‘A forgotten genius’ From caricature to religious art, the impact of Jacob Maydanyk’s early 20th-century work resonates as Ukraine’s history of invasion and suffering repeats

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 01/04/2022 (1348 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

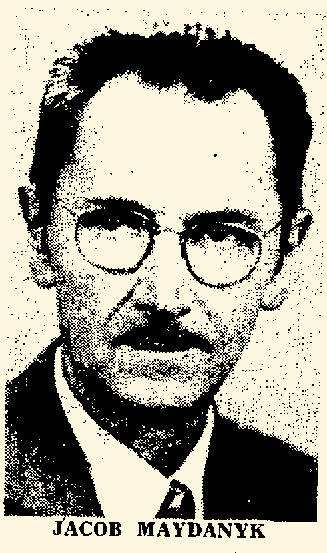

Jacob Maydanyk was never exactly like the others, no matter who the others were. If the Winnipeg Anglo-Saxon elite saw him at all, it was as a Ukrainian, nothing more. To the overseers of the extra gang, he was just another “Jack” working on the railroad for $1.35 per day. When the Ukrainian men working alongside him looked at him, they could sense he was different, not quite a prince and not quite a pauper. Even if wearing the same coveralls as everybody else, the thin man from Svydova with the goatee carried the aura of an outsider.

When he arrived in April 1911 to Manitoba from a country he called Ukraine but which the world did not, Maydanyk made no plans to stay long. The son of a peasant farmer who tilled the soil of an Austrian landlord with little land to spare, Maydanyk was determined to do more instead of making the most of less.

His mother was illiterate but wanted her son to learn. He was gifted, both intellectually and artistically, literate, multilingual, capable, competent, handsome and, despite his lack of financial influence, fortunate.

As a teen, Yakiv — as his friends called him — managed to wrangle an apprenticeship in Rakszawa at a textile academy and became an understudy to a religious iconographer, using paint to illustrate bible text. Despite his father’s belief that art was immoral, he dreamed of studying in Paris; he came to Winnipeg instead.

His studies abroad had put his family into debt, and hearing tell of a booming city way out west with land — better yet, cheap land — to spare, Maydanyk decided to take advantage of the opportunity. Within two days, he was laying rails. But the money was not as quick as he’d have liked, and the labour was not the kind for which he was best-suited: Maydanyk’s greatest attribute was not brawn; it was the other thing.

More opportunity: the province, which had experienced an influx of Ukrainians numbering in the thousands, needed educators who could speak their language and teach them the one they needed to learn to assimilate. Within a few months of his arrival in the new country, Maydanyk enrolled at Brandon’s Ruthenian Training School. Art was an end, and this was his means.

For two years, Maydanyk taught in a series of one-room schoolhouses across the province, mostly in Olha and Oakburn, where many Ukrainians settled. Meanwhile, word of his artistic prowess reached the ears of parish committees, who had newly built churches with naked walls in begging to be dressed in the painted robes of gospels and the saints. In his spare time, Maydanyk devised a most unholy man in pencil and ink.

