Newborn apprehensions plummet but work remains: advocates

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 25/01/2022 (1413 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Manitoba has recorded a drastic drop in the number of newborns entering foster care, newly obtained data show. However, Indigenous advocates say more needs to be done to end the discriminatory practice of birth alerts for good.

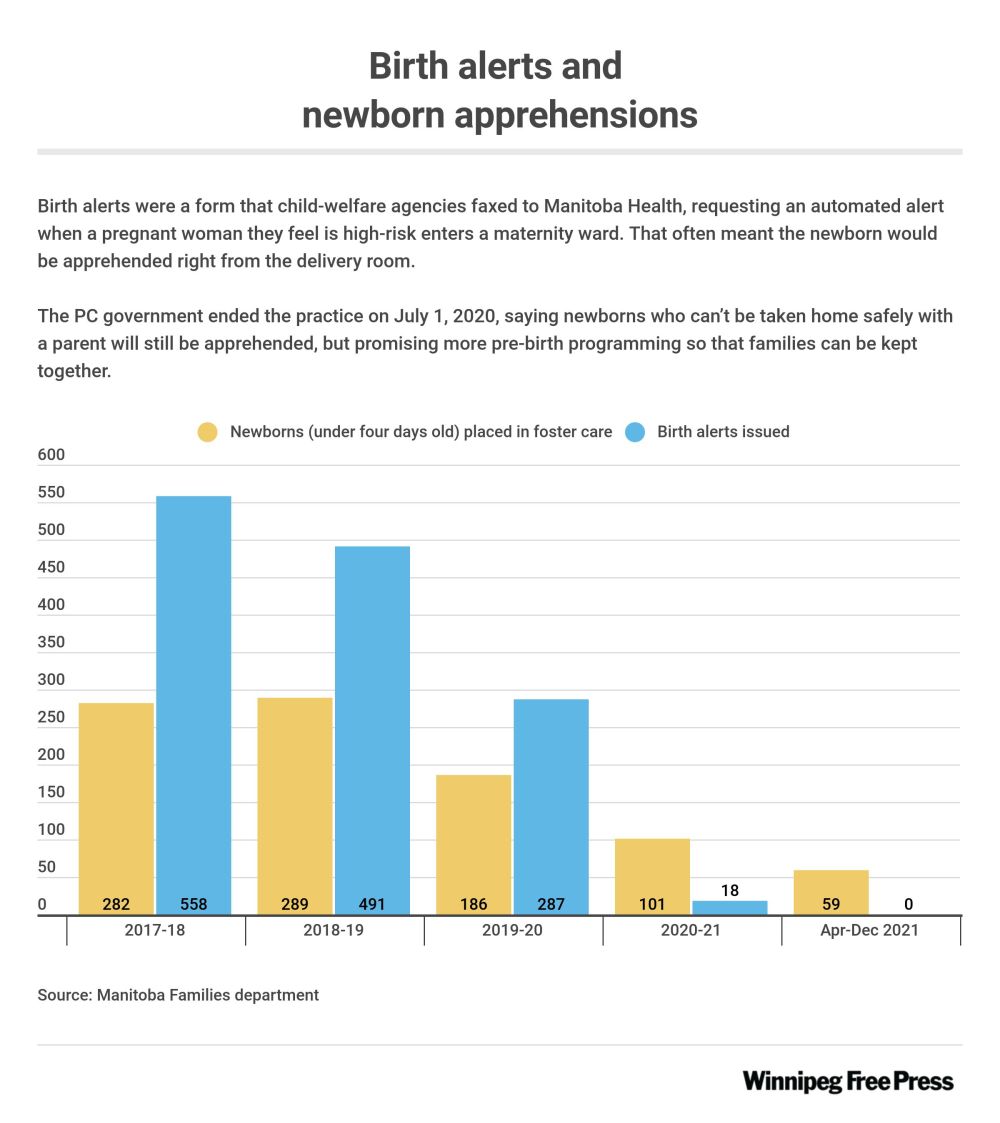

For years, Manitoba led the country in the proportion of children in care, who are still overwhelmingly Indigenous. Part of that stems from decades of child-welfare agencies using birth alerts — a form they would fax to Manitoba Health, requesting an automated alert when a pregnant woman they feel is high-risk enters a maternity ward.

