Winnipeg’s shiny plan for net-zero emissions

In order to decarbonize by 2050, Manitoba’s capital needs to make big changes. A brand new roadmap lays out the path — now it’s up to the city to see it through

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/07/2022 (1342 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The City of Winnipeg is taking steps toward a net-zero emissions future; a committee of council has unanimously approved an ambitious, multibillion-dollar ‘road map’, with hopes of getting there by 2050.

The Community Energy Investment Roadmap was commissioned by council in 2020. Meant to accompany the city’s broader guiding documents (OurWinnipeg2045 and the 2018 Climate Action Plan), the road map outlines a series of targets for reducing emissions in five sectors, as well as recommendations to help make the goals of the plan a reality. The committee also approved a plan to request annual progress reports from each department affected, and a motion to discuss hiring two additional employees to tackle work outlined in the report at the next budgetary consultations.

Climate and environment advocates lauded the report at a water, waste, riverbank management and environment committee meeting, celebrating its detailed financial modelling and holistic approach to emissions reduction.

“Universally, there is a lot of joy amongst (the climate advocacy) community as a consequence of receiving this report,” Climate Change Connection executive director Curtis Hull said during the June 28 meeting. The road map “is phenomenal; it’s exactly what we need right now.”

Still, the report is only a first step towards reaching the city’s emissions target. More work will be needed to detail how the plan can be accomplished and funded at a municipal level.

What’s in the report?

Winnipeg, like much of Manitoba, relies on hydroelectric power for the majority of its energy , making it one of the cleaner power grids in the country. To effectively curb the city’s emissions profile, the report recommends spending $23 billion over the next 30 years on a “reduce, improve, switch” approach in five key sectors, first reducing energy consumption, then improving efficiency of energy production and finally switching to low-carbon, low-emission energy sources.

The report focuses primarily on the city’s two largest emitters: transportation and natural gas heating.

Transportation accounts for the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in Winnipeg — a city dominated by personal vehicle use and solo car trips. The road map highlights a federal commitment that will require all new car and passenger truck sales to be zero-emission by 2035 — but reducing emissions from vehicles will take more than just electric cars.

The road map recommends fully electrifying transit by 2035, increasing the share of trips made by transit or active transportation by 2050, and electrifying both municipal car fleets and private commercial vehicles between 2035 and 2050.

To get there, the road map outlines recommendations for building denser neighbourhoods with “superblocks” that limit vehicle traffic and ensure residents can access all their necessities within a 15-minute walk. The plan also recommends working with Manitoba Hydro and local businesses to develop charging stations in convenient locations around the city, investing $20 per person in active transportation infrastructure to make walking and cycling a safer and more reliable option, and pushing forward on the existing transit master plan to ensure all neighbourhoods are accessible by public transit.

Homes, businesses, institutions and industrial buildings contribute about 44 per cent of the city’s emissions, the plan notes, with about 93 per cent of those emissions traced back to natural gas heating. Curbing those emissions would require “deep retrofits” to improve energy and thermal efficiency, while also switching to efficient electric heat pumps (which work by exchanging heat from outdoor and indoor air).

The road map recommends retrofitting all residential buildings constructed before1980 by 2035; remaining homes would then be retrofitted by 2050. Commercial and industrial buildings should be retrofitted to improve energy efficiency by 50 per cent and rely on electric heat pumps by 2050. It also recommends substantially increasing the efficiency of new builds by lobbying the province to adopt net-zero building codes over the next three years.

