Requiem for an elm After the majestic 110-year-old tree on her boulevard was marked for removal, this Wolseley resident wants to remind us all why trees like these matter

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 15/08/2022 (1302 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Aug. 5, 6 a.m.: I have never been so relieved to see a line of cars parked under my boulevard elm, despite the ‘No Parking 6:00 am — 18:00 Monday to Friday’ signs that went up yesterday. My alarm was set for 6 a.m., so of course my brain woke me at 4:30. I snooze with half an ear open for the beep-beep of tow trucks backing up.

8 a.m.: It starts to rain, the light grey and low. I think, “They won’t cut down the tree while it’s raining, right?” Slowly, people start to move their cars or leave for work. The missing cars aren’t replaced. There is a gap under my tree where someone could park.

“I think I heard a big truck go by,” Mike calls up the stairs. My stomach clenches.

July 21, 1:58 p.m.: I got a text from my friend, writer Kerry Ryan, who lives on the next block of Lenore: “I’m sorry about your elm.”

I was working on an essay about the three million trees in Winnipeg’s urban forest, about green infrastructure and equity when I got her message. I had spent a few weeks immersed in the reports of the Winnipeg Comprehensive Urban Forest Strategy, which has been in the works since 2017.

I ran outside to see an orange dot spray-painted on my 110-year-old boulevard elm, planted immediately after our house was built in Wolseley in 1912. Those orange dots mean that your elm has been diagnosed with Dutch elm disease (or DED) and will be removed.

I looked up to see that there were more flagging branches on the curbside limb I’d noticed in July 2021.

At the time, I’d called 311 and asked for an inspection. The technician told me that he thought the tree had DED but I asked for a laboratory test to confirm his diagnosis. He told me it would be six weeks until I’d get the results, but no one from the city was ever in contact, so I crossed my fingers and hoped that no news was good news.

A year later, I stood at the base of the tree, looking up as grief and anger and sadness pelted down on me, like rain, like elm seed or aphid honeydew.

“My condolences,” I heard from behind me. I turned to see an older man loading tools into the back of his truck, parked under my elm.

Moving in and out of the tree’s shadow, he introduced himself as Derek and the teenager next to him as his grandson Pablo.

Over the next ten minutes, we talked about how quick removal of DED-infected trees is best, because it can prevent the infection spreading to neighbouring trees. We talked about the need for more diversity in Winnipeg’s urban forest, about the monoculture of elms and ashes.

But I was a bad conversationalist, my eyes stuck in the flagging branches at the top of the tree.

8:38 a.m.: I hear and then see a red dump truck drive down the street. I head outside, wanting to see if it parks on the street, so I’m ready when the arborists arrive. It crosses Wolseley. I stand in the long grass of my unmowed boulevard, watching the big truck get smaller, listening to the garbage truck work the back alley across the street between Lenore and Evanson.

9:07 a.m.: I drag a chair to the doorway. And two books I’m reading and my cup of tea. The cool air of a rainy day washes over me, with the sound of parents walking their children to daycare at the community center, neighbours chatting on their screened porch, sirens, and more garbage trucks. The cats are in their usual positions on our screened porch: they’ve got advanced degrees in watching the street, the tree. They look at me with concern. Or is it confusion? I am proud, fleetingly, that we got most of the recycling out this week. The big red dump truck drives by again.

Throughout July, I’d dipped in and out of the State of the Urban Forest report, released as part of the Winnipeg Comprehensive Urban Forest Strategy in May 2021, like it was a wading pool.

Of the three million trees in Winnipeg’s urban forest, about 300,000 are in the City of Winnipeg’s public tree inventory, which the recent State of the Urban Forest report says is largely street trees but also planted park trees.

According to the Trees Please Winnipeg coalition’s analysis, 26,000 trees in the public tree inventory were removed between 2016-2021.

Even worse, in 2020, only 19 per cent of trees that were removed were replaced. And with the backlog, there are as many as 40,600 vacant planting sites around the city.

But it’s one thing to read about the loss of trees, about the threats to the urban forest and what that will mean about the quality of life in our floodplained, heat-islanded, drought-y prairies city.

It’s another to come out and see that orange dot, to realize that there’s a good chance you will lose the tree in front of your house.

That it might be years before you get a replacement tree.