● ● ●

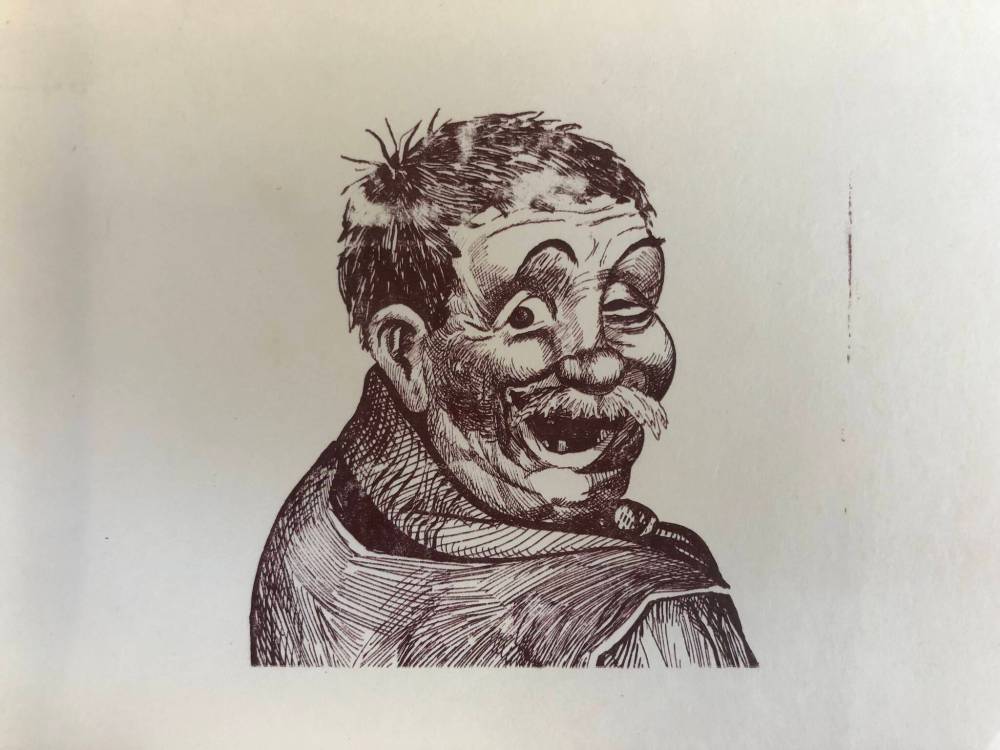

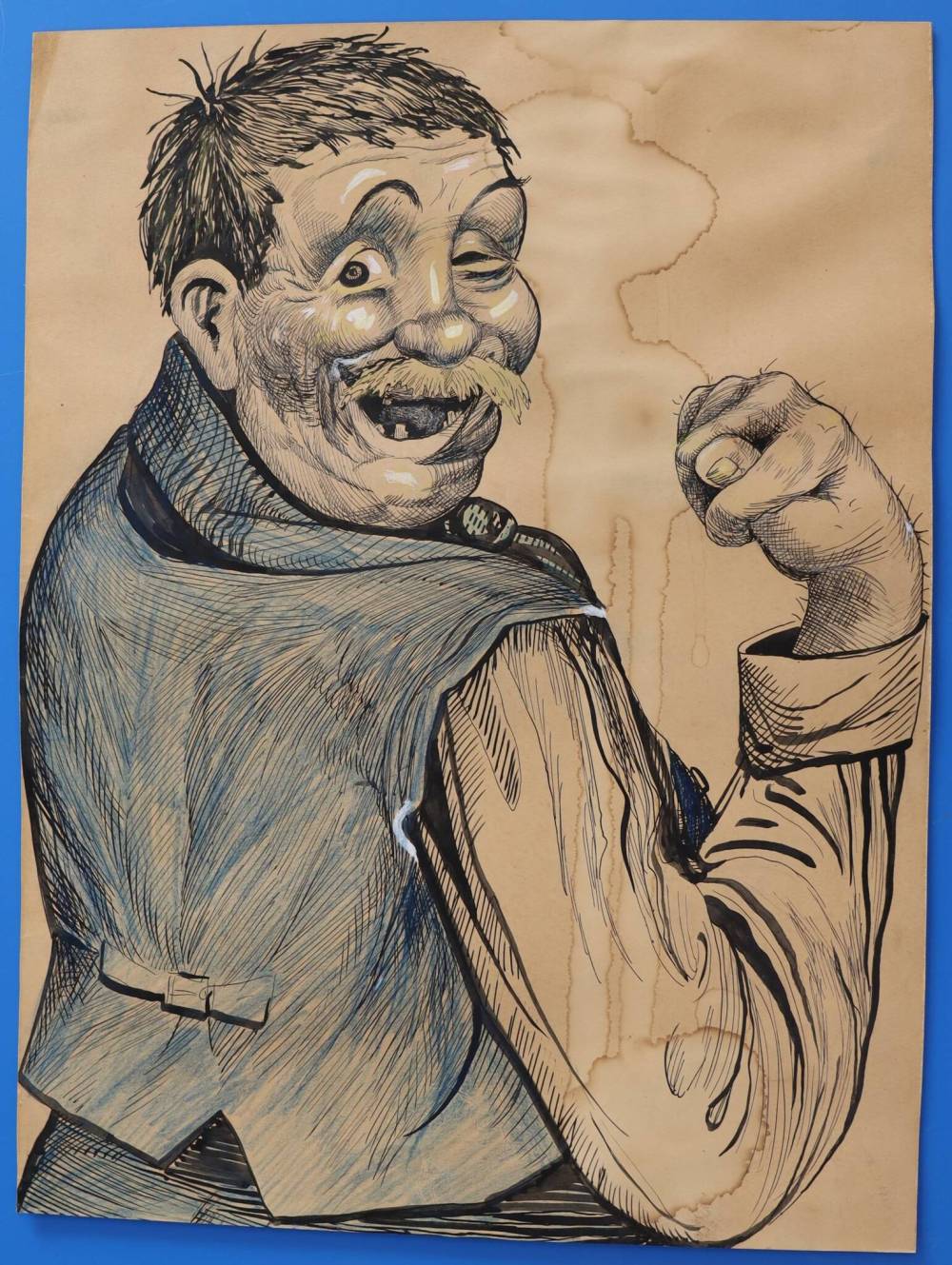

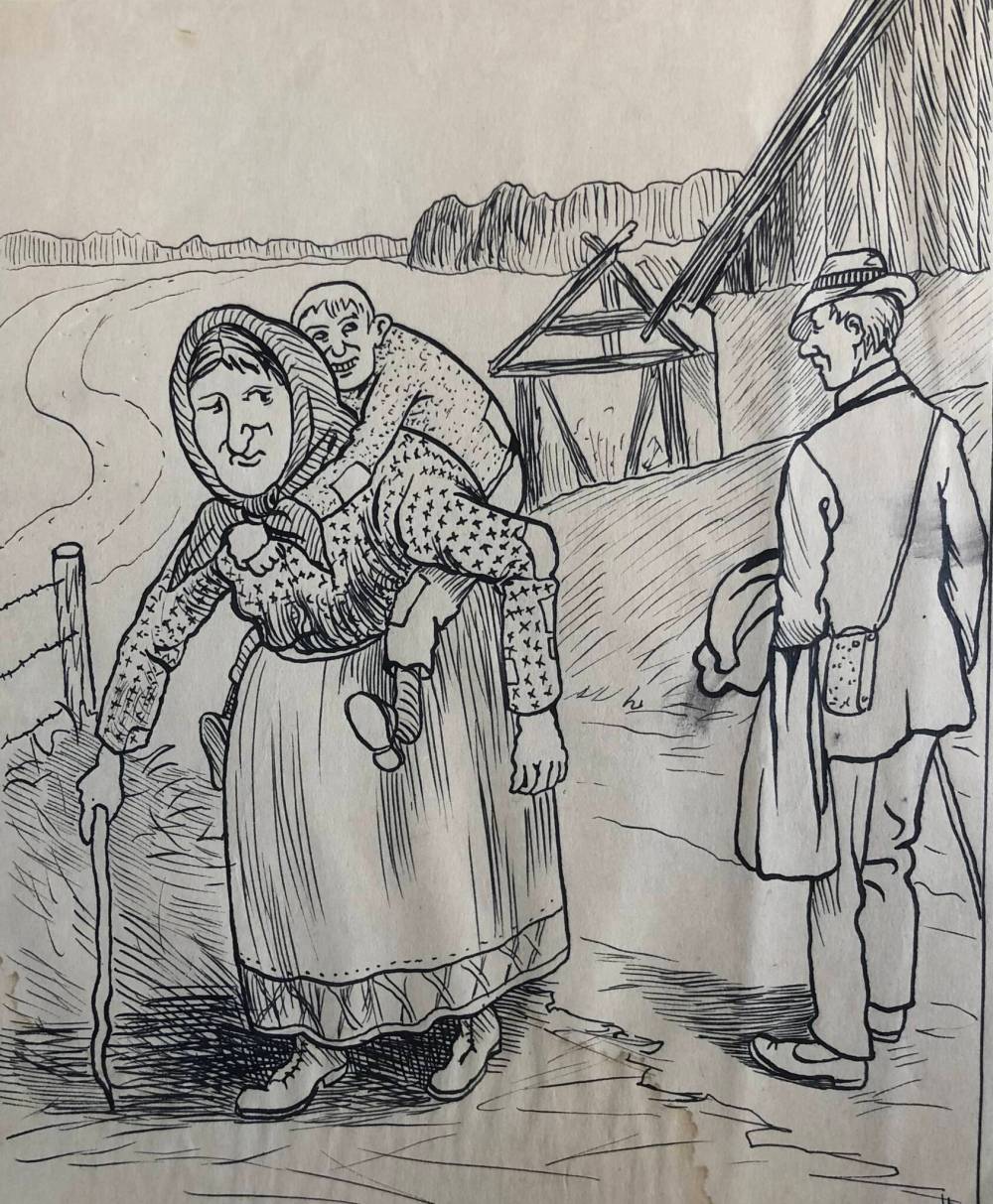

“Vuyko Shteef Tabachniuk” was an oaf. He was uneducated. He was loud. He was fat. He was crude. He was easily confused and quickly angered. As much as he mocked himself, he mocked the new Canadian world he now called home. And he wanted very badly to fit in.

