Wordle not enough of challenge? How’s your Low German? Enthusiastic Mennonites flock to Manitoban’s ‘really terrible idea’

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 23/03/2022 (1358 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Name a five-letter word for things you put in the ground to grow plants. No, not “seeds,” but you’re close, kind of.

It’s “zoats.” Or is that “zoate?”

If you’re going to take on the latest spinoff of the New York Times Wordle puzzle craze, it’d be a good idea to have a friend who speaks Low German nearby.

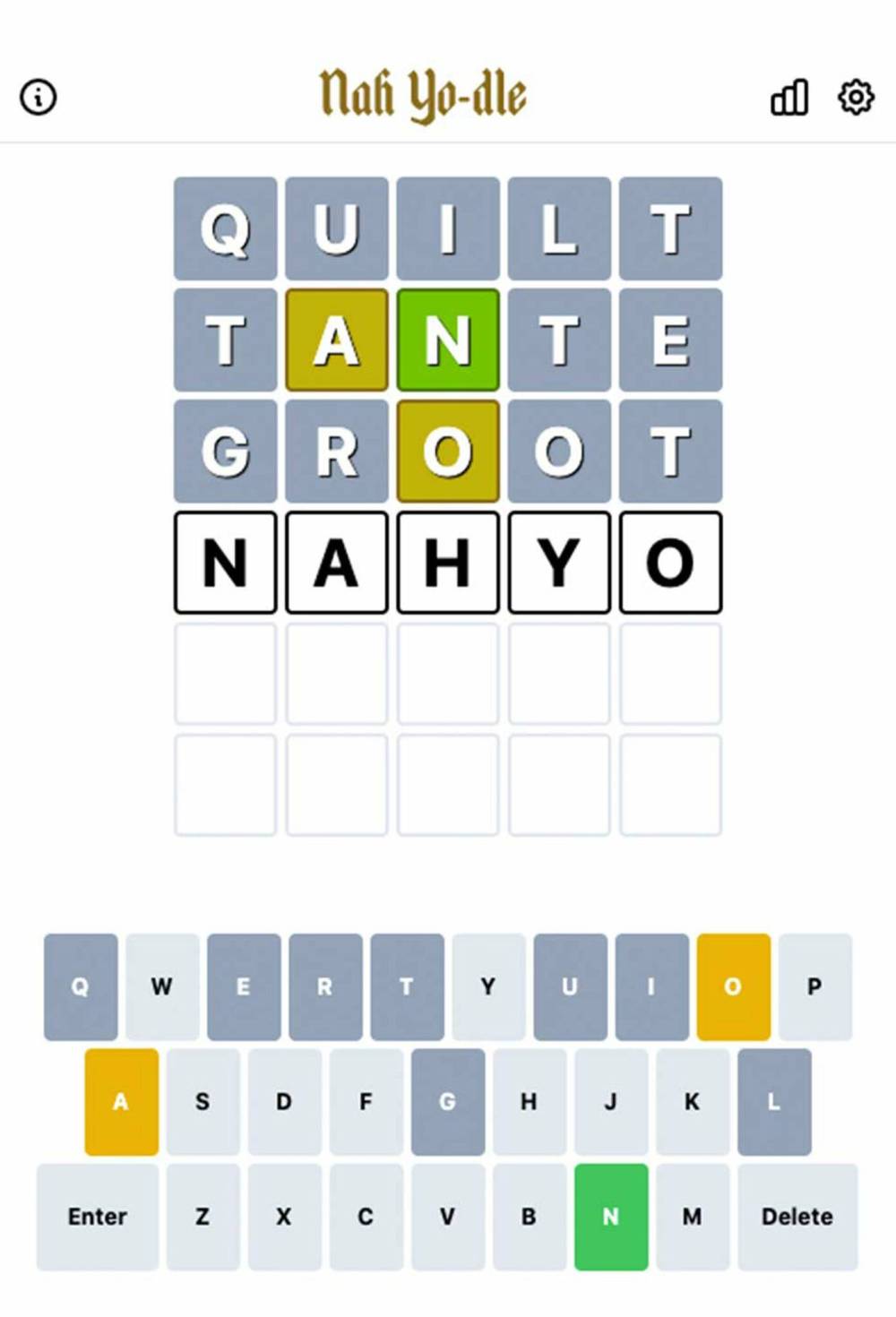

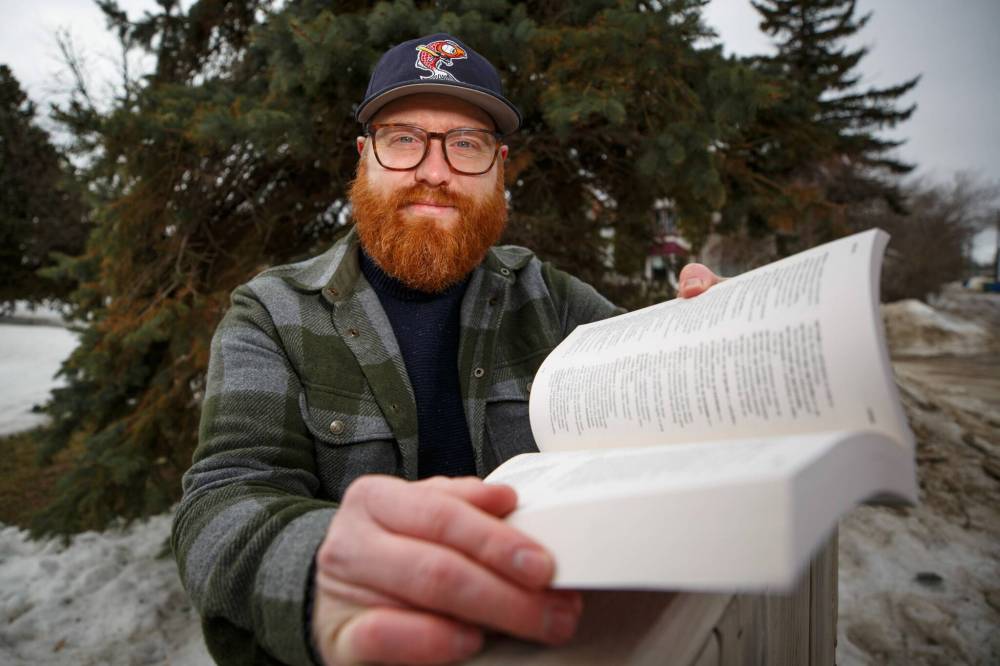

Altona-born Jared Falk has created Nah Yo-dle, a Wordle clone in which players guess a word of the day in the language of Manitoba’s Mennonite culture.

“You know when you have a really terrible idea and you think that’s not going to work, but then you actually do it? That’s really where this all came from,” Falk told the Free Press.

As several variations on the original game emerged, Falk saw an opportunity to pay homage to his Mennonite heritage. He called up a friend, Adrian Trimble, with the back-end skills to make it happen, and the two got to work.

After taking a bit of open-source code and building up a library of more than 1,000 Low German words, Nah Yo-dle was born.

Nah yo is a common Low German phrase meaning something like “well then,” and it became the game’s title after a gruelling selection process.

“I told my friend we’re going to make this Low German Wordle game. He said, ‘Oh, that’s great. What’re you going to call it?’ And that was the first thing that popped into my head,” Falk said with a chuckle.

The off-the-cuff, somewhat silly naming is, itself, something of a salute to Mennonite culture, he said.

“There’s a weird thing that’s embedded into Mennonite culture where we like to make fun of ourselves,” he said. “There’s lots of puns and a lot of satire that’s built into the culture. That’s one of the main methods of conversation and communication.”