9:36 a.m.: My butt hurts from sitting in one position. The squirrel is chirping from my neighbour’s Manitoba maple continuously at Johnny, my two-doors-down neighbour’s sleek black tomcat, which is sitting in the far end of our boulevard. I’m not sure, but I think I just saw the mobile woodchipper go by. Shit.

9:39 a.m.: I go stand under the tree, leaning up against it. From here I can’t see the flagging branches.

In the days after July 21, when the orange DED dot appeared on my tree, I put in a request on 311 again for a laboratory test to confirm the diagnosis, thinking I had — the tree had — lots of time.

On Aug. 4, the no-parking signs went up on my block of Lenore Street.

The only reason no-parking signs are put up in Wolseley is roadwork or tree removal.

I sat on my steps, looking out at the tree, and called 311 to see if they could tell me which it was. After being put on hold three or four times, the 311 operator told me that they thought it was tree removal.

She sounded uncertain. I felt uncertain, but I resolved to spend the day, 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., with my tree, to keep it from being cut down.

To be clear: if the elm has DED I want it removed as soon as possible, but I am unwilling to let my tree be removed without a definitive DED diagnosis.

Throughout the day, I lean on the word “unwilling” like it was a big old tree.

9:42 a.m.: The third pass of the big red dump truck, DO NOT PUSH written across the back. I feel a surge of adrenaline or anxiety, though my mouth still tastes of tea. Kitty watches me from the porch. There are still enough cars on the street to prevent the arborist crew from parking next to the tree.

9:49 a.m.: Another smaller dump truck arrives and parks behind the chipper up the street, idling. It exhales, hydraulic brakes gasping.

In the 1930s, American naturalist Donald Culross Peattie wrote about elms in his A Natural History of North American Trees:

“A big old specimen will have about a million leaves, or an acre of leaf surface, and will cast a pool of shadow a hundred feet in diameter.”

After Derek and his grandson Pablo had gone, I looked down, at the pool of shadow my house occupied, at the dappled light on the sidewalk.

It’s estimated that the difference between a house shaded by a big tree and one without is three degrees.

We already struggled to keep our house liveable, given the increase in hot and very hot days, attributable to climate change. Given the sky full of wildfire smoke, the drought, and the heat domes we’ve had the last few years.

Besides the wrenching pain of losing the tree, an elder in our neighbourhood, the tree I used to claim was the nicest on the block, I also couldn’t help but wonder: what would our house feel like next summer, when the tree was gone?

10:09 a.m.: I go sit in a curve of the tree where Kitty normally sits on her leashed ‘walks’, waiting. I look at my phone, seeing that I’m going to have to take my daughter Anna to her volunteer shift soon. Mike’s at the office today but maybe I can get him to come home and drive Anna over. I call him, anxiety colouring my voice and he suggests calling 311 again or walking up the street and asking what’s going on.

I put my phone away and take deep breaths to calm myself before starting down the street. I want to appear calm but firm, to let the crew know that I am reasonable.

And as I get closer I see that it’s a mobile tarring rig from Public Works, not a chipper from Urban Forestry or one of the contractors that removes trees for the city. But I still go up to the half-open window on the passenger side and ask, raising my voice to be heard over the engine noise of the big truck.

And they confirm that they’re there for street construction, not tree removal. I am relieved but also still awash with adrenaline. Thrumming.

