The art of representation Black faces on stage and behind works exhibited at Winnipeg’s four main culture centres have been few and far between

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 18/03/2022 (1361 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Jauvon Gilliam was born and raised as an only child in Gary, a rust-belt Indiana city home to a predominately African-American working class. Located roughly 50 kilometres southeast of Chicago on the edge of Lake Michigan, Gary was once known as the “magic city,” anchored by the largest steel plant in America.

By Gilliam’s childhood in the 1980s, Gary had begun its decline along with America’s steel industry. Economic struggle led to poverty, and poverty led to violence.

“My dad used music to keep me away from the guns and the drugs,” Gilliam, 42, says over the phone from Washington, D.C. “Gary was, at that point in time, very rough and tough, and so he used music to keep me safe.”

Music didn’t just keep him safe. It became his life. And, in 2002, at the age of 21, he won an audition: that of principal timpanist in a symphony orchestra.

Orchestra positions are few and far between, especially first chairs and especially for timpanists. “It’s easier to get into the NFL, statistically,” Gilliam says. So you go where the gig is. And this gig happened to be in Winnipeg.

But it wasn’t just a dream job for Gilliam. It was also a history-making one. He became the first Black principal player in the Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra. He’d make history again, seven years later, when he became the first Black principal player in the National Symphony Orchestra in D.C., where he’s going on his 11th full season.

D.C. is where Gilliam was living in May 2020 when George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, was murdered by Minneapolis police, igniting hard conversations about racism, oppression and white supremacy. That summer, Black Lives Matter protests swelled beyond America’s borders, spilling out into a global movement.

Arts institutions — particularly those rooted in Eurocentric, colonial art forms that skew white and male — were also sites of racial reckoning, and began the uncomfortable, necessary work of interrogating themselves and the power structures that have upheld them for generations. Who do we see onstage — and not? Who gets promoted in a ballet company or in an orchestra — and not? Whose stories are being told — and not? Whose work is absent from major art exhibitions and playbills? And crucially: how can arts institutions meaningfully address systemic racism, and how can they do better?

“Representation matters,” Gilliam says. “People who look like you who do the same thing matters. And (representation) might be a little bit buzzy these days, but the only reason that it’s buzzy is because of these very gruesome, nonsensical killings that are happening down here. And while it might be something of a buzzword as of late, it’s far, far overdue.”

Winnipeg’s arts institutions — some more than a century old or approaching that, some with the “royal” designation in their names — were not exempt from the work of moving forward.

Here, we look at the Black histories — the firsts and the trailblazers — but also the Black futures of four of Winnipeg’s major arts institutions: the WSO, the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, the Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre and the Winnipeg Art Gallery.

● ● ●

Legacy arts institutions have long had to grapple with the question of relevancy and longevity. A storied past doesn’t guarantee a glittering future, especially if one does things the way they’ve always been done.

For WSO’s executive director Angela Birdsell, diversity is a matter of the organization’s survival.

“I truly believe that for the orchestra to survive into the 21st century, we’re going to have to continue on this path,” Birdsell says. “And we’re going to have to absolutely increase our efforts in not only having diverse artists and diverse composers, but ensuring that we start really becoming very aware of our community and who we’re seeing in the hall, and how we reach different neighbourhoods and different community groups so that people feel welcome in the hall.”

The music heard in the hall is a particular focus as of late: it’s not all Bach and Beethoven. The 2021-22 season, for example, featured works by living Black composers, including Omar Thomas’s Of Our New Day Begun — a commission to commemorate the 2015 Charleston, S.C. shootings in which nine Black churchgoers were murdered — and Jessie Montgomery’s Records from a Vanishing City.

These are composers, Birdsell says, who see symphonic music as a “living, evolving, shifting art form. Yes, we do play the classics. And many of those classics have their origins in the European tradition. But honestly, there are artists in the classical music world from every single country of the world who are making their mark in this art form.”

And these composers are in demand. According to a recent New York Times profile on Montgomery, the number of times her orchestral works have been programmed has more than doubled each year from 2017 to 2020.

But the 39-year-old dynamo from New York City also expressed the pressure and burden that can come with representation, especially if done in a tokenizing way in which her work feels secondary to her skin colour. “I’ve been talking with my colleagues of Black descent, and we’re all feeling that sort of thing of being put on,” Montgomery told the New York Times. “I’ve been realizing that there’s this shared desire to just be able to create without that kind of pressure or expectation that you’re going to be the spokesperson for the race or for classical music being better or more diverse or whatever.”

The WSO has also featured Black guest artists in its history — including the late groundbreaking conductor James DePreist, one of the first African American conductors to achieve world-wide acclaim, who appeared as a guest conductor with the WSO in February 1980.

But representation also must extend to who works within the ranks of the organization and who is seated in the orchestra, too. Gilliam was one of two Black principal musicians at the WSO during his time there; Toronto tuba player Chris Lee joined the WSO in 2003, a year after Gilliam, and was there for 15 seasons.