On the surface, “Uncle Steve Tobacco” was nothing like his creator, who always looked polished in his three-piece suits. Shteef’s hair was mussed, and his belly rolled over his beltline like the foam on a pint of over-poured beer. Tabachniuk was an amalgam of negative stereotypes applied to newcomers from Maydanyk’s part of the world, who were routinely and unfairly seen as drunkards and lowlifes in the community at large. But the cartoon also was a lovable depiction of immigrant life at the turn of the century.

Though Maydanyk had Louvre-sized aspirations, and the skills to realize them, it was this caricature of a man who became his most far-reaching contribution to the world of art. Vuyko Shteef was a relatable folk hero to a new class of Canadian citizen, and through self-parody, Maydanyk hoped to point out the hypocrisy of the upper class, prove to his compatriots they were not alone, and show them exactly how not to act.

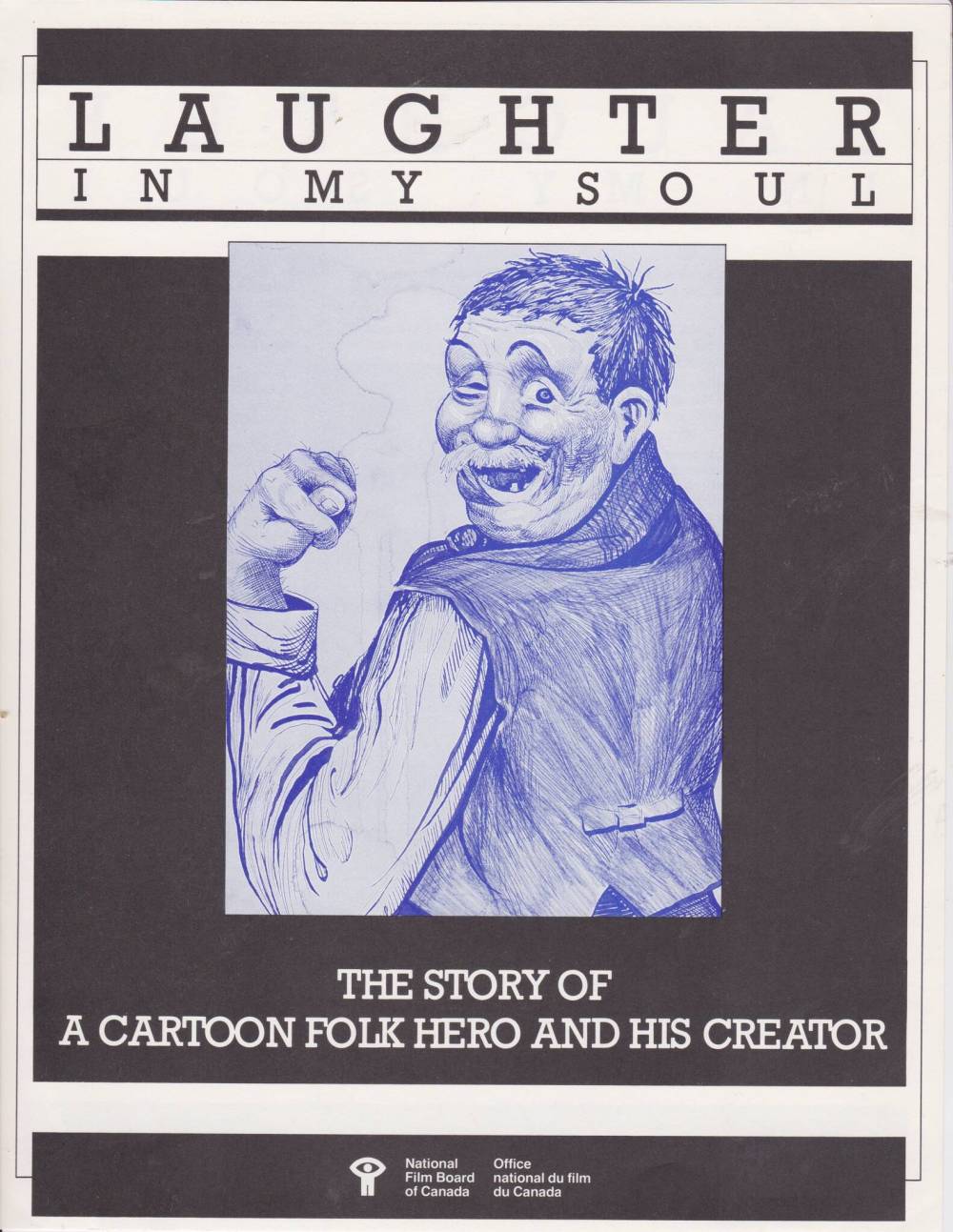

“Young people like to laugh at an old fellow,” the humble cartoonist said in an interview with filmmaker Halya Kuchmij for her 1983 National Film Board documentary, Laughter in My Soul, available to stream at nfb.ca. “In addition to this, you needed to create a Tabachniuk who was fat and did stupid things like them. On the one hand, they laughed at him, on the other hand they tried not be like him. They wanted to be better.”

Tabachniuk was a masterstroke, and his fully formed character was often attributed to Maydanyk’s days on the railroad, which were spent alongside goodhearted men who, like him, were struggling to adjust to a new set of social mores and the isolation of a Prairie life. He gave truth to the phrase comic relief.

The affable oaf spoke in a broken, sloppy vernacular mix of Ukrainian, English, Russian and Polish that echoed the way the men on the railroad conversed. The captions above the comics, some single panel, some more complex sequences, were written as the people who could read them talked. Shteef Tabachniuk was speaking their language.