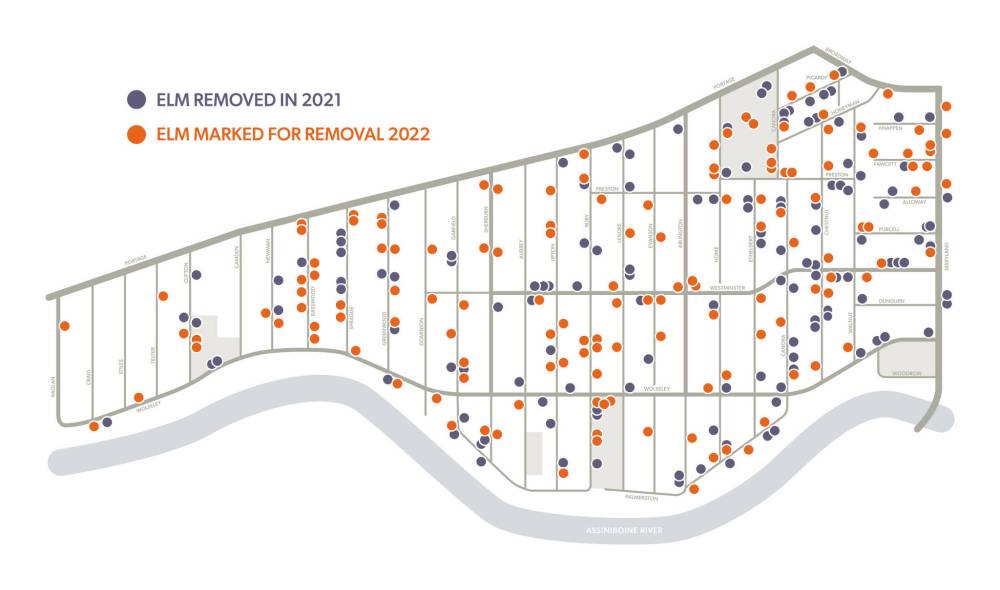

My boulevard elm is one of 3,517 public trees in Wolseley in 2021, down from 4,163 in 2016. According to graphic designer/birder/artist Jeope Wolfe’s census, this year 141 elms are marked for removal in Wolseley.

Joepe notes: “One of my favourite neighbourhood trees, at the corner of Westminster and Dominion, will go. So will the last remaining elm tree on tiny Alloway Avenue, and six trees in Vimy Ridge Park.”

Joepe's elm map of Wolseley.But why do trees and, especially our boulevard trees, matter? Well, trees aren’t just beautiful: they’re infrastructure.

“Trees are City assets just like roads, sewers, and streetlights,” write the authors of the State of the Urban Forest. “But, unlike these hard assets that depreciate in value with time, trees appreciate in value as they grow and age. Trees also deliver more services as they grow.”

What services, you ask? Well, the shade they provide helps reduce energy costs for cooling. Trees also intercept stormwater, preventing it from entering the storm system. They remove pollution from the air and produce oxygen, in addition to storing carbon.

The functional value of those services, city-wide? $53.68 million annually.

But big old trees like mine do more of the work of mitigating the effects of climate change than smaller, younger ones.

We already have a good idea of what climate change will look and feel like, but, for here’s how the State of the Urban Forest report summarizes it, for the record: “climate warming is also associated with increased likelihoods of high winds, flash floods, hail, convective storms, drought, and wildfires.”

MIKE DEAL / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS

Unfortunately, trees are also affected by climate change. They’re also threatened by diseases like DED and insects like the Emerald ash borer, that decimates ash trees and arrive in our city in 2017, by what the City calls urbanization. I call it overdevelopment, especially when it means thousands of trees being removed.

I keep returning to a quote from the June 21 Winnipeg Free Press editorial written by Erna Buffie, the interim chair of Trees Please Winnipeg:

“We stand to lose 50 per cent of our mature canopy — all of our elm and ash trees — over the next 10 to 20 years.”

Never mind my big elm, my little house: what will the city feel like if we lose all those trees?

10:30 a.m.: I get a call from Urban Forestry. They let me know that elm removals don’t start until October, that my vigil by the tree wasn’t necessary.

They say they’ll send someone to collect a sample for the DED laboratory test, and promise that the tree won’t be removed unless the results are definitive.

For another few weeks — and maybe, hopefully, for another few years — my boulevard elm will be one of the 52,000 elms in City’s public inventory, the largest collection of elms remaining in North America.

I get verklempt during the conversation, but not because I’m angry at Urban Forestry — I understand that they’re working with limited resources and have been for many years, given unstable funding from the City of Winnipeg.