Changing the makeup of an orchestra involves working from two directions, Gilliam says. “I think there’s a systemic issue, which is working from the top down. And then there’s also the grassroots issue, which is working from the bottom up, I think it’s going to take both of those perspectives to make it work.”

Gilliam points to the Rooney Rule in the NFL — which requires league teams to interview candidates of colour for head coaching and other senior roles — as one example of a way an orchestra could change the landscape of not just who is onstage, but who is working in the executive level and on the board as well.

“I think that’s a very tangible, clear way that they can do things to allow for this diversity to come a little bit more naturally,” Gilliam says. “Change is hard no matter what. And so, being open to that change, and being able to listen to people like myself who have created this sort of template that will help foster the change, I think is what’s important.”

“Change is hard no matter what. And so, being open to that change, and being able to listen to people like myself who have created this sort of template that will help foster the change, I think is what’s important.” – Principal timpanist Jauvon Gilliam

Like many orchestras, the WSO uses a blind audition process, with candidates auditioning from all over the world. But blind auditions can’t alone ensure diverse orchestras if there’s not a diverse set of candidates auditioning. This is an example of working from the bottom up: providing early opportunities so kids and young adults can get the kind of training required to get to the level where they could audition and win a chair in an orchestra. If the number of Black students that make up the population at music schools is disproportionately small, addressing the issue at the audition stage is too late.

Birdsell highlights the Sphinx Organization in the United States, a non-profit aimed at the development of young Black and Latinx classical musicians, as an example of an organization doing this kind of work. So, too, is WSO’s Sistema program. Inspired by the El Sistema movement that began in Venezuela in 1975, WSO’s program has been running since 2011 and delivers musical training to children in Winnipeg’s North End every day after school at no cost to their families. Birdsell says that about 50 to 60 per cent of the kids in the program are from diverse family backgrounds, and 30 to 40 per cent are Indigenous.

Gilliam says that kind of exposure counts for a lot.

“For classical music — and I’m sure it’s like this for ballet, as well — it’s, on some level, simply showing this child that this is an option, introducing them to the actual idiom,” he says. “And isn’t even really about getting them to learn how to listen to Beethoven or listen to Brahms or to dance to Tchaikovsky, it’s literally letting them see that there is this thing out there called a symphony orchestra that you can do. It really starts at that low, sort of grassroots level.”

Gilliam knows first-hand the power of representation. It changed the trajectory of his career.

He started in piano lessons back in Gary. His talent and work ethic took him all the way to Butler University in Indianapolis on a piano scholarship.

But he switched to percussion in his sophomore year after seeing Timothy Adams Jr., the former principal timpanist in the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. Adams Jr., who is Black, had instructed Gilliam’s teacher at Butler, and made an immediate impression on a young Gilliam.

“When I saw him in his three-piece suit, and his fancy car, and his very well put-together outfit, I was like: ‘that is exactly who I wanna be like,’” says Gilliam, who met Adams Jr. at a conference. “I made a beeline for him and I said, ‘Hey, I want to do what you’re doing.’ And he basically took me under his wing. Seeing someone who looked like me, being able to do this, is what set me on my path.”

“I made a beeline for him (Timothy Adams Jr.) and I said, ‘Hey, I want to do what you’re doing.’ And he basically took me under his wing. Seeing someone who looked like me, being able to do this, is what set me on my path.” – Jauvon Gilliam

For his part, Gilliam loved his time in Winnipeg, finding the orchestra and community collegial and friendly. “I call myself a de facto Canadian, because my seven years in Winnipeg were some of the best years I’ve ever had.” And, like his mentor, he became an educator, having taught percussion at the University of Manitoba and currently at the University of Maryland.

The idea that he could be an Adams Jr.-like role model for other young Black musicians is something he relishes.

“It’s really important to me ‘to’ be that,” he says. “That’s something I take very, very seriously and don’t take for granted. Being the first and only Black principal in both bands — in the Winnipeg Symphony, obviously, and also in the National Symphony here, I’m the first and only Black principal — that’s something that I don’t necessarily feel is a weight. I feel like it’s actually a platform, where I can lead by example, and show up to work, do my job with excellence, and then try to, in my teaching and other things that I do, make sure that I am positioning myself to be seen by some of these young inner-city, young under-underrepresented, young under-served communities, so that they can have an opportunity to know that this is an option for them.”

