The weight — and wait — of words Wanbdi Wakita has been patiently listening all his 80 years

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/08/2022 (1220 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

It’s a hot summer day and Wanbdi Wakita sits at a patio table on the deck of the St. Andrews home he shares with his wife, Pahan PteSanWin.

The sun is beating down intensely and the air is thick with heat. The sound of birds chirping is briefly interrupted every so often by small airplanes approaching and departing the nearby St. Andrews airport. From the patio table on the deck, you can see a meticulously kept yard with a trampoline, a swing set, and a slide that’s built right off the deck for the grandkids. He has a large family, 12 kids (six who are adopted) and 32 grandchildren.

His voice is quiet, but his words are strong. For him, words are very important.

“We’re not calling ourselves elders, we’re calling ourselves grandfathers and grandmothers. In our language it’s different. Ocinye or Hotokiye (in Dakota), first voices we’re called — ’cause every time they’re (the ancestors) going to talk, it’s always to the old people. So that’s what we go by,” he says.

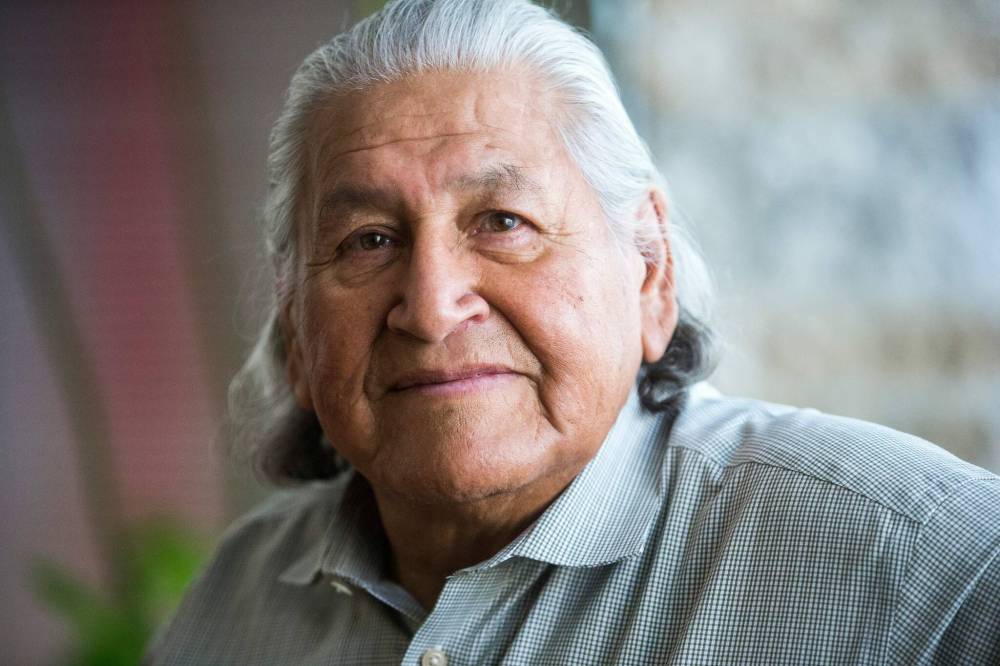

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Wanbdi Wakita, grandfather and knowledge keeper, poses for a photo at Migizii Agamik at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg on Wednesday, July 27, 2022. For Shelley Cook story.

Wakita is a spiritual leader. He has a tipi and lodge on his property where he conducts ceremonies. Sometimes with his family and other times by himself. Ever since he was young, he has been given work by Creator and visions and instructions from ancestors. On this morning, with hot air clinging to our skin, Wakita shares about a ceremony he made the previous day.

“Yesterday I made ceremony for the lightning, the thunder, the rain, the wind. I offered them food. I offered them water. I offered them tobacco. So, I don’t know if you know this or not, we’re in deep trouble with this land. This planet. Deep trouble. I used to say 30 years from now, but I see it’s moving very fast that all people are going to suffer. We’re not listening, that’s why. We’re not listening to Creator. We’re not listening to our ancestors. We’re not listening to Mother Earth. We’re not listening to Grandmother Earth.

“These trees, the wind, the sun, water, fire, everything, belongs to all people. Not only just the Indigenous people. And the ones who are to know more about this living on the land is supposed to be our people, and yet we’re going to the white man’s side and taking up stuff over there. It’s very sad. Very sad.”

The 80-year-old grandfather is from Sioux Valley Dakota Nation, located on the banks of the Assiniboine River in southwestern Manitoba. He is a Sundance chief. Currently he sits on several boards and is the president of Indigenous Veterans Manitoba as well as the grandfather in residence to the University of Manitoba Access Program. He has received many honours, including the Order of Manitoba in 2016.

He is a busy man but he maintains that it’s not too much for him.

