Freedom’s troubling toll For asylum-seekers, the dangerous trek across the Canada-U.S. border was just the beginning of an even harder journey

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 04/03/2022 (1471 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The first year was hard, but after that Subir Barman’s life began to fit together, like pieces to a puzzle that had been strewn all over the world.

He stayed in Winnipeg for a while. His refugee claim crawled through the system. He found a job at a St. Boniface factory; it had nothing to do with his expertise as an aircraft technician, but at least it was something.

Then he moved to Toronto, where he rented a house with other newcomers from Bangladesh, who were also trying to get a foothold in Canada. Soon he found work in his field, working on planes for a charter airline. His nephew came to Canada to study electromechanical engineering and lived with him.

When Barman was working, the hours passed quickly. When he was at home, he ached for his family.

It was worse after he broke his back in a car crash last September; he was off work after that, so all he could do was rest and heal and look forward to the day when his wife, Sreeti Rani Barman, and two children would finally join him.

By then, it had been more than five years since Barman had last seen them. When he fled Bangladesh, under threat of sectarian violence against Hindu people like him, his children were just eight and five years old.

Now his daughter Saptorshi was in her teens, and his son Sattik was 11. He’d watched them grow over video calls and Facebook posts.

This separation, he believed, was what he had to do to keep his family safe for the long run. He’d started in New York City on a working visa, where he met a fellow refugee-hopeful from Bangladesh, a Muslim man named Hossain who had faced death threats after writing against extremist terrorism. The two became friends, and planned to stay in the U.S.

But in early 2017, those plans suddenly changed. Donald Trump was about to take office as the 45th president of the United States, and had made clear his intentions to introduce harsher immigration restrictions. Like many others seeking safety in the U.S., Barman and Hossain worried the country would soon slam shut its doors.

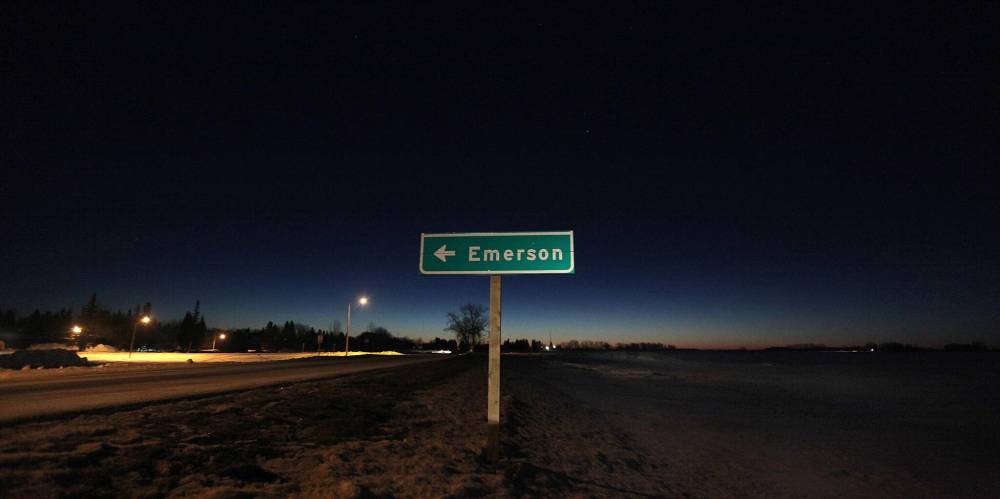

In February 2017, they made their move. They bought the best winter jackets and boots they could afford, and took a long bus journey to Grand Forks. They hired a cab to drive them within a few kilometres of the border, where they put on layers of sweaters. Then they began to walk, trudging four hours towards Emerson in the vicious -23 C cold.

That night, the first two Canadians Barman and Hossain met were local volunteers who tried to help people coming over the border. The third was the late Free Press journalist Randy Turner, who found the pair walking towards a motel. For the next week, a Free Press team followed them as they took their first hopeful steps in their new country.

Soon, the two men were living on cots at the Salvation Army, surrounded by others who had made the same desperate trek.

That winter, an unprecedented number of asylum claimants found a way to get across Canada’s southern border. They came from all over the world, many at the end of a journey that wound from Africa to somewhere in South America, and then to the U.S.