● ● ●

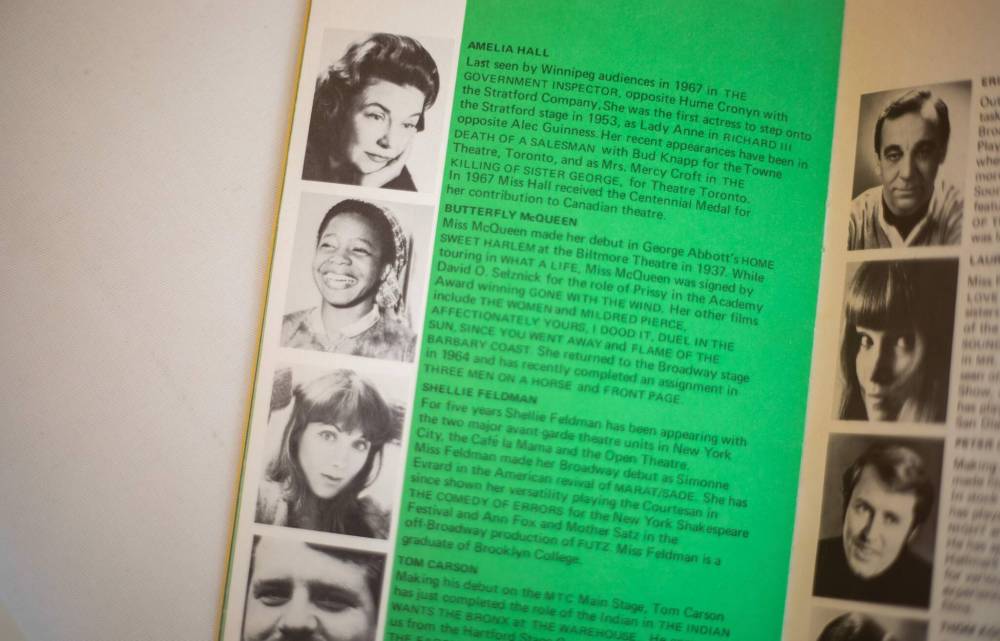

A 1970 production of Gregory S. Kaufman and Moss Hart’s comedy You Can’t Take It With You is likely the first time Black actors appeared in major roles in a Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre production.Their performances are sidelined to a single line in the Free Press review from March 10, 1970: “William Jewell and Butterfly McQueen also worked well together as jolly Negro domestic servants.”

McQueen was frequently typecast as a maid after she played a famous one: she starred as Prissy in 1939’s Gone With The Wind, the premiere of which she wasn’t allowed to attend because it was held in a whites-only theatre. “I didn’t mind playing a maid the first time, because I thought that was how you got into the business,” she once said. “But after I did the same thing over and over, I resented it. I didn’t mind being funny but I didn’t like being stupid.”

More than a half-century later, the stories being told on RMTC’s stage have changed — and they include the kind of multi-dimensional roles McQueen craved.

Audrey Dwyer is the associate artistic director of RMTC, and she’s also a director, actor and playwright. She wrote Calpurnia, which opens March 23 on the John Hirsch Mainstage.

A comedy that explores the intersections of race, class and gender, Calpurnia was inspired by Harper Lee’s 1960 novel To Kill A Mockingbird, which Dwyer, a born and raised-Winnipegger, read as a high school student at Sisler. The play centres on Julie, a Canadian-Jamaican playwright who is working on an adaptation that examines the novel’s treatment of Calpurnia, the Finch family’s maid. Julie’s brother takes issue with his sister’s project, and things come to head at the family dinner table, over a meal prepared by the family’s Filipina housekeeper, Precy.

“I wanted to examine that book through a modern lens,” Dwyer says via Zoom. “I also wanted to write something that dealt with a young woman growing into her politics. You’re not born with your politics. They are things that you learned through experience, and obviously reading and research and all that. But I wanted to paint a picture of a family that’s rooted in love, and class, and to show how that family really bumped up against their own political ideas.”

Calpurnia was produced in Toronto in 2018 by Nightwood Theatre. “Things have changed a great deal since 2018 to 2022,” Dwyer says. “The whole world has changed.

“There’s been far more intentional educational opportunities — like, now more than ever. Between literature, television, film, you know, institutions making diversity training mandatory, there is a lot more education now than in 2018. So I had to make a number of changes to reflect that.”

Theatre, Dwyer says, is a powerful site for these kinds of conversations and stories.

“When you’re watching something live amongst people that you don’t know, there’s a vibrancy and an unpredictable factor,” she says. “And it can’t be replaced by film or television because literally anything can happen. I think one of the powerful things about being in an audience is, you know, laughter is infectious and you can feel the responses of the folks around you in real time. And it also tells you about your community. Like, the way that audiences are reacting around you is information about the world around you, in the present. And that’s what makes theatre so exciting for me.”

“I want to acknowledge that artists and activists and audiences and theatre leaders have been working towards diverse practices and diverse stories for many years, and so what may feel new is actually very old.” – Audrey Dwyer

Dwyer says that representation and the act of theatre, of having stories reflected back to an audience from the stage, has always been transformative. As such, she says the work to make theatre more diverse and inclusive has been going on for a long time.