“You always have to put into action what Creator shows you,” he says. “Creator doesn’t give me work to get sick or get tired. Creator gives me goodness.”

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Softspoken knowledge keeper Wanbdi Wakita is devoted to the preservation of culture and language and to their proper use. ‘You can’t be playing with this stuff.’

Wakita was one of seven children born in a log farmhouse on Sioux Valley. His mother, Cora, a residential school survivor, gave birth to him while his father, Philip, was away serving in the Second World War. Shortly after his birth, Wakita’s mother received a blue-coloured airmail letter from his father that said: “Glad to hear sonny is born. Give me his name so I can give it to the paymaster.”

Father and son didn’t meet until Wakita was three years old. His father was a broken man when he returned from the war, suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. As a result, they had a complicated relationship for the rest of Philip’s life.

All of Philip and Cora’s children were born by midwife; they all were healthy enough to live a good life until residential school.

“We lived really good, I’m really happy about that strong foundation that my mom and dad built for us,” he says.

Wakita spent eight years in residential schools in Portage la Prairie and Birtle. Many of those days were spent doing hard labour as a farmhand. He left residential school when he was 13. He later joined the military, like his father and grandfather before him. He served for six years, working as a peacekeeper in Germany with the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry. He had four crosses and a crown on his uniform — indicating he was the top marksman in the army. His grandfather had taught him how to shoot, and his dad was a good shot, too.

The path from residential school to the military was paved by many young Indigenous boys.

“Because they had something to prove. The army is probably the only place they talk about discipline, and they run them through the mill. Training is very difficult,” Wakita explains. “But they want to prove something because we’ve been told we’re no good all our lives.”

Wakita says he was an angry man after leaving the military. At that time, he was drinking heavily and had a rebellious streak. He didn’t like being told what to do, and made it perfectly clear one day in 1966 when he punched an RCMP officer in the eye.

In the spirit of reconciliation, the Free Press has been profiling knowledge keepers in the Indigenous culture. Wanbdi Wakita is the fourth to be profiled in the ongoing series.

For the softspoken Wakita the preservation of culture and language is critical. He is strict, yet patient when he shares of himself. There aren’t enough words to capture it all in this interview. The conversation moves quickly, and every so often stops — a long pause, giving way for the words he’s spoken to resonate, and the words has hasn’t spoken yet to formulate. He is steady and soothing when he speaks, every so often drawing out the pronunciation of a particular word for emphasis.

“I’ve been going to ceremonies for a long time. Creator sends ancestors down to me and told me some things. I could hear them. There’s lots along the way. It takes a long time, for me anyway,” Wakita says.

“When I was 17 years old, I was leaving the community. I told my mom, ‘I’m ready to leave’. I was big for my age. My mom said, ‘Before you go, you’re going to get a man name’. So, this old man came, his name was Leo Menard. He was a nice little old man, he really liked dancing. Even when he was 90 years old he’d dance Friday, Saturday and Sunday straight. Lots of people can’t do that,” Wakita says with a chuckle.

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS At 80, Wanbdi Wakita, from Sioux Valley Dakota Nation, is a Sundance chief, president of Indigenous Veterans Manitoba, grandfather in residence to the University of Manitoba Access Program. ‘You have to put into action what Creator shows you.’

“He came, and he done a ceremony for me in our house, and when he finished he said your name is Wanbdi Wakita. In Dakota that means Looking Eagle. He said the Spirit brought you that name, because you look over the people. Make sure everything is OK and if it isn’t, you go help them. Well, right away my thinking is, how am I supposed to help people? I have nothing. I don’t know anything.”

In the years that followed, there have been events in his life and in ceremony that some people would call strange but are regular occurrences for Wakita. He has seen visions and heard voices of spirits and ancestors giving instructions.

“I don’t do things without their go-ahead… without their authority, it’s very important,” he says. “And you have to know your language, ’cause the spirits talk in my language — the old language. It’s hard to sometimes understand. I thought I knew my language. I grew up with my language, but those old spirits they really speak the old language. I’m glad it’s like that. We need to get back. These young people, they shorten the words, and they slang the words, and it isn’t good like that.”

Language is important for Indigenous people. It’s not just the words, but the protection of the culture contained within, Wakita says.

For the Dakota language, he explains, there are different variations. There is the old language that the old people speak, and then the newer language that has slang and made up words that weren’t traditionally part of the language before (words like table or chair), and then there’s the sacred language — only the people who get work from Creator speak this version of the language.

“You’ll learn it if it’s given to you,” he says. “You can’t just speak it any old time. That’s a sacred language. You don’t use that; you just use the regular Dakota language if you’re going to talk to people.

“You cannot have a ceremony if you don’t know your language. How could you have a ceremony? And yet all these young people, that’s what they’re doing. It’s very sad. Very sad,” he says. “What are you going to say when they come and speak the language inside the lodge if you don’t know? How are you going to tell the people inside the lodge that are sitting inside with you. That’s what’s going on. They’re guessing and pretending and it’s hurting them. The people that get hurt come here to get fixed up. They shouldn’t be doing that.”