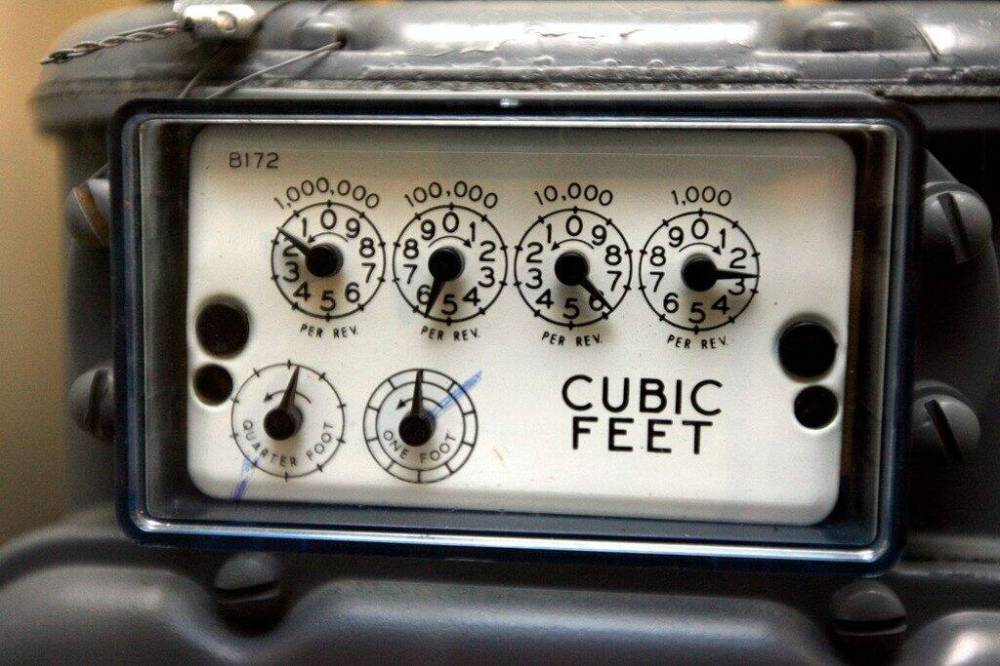

As for other emissions sources, the road map sets a target of 78 per cent waste diversion by 2050, largely through organics collection and a reduction in construction waste, as well as a 25 per cent reduction of wastewater through improvements such as leak detection and encouraging a change in consumption habits.

Shifting to electric power for heating and fuel will put extra pressure on the city’s energy grid. Though efficiency upgrades, particularly in buildings, will help curb some of that increased power demand, the road map recommends diversifying the clean energy grid with rooftop solar power (installed on new buildings, parking lots and in community solar gardens), geothermal district energy (harnessing heat from sewer pipes and ground source heat pumps, for example), and biogas collection from landfills.

By 2050, the road map recommends diverting 100 per cent of methane emissions from landfills for power generation and ensuring 50 per cent of any building’s annual electricity load comes from renewable sources other than hydro, in order to diversify the clean grid.

Where is Winnipeg now?

The road map updates Winnipeg’s greenhouse gas emissions profile with data from the 2016 census, and found that Winnipeggers created a total 4.79 million tonnes of carbon dioxide or equivalent emissions that year, an average of 6.2 tonnes per person. That’s the equivalent of each person in Winnipeg driving a gas-powered car from Vancouver to P.E.I. and back — twice.

Of those emissions, the road map notes 48 per cent come from transportation, another 39 per cent come from natural gas heating in commercial and residential buildings, six per cent comes from waste and five per cent from industrial activities.

Under a ‘business-as-usual’ scenario, total emissions would increase by nine per cent overall by 2050 (though per capita emissions are expected to drop slightly to 4.9 tonnes of CO2 or equivalent emissions due to a decreased need for heating in a warming climate and minor changes to vehicle and building efficiency). The net-zero scenario would bring those emissions down to 0.3 tonnes per capita by 2050.

Laura Cameron, policy analyst with the International Institute for Sustainable Development, said the road map’s overall target of net-zero emissions by 2050 “really can’t be negotiated” if the city is to keep in line with Canada’s commitments under the 2015 Paris Agreement to help limit global warming to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

“It’s really important that Winnipeg is taking that seriously,” Cameron said.

“Certainly it’s not an easy job to figure out how we get there but it looks like, from the priority areas in the plan, that the city is really addressing these big areas — and big opportunities — that come with the transition.”

How do we get there?

The road map recommends a slate of working groups and programs that could help achieve targets set out in each sector. Notably, the road map insists achieving the city’s climate targets will take “full participation from the entire society.”

As part of this holistic approach, the report suggests Winnipeg develop an annual carbon budget — essentially a limit on cumulative emissions the city can create in a given year — to align financial budgets with emission reduction targets. This model is based on the global carbon budget, which outlines the amount of carbon emissions that can be tolerated each year in order to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

The road map also recommends Winnipeg apply a “climate lens” through which all policies and investments can be tested, and that the city track greenhouse gas emissions on an annual basis. Finally, the report recommends expanding the office of sustainability, adding staff who can develop pilot projects, connect with working groups and help decarbonize municipal systems.

The climate lens, which will integrate the road map into all layers of city hall decision-making, has been roundly celebrated by climate advocates. During 2021 budget consultations, Laura Tyler, executive director of Sustainable Building Manitoba, helped spearhead an open letter calling for climate action from the municipality that garnered signatures from more than 90 organizations. The demands of that letter, she said, are covered by the road map.

“One of the things we need to all get better at as a community is working together on things,” said Tyler.

“What’s positive about (the road map) is that it’s not a single issue, it’s something that affects us all. There are all these opportunities for us to work together as an ecosystem to move things along.”