“I want to acknowledge that artists and activists and audiences and theatre leaders have been working towards diverse practices and diverse stories for many years, and so what may feel new is actually very old,” she says. “And so the work that we’re seeing today is very much due to so many artists who have come before or asking for different stories — and audiences, too, that have been asking for different stories. It’s really important for me to acknowledge and really give thanks to all of those people who have been doing that long, tiresome, emotional work.

“I will say that since the murder of George Floyd, the issues of Blackness and Black survival, have taken a greater impact that we’re now in an age where we are asked to be more accountable than ever,” she continues. “And people are asking us, as a people, to be thorough, to listen and to be sensitive to people’s stories and what they need. And so it’s a very interesting time, because we’re learning about it in our workplaces and we’re also learning about it on our stages, and we’re learning about it in all different mediums from literature to film to commercials. It’s really around us now. Folks are really listening and finding unique ways to address representation.”

“As Canada’s oldest English-speaking regional theatre, we acknowledge that MTC has benefited from colonial structures and the systemic racism that exists in our society.” – RMTC Commitment to Action pledge

In July 2020, RMTC posted its Commitment to Action to its website. “As Canada’s oldest English-speaking regional theatre, we acknowledge that MTC has benefited from colonial structures and the systemic racism that exists in our society,” the statement, which was signed by executive director Camilla Holland and artistic director Kelly Thornton, reads in part. Regular updates and progress reports have been posted as well. Holland says the commitment to action, which includes equity, unconscious bias, anti-oppression and anti-racism training, among other items, has been a “guiding map” for the organization.

And some of the points on that map will soon be visible to audience members: the just-announced 2022-23 season features Rosanna Deerchild’s The Secret to Good Tea, which was developed through the Pimootayowin Creators Circle — which is now in its second year and was one of the initiatives outlined in the commitment to action. The season also includes Trouble in Mind, by celebrated Black novelist, playwright and actor Alice Childress.

“We do have a lot of plans upcoming,” Dwyer says. “And we have these conversations regularly and consistently with our artistic staff and the teams here. I’m really happy to be working in an organization that wants to create change.”

● ● ●

It’s a Thursday afternoon in February, and Tony Williams has just finished teaching dance class at the Tony Williams Dance Center in Boston.

At 75, Williams has long been retired as a ballet dancer, but he has no plans to retire as the founder and artistic director of the dance centre that bears his name, located in Jamaica Plain, the Boston neighbourhood he grew up in.

