Domestic diva In the 1930s, Free Press readers turned to Mrs. Madeline Day to help them get dinner on the (perfectly set) table

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/01/2022 (1509 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

The dining room was set with fine china, gleaming silverware and crystal glasses. A lush bouquet bloomed at the centre of the table, while a canary chirped merrily in a nearby cage.

Ingredients for the afternoon’s feast were chilling in the kitchen’s electric refrigerator and a wealth of cookware was poised for action next to the state-of-the-art range.

This is the first story in our Homemade series, which will look at the Free Press’s history through its food content, while also sharing modern recipes and food stories from Winnipeg.

These features will be compiled into a community cookbook, alongside recipes submitted by local residents.

Learn more and share a recipe at Homemade.

Mrs. Madeline Day was ready to entertain and soon, her guests would arrive. All 4,100 of them.

On April 2, 1935, droves of local women flocked to the Winnipeg Civic Auditorium to hear Day lecture on the proper way to roll a pie crust and the virtues of washing with Lux brand soap.

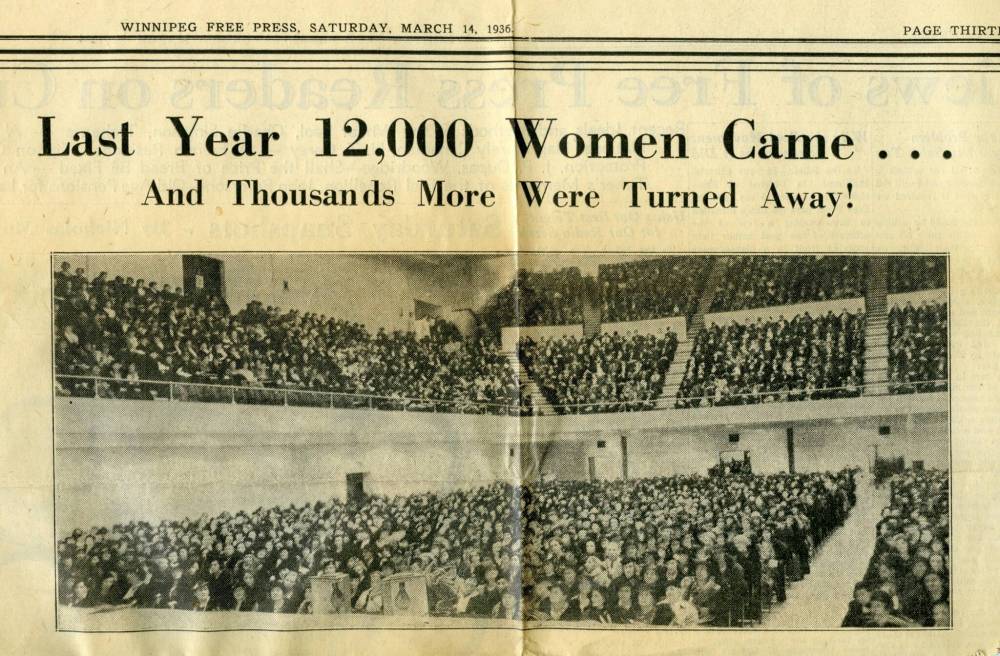

The inaugural Free Press Cooking and Homemaking School lasted three days and was one of the largest conventions held at the Vaughn Street auditorium — now home to the Archives of Manitoba — in the three years since its opening.

