Decades of work on HIV opens window into ongoing COVID fight

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 08/03/2022 (1371 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

When the COVID-19 pandemic began, infectious disease researchers everywhere switched their focus to combat its threat. Two years later, their knowledge has led to vaccines, treatments and a better understanding of the novel coronavirus that has impacted daily life.

Decades of work on HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) has given some Manitoba researchers a prime view of how the immune system responds to COVID-19, and a window into the lessons society can learn from the ongoing HIV pandemic.

One of the most important, says University of Manitoba virologist Xiao-Jian Yao, is prevention.

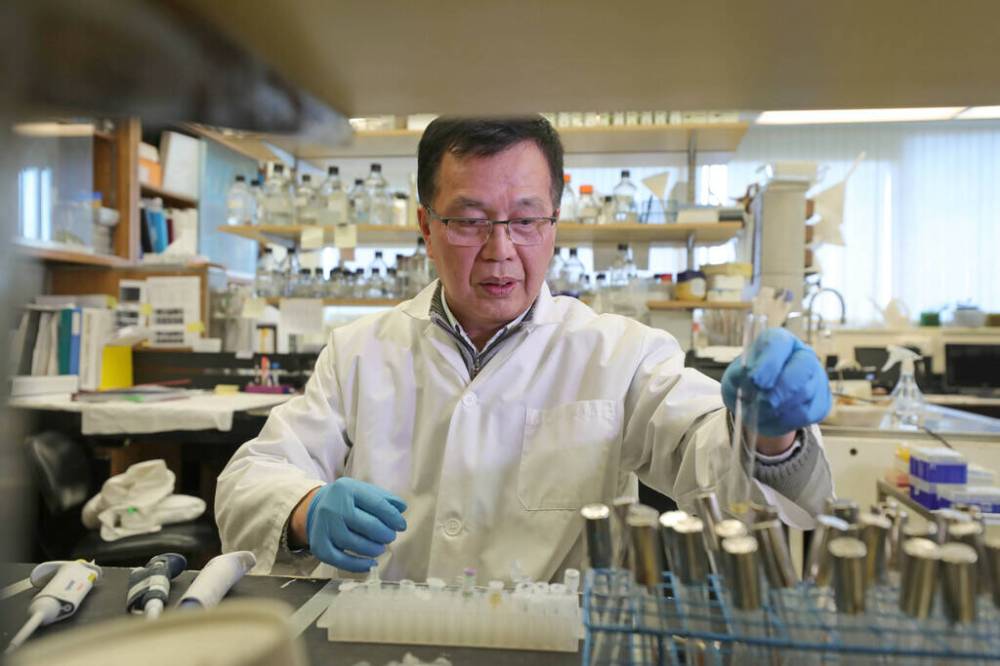

Yao conducted HIV research for more than 30 years before he adapted the vaccine technology he’d been working on for the fight against COVID-19.

He’s leading a team developing a dual COVID/influenza vaccine. Yao hopes it will become a tool to prevent COVID-19 infections while scientists develop new and better treatments for the respiratory illness.

“We are so busy,” Yao says. “In two years, I never rest.”

When asked what keeps him going, the director of the university’s molecular human retrovirology lab chuckles.

“I’m a scientist,” he says. “This is my life.”

As the novel coronavirus spread across the globe, respiratory research dollars poured in. Governments started investing in COVID studies, highly competitive grants cropped up, and scientists dropped what they were doing — or juggled cross-disciplinary projects — to find answers.

Since March 2020, Canadian researchers have received $250 million for 400 COVID-related research projects in federal funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Keith Fowke’s viral immunology lab at the U of M studies the immune system and how HIV interferes with it. Like so many researchers, his team had been asked to apply its HIV expertise to COVID-19.

“We are so busy. In two years, I never rest.” – U of M virologist Xiao-Jian Yao

“We’ve taken a lot of those tools and developed them to work with COVID. It took us probably five years to develop one test to study the antibodies that a person generates against HIV, but in a couple of weeks, we were able to develop that test to look at the antibodies that people develop to COVID or to the COVID vaccines,” Fowke said.