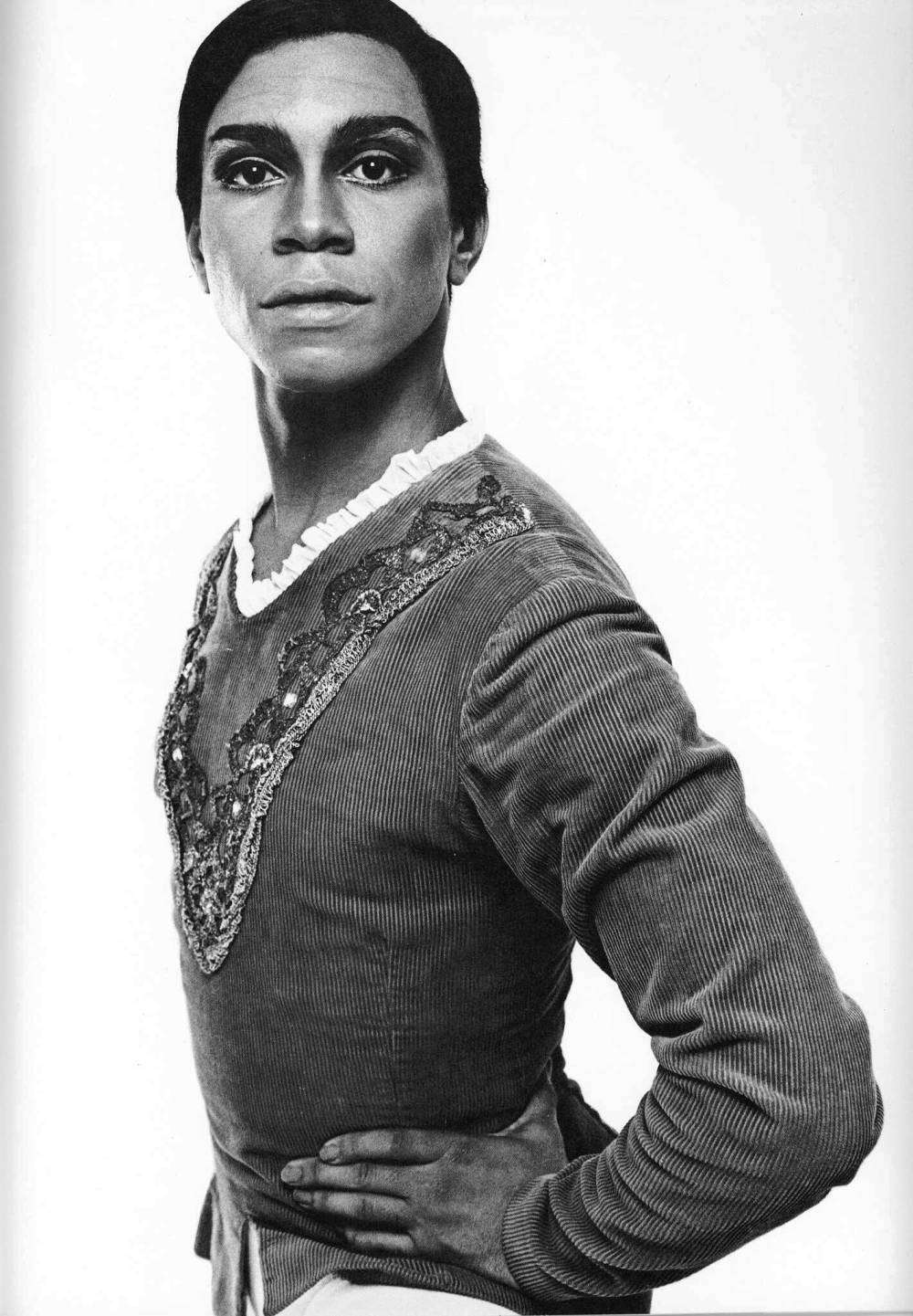

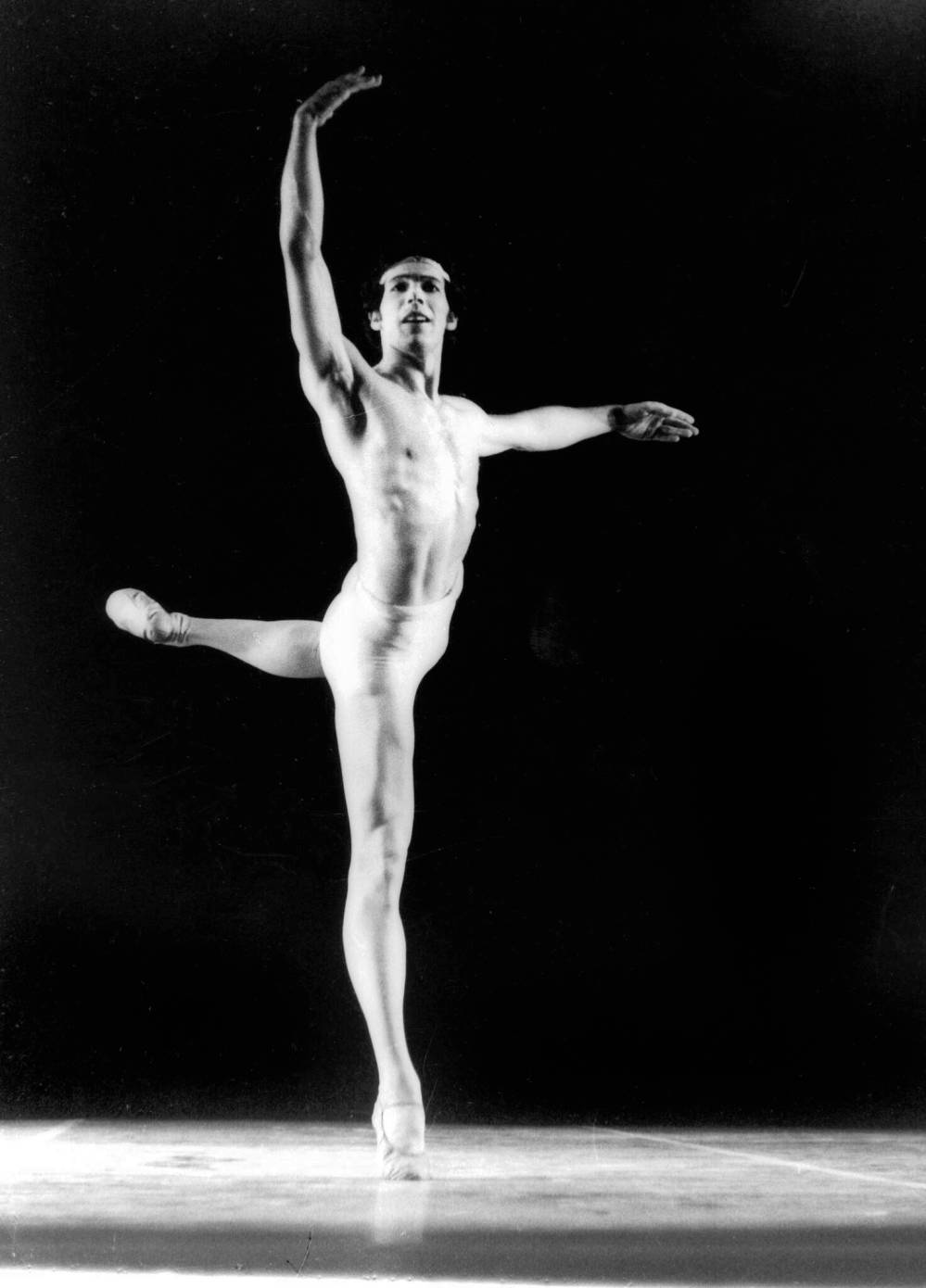

Williams’ ballet career hasn’t always kept him so close to home. From 1973 to 1976, Williams was a principal dancer in the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, one of the few Black dancers to reach the highest rank within the company, along with the late Sylvester Campbell, who was a principal dancer at the RWB from 1972 to 1975. Currently, there are no Black dancers in the company.