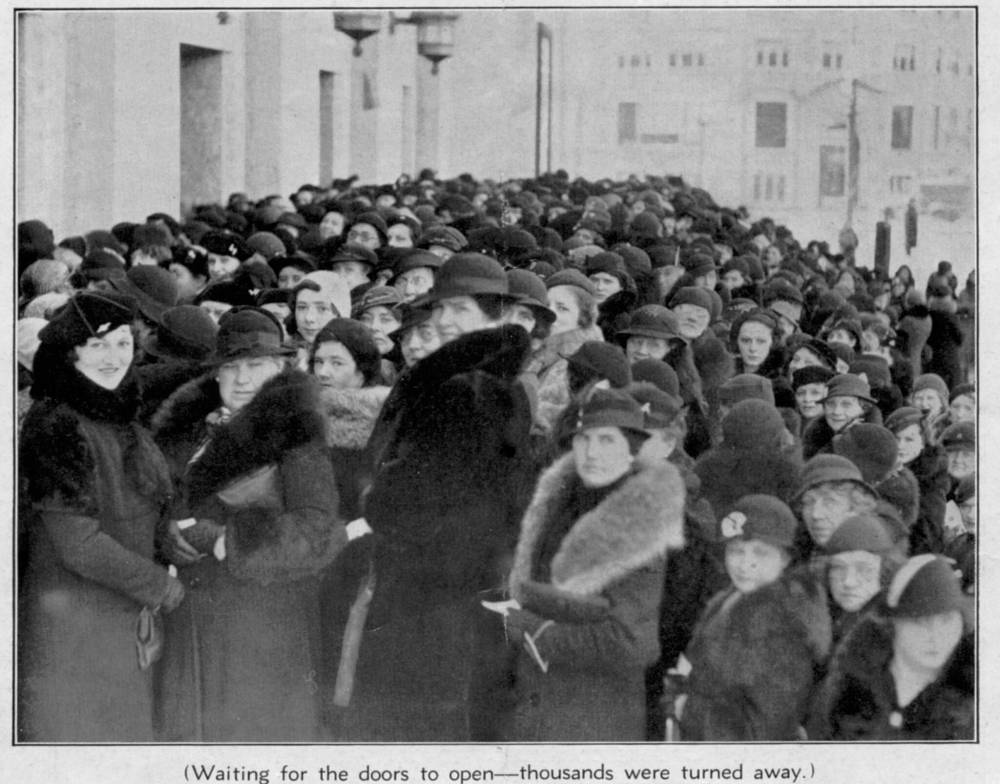

Young fiancées, housewives and grandmothers lined the block and one “white-haired little woman, whom you felt would be a born cook and possess a most delightful home,” arrived two hours early to snag a seat in the front row, according to an account from the day.

Admission was 10 cents and the events were so popular the newspaper issued a formal apology to the hundreds who were turned away at the door. Day, the Free Press’s new cooking columnist, was the main attraction.