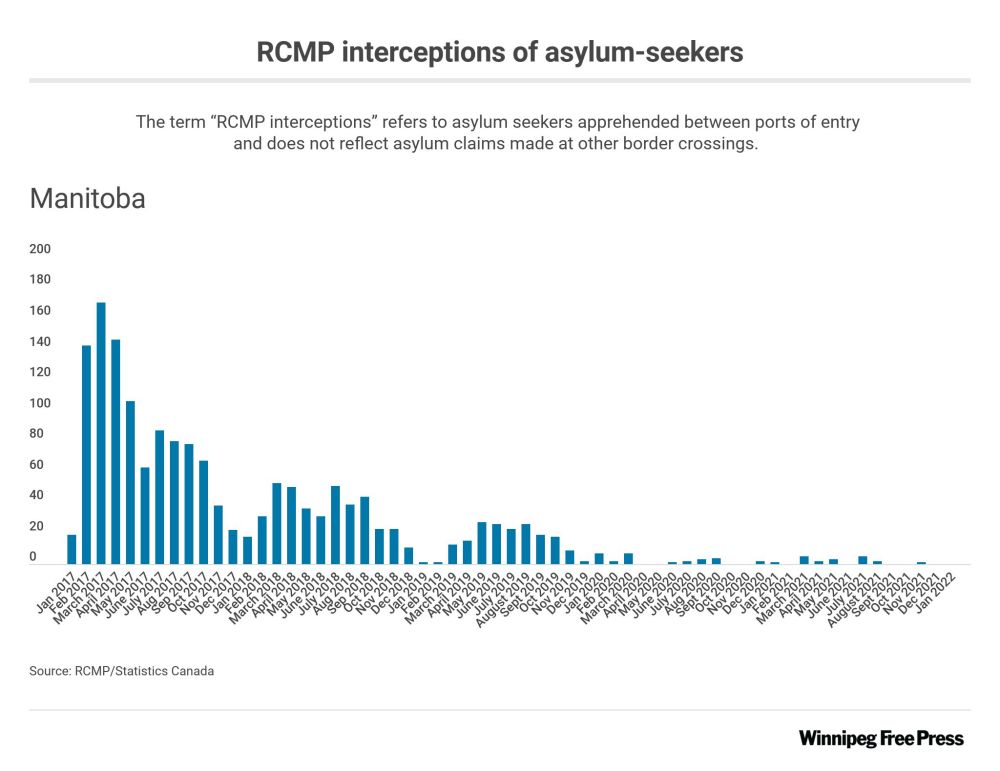

Between January 2017 and March 2018, at least 25,645 people who crossed the border irregularly came to the attention of RCMP, and the number of asylum applications Canada received more than doubled from the previous year.

The surge dominated Canadian headlines. At home, it sparked a political tug-of-war over the Liberal government’s perceived control of the border; abroad, it tied into the Trump-era news flood that was gripping the world. Television crews from as far afield as the United Kingdom and Japan came to Winnipeg to report on what was happening.

In the city, social-service agencies scrambled to make sure the new arrivals were fed and housed. They made urgent pleas for donations. When beds at newcomer service agency Welcome Place filled up, that organization turned to the Salvation Army, which set aside rooms at its downtown shelter; those beds were claimed, and still people kept coming.

The journeys they made to reach Canada were dangerous and daunting. Two men lost part of their limbs to frostbite, and advocates raised the alarm that the U.S.-Canada Safe Third Country Agreement, which stops most asylum-seekers coming over the land border from making their claim at a regular port of entry, was putting lives into danger.

In May 2017, those advocates’ worst fears were realized when Mavis Otuteye, a 57-year-old grandmother from Ghana, died of hypothermia as she tried to reach Canada. It is believed she was coming to make a claim, but also in hopes of meeting her first granddaughter, who had been born just days earlier in Toronto.

She was a warm and loving woman, her friends and family remembered, with a bright sense of humour and a special knack for making homemade sauces, which she sold at markets in Delaware while she lived in the United States. She died alone in a drainage ditch in Minnesota, less than a kilometre from the border.

But most who set out for Canada made it through to relative safety, and from there, their stories were just beginning.

In the years since, few of the folks who came over the border stayed in Winnipeg. Most dispersed across Canada, settling in Toronto or Calgary or Vancouver.

If their asylum application was approved, they began, like Barman, to try to rebuild their lives and pull their families back together; if it was rejected, they began the long road of an appeal.