How much will it cost?

Implementing the road map will require a $23-billion investment over the next 28 years, averaging around $800 million annually, or about one per cent of Manitoba’s GDP.

Despite the high price tag, the road map notes the investments pay for themselves “two times over,” generating savings of $53.7 billion through avoided carbon costs, reduced energy costs, avoided maintenance costs and nearly $5 billion in revenue by 2050.

By shifting away from carbon heating and fuel, the report predicts a 56 per cent reduction in energy costs for individual households compared to a business-as-usual scenario.

The shift in energy sources and focus on building retrofits is also expected to generate 103,000 “person-years of employment” between now and 2050, creating opportunities for partnerships with local universities, colleges and trades programs as new employment sectors emerge.

Overall, the road map is expected to net $35.6 billion in community benefits.

Curtis Hull notes the cost of inaction is far greater; as carbon prices reach $170 per tonne of CO2 emissions in 2030, the cost of heat and fuel on individual households is expected to rise accordingly, disproportionately impacting low-income households who may face the choice between “staying warm and staying fed.”

The report also notes climate-related disasters, such as floods, fires and storms, will become more prominent should the climate continue to warm, and provinces will be expected to spend increasing amounts on disaster relief. Already in the last decade, Canada’s spending on disaster costs has increased from one to five per cent of its GDP.

In Winnipeg, the report estimates the cost of climate damages in a business-as-usual scenario could reach $30.5 billion by 2050; in a net-zero scenario, the cost of damages over the same time would be just shy of $12 billion.

What’s missing?

Climate action groups have unanimously praised the report as evidence the city is taking the issue seriously; still, they note the report needs buy-in from community members, the provincial government and the city itself through budgetary support.

“We need to be aware of the fact that it’s not a done deal,” Tyler said. “Until there are people hired and there’s budget allocated, this is just another plan on the shelf.”

Tyler called the road map a “renewed commitment” to climate action at a municipal level, but noted the city will need to move quickly to consult with working groups, lobby the province and begin putting recommendations of the report into action.

On the topic of low-emission buildings, for example, she noted the city will need to to avoid “adding to the problem” by creating new builds that will need retrofitting down the line.

At Climate Change Connection, Hull said the report succeeds in outlining the scope of work that needs to be done, but cautions “it would be naive to think that the city can do this alone.” He noted the city is “hobbled” by provincial legislation, such as outdated building codes and narrow energy efficiency mandates, that will require review to set the road map into motion.

Hull added he would like to see the Crown corporation Efficiency Manitoba manage implementation of the road map, but the corporation is currently limited by its legislated goal of reducing provincial electricity consumption by 1.5 per cent and natural gas by 0.75 per cent annually.

What did the committee decide?

The committee voted unanimously to implement the report, research how to apply its recommendations in financial decisions and to use its analysis and recommendations to update the climate action plan and climate resiliency strategy. The committee is also recommending two new staff positions — a senior planner and a green building specialist — be added to the 2023 budget process, and that the municipal staff office be allowed to find and accept grants (up to $500,000 each) that can help implement the road map.

For accountability, the committee has also approved a directive that would ask departments impacted by the report to prepare annual submissions related to work on the goals outlined in the road map.

These steps mark an ambitious shift in Winnipeg’s city policy, and have given hope to Winnipeg’s climate advocates.

“It’s hard enough to live in the existential crisis of knowing that you’re living on a planet that’s headed in the wrong direction, that we’re destroying this incredible ecosystem,” Tyler said.

“But to watch your leaders do nothing about it is a very specific form of grief. So to have that layer of grief soothed even a little bit is really important, and I’m really grateful.”

What’s next?

The recommendations will need to be discussed at an executive policy committee meeting before being presented to council as a whole later in the summer. Budgetary approval for the proposed new staff positions will be considered in the 2023 budget process.

Beyond city council, policy analyst Laura Cameron said now is the time to get communities educated and involved in climate solutions in order to make sure the road map remains a priority for years to come.

“It needs to be able to withstand political changes at the city level, and the city needs to be able to work with different jurisdictions and different levels of government,” she said. “This work is just the beginning, this work needs to be resourced and supported from now to 2050 and beyond.”

julia.simone-rutgers@freepress.mb.ca

Julia-Simone Rutgers is the Manitoba environment reporter for the Free Press and The Narwhal. She joined the Free Press in 2020, after completing a journalism degree at the University of King’s College in Halifax, and took on the environment beat in 2022. Read more about Julia-Simone.

Julia-Simone’s role is part of a partnership with The Narwhal, funded by the Winnipeg Foundation. Every piece of reporting Julia-Simone produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.