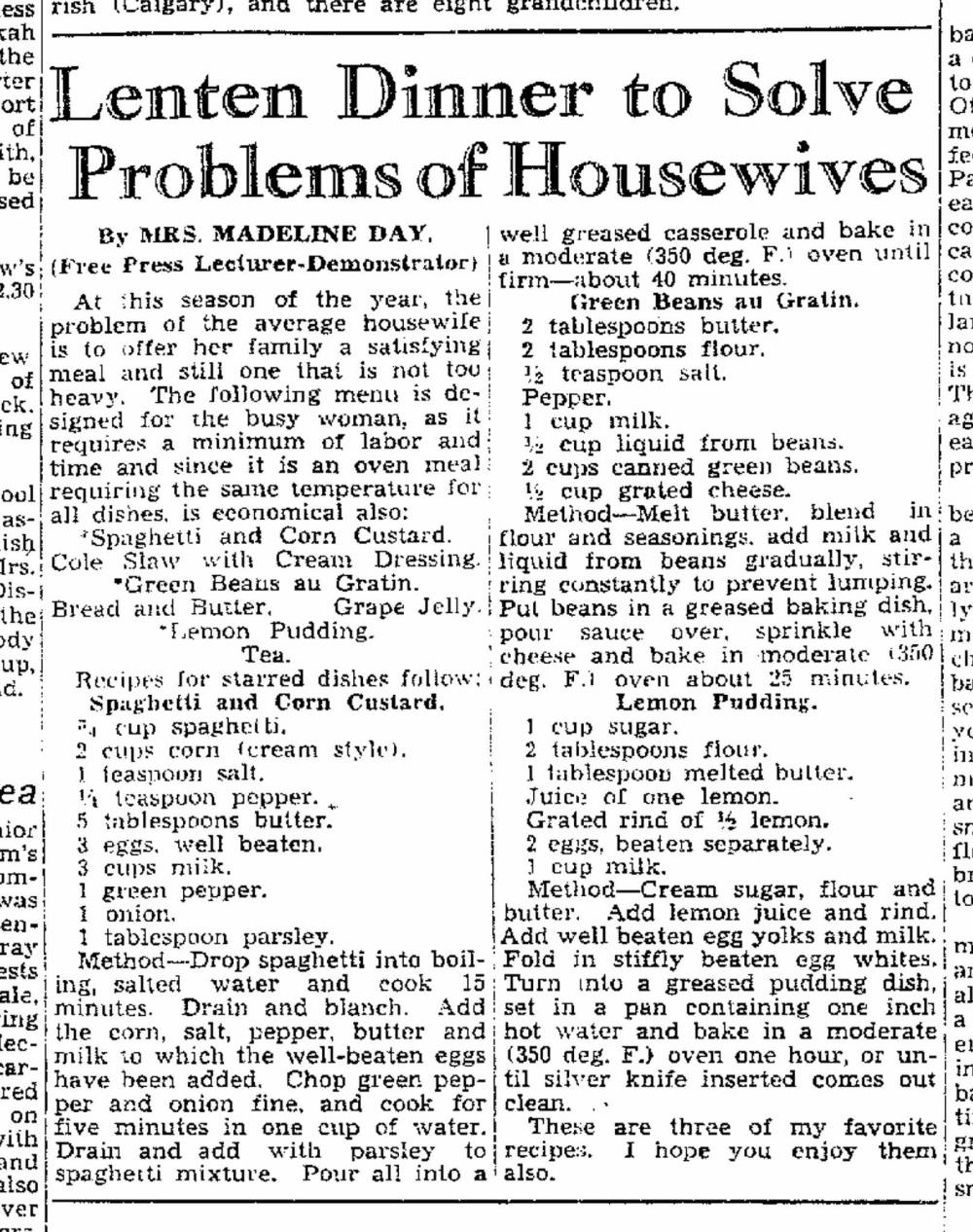

Billed as a domestic sciences expert, she hosted two cooking demonstrations daily from a stage made to look like a model home.

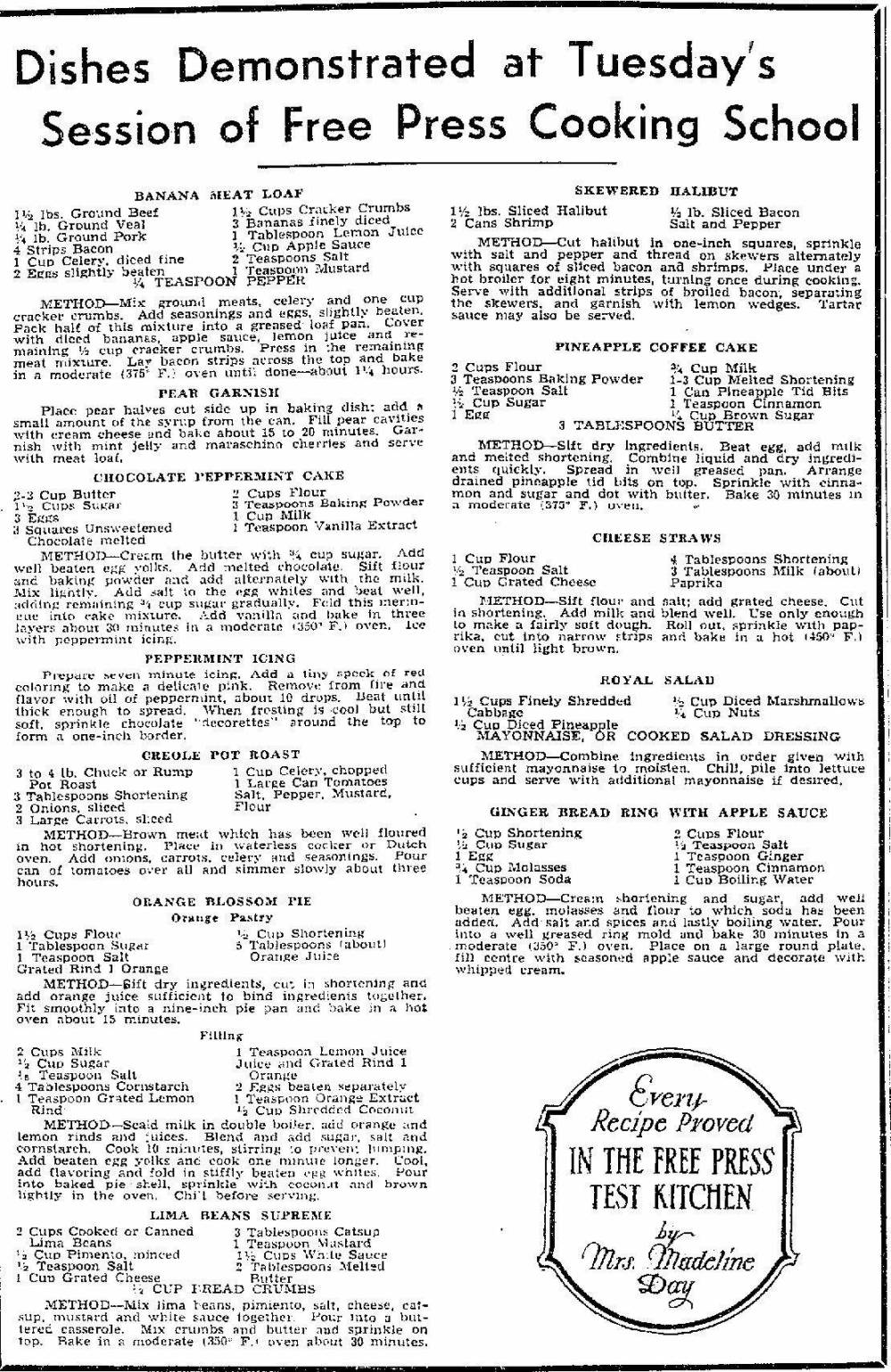

The first workshop opened, naturally, with a group singalong, followed by a whirlwind presentation of 10 inventive and economical recipes, including a banana meatloaf (which is exactly what it sounds like), a lima bean casserole, a royal salad and a pineapple coffee cake.