Some were eventually deported; others found themselves caught in limbo, their applications fallen through the cracks due to delays by overwhelmed lawyers or the finer points of immigration law. A freeze on deportations to Somalia meant that some from there are now stuck in a legal purgatory, eking by on work permits but unable to plan for an uncertain future.

Most Canadians didn’t see all that, though. Soon, the stories slipped from the headlines, and the crisis was forgotten almost as quickly as it began. For all the headlines the surge seized in 2017, it made relatively few long-term ripples in the public mind. The treaty that pushed people to risk their lives to cross the border stayed in place; it was actually strengthened.

But people continued to make those desperate journeys. Between April 2020 and September 2021, despite a pandemic rule stopping people who enter Canada outside a regular port of entry from making a claim, 1,429 did just that. Most were sent back to the U.S., where some found themselves facing deportation to the countries from which they had fled.

And in January, when a family from India perished in snow-blown fields near Emerson as they tried to reach the U.S., there was a moment when the perilous journey was back in the news; but just 10 days later, a convoy of protesters reached Ottawa, and after that there wasn’t enough oxygen in Canada to talk about much of anything else.

It has been five years now since those first headline-making events. So maybe there ought to be time to reflect.

When Abdikheir Ahmed thinks back to those frantic months in 2017, the first thing he remembers is the fear. It hasn’t left him.

As people kept trickling over the border that winter, Ahmed was terrified for them. Many were alone, he knew. Their families often didn’t know exactly where they were, or what they were trying to do.

“The amount of fear that I had of folks freezing to death in farmlands, and nobody knowing they actually even died in there,” he says.

“You can have a smuggler drop you there, and if you die in the farmland, nobody knows that you actually died there. That was my biggest fear. That’s the main thing I still remember about it.”

But the second thing he remembers is how the community responded. He remembers churches in Gretna and Altona that prepared places for newcomers to stay. He remembers donations of food, and clothing, and shelter. He remembers nearly two dozen non-profits that collaborated to make sure everyone who came got what they needed.

“It was quite incredible how people came together so quickly,” he says.

Ahmed himself had a key role in building those connections. Partly, it was his job; at the time, he served as co-ordinator with Immigration Partnership Winnipeg, and was also a board member for the Immigrant and Refugee Community Organization of Manitoba — better known as IRCOM — which was also on the front lines of supporting asylum-seekers.

But it was also a deeply personal mission. Born in Somalia, he had come to Canada as a refugee in 2003, and had devoted much of his life to helping newcomers find their place in the broader Manitoban community. In 2016 those efforts were honoured when the province bestowed him with the esteemed Order of the Buffalo Hunt.

So as the number of people seeking asylum surged that winter, Ahmed raced to do everything he could to help.

“Folks are running away from persecution,” says Ahmed, who is today the executive director of the Aurora Family Therapy Centre.

“If you’re a refugee claimant you get one chance. I really want to make sure that when people have one chance, that they make use of that opportunity to get what the legislation accords them.”

“If you’re a refugee claimant you get one chance. I really want to make sure that when people have one chance, that they make use of that opportunity to get what the legislation accords them.”–Abdikheir Ahmed

While the community banded together on the ground, the fault lines in the public debate cracked wider. Ahmed recalls the comments on news websites calling asylum claimants “vermin.” He recalls the politicians who cast doubt on the claimants’ motivations. He attended a media debate that, he recalls, pondered whether Canada should close its border.

Overall, the public discourse was tense, and thick with falsehoods and misconceptions. He was dismayed.

“Even in the media itself, there were a few folks who were interested in driving a wedge between the people who were seeking protection and the local community,” he says. “People see the headlines, and they get swayed by a quote that someone puts out there.”

To bridge those divides, Ahmed and others decided they needed to speak with border communities directly. They formed a working group, called the Refugee Public Awareness Coalition (Manitoba), which created a workshop kit called Bread and Borders, designed to facilitate constructive conversations focusing on the fears people had about refugees.

That’s how, in early 2017, Ahmed and several colleagues found themselves in an empty hall in Altona, about 12 kilometres from the American border, wondering if anyone would show up. They’d heard of some hostile reactions in the community, and while they set up for their presentation, they thought about the kind of reception they would receive.

“Me and my friends are saying, ‘Are we going to be chased out of here?’” he recalls.