Wakita shares a story about his adoptive dad — a man who conducted ceremonies and was a Second World War veteran like Wakita’s own father. The man’s only son was a sheriff who was shot and killed while investigating a gas station robbery. The man was struck by how much Wakita looked like his own son so he said he wanted to adopt him.

“I was honoured to be chosen to be his son.”

It was a cold winter day on Dec. 5, 1968, when Wakita’s adoptive father phoned him.

“He said, ‘Light ’em up.’ He spoke Lakota of course. I know what he means when he says, ‘Light ’em up,’” Wakita says. “I went outside. It was snowing and windy. It was like -30. It was like 4-4:30, and it was dark already. I shovelled some snow; dug out some rocks and wood. I made a fire.”

KNOWLEDGE KEEPERS

In the spirit of reconciliation, the Free Press has been profiling knowledge keepers in Indigenous culture.

Wanbdi Wakita is the fourth to be profiled in the ongoing series. Read the previous profiles:

As they prepared for ceremony, another man joined them. He came in search of healing because his knees were no good. Halfway through the ceremony, Wakita could hear something coming inside the lodge. The presence stopped in front of him.

“’Grandson’, he said, all in Dakota. ‘Grandson, build one like this. Use 16 willows, face your lodge to the west.”

The ancestor told him how many rocks to use for each type of ceremony and to sing in order the four songs from the purification ceremonies he’d attended in the years leading up to this moment.

“’Don’t go looking for a pipe, one will come to you,’ he said — I didn’t even have a pipe then. I was just young and going into ceremonies,” Wakita says.

The following March, a man knocked at Wakita’s door. It was a pipemaker from Minnesota.

The man had six pipes for sale, to help raise money for his daughter’s sports team. He told Wakita to pick one of the pipes, which he did, and still carries and uses today as his main pipe.

The following May, Wakita and his two nephews made a lodge, just like the ancestor told him in the ceremony. They went down to the river’s edge, cut 16 yellow willows and started building the lodge, facing to the west.

“I told them about my ceremony that the old man came in and told me to build it, face it to the west, use 16 willows, and acknowledge the morning star and the sun. I told them all about that,” he says. “We had a ceremony right after we finished.

“Those willows inside — they grew, they didn’t die. Those leaves were still growing, it stayed like that all summer. In the fall time, somebody came from The Pas. I don’t know who he was or how he knew, cause I never told anybody. His wife came over and said, ‘My husband is asking for ceremony.’ She said he has a hard time walking.”

They had to help him into the lodge. Wakita made prayers for the man, who was from a different nation.

“All the songs and prayers that we make, he doesn’t understand. But I asked him to make prayers in his own Cree language so I could hear him making prayers. After we finished, and he was able to stand up a little bit. That was the first time I’d ever done a ceremony for somebody, and it helped him. So, I appreciated Creator very much for what he’d done and for his ancestors that came inside the lodge to work on him. I was very thankful to them that they would listen to him when he would ask for help.”

MIKAELA MACKENZIE / WINNIPEG FREE PRESS Sharing a ceremony experience devoted to weather, Wanbdi Wakita says he’s concerned ‘we’re not listening to our ancestors. We’re not listening to Mother Earth.’

That’s how things started for Wakita. Along the way, the ancestors would come. One of them told him to build a tipi and sit inside there with his pipe. “You will be able to help people,” the ancestor said. So Wakita did. That tipi has a blue ring on the top and a red ring on the bottom.

“When I got my name, that spirit said, always mention your name when you make a prayer. And look up. Always look up when you make a prayer, look up. Make sure you do your cleansing with medicine before you do a prayer, that way we’ll be able to recognize you.”

Wakita is strict when it comes to ceremony. He doesn’t go to other people’s. He cautions others to be mindful when participating because there are many who misrepresent themselves as elders and ceremony conductors who have never had a vision or dream, and just copy what other people are doing.

“If a ceremony is not a good ceremony, it’s not going to work. You can’t be playing with this stuff. Creator is going to let you know, you can’t be doing this stuff,” he says. “If you are mad and start walking towards the medicine or a ceremony, it’s not going to work. You will get nothing out of it. I find lots of people are like that. They don’t even like themselves.”

He says that people need to start looking inside themselves for healing so that they can fix themselves. When they do that, he says, Creator is going to start giving them work and instructions.

“When you talk, your ancestors are listening to you, and they’re going to wait and wait and wait until you’re ready and then they’ll show you something. They might, but otherwise they’ll just wait. They’ll look after you. They’ll try and protect you as much as they can, but it’s pretty important.”

shelley.cook@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter @ShelleyAcook

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Friday, August 5, 2022 10:43 AM CDT: adds related stories