Other trailblazers at Canada’s oldest ballet company include James Thurston, who was a soloist (a rank below principal in ballet hierarchy) with the company from 1967-1969, and original Dreamgirls co-choreographer Michael Douglas Peters — also dubbed “the Balanchine of MTV” for his work on a host of iconic music videos, including Michael Jackson’s Thriller — who choreographed L.I.F.E. (Love Is For Eternity) for the Royal Winnipeg Ballet’s 50th anniversary gala in 1989.

Williams’ time at the RWB was short, but transformative.

“I think it was the best experience of my life as a performer, and that was because of Mr. (Arnold) Spohr, who was the artistic director at the time,” he says via Zoom from an armchair in his office in Boston. Evidence of a creative life surrounds him; every surface, it seems, is piled with books and souvenir programs. “He was a master artistic director; he really knew how to put together a repertoire that was appealing to an audience.”

Anthony Williams was born to an Italian mom and an African-American dad in Italy shortly after the end of the Second World War. His father, Edgar, was a GI and was one of the soldiers who helped save his mother, Addolorata, and her community from starvation. They arrived in the U.S. when Tony was 10 months old, settling down in Jamaica Plain.

Williams didn’t think about his race a lot as a child growing up in Massachusetts. Or rather, no one really talked about it.

“It was pretty much 100 per cent Caucasian, like no brown, no Black. It was all white except for me. And I was very talented, so I was accepted.” – Tony Williams

“I’m biracial and also multicultural,” he says. “I could sort of pass for, ‘What are you, Cuban? Or Spanish or Indian?’ It was like, oh, gee, I can sort of float between two cultures. And as a kid, you don’t think about it. People would say, ‘Oh, you’re coloured, right?’ Or they would say, ‘What are you?’ So if ‘they’ didn’t know what I was, as a young kid without any counselling, or someone saying, ‘Tony, this is who you are, this is the world…’

“You know, now, Black folks will say to their Black sons, ‘if you’re in a car in this country, don’t be defensive. If you get stopped by a cop, you just put your hands on the steering wheel, so you don’t get shot.’ But back then it was like we were on our own.”

Williams didn’t discover ballet until he was a teenager, and took to it instantly — but he was also acutely aware that no one else looked like him. “It was pretty much 100 per cent Caucasian, like no brown, no Black,” he says. “It was all white except for me. And I was very talented, so I was accepted.”

Williams trained at the Boston School of Ballet, where he received a scholarship, and later danced in the Boston Ballet. At that time, a friend and fellow dancer encouraged him to try and pass as white. “He said, ‘Tony, you know, to get ahead, you really need to say that you’re white and you’re not Black; you need to pass for something else to get by in this white world.’”

But when Williams landed a job as a soloist at the prestigious Joffrey Ballet in New York City in 1967, his world expanded. “I was stunned because there were four Black guys in the company — no Black girls — and I was like, ‘Wow.’ I remember one of the guys who was light skinned and had kinky red hair and we became very close friends.”

That dancer’s name was Richard Browne. He took Williams under his wing, just as Timothy Adams Jr. would for Jauvon Gilliam decades later. “I came into myself and accepted who I was,” he says.

“And now with my work, working with kids, I’m always talking about diversity and I talk about my story, about inclusion. And it’s not just racially, it’s inclusion of everyone. We’re not all on the same spectrum. Everyone’s someplace, and we all need to accept each other.”

The Tony Williams Dance Center’s mission is to build diversity through dance. In addition to offering instruction, the centre is also the home of City Ballet of Boston and the beloved Urban Nutcracker, which just celebrated its 20th anniversary season. The TWDC’s ballet program is for all kids who want to become professional dancers, “but we have a real thrust outreach for Black and brown girls, in particular,” Williams says.

Through his career, Williams has noticed a dearth of Black ballerinas. In 2015, American ballet dancer Misty Copeland made history when she became the first African-American ballet dancer to be promoted to principal dancer in New York City’s American Ballet Theatre — but she was not the first African-American ballerina. Many Black ballerinas came up through Dance Theater of Harlem, the pioneering company founded by Arthur Mitchell, the first Black principal dancer at New York City Ballet, but their names have been relegated to the footnotes of ballet history.

As to why Black men have historically found more success in ballet, Williams says Black boys tend to have more opportunities because there are fewer boys in ballet, in general.