Minutes before the event was to start, a few people trickled in. Then a few more followed, and more again, and by the time Ahmed and his friends started their presentation, every seat was taken.

Many folks went to presentations like these because they wanted to help the newcomers, but some were apprehensive and had questions about what was happening at the border.

What seemed to work, Ahmed says, was gently correcting their misconceptions. There were many. Some believed claimants were trying to sneak into Canada, for instance, which to them carried a whiff of the nefarious. In fact, the opposite was true: asylum-seekers wanted to present themselves to Canadian authorities in order to begin their claims.

Other people, including some politicians, accused the claimants who came over the border of “jumping the queue.”

But there is no queue; their claims are processed through a different stream than other forms of immigration, and refugees outside the country are selected for resettlement by something closer to a lottery system, which political critics surely knew.

As conversations like these spread across Manitoba, Ahmed saw the divisions in the community soften. Five years later, he remembers far more help offered than resistance given.

“Certainly there is space for people to learn, and there are quite a few people who learned a lot from that influx,” he says.

But that opens a question: if the same thing were to happen again, would the lessons of 2017 remain? Or, if there should be another surge of people seeking safety by making irregular crossings over the border, one that made international news and required a co-ordinated effort to meet the needs of all the newcomers, would the same tensions spring up again?

“Things dissipate from people’s minds when they’re not in the news,” he says. “But at the time, a lot of people understood…. While we had a few people who were quite negative in terms of welcoming folks who were fleeing the policies of the Trump regime at the time, a lot of folks were opening their doors, were supporting, were welcoming.”

Sometimes, he still thinks about those fields divided by the invisible line of the border, frozen and full of unvisited corners, and he wonders what could be out there that we don’t know.

He wonders whether someday, some farmer will discover the bones of a person who died there alone, years ago. Someone who perished in the hope for a country that spoke of protection, but pushed those who sought it into the cold.

When Abdul Razak Iyal set out through the snow that night, Christmas Eve 2016, he didn’t know about the agreement that meant he could not present himself at a regular crossing. He also didn’t know that, by the time his walk was over, he would be forever changed, and have become the face of a new wave of people desperately trying to reach Canada.

All he knew is that it had been nearly five years since he’d fled Ghana, fearing for his life in a family conflict. He’d travelled first to Brazil and then to the United States. Along the way, he’d met up with others in the same position. One of them was also from Ghana, a younger man named Seidu Mohammed; the two set out for the border together.

That night, as they trudged towards Canada, their hands froze. Mohammed lost all of his digits; Iyal lost his fingers, but was able to keep his thumbs. In the days after they were rescued, their stories plastered local media: they were among the first of the winter’s surge, and their life-altering injuries highlighted the peril asylum-seekers were facing.

Five years later, Iyal has settled into his life in Canada. He’s a permanent resident now. He has an apartment in a bright new building in West Broadway where Mohammed also lives; the two are still close friends. Recently, he was called back to work at a local hotel, where he’d been laid off when business collapsed near the start of the pandemic.

The night that he crossed is so fresh in his mind, there are moments he can’t believe that half a decade has passed.

“Time is running so fast,” he says. “You just take one night that I lost everything about my life. Sometimes when I sit down and think of that, I say ‘Wow, that’s how the world is going so fast.’ Thinking of that night until now is almost five years and some months and days? I’m in shock. I’m trying to stay the course, and trying to make sure to be strong and independent.”

While others who flooded over the border in those months scattered across the country, Iyal and Mohammed stayed. They were helped by so many people here, they wanted to give back. Within weeks of leaving hospital, Iyal began volunteering at a local mosque, where he’s helped with clothing drives for street-involved people, as well as other community groups.

”I have such a belief that everything happened for a reason,” he says, chatting last week in a bright communal space in his apartment building. “I have to give back to what I can do. If I don’t have physical money to give, I can use my strength to make sure I’m also helping people, to make sure that I contributed.”

But life here hasn’t always been easy, especially as he learned to adapt to the loss of his fingers. He used to drive forklifts, for instance, but he can’t do that now. And there are still moments in daily life where he finds himself struggling with things that once came easily, but over time he’s learned how to get by.

“I’m still doing things that I know I can do it perfect with my hands, but now without my fingers, sometimes when I’m doing something that I cannot do properly, I’m getting frustrated,” he says. “I know what I can do. But now I cannot do it the way I could do.”

