Naawi-Oodena an example of reconciliation in action

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$19 $0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for four weeks then billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 27/06/2022 (911 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Treaty 1 First Nations took an important step forward last week in their proposal to create Canada’s largest economic development zone, or urban reserve, in Winnipeg.

A municipal development and services agreement negotiated with the City of Winnipeg was approved unanimously by city council, paving the way for the Naawi-Oodena development at the former Kapyong Barracks site to be designated an urban reserve by the federal government.

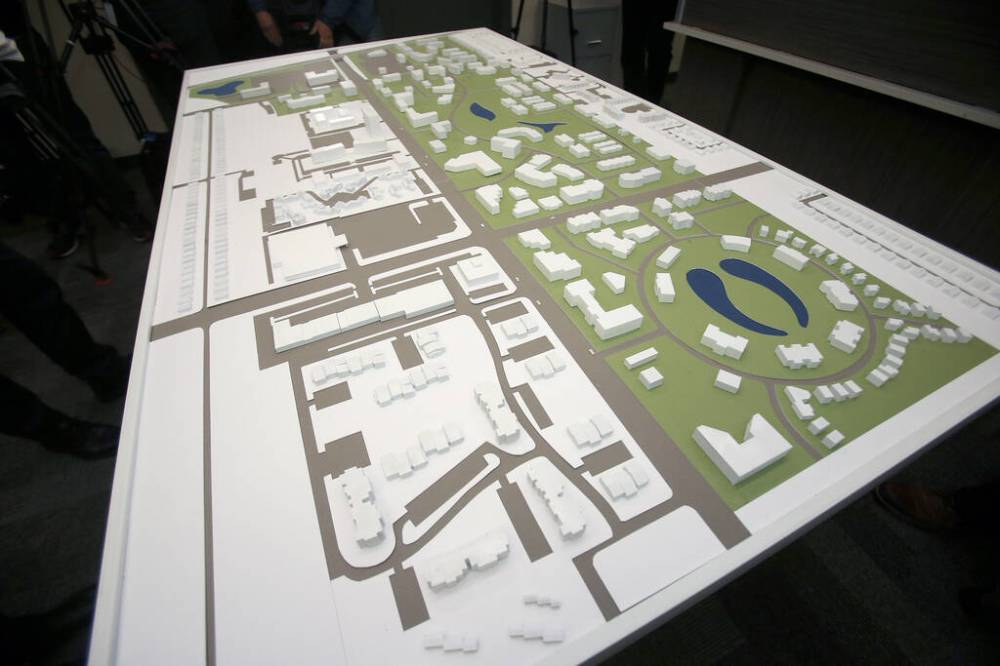

The agreement will see Treaty 1 First Nations develop 68 per cent of the vacant land along Kenaston Boulevard, creating a mixed-use village that will include commercial, retail and residential properties, as well as sports and recreation amenities, a cultural campus and community spaces.

The economic impact of the project will be enormous: an estimated $512 million added to Manitoba’s GDP, including more than 5,000 full-time jobs from the construction of the project alone.

“We’re really moving towards self-governance and recognition and self-sustainability and this development is a huge step,” said Jolene Mercer, director of governance with Treaty One Development Corp.

Under the terms of the agreement, the corporation will levy its own property and business taxes and remit 65 per cent of those proceeds to the city to pay its share of municipal services.

It is a win-win proposition. The development supports the principle of self-determination for Indigenous people and contributes to the reversal of 151 years of neglect by the federal government in fulfilling its treaty obligations. It will also provide Winnipeg with valuable residential and commercial development and much-needed taxation revenue.

There are many examples of reconciliation across the country designed to improve the lives of Indigenous people. The Naawi-Oodena development is one of them.

A century and a half ago, the federal government negotiated Treaty 1 with seven First Nations at Lower Fort Garry on the western bank of the Red River. It was the first of several numbered treaties signed between the Crown and First Nations. Treaty 1 covers most of what is today southern Manitoba, including Winnipeg.

Under Treaty 1, First Nations were promised, among other things, 160 acres of land per family of five in exchange for the peaceful settlement of Manitoba by newcomers. The federal government reneged on that commitment, forcing Indigenous leaders to spend decades in court fighting for their land rights. Some progress has been made on that front through the Treaty Land Entitlement process, although many obligations remain outstanding.

The Naawi-Oodena development did not occur without a secondary legal battle. The federal government, under both Liberal and Conservative prime ministers, refused to engage in meaningful consultations with First Nations after the Department of National Defence announced in 2001 it planned to vacate Kapyong and move the 2nd Battalion Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry to CFB Shilo.

First Nations leaders expressed an interest in obtaining the Crown land under the Treaty Land Entitlement process. However, their inquiries were rebuffed; the federal government insisted the land would be sold through the Canada Lands Company, a federal Crown corporation.

First Nations leaders expressed an interest in obtaining the Crown land under the Treaty Land Entitlement process. However, their inquiries were rebuffed.

Thus began a protracted legal battle that ended in 2015 with a Federal Court of Appeal ruling in favour of First Nations. Ottawa was forced to negotiate with Indigenous leaders and a deal to transfer the land was signed in 2019.

Nothing comes easy for First Nations when fighting for their treaty rights – successive federal governments have seen to that.

What Canadians want today are fewer court battles and more mutually beneficial developments such as Naawi-Oodena, which represents the spirit and intent of the treaties: for Indigenous people and newcomers to live together in peace and harmony and to share equitably in the land.