But there are also other insidious barriers for Black girls, including the esthetics of European ballet itself, which are rooted in white supremacy. Ballerinas are synonymous with a very specific body type: that of a small, thin, white woman — right down to pale-pink satin pointe shoes meant to elongate her leg. Hence the practise of “pancaking”: dancers of colour having to cover their toe shoes with makeup.

If, at the student level, girls are self-selecting out of ballet because they don’t fit that narrow aesthetic and never see themselves reflected onstage as, say, The Nutcracker’s Clara or Swan Lake’s Odette/Odile, or because they are discouraged from continuing to pursue the form, the result is the same: unrealized talent, crushed dreams, and less-diverse ballet companies.

Tara Birtwhistle, the associate artistic director of the Royal Winnipeg Ballet, says the ballet world is talking about systemic racism in a way it hasn’t before.

“Everyone was aware, but we were never comfortable enough to actually have the conversations,” she says via Zoom. “So I can certainly say that that is happening worldwide now.”

The RWB has joined the newly launched Cultural Competency and Equity Coalition (C2EC), a membership-based organization that will see peers work collaboratively to become anti-racist. The RWB is one of two Canadian ballet companies in the coalition, along with the National Ballet of Canada in Toronto.

C2EC was created by Theresa Ruth Howard, a former ballet dancer, the founder/curator of the digital archive Memoirs of Blacks in Ballet (MOBBallet) — which preserves and presents Black ballet history — and a prominent advocate for racial equity in ballet. As a speaker and writer, she’s addressed systemic racism and colourism — specifically how prejudice against people with darker skin means lighter-skinned Black dancers get more opportunities — in ballet. Now, in her work as a diversity strategist, Howard is helping dance companies reimagine what ballet can be.

”One of the things that Theresa asks us is, who decides what ballet is? Well, the leaders can decide what ballet is. We’re in our questioning period, really digging deep in ourselves and figuring out what the future looks like.” – RWB associate artistic director Tara Birtwhistle

“(Howard) has called the ballet world out, and has been calling it out for a very long time,” Birtwhistle says. “She has developed a curriculum, but it’s a place where we learn and talk and discuss together as an organization and as the culture of ballet in itself.”

Birtwhistle is excited to begin this work with Howard. “I think that this is going to push us forward,” she says. As the associate artistic director of an 83-year-old company operating in a centuries-old form, Birtwhistle knows that change will not happen overnight. But she knows that a different future can be authored by ballet’s current leaders. (The RWB is also in a unique position in that it has a training school, so it has an opportunity to diversify its pipeline of talent from school to stage.)

“We just have to start changing our thought process,” she says. “And one of the things that Theresa asks us is, who decides what ballet is? Well, the leaders can decide what ballet is. We’re in our questioning period, really digging deep in ourselves and figuring out what the future looks like.”

And that kind of digging is not comfortable, Birtwhistle acknowledges.

“It has to be uncomfortable,” she says. “Or we’ll never move forward. It’s OK to be uncomfortable. There’s been marginalized communities that have gone through this for generations.”

● ● ●

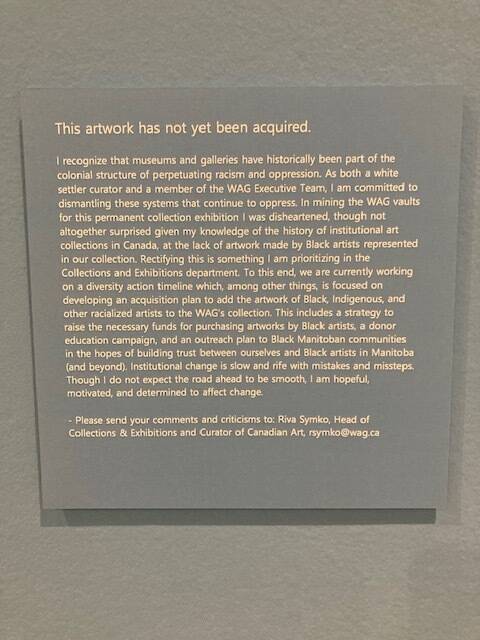

“This artwork has not yet been acquired.”

So read an unconventional museum label found in the Winnipeg Art Gallery’s In Place: Reflections From Manitoba exhibition, which was on view from October 2020 to May 2021.

“In mining the WAG vaults for this permanent collection exhibition I was disheartened, though not altogether surprised given my knowledge of institutional art collections in Canada, at the lack of artwork made by Black artists represented in our collection,” continues the statement, in part, from Riva Symko, head of collections and exhibitions. “Rectifying this is something I am prioritizing in the Collections and Exhibitions department.”

While the WAG has emerged as a leader when it comes to reconciliation and the Indigenization of a colonial art gallery — which includes the opening of Qaumajuq, a permanent home for the largest collection of contemporary Inuit art in the world — there’s still lots of work to be done when it comes to the representation of Black artists.