He sighs, and continues.

“But I can’t change it. It already happened. I should let it be the way it is, and think about what I can do now. That’s the most important. Forget about the past. Think of what you can do now, and make sure you try to make something better for your life and the people around you.”

One way to help, he found, was by using his voice. When Iyal was rejected for jobs, he often wondered if his disability played a role; that made him want to support others in similar positions. In the years since his arrival, he’s worked with the Society for Manitobans with Disabilities, and tries to bring attention to the hardships so many Manitobans face.

“It’s not only about me, it’s about a lot of people who are on disability,” he says. “People who are going through a disability, it’s very hard for them to get a position, or get a type of job that they want to do.… We have to come together to make sure that we help people that are going through this situation, and make a better place for them.”

Of all the challenges Iyal faces, none is greater than the fact that his family is still not with him. After his refugee claim was approved and he became a permanent resident, he began working to sponsor his family, including his wife, mother and 17-year-old stepson. Last fall, he discovered that a small error in the application meant starting it over again.

But at least he was finally able to see them after nearly a decade apart; although he cannot return to Ghana, last year he was able to spend two months with his family in neighbouring Togo. It was an emotional reunion.

“It was very amazing,” he says. “It’s been a long time that I didn’t see my mom, that me and my mom didn’t sit down and talk as mother and son. So last year… seeing me alive, she was very relieved.”

Over the last five years, Iyal has told this story over and over, happy to give time to anyone in the media who asks. In recent weeks, he’s worked with a journalist from Minnesota and done interviews for local television and radio. When asked why he is still so open to telling his story, he thinks for a moment, and then points to the wider picture.

“It’s because the immigration system in both America and Canada is still the same,” he says. “Nothing has changed. People who are refugees, they want a safe place to live a better life. They want a place that they can call home, and they want a place they can call a community.

“So what are the governments supposed to do?” he continues. “Governments are supposed to make sure these people are safe and protected. That’s the most important thing. Forget about what the person is going through. You have to protect the person first, before everything that comes after.”

“Forget about what the person is going through. You have to protect the person first, before everything that comes after.”–Abdul Razak Iyal

In the months after he came to Canada, he learned more about the system through which he had entered. In particular, he learned about the Canada-United States Safe Third Country Agreement, a 2004 treaty which requires most people seeking refugee protection to make their claim in the first of the two nations in which they arrive.

But the agreement does not alter the right hopeful claimants have, to seek asylum after they have already arrived in Canada. In short, the agreement doesn’t prevent people coming to Canada from the U.S. from making a claim; it only prevents them from doing it at a regular crossing, which pushes them to find another way to get over the border.

If it were not for the agreement, for instance, once Iyal and Mohammed decided they could not remain in the United States, they would have been able to go to any usual border crossing and tell officers they wanted to make a refugee claim. Instead, they had to get inside the country before they could begin the exact same process.

That latter point must be emphasized, experts say, in order to understand the situation. While some still refer to people who crossed the border outside of a port of entry as “illegal” immigrants, the truth is the process they are seeking is entirely legal: Canadian and international law enshrines people’s right to reach a territory and make a claim for asylum.

“It’s a misunderstanding that it’s an illegitimate claim to protection when they cross the border, and yet that’s the actual legal right,” says University of Winnipeg professor Shauna Labman, a scholar of refugee law. “That’s the commitment in international law, that’s the commitment in our Immigration and Refugee Protection Act.

“There’s this perception that the public has that there’s an illegal process, that they’re breaking law, but.… The point is to make yourself known and make that claim. If it’s accepted, it’s a slow process, but they can work on bringing their family here. It’s not a hidden system, where they’re trying to hide from the law or government. They’re just seeking protection.”

In a way, the events of 2017 were one of the first times Canadians had been forced to truly look at this process. Surrounded by three cold oceans and a relatively quiet land border with the United States, the country had never faced the kind of flows of human beings seeking safety that had long surged and subsided elsewhere in the world.

For years, Canadian governments had touted themselves as champions for refugees via the nation’s resettlement programs, which process people abroad before bringing them to Canada. But the cornerstone of refugee law, Labman says, is the core right to allow people to get to a place of safety, and make their claim as being a person in need of protection.

And in Canada, the Safe Third Country Agreement challenged their ability to do so safely.