Artist Larisa Sembaliuk Cheladyn, who is at work on a PhD dissertation on Maydanyk’s life and work, traces the character’s origin to a letter from the old country that found its way into Maydanyk’s hands while he was at the Ruthenian Training School. “It wasn’t the letter so much as the envelope that caught his attention,” she writes. “It appeared to be written in a hybrid of languages — Ukrainian, English, German and Polish — … (and) can be loosely translated as ‘Please — reply — immediately — to the sender — Shtyfan Tabachniuk.’”

Students found the letter funny, and competed to see who could write the best letter, according to Dimitrij Farkavec, a late Ukrainian Manitoban artist Sembaliuk Cheladyn cites. Maydanyk shortened Shtyfan to Shteef, and added “Uncle,” which eschewed fatherly morality and created an intimate familiarity; everyone had an Uncle Shteef, and despite his flaws, he could still be loved.

The first Tabachniuk cartoon Maydanyk got published, in 1912, depicted Uncle Shteef crouched over a writing desk, labouring over a letter to his wife in Ukraine. He wrote English words which appeared in Cyrillic font, mixed in with actual words in his native tongue.

Later comics showed Tabachniuk getting kicked in his rear end by his manager on the extra gang, still struggling in a land where many men expected quick riches and equality. “Jesus Christ,” he shouts as he flies through the air. “This is a free country?”

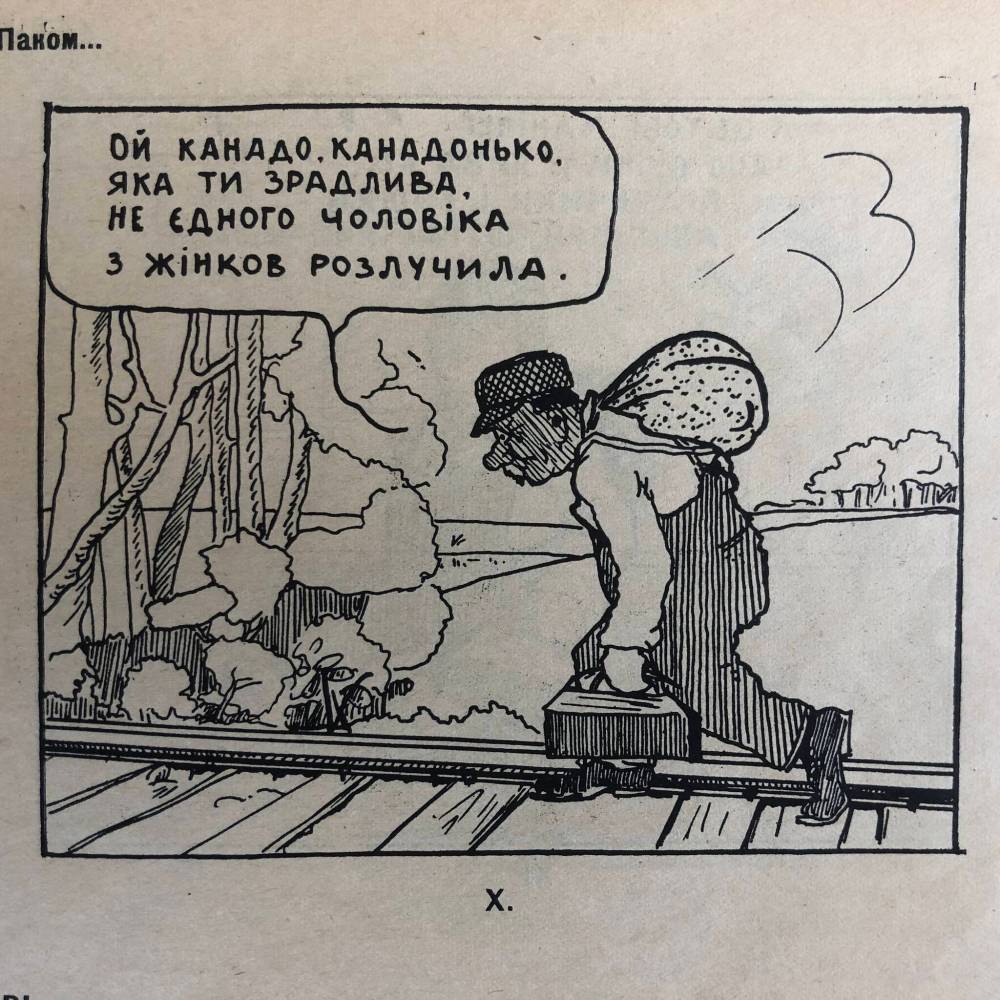

“Oh Canada,” Tabachniuk wails in another as he walks down the train tracks after a long day at work with little to show for it. “You betrayed me. You take so many men from their wives.” Other comics lambasted unsavoury stereotypes, such as one strip in which Tabachniuk spills a bottle of alcohol into an eavestrough while on the roof. Rather than waste a drop, he races to the yard, gets down low and puts his lips to the spout.

Tabachniuk’s grinning face soon graced the pages of some 20 Ukrainian-language newspapers and some English publications across the country, most of them based in Winnipeg. In 1914, Maydanyk moved to the capital city to open Providence Church Goods, a religious supply and small-scale icon-making shop with clients across North America and as far away as Australia.

With new churches popping up to serve blossoming Ukrainian communities, Providence was booming, and Maydanyk employed a small team of artists — including sculptor Leo Mol and artist Theodore Baran — to paint and carve religious icons and symbols. As the community grew, so did Maydanyk’s shop, which likely got a good deal of its business through his friend, Bishop Nykyta Budka.

His comics took on a new tone, poking fun at the bourgeoisie of the capital city, and within a few years of his arrival, he achieved a modest level of celebrity, thanks largely to his monthly “Shteef” inserts in the Canadian Farmer, a Ukrainian newspaper. In 1918, the first almanac of Maydanyk’s humour and satire was published. He would produce seven collections, according to Sembaliuk Cheladyn, along with a standout work: 1930’s Uncle’s Book.

Uncle’s Book is considered one of the earliest comic books published in Canada, though claims such as that are difficult to prove. One thing is for certain: it was a hit. A run of 10,000 copies — printed and published in Winnipeg by National Press Ltd., and its publisher, Frank Dojacek — was reportedly sold out. Sembaliuk Cheladyn thinks that number has been inflated by legend, as a 1970s reprint of the book only numbered 1,000 copies, but her research has revealed copies were sent as far away as Spain and Argentina.