Stephen Borys, director and CEO of the WAG, says the organization’s previous — and continued — efforts on gender equity as well as the Indigenization and decolonization of the WAG have laid the groundwork to focus on this work.

“I would say 2020, even 2019, were critical years in terms of attention at the WAG, attention that allowed us to maybe go a little deeper to do some self-assessments. I would say the Black Lives Matter movement really launched one of the most important exhibitions we’ve ever done, Born in Power, which was curated by Jaimie Isaac, which opened the floodgates.”

Born in Power, which was on view from November 2020 to August 2021, was the first major exhibition at the WAG to really centre Black artists. Examining Black and Indigenous representation in photography and film, Born in Power explored the reclamation of photography and image making — itself often a tool of exploitation, colonization and objectification.

But the conversations about the lack of works by Black artists at the WAG predated the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020. In 2019, a group of Black art students from the University of Manitoba staged a topless performance art piece/protest at the WAG, calling attention to this issue.

“I think back to 2019 when a number of students from U of M asked us, ‘Why? Why not? Why aren’t you doing more?’ And that conversation was really a catalyst, because it allowed us to actually respond in this way,” Borys says. “What does a museum do? it collects, it exhibits and it produces programs. When you have weaknesses in one of those areas, you can build it up in another. So when Jaimie Isaac organized Born in Power, it opened doors, and people that didn’t feel comfortable, didn’t feel respected or didn’t feel welcome at the WAG slowly made their way in.”

”When Jaimie Isaac organized Born in Power, it opened doors, and people that didn’t feel comfortable, didn’t feel respected or didn’t feel welcome at the WAG slowly made their way in.” – Director and CEO of the WAG Stephen Borys

This summer, the WAG will host To Play In the Face of Certain Defeat, a major exhibition by London, Ont.-born artist Esmaa Mohamoud. Mohamoud uses sculpture, photography, video and installation to examine racial marginalization through the lens of professional sport.

In her statement from the In Place exhibition, Symko outlined her plans to develop an acquisition plan, among other initiatives. In that vein, Borys wants to keep the lines of communication open.

“We have done some things very well, we’ve done some things poorly, we missed the boat on some things — but we are trying to do better, to do more, and to be more impactful,” he says. “And so, when people know what we’re trying to do, what we would like to do, it helps us. It helps us with supporters, with patrons, sponsors, government funding, but most importantly, it tells the public, ‘Listen, we want to be part of a solution, part of a system, part of a conversation.’”

● ● ●

Bella Watkins was one of those kids who knew exactly what she wanted to be when she grew up.

“I pretty much told my mom at the age of three that I wanted to do ballet and I’ve been in ballet classes ever since,” she says with a laugh.

She’s come a long way from the small rec centre where she first took lessons; the 14-year-old is now a Level 3 student in the Professional Division at the Royal Winnipeg Ballet School. She attended the RWB’s summer Dance Intensive in 2019, and has been training here since, moving to Winnipeg from B.C. with her mom.

Being a Black ballet student has been “difficult,” she says. “Whenever you walk into a room of people who aren’t your colour, it’s like, you’re holding yourself to a higher standard,” she says. “Like, you have to do more, work harder, be different.”

Dailia Martin echoes that sentiment. The 13-year-old Winnipegger is a member of the RWB’s Junior Intensive Training Program for ballet, and also dances in the Junior Jazz Dance Ensemble, Intermediate Hip Hop and Intermediate Musical Theatre Dance Ensemble.

“For me ballet is something that I love very deeply,” Martin says. “And growing up doing ballet, it was predominantly white, and you just seem like you’re just different, like no one else is the same colour as you.”

Both girls believe ballet is changing when it comes to diversity — albeit slowly. “Little by little,” Watkins says.

“It’s been amazing being here,” she says. “I feel like I’ve gotten a lot of quality training. And I haven’t felt that different lately.”

Watkins has designs on becoming a choreographer, and would like to complete the teacher training program someday, too.

Martin, meanwhile, would like to dance with the RWB when she’s older. She believes in the power of representation. “I feel like it’s really important,” she says. “It can also just tell you that you can do anything. Even if you don’t look the same as everyone else, there’s opportunities for everyone and it’s not just restricted to certain people.”

Students such as Martin and Watkins are the future of ballet. And right now, there are other Black kids who are dreaming big for themselves, who want to see themselves and their stories on stages and screens and in galleries. They want to see that it’s possible, that there’s a place for them.

Every arts institution profiled in this story acknowledged that there’s lots of work yet to do. This work has to be consistent and the commitment has to be long-term. That’s where change happens. It’s not one season, or one exhibition, or one playbill. It has to last.

jen.zoratti@winnipegfreepress.com

Twitter: @JenZoratti

Jen Zoratti is a Winnipeg Free Press columnist and author of the newsletter, NEXT, a weekly look towards a post-pandemic future.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.