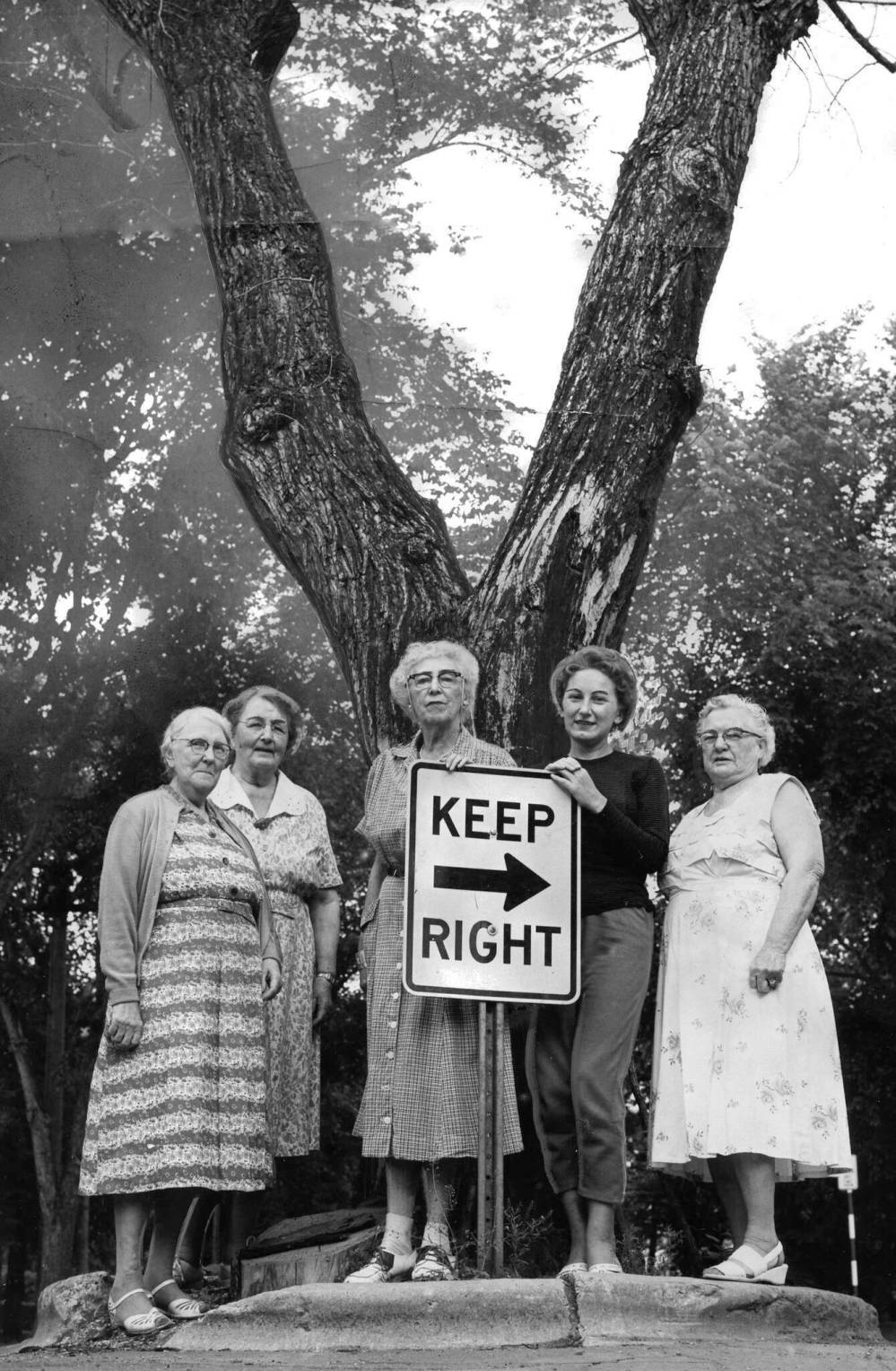

Mrs. F.G. Sheppeard (from left), Mrs. Walter Burman, Mrs. L.F. Borrowman, Mrs. H.H. Roeder, and Mrs. W.E. Johnston. These five ladies were the most staunch defenders of the Wolseley elm when city engineering crews attempted to remove the venerable landmark.At the end of the day, what I want is to live in the shadow of my boulevard elm, to not have to worry about the 3 million trees in Winnipeg’s urban forest.

But that’s not where we find ourselves, this summer, this year, this decade.

When I posted about my tree drama to Twitter, Jeope replied with the famous 1957 picture of a group of old women encircling the Wolseley Elm, which was slated for removal because it was in the middle of the road, inconvenient.

“Bring some friends,” Joepe wrote.

This is a different time, a new battle, but I think Jeope is right: we need to stand up for our trees. We need to protect them, and us.

Ariel Gordon is the author of Treed: Walking in Canada’s Urban Forests (Wolsak & Wynn, 2019), a collection of essays that combines science writing and the personal essay. It received a honourable mention for the 2020 Alanna Bondar Memorial Book Prize for Environmental Humanities and Creative Writing and was shortlisted for the Carol Shields Winnipeg Book Award.