Child-welfare agents used criteria that often included any prior involvement in foster care or even accessing welfare while pregnant.

For hundreds of women a year, that meant having their children taken by government workers right from the delivery room.

“Coming out asking for help shouldn’t result in you losing your child forever or for any period,” said Diane Redsky, head of the Ma Mawi Wi Chi Itata Centre.

“Coming out asking for help shouldn’t result in you losing your child forever or for any period.”– Diane Redsky

The Progressive Conservative government formally ended the practice of birth alerts July 1, 2020. Existing laws would still have newborns apprehended when they can’t safely be taken home with parents, but the government pledged more pre-birth programming so more families could be kept together.

In the fiscal year ending March 2018, Manitoba had issued 558 birth alerts, with about half (282 newborns) ending up being placed into foster care within their first four days of life.

That number has gradually dropped, with 186 newborns placed into care in the fiscal year ending March 2020.

Fresh data obtained by the Free Press show Manitoba is on track to have less than 100 newborns taken into care during this fiscal year.

In the fiscal year ending March 2021, 101 newborns were placed into the foster system. Between April 1 and Dec. 31, 2021, 59 newborns were taken into care.

In the fiscal year ending March 2021, 101 newborns were placed into the foster system.

In an interview, Families Minister Rochelle Squires attributed the drop to a reform that unpegged child-welfare funding amounts from the number of children taken into care.

The idea is to boost preventative programming, to cut down on the trauma and added taxpayer expense of putting children into a new home. Advocates generally support changing the funding model, but warned the new formula — dubbed single-envelope or block funding — results in agencies receiving less cash overall.

“Ending the practice of issuing birth alerts doesn’t mean the end of any newborn apprehension, but what it does do is end that discriminatory practice that was not serving communities and families well at all,” Squires said.

“In fact, it was likely further stigmatizing them and in many cases causing mothers to not reach out, to get the support and help that she needs to be successful in raising her children.”

Redsky said it seems the system is gradually improving.

Her staff at Ma Mawi in Winnipeg find agents for Child and Family Services are more receptive during pre-birth meetings with expectant moms.

Staff from the Indigenous outreach centre help moms craft a plan to show that she has enough supports from relatives and community groups to successfully parent. The agents review that plan, and suggest other services that could help.

“They’re having more meaningful conversations with CFS agencies when there is a concern about a mom taking her baby home from the hospital,” said Redsky.

Far fewer moms end up having their child taken away, but Redsky said it’s unclear if that’s due to the province’s gradual reforms or the COVID-19 pandemic changing how foster care works.

Squires argues her government is making progress by funding prevention work by community organizations at-risk moms will feel comfortable accessing, which can range from kicking an addiction to simply finding babysitting.

For example, the Mothering Project at Mount Carmel Clinic in Winnipeg offers nutritional counselling, a pre-natal clinic, daycare and Indigenous ceremonies. Another project in the city’s North End, Granny’s House, offers to temporarily look after Indigenous children so parents can do errands or have a break.

“What we really need to do is have a stronger focus on some of the prevention initiatives that we’re already starting to see some really good results from,” Squires said.

Redsky said those changes are a stop-gap to true reform, where Indigenous governments have autonomy over child welfare.

“Until they have full control, we’re always going to be within a system that is designed to set up to make us fail,” she said.

Redsky herself was in foster care as a child, and might have been the subject of a birth alert two decades ago at HSC Women’s Hospital.

“There was social workers sniffing around the hospital when I (gave birth to) my son back in 1998,” she said. “Being Indigenous, I’m sure there was also some racial profiling contributing to that.”

“There was social workers sniffing around the hospital when I (gave birth to) my son back in 1998.”– Diane Redsky

Redsky was part of a 2018 legislative review commissioned by the PCs, which argued Manitoba’s social systems use criteria that work against First Nations and Métis.

“Until we change the rules, regulations and standards, we will always have a system that will work against Indigenous families.”

To that end, some Indigenous governments want to take authority over child welfare through a bill the federal Liberals enacted in 2019.

Squires said the pandemic has delayed talks between Ottawa and Manitoba aimed at clearing hurdles for that process to take effect, such as figuring out funding formulas and who would gain access to child predator registries.

But she said both governments are committed to devolution.