In the early 2000s, when the agreement was first being negotiated, refugee advocates warned it could lead to an increase in irregular crossings and even deaths. The agreement was passed with Canadian officials stating it was needed to control the border and limit the potential number of people coming to Canada to make a claim.

So in 2017, as the number of people trying to reach Canada surged, the agreement was back in the spotlight. The death of Mavis Otuteye highlighted the risk; so did the injuries that Iyal and Mohammed suffered. Yet the law did not budge. The Canadian government stood by its position that the agreement was necessary to manage the border.

In 2019, it was strengthened, adding a new provision: if a person makes a refugee claim in any of the so-called “Five Eyes” countries — the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand — they cannot make a claim in any of the others. Information-sharing means anyone who tries will be deported.

“The Safe Third Country Agreement is really endangering people’s lives,” Ahmed says, glumly. “You could actually have an orderly way of people coming through the border and they get processed without any problems. Now they’ve actually made it worse.”

The goal of this is to prevent what Canadian officials have called “asylum shopping.” But it also raises more questions: what if the political situation in those other countries means that refugees’ legal rights are not being protected? For that matter, is it constitutionally tolerable if some who make a refugee claim in Canada receive a full hearing, while others do not?

Advocates have long challenged the treaty through the courts. In December, the Supreme Court of Canada agreed to hear arguments against its constitutionality in a case brought by the Canadian Council for Refugees. It will also revisit several applications made by refugee claimants who were denied because they had come from the “safe” United States.

But that agreement is part of why Iyal is still so willing to speak to reporters. For him, the danger has passed; for others, it still lies ahead. He thinks about those who continue to risk their lives to go over the border. And about Otuteye, who died months after he crossed. And about the family from India that perished in January. Especially the children.

“We lost our fingers, but these people lost their lives,” Iyal says. “That’s the most difficult part. The government of Canada has to do something about it. We can’t continue people losing their fingers, or losing their lives. That’s not who Canadians are, and that’s not who Americans are. Canadians want everybody to be safe.

“So they have to do something about it, to make sure they are protecting these people.”

”We can’t continue people losing their fingers, or losing their lives. That’s not who Canadians are, and that’s not who Americans are. Canadians want everybody to be safe.”–Abdul Razak Iyal

On a wintry day in late January, Subir Barman’s wife and their two children landed at Toronto Pearson Airport after a long journey out of Bangladesh. Barman could not embrace them, because they had to start quarantine, but he still met them off the plane and felt a surge of joy and relief.

His friend Hossain, with whom he’d walked over the frozen fields to safety in Manitoba five years ago, was beside him.

The early days of the family’s reunion passed quietly, at home. Barman began looking for a house to rent for just the four of them; his wife made arrangements to take English lessons at a local community centre. They began planning for the kids to start school, where they will begin an English as an Additional Language program.

The kids weren’t thinking about school too much, though. They were excited to see more of Canada. When their quarantine was over, the family went to a Hindu temple to mark Saraswati Puja, a festival to mark the coming of spring; days later they drove to Niagara Falls, where they took smiling photos in front of the thundering water.

The future is still uncertain, but every day the picture gets a clearer. Barman is getting regular physiotherapy to deal with his back injury and hopes to return to work in the fall. Five years after he walked into Canada, he and his family are permanent residents. Five years from now, his daughter will be a university student, and they could all be Canadian citizens.

“I will make it, no problem,” he says.

And one night, just a few days after the family arrived, Barman watched as his son, 11-year-old Sattik, stood grinning in the driveway of the rented house, in front of cars dusted with snow. The boy had never seen snow before the night he landed in Canada, nor had his sister. Barman raised his phone, and snapped a photo to remember the scene.

In the image, Sattik is waving a hand to sky, and his eyes are shining. Once, five years ago, his father made a perilous march through the snow, on a night when the cold threatened to steal his limbs or his life. Because of that journey, his children can now look at the snow and see only a world of delight.

“They’re really excited,” Barman says. “They want to play in the snow, but they don’t have enough gloves and boots. So I told them, after you finish quarantine, then I will buy for you. Then you can go into the snow, because without snow boots, if you go there, you might slip.”

melissa.martin@freepress.mb.ca

Melissa Martin

Reporter-at-large

Melissa Martin reports and opines for the Winnipeg Free Press.

Every piece of reporting Melissa produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.