“So it has resulted in us quickly being able to apply our knowledge to our most recent threat.”

The viruses are extremely different.

HIV is bloodborne; COVID-19 is airborne. HIV mutates at a much higher rate. After one year of infection, someone with HIV carries more variants in their body than all flu variants in the world combined, Fowke says.

“The virus just mutates so quickly that we can’t develop a vaccine that can stay ahead of it, whereas with SARS-CoV-2, it mutates at a lower rate, and it’s going to be difficult to keep ahead of it, but I think we can.”

For all of the viral differences, HIV research has contributed a lot to scientific understanding of the immune system — and there are parallels between the two pandemics.

“Infectious diseases really bring out the inequalities of society.” – U of M associate professor Lyle McKinnon

Much of what they have in common is true for all pandemics: problems with widespread, global access to vaccines or treatments, stigma associated with infection, public fatigue and, often, lasting health effects.

Viruses prey on inequality, says Lyle McKinnon, U of M associate professor of medical microbiology and infectious diseases, who’s been studying HIV for 20 years.

“It’s the marginalized people in society who often have higher HIV burdens, and I think people in lower socioeconomic strata for COVID, it’s been very well established now, have higher COVID-19 risk, so I definitely think there’s some parallels there,” he says. “Infectious diseases really bring out the inequalities of society.”

McKinnon’s COVID-19 research looks up the nose: he’s studying the effects of COVID-19 vaccines on nasal cells.

Even as more people are vaccinated and protected against severe infection, transmission is still widespread, so there’s a need to figure out better immune protection where the virus enters the respiratory system, he says. As the science progresses, there may be more comparisons to draw between inflammation caused by HIV and inflammation caused by long COVID.

There’s a long way to go, but Fowke, U of M department head of medical microbiology and infectious diseases, says community involvement is key. People have to support the vaccines and treatments that are developed for them. Scientists have to understand how their work affects people and reach across disciplines to figure it out.

“In HIV, we’ve been doing that for now 30, 40 years,” Fowke says. “So I think that the wider scientific community is going to learn from our COVID experience on how to work more closely together.

“If we want people to accept getting a vaccine, then working with a wide range of people: policymakers and industry and community and scientists together… right from the beginning, is going to be really important.”

Outside the laboratory, the COVID-19 pandemic is not over yet. Another wave is likely — and Manitoba health officials are predicting a small one.

Deputy chief provincial public health officer Dr. Jazz Atwal says the province expects an increase in COVID-19 cases following the lifting of all restrictions.

“If we want people to accept getting a vaccine, then working with a wide range of people: policymakers and industry and community and scientists together… right from the beginning, is going to be really important.” – U of M professor Keith Fowke

Vaccine requirements are already gone, and indoor mask mandates are being removed March 15. The province, however, doesn’t expect a major rise in hospitalizations, intensive care unit admissions or deaths.

“I don’t think we’re going to see a new wave increase like we did previously,” Atwal told reporters March 2. “We’ll have a plateau and we’ll continue to bump along.

“The system has been preparing, and will continue to prepare, for potentially another wave. And I think that’s recognized that there might be another variant that comes along that might cause more severe outcomes. We don’t know that at this point… we’re going to continue to monitor that situation.”

The world has learned a lot about COVID-19 since March 2020, but there’s still so much unknown.

If we’re in this together then, as so many public health announcements declared, we need to get out of it together. That means understanding how new variants are emerging and keeping track of government ability not only to donate vaccine supply internationally, but to help with distribution, virologist Jason Kindrachuk conveyed in an interview in January.

“Ultimately, if we’ve learned anything out of this pandemic, and certainly out of Omicron (variant), it’s that we are all interconnected, whether we’d like to believe it or not. So what happens in one area of the world, as distant from us as it may be, it will have ramifications for us and for the rest of the globe.”

katie.may@freepress.mb.ca

Katie May is a general-assignment reporter for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.