But Falk’s online game has not been without controversy. Low German’s relatively recent arrival on the written-language stage has left it without much standardization in spelling. Combine that with a population of speakers increasingly influenced by surrounding anglophone communities, and you’ve got yourself the ideal conditions for toe-to-toe battles among amateur grammarians.

Take Nah Yo-dle’s very first word, for example: “zoat,” meaning seed, singular (maybe). Do you end with an “S” to make it plural, as English words do? There’s a lot of English bits and bobs that have trickled into the language, after all. Or do you end with “E” to make it plural, as German words do? Or is zoat a collective noun?

“I can’t find any proof one way or another whether there’s a plural beyond z-o-a-t,” he said, a touch of friendly exasperation in his voice.

Whatever the case, people have been flocking to Falk’s game. In the first three days, about 2,000 people from Manitoba, Saskatchewan, British Columbia, Ontario and the eastern United States have tried their hand at it, he said.

Winnipegger Geoff Reimer is one of them.

“I think it’s amazing,” he said. “Being a Mennonite myself, you don’t see a lot of Mennonite things.”

Reimer said he’d wanted to get people together to learn some Low German words and share some food, but he’d never quite got around to it. So when he saw Falk’s game, he was ecstatic, not only to play the game, but also to connect with some members of the Mennonite community.

“When I checked the 17 followers it had at the time, I thought, ‘These are the people I want to invite to my little picnic table,’” he said.

For Falk, too, it’s a way to connect the language his parents used to speak when they didn’t want him to understand, which may have been a crafty and effective way to get him interested.

“I wasn’t supposed to know; so of course, I’m going to try and learn,” he said.

And it’s a way to honour his heritage and to poke some fun at it which, he figures, might just be the same thing.

cody.sellar@freepress.mb.ca