“Jurisdiction over their child welfare will certainly allow many Indigenous governing bodies to repatriate their children, and they’ll be, I believe, tremendous outcomes through that transition,” she said.

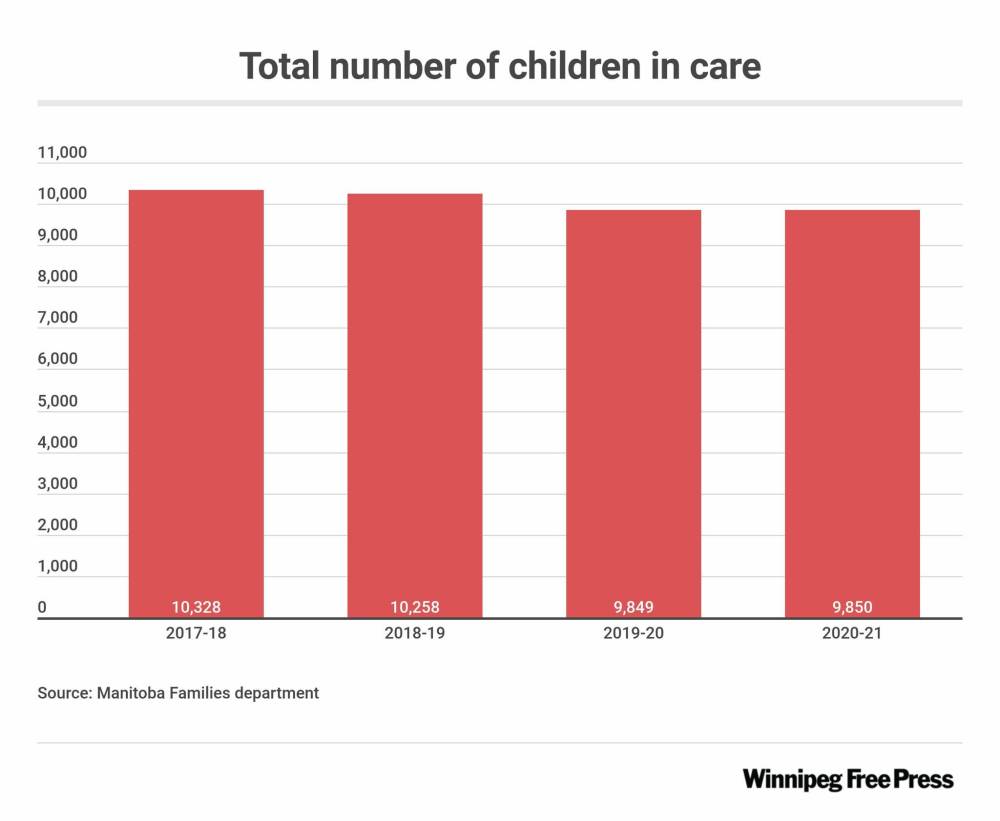

Internal data show a downward trend in children coming into foster care across all age categories. But Squires said her job isn’t done until newborns are all kept with their families.

“Because we’re still seeing newborn apprehensions, we still have a ways to go,” she said.

“We need to continue on, until we’re seeing all families supported well enough to stay together.”

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca

Manitoba scraps pandemic reporting on foster care

Manitoba Families has stopped issuing recurring reports on the state of foster care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Instead, the province will only provide snapshots on the state of child welfare once a year.

Starting in March 2020, as the novel coronavirus took hold in Manitoba, the department issued reports that summarized trends in apprehensions, kids aging out of child welfare and how many wards of the province had caught COVID-19.

The Free Press obtained all these reports through a series of freedom-of-information requests, in order to monitor the pandemic’s impact on foster care.

The province updated this internal dashboard monthly, before switching in February 2021 to quarterly reports. The department suspended its dashboard in June 2021.

“It became clear after experience with this dashboard that this information couldn’t be tracked on a quarterly basis, in a manner that would ensure the accuracy and completeness of the data,” a spokesperson wrote Monday.

The department said it extensively verifies data with the four authorities that control child welfare in Manitoba when it does annual reports, but couldn’t do the same every three months.

“Trends of children in the CFS system during the pandemic are available through a number of sources, including the department’s annual reports and CFS authority annual reports.”

—Dylan Robertson

History

Updated on Tuesday, January 25, 2022 10:29 PM CST: Updates date range of graphic