In 1931, there were approximately 22,000 Ukrainians living in Manitoba. Many would have had a copy of Uncle’s Book on their shelves, and knew Shteef Tabachniuk — whom Halya Kuchmij would call “Archie Bunker and Laurel and Hardy rolled into one” in her documentary — as a member of their family.

Maydanyk dabbled in theatre, writing a satirical drama called Manigrula (a combination of Manitoba and the word for immigrant) in 1915, while also painting icons for the new local Ukrainian churches.

Maydanyk established himself as a central figure in Winnipeg’s urban Ukrainian intellectual community. He was not considered a wealthy man, nor a poor one, though he did own an automobile in the 1920s. He did not necessarily want to be considered famous; he cared about his art and his shop and his friends and his family. His passion was not defined by the public’s reception.

“I call him a renaissance man,” says Olesia Sloboda, the curator of collections at Winnipeg’s Oseredok Ukrainian Cultural and Education Centre, where Maydanyk’s drawings and personal effects are stored.

But as Maydanyk got his first taste of artistic success in the 1910s, his former home was besieged by war, enemy forces circling, a tale as old as the land his father sowed.

—

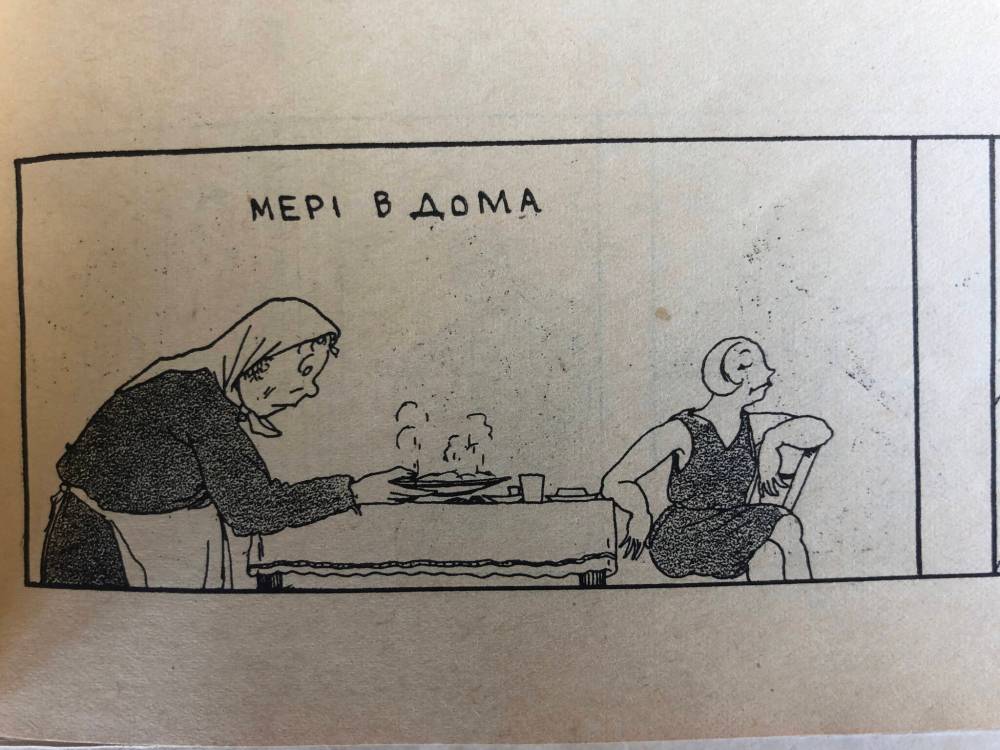

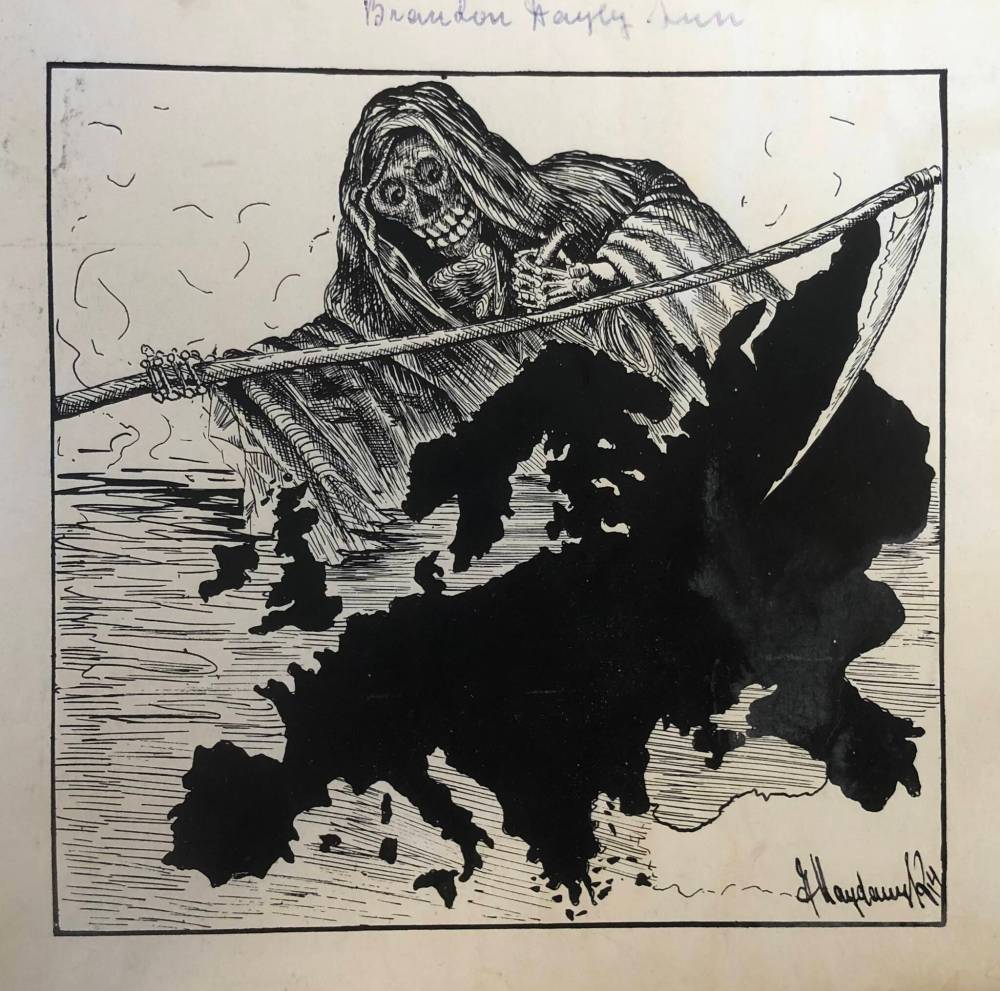

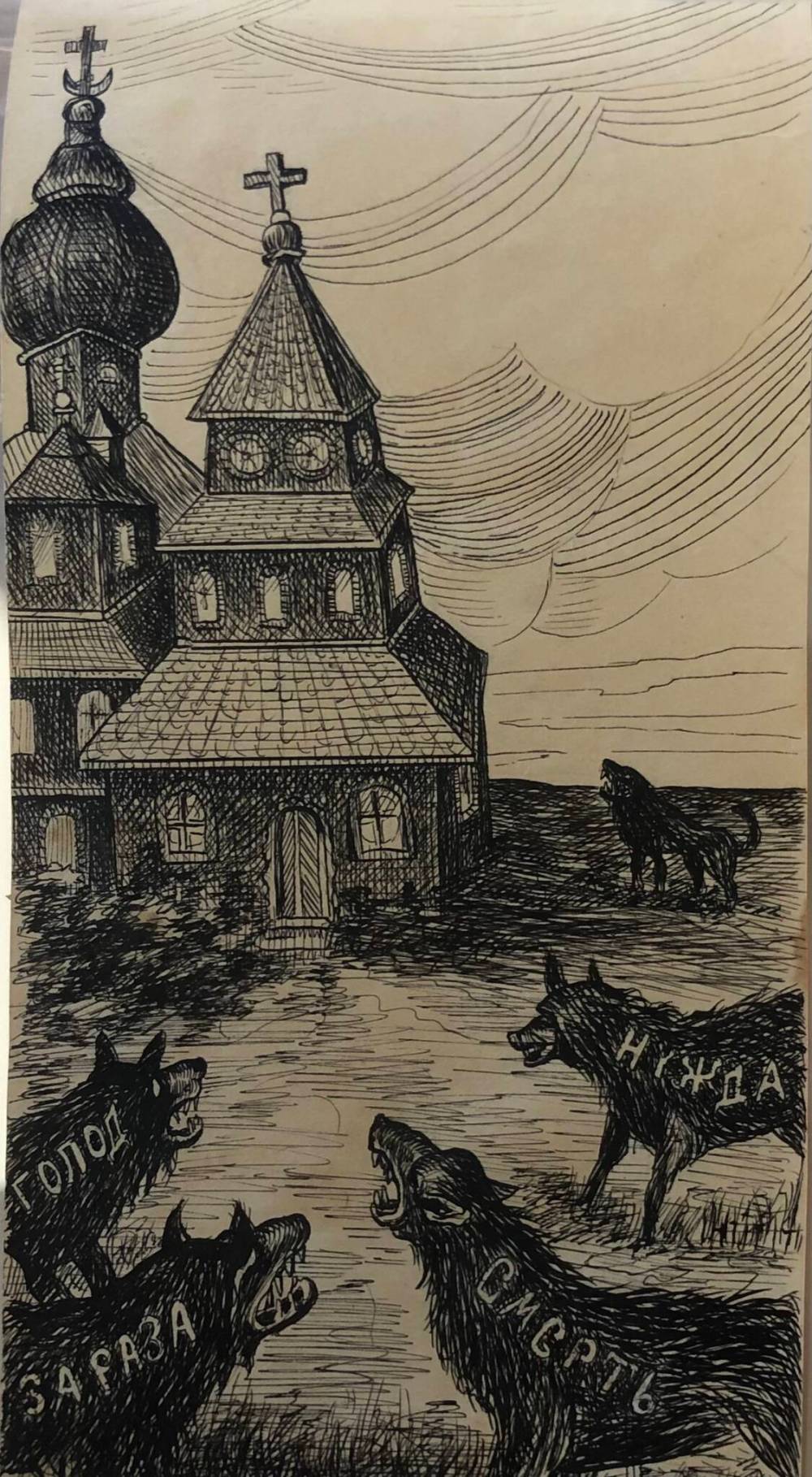

While Uncle Shteef and a later creation called Our Mary — who put the experiences of Ukrainian Canadian women into perspective — were his calling cards, Jacob Maydanyk was producing serious political cartoons for papers including the Brandon Daily Sun.

