Ukrainian influences are everywhere

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 07/03/2022 (1375 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In the face of unspeakable adversity, the world is currently witnessing the resilient and courageous character of the Ukrainian people.

A century ago, these traits would prove vital for the thousands of hard-working peasant farmers who came to the inhospitable Canadian west in search of a new beginning. As partners in a shared story, we on the Prairies have forged a deep connection with the people of Ukraine.

Today, this legacy shapes our towns and cities, physically manifested most prominently through Ukrainian religious architecture that has become an intrinsic part of many communities. Drive across the Prairies between Winnipeg and Edmonton, and you’ll find the characteristic domes of Ukrainian churches piercing the sky as often as the iconic grain elevators.

When the early settlers arrived in the 1890s, a small chapel that combined local construction techniques with traditional Ukrainian shapes was often one of the first buildings to be constructed. Amazingly, three of these tiny chapels still stand in Manitoba, including St. Michael’s Church at Trembowla, near Dauphin, the oldest remaining Ukrainian church in Canada.

Constructed in 1898 and measuring only 4 x 5 metres, the building has horizontal wood siding covering mud-plastered log walls, enclosed by a simple gable roof that is adorned with a tiny, handcrafted onion dome. As more Ukrainian settlers moved to the Prairies, most of these small structures would be replaced by more prominent wooden church buildings that are still commonly seen rising above cities and towns across the West.

After the turn of the century, Ukrainian immigrants began settling in Winnipeg, attracted by the boom in Canadian railway construction. They settled in neighbourhoods adjacent to the CPR rail yards, because employment could be found in railway construction crews, or in repair and iron works shops. This connection to the railway made Winnipeg’s North End a large Ukrainian residential enclave and is the reason so many iconic Ukrainian churches are found in the neighbourhood today.

Ukrainian and Jewish businesses were also instrumental in establishing Selkirk Avenue as the neighbourhood’s commercial high-street.

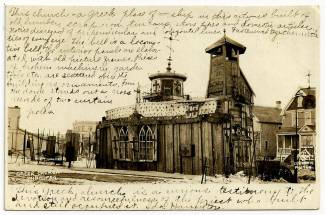

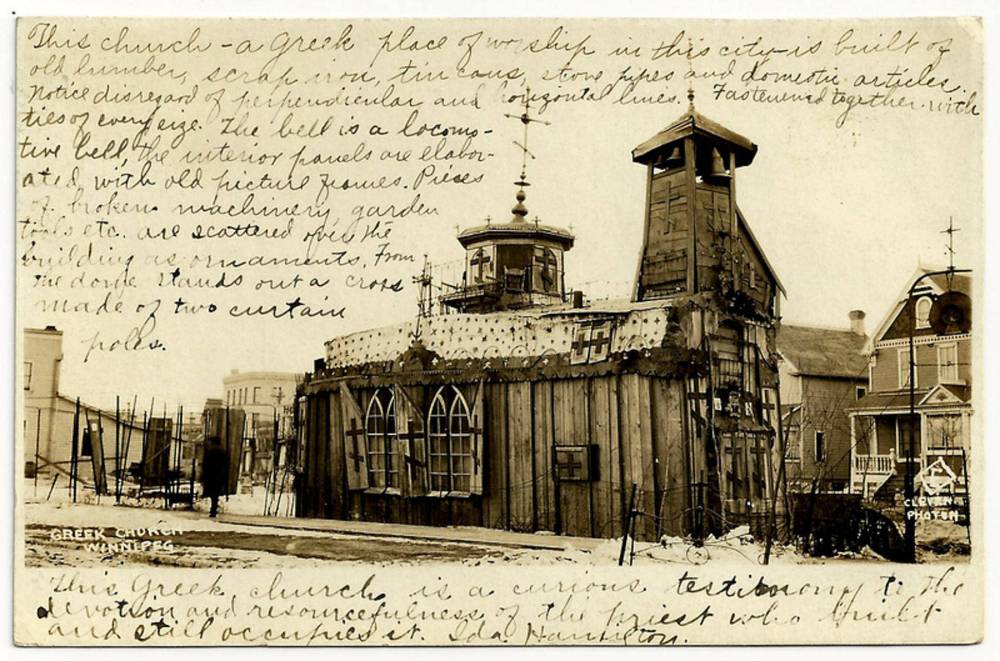

As the North End grew, small wooden Ukrainian churches began to rise at almost every corner. In 1904, one of the most unique buildings ever constructed in Winnipeg went up at King Street and Stella Avenue. A year earlier, a vagabond priest named Bishop Seraphim arrived in Winnipeg from New York and immediately found a following among Ukrainian Greek Catholics.

After he took over a small independent church on McGregor Street, the established churches reacted by orchestrating a coup while Seraphim was away. He returned from a trip abroad to find that he had lost his chapel, and responded immediately by starting construction on a building that came to be known as the Tin Can Cathedral.

He and his followers built the structure by hand, using anything they could find, resulting in what might be described as a giant piece of three-dimensional folk art. A post card sent at the time described it as “built of old lumber, scrap iron, tin cans, stove pipes, and domestic articles.”

The makeshift Tin Can Cathedral was destroyed by vandals after a few years, but it remains a reminder of the resourcefulness of Ukrainian people and is a unique piece of the North End’s history.

By the 1940s, Winnipeg had become the institutional centre of Ukrainian church life in Canada. As the community’s wealth and influence grew, the small wooden churches in the North End began to be replaced by great soaring edifices. In 1947, Ukrainian Catholic Metropolitan Cathedral of Sts. Vladimir & Olga began construction on McGregor Street.

Its vast interior space is one of the most breathtaking in the city, adorned with Leo Mol-designed stained glass windows and ornate decoration. Demonstrating that famous Ukrainian resourcefulness, the beautiful ceiling is made of a type of acoustic tile that you might find at the family cottage, disguised under spectacular painted murals.

The early 1950s saw other grand Ukrainian churches built in the North End, including Holy Trinity Cathedral, with its five onion domes rising dramatically over Main Street near Redwood. Its towering design was the result of a worldwide competition and was modelled after the Saint Sophia Cathedral in central Kyiv.

Representing a vibrant and forward-thinking community, later designs of Ukrainian churches in the North End evolved beyond traditional architectural vocabularies and stand as some of the most dynamic examples of Modernist architecture in the city.

The delicate lace towers of Saint Joseph’s Church on Jefferson Avenue near Main Street, and St. Nicholas Church on Bannerman Avenue, a stunning modern interpretation of the Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, are two of the finest Modernist buildings of any kind in the city.

Winnipeg’s North End, and countless towns across the Canadian Prairies, demonstrate the deep connection we have with the people of Ukraine. Our shared history is physically imprinted in the DNA of these communities, a reminder of a common bond that reinforces our support for them in a time of extreme hardship.

Brent Bellamy is senior design architect for Number Ten Architectural Group.

Brent Bellamy is senior design architect for Number Ten Architectural Group.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, March 7, 2022 10:55 AM CST: Adds images.