 a.m., and not getting home till 7 (p.m.), six days a week.”

“It was the same with my father,” says Norley. “They were just burned out, was all.”

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

Meier waits with a batch of doughnuts that will be boxed and then shipped off to various grocery stores in the city.

Erhard Meier was born in Germany in 1935. The fourth of nine children, he left school in Grade 8 to become a baker’s apprentice in a neighbouring village. One of his older brothers moved to Winnipeg following the Second World War, and in 1954, armed with a passport, small suitcase and a freshly minted baker’s certificate, he boarded a ship for Canada to join his sibling.

“My dad and uncle lived in the North End, and that’s where he met my mom, a nurse, in 1961,” says Russ Meier. Despite his father’s lack of education, he ended up doing OK for himself; he became a regional bakery manager for the Dominion grocery store chain, and in 1975 was being courted by a company that wanted to mass-produce kaiser buns.

His dad considered the offer, Russ says, but what he really wanted was his own bakery, a spot where he could turn out the German-style breads and pastries he learned to make as a teenager.

Upon learning the Donut House was on the market, he headed down and introduced himself to Gilman and Slotin, who, in turn, invited him to work there for a month, alongside them and their employees, to see if it was something he’d be interested in.

Because his father didn’t have the resources to buy the Donut House on his own, he teamed with an acquaintance he knew from church, Joe Knoll who served as general manager. Russ, who studied business at the University of North Dakota, took over as GM in 1987, after his father purchased his associate’s share.

Not that he hadn’t been reporting for work, bright and early, for a number of years already.

“We lived on Parr Street when I was growing up, and there were lots of times when I biked there after a soccer game or whatever to give my dad a hand,” he says. “There were definitely occasions in high school when I pulled a night shift, then headed home to grab a few Zs before leaving for school.”

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

In the mid-1960s, there was a Donut House in practically every corner of the city.

Toward the end of the ’80s, Selkirk Avenue wasn’t the thriving thoroughfare it had once been. The Palace movie theatre, directly across the street from the Donut House, had closed, as had other former destination points such as Oretzki’s department store and Charlie Ward’s Country Music Centre.

No longer able to count on pedestrian traffic to pay the bills, the Meiers adopted a new business plan, turning their 12,000-square-foot facility into a distribution centre of sorts, supplying operations such as hospitals, care homes and school cafeterias with treats from their kitchen.

The model proved highly successful, and they were still going strong when COVID-19 struck.

“When the pandemic hit, our way of doing things was probably the worst you could possibly have,” Russ states matter-of-factly. “We were a food service, dealing with things like airlines and VIA Rail, and all of a sudden nobody was travelling. So there go those orders. We also run a spot in the Garden City mall, the Rolling Pin, and the food court was basically closed. That was Strike 2.”

Strike 3 came in July 2020, when the elder Meier died. Suddenly, even turning the key to enter the building was heart-wrenching for Russ. He was reminded of his father every step he took.

“So yeah, he passes away, business is down a good 60 per cent and a lot of our staff — some of whom had been with us for 25 or 30 years — were only working one or two shifts a week,” he says. “The bonus was, we own our building, we own all our equipment, so it was a matter of going back to the drawing board, and figuring out not only how to survive, but also, what we were going to look like, coming out of all this.”

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

Meier leafs through his dad’s old recipe book.

One of the first things he did was pull out his dad’s old recipe books — the Dead Sea Scrolls, he calls them, given their ultra-weathered appearance.

During the fall of 2020, he, with the help of his wife and their three kids, perfected his father’s tried-and-true recipe for German shortbread cookies. Then, ahead of the holidays, he reached out to multiple business leaders in the city, asking whether they’d be interested in ordering boxes of cookies for their workers, given staff Christmas parties were verboten. When all was said and done, the Donut House had sold a tick over 30,000 cookies in the run-up to Christmas 2020, a number that was surpassed the following November and December, when sales soared to 50,000 cookies.

He didn’t stop there. Russ also developed and began marketing a pair of breads originally created by his dad, an apple-cinnamon variety along with a blueberry strudel. Since January, both have been available at various retail outlets throughout the city, including Sobeys, Save-On-Foods and Red River Co-op.

“It’s funny because before COVID my dad was very much of the opinion of: if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” Russ says. “We’ve since developed a website for the first time ever — he would have rolled his eyes at that, no doubt — and tied to the 75th (anniversary), we’re planning on running a few contests, some specifically geared at attracting in-store customers.

“So yeah, these are exciting times for the Donut House.”

Of course, the question on everybody’s lips is, after being around doughnuts for the vast majority of his 59 years, does he still enjoy the tasty treats?

You bet, he says, though, because he’s a competitive marathoner who has participated in races in New York City, Boston and San Antonio, he does try to limit his intake somewhat.

Baker Lester Villa sprinkles a mixture that includes margarine, pastry flour and fine sugar, onto loaves of apple cinnamon bread that have come out of the proofing oven, before being put into the huge oven to bake.

“Just the other day I was leaving work with a bag of doughnuts under my arm to take home,” he says. “I was about to get in my car when I spotted a gentleman with four young kids at his side and thought, do I really need these?

“Hey, guys,” he shouted. “Anybody want some doughnuts?”

david.sanderson@freepress.mb.ca

David Sanderson

Dave Sanderson was born in Regina but please, don’t hold that against him.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Saturday, September 17, 2022 10:13 AM CDT: Adds name of Joe Knoll