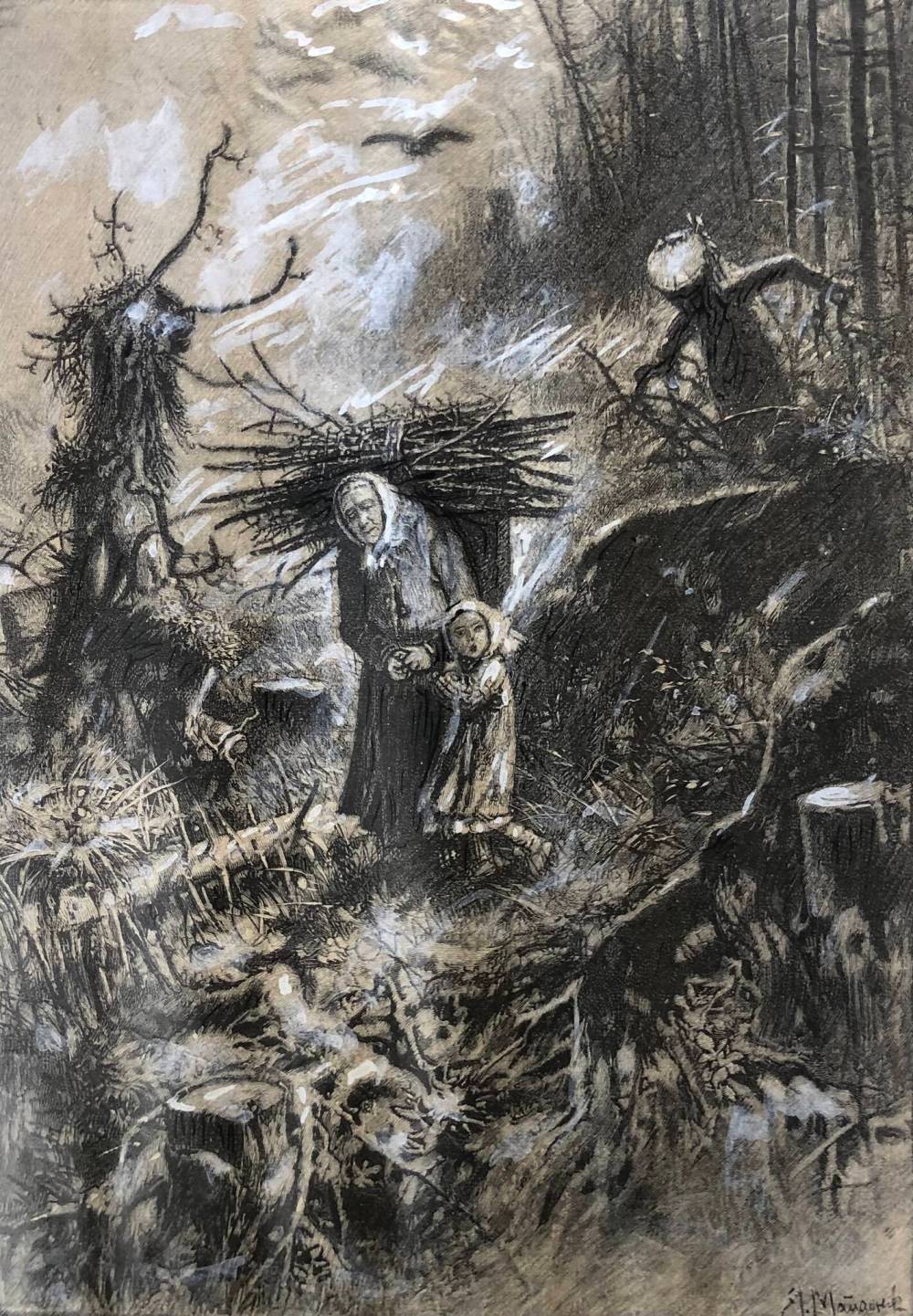

These did not poke fun. They also did not pull any punches. With a Gothic flair, they showcased the desperation of a distant homeland, which for centuries knew nothing but persistent threats to its sovereignty and mere existence, which now presented themselves yet again in a war deadlier and more advanced than any which preceded it.

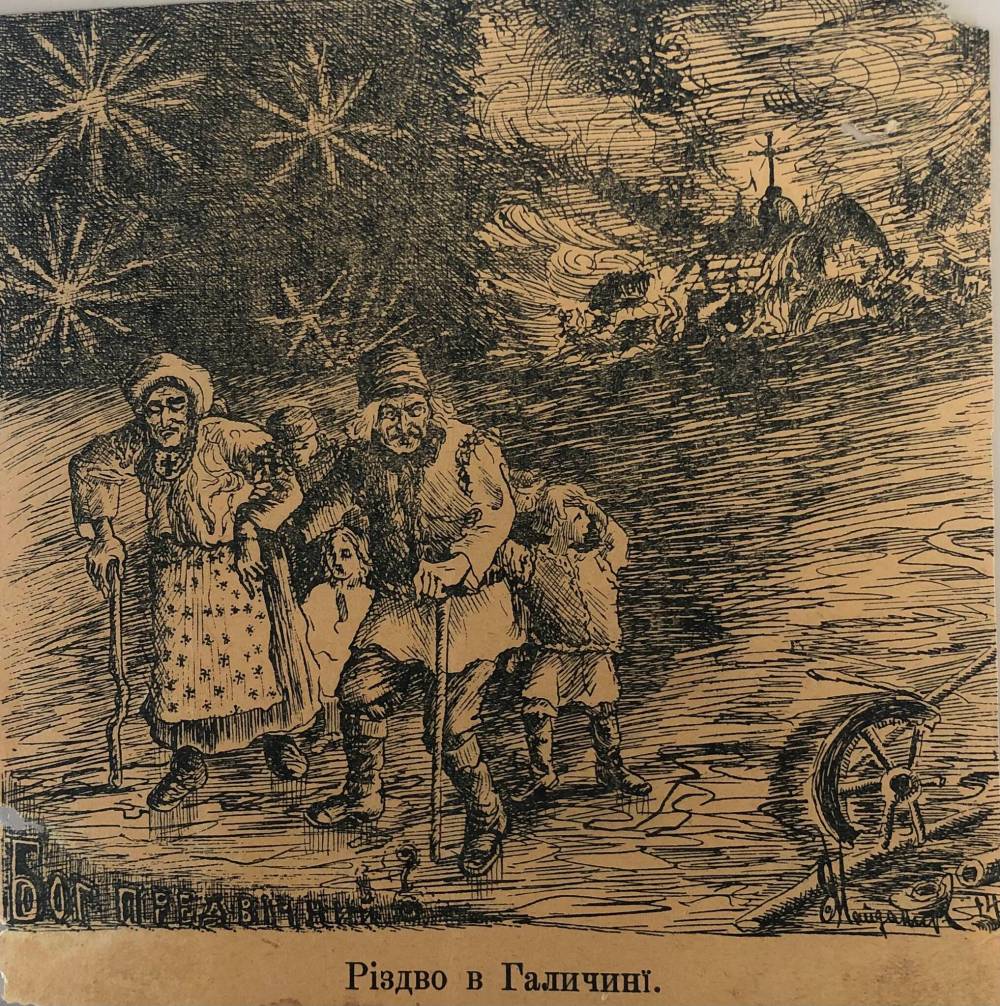

In one drawing, an ornate, pastoral Ukrainian church, with its characteristic domes and ornamentation, is surrounded by scowling wolves representing poverty, death, disease, and hunger. In another, a poor, skin-and-bones peasant is greeted not by Christmas carolers, but skeletons, wolves and enemy forces singing songs of conquest, with a church burning in the background. In these illustrations, Maydanyk’s skill — flattened and simplified in his comics to produce comedy — is cast in a different light. His training as an iconographer, and his fine art aspirations, come through, showing his mastery of metaphor, scale and storytelling.

Sometimes, he did it without words, as was the case in a mid-war sketch of a grandmother carrying a bundle of sticks on her back through an evil forest, with her granddaughter clutching the elderly woman’s hands in horror as the trees spring to life, appearing to signal to the duo that they are not welcome on their own land. Perhaps, the land was never truly theirs to begin with. A crow circles above, and Maydanyk uses white paste, perhaps to represent lightning in the distance — a bleak storm on the horizon.

Olesia Sloboda looks at these drawings a few weeks after the current Russian invasion of Ukraine began, a conflict which has enraged and captivated the world. For Ukrainians and Ukrainian-born Manitobans like Sloboda, the war has been a painful reminder of a history of occupation and violence against Ukrainian sovereignty. “These images are sadly very relevant today,” Sloboda says. They could have been drawn and published for the first time yesterday.

More than a century earlier, though thousands of kilometres away from his homeland, Maydanyk was not a stranger to the conflict of his lifetime: he maintained contact with family members who remained in Ukraine, and even had an early love there with whom he had wanted to reunite on a day which would never come. Meanwhile in Manitoba, the First World War fuelled already rampant discrimination against Ukrainians, mostly from the provinces of Galicia and Bukovyna, which were technically under Austro-Hungarian rule. According to the Manitoba Museum, of 8,579 people interned in Manitoba as “enemy aliens” under the War Measures Act once the country went to war with Austro-Hungary, nearly 6,000 were Ukrainian.

Maydanyk’s artwork, in all its forms — comic strip, cartoons, and religious iconography — became even more inherently political. They communicated to the common man the struggle of a people forced into constant assimilation. Even simple Shteef Tabachniuk understood he was treated as a second-class citizen, no matter where he went.

—

By the time Halya Kuchmij met him, Jacob Maydanyk was an old man.

In her 20s, she was an aspiring and budding filmmaker from Toronto who had recently graduated from York University with an eye toward feature films; she soon would become the first Canadian woman to graduate from the American Film Institute. But the documentary form called to her, and in Maydanyk, she saw a person worth exploring through her lens.

“I was very impressed by Jacob. His whole character. His style, his intelligence, his awareness, his talent,” said Kuchmij, nearly 45 years after she met him. He was a remnant of a distant era, still wily and with it. “His whole manner and being suggested a time before, a time I had never been a part of. A time when manners were important. He was elegant, and he was sophisticated.”

Kuchmij pitched the documentary to the National Film Board’s Roman Kroitor, a Ukrainian Canadian filmmaker from Yorkton, Sask., who was one of the leading voices of the NFB; Kroitor worked on documentaries about Paul Anka, Stravinsky, Glenn Gould and Paul Tomkowicz, a Winnipeg street railway switchman; he also is credited as a co-creator of Imax. Kroitor gave Kuchmij the greenlight, assigning Wolf Koenig as producer and editor.

She met Maydanyk at the Providence Church Goods shop at 710 Main St., a building which no longer exists, and by 1977 was not a brisk operation: most churches had all the icons they needed, so the 86-year-old Maydanyk, soon to retire officially, had already unofficially done so.

His short stay lengthened. He got married to a woman, Katherine, and had three children. He lived in a modest house in Elmwood, bought land in Selkirk, where he went fishing in the river, and had his own personal apiary, where he kept bees and made honey. He wore a three-piece suit every day. He snapped his smokes in half and removed the filters, smoking them through a cigarette holder. He put his own honey in his coffee. At the end of the day, he drank a shot of brandy. He was better than Tabachniuk, but by no means perfect. Like his famous creation, Maydanyk was still a man of the people.

Maydanyk gave Kuchmij the keys to the store, and in 1978, she spent many days there interviewing the artist, who was like the grandfather she never met. “By the time I met him, he was kind of an unknown. Known in his community, maybe, but to most just another old man telling stories,” Kuchmij said. Meanwhile, Shteef Tabachniuk had also become a bit of a relic.

Above the shop, Maydanyk kept a studio, filled with oil paintings and a variety of art that showcased his virtuosic talents. Folklorist Robert Klymasz recalls seeing paintings of fawns and portraits up there, not just cartoons. On his wall, he had a list of friends’ names; about two-thirds were crossed out as Maydanyk neared 90. In Kuchmij’s film, she captures Maydanyk stroking his brush across a canvas to paint Jesus Christ as a worker on the extra gang, carrying a cross made out of railroad track.

“Some call him nationalist. Some call him socialist,” narrator John Colicos says in the film. “Some say he’s Catholic. Others say he’s Orthodox. Some even say he’s an atheist. Most people thought he died a long time ago.”

Throughout her film, Kuchmij explored Maydanyk’s life and the life of Shteef Tabachniuk as they paralleled the Ukrainian Manitoban experience. She traced the arrival of the first waves of immigrants, the arrival of Maydanyk, the creation of Tabachniuk, and their apex of renown. She wanted to do a biography of not just Maydanyk, but a time gone by.

They became good friends: he took Kuchmij to his apiary, where he let the bees sting him because he believed it would give him boosted immunity. “I did the same, and luckily I wasn’t allergic,” she said. The more time she spent with the artist, the more Kuchmij was convinced she was in the presence of a brilliant man. “He was a genius. A forgotten genius.” The film — along with his iconography at a dozen Manitoba churches, including Winnipeg’s Holy Ghost Ukrainian Catholic Church — stands as one of the few tangible ways for the public to remember him.

Laughter in My Soul premièred at the Winnipeg Art Gallery in 1983, and Maydanyk, by then 91 years old, attended in his customary three-piece suit. “He seemed a little overwhelmed by all the attention, but handled it beautifully,” said Kuchmij.

The film portrayed the artist as a man who was once ahead of his time and by then was behind. It was sympathetic and nostalgic, and it was honest. “There was a time when everyone knew the name of Shteef Tabachniuk. He was a great hero to his people. Today, not many remember, and Maydanyk is just another old man,” the narrator said in a final scene, at a Ukrainian parish hall celebration, where Maydanyk sits in a chair, smiling as the young people dance.

“Well, a baba (woman) made this film,” Maydanyk told Kuchmij after the final credits, which rolled one year before his life ended at the age of 93. “But it is very good!”

Paris it was not, but he had left his mark, in ink, paint and pencil. Everyone took a shot of brandy, and the artist smiled as he raised his glass.

ben.waldman@winnipegfreepress.com

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.