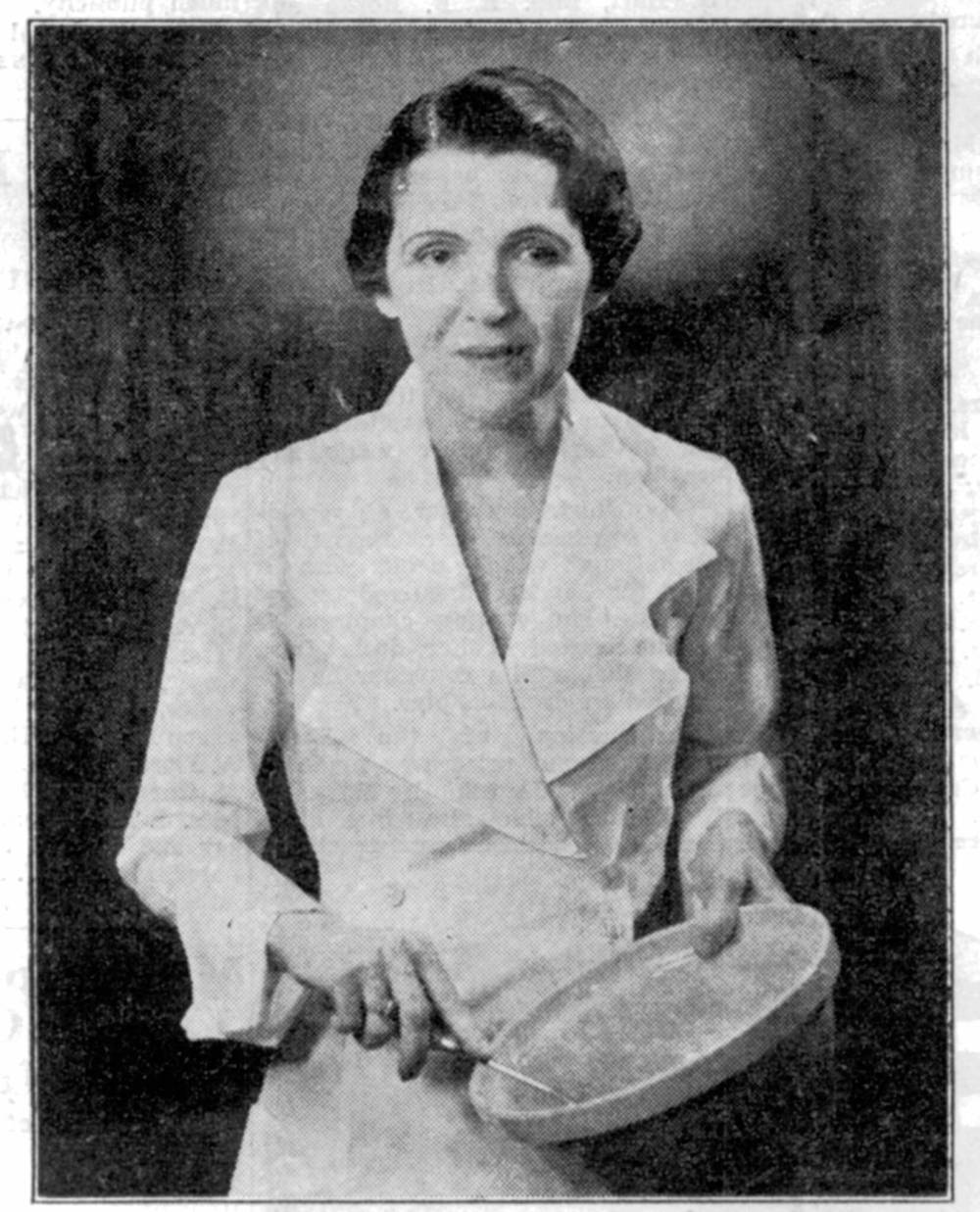

As a lecturer, Day, 43, was warm, matronly and engaging. She wore a crisp white frock with her brown hair done up in fingerwaves. The audience hung on every word, scribbling frantically in notebooks as their demonstrator flitted about the stage mixing ingredients and dispensing valuable cooking tips.

While making the aforementioned meatloaf, students were advised to do away with their forks, as the dish, according to Day, could only be mixed properly by hand.

An optional spoonful of Marmite added extra flavour and “nourishment” to the recipe and Keen’s mustard powder, interestingly, could be used as a kitchen seasoning as well as dissolved in bathwater to ward off colds.

An audible gasp rippled through the auditorium when Day unveiled the finished loaf, filled with diced banana, topped with bacon and browned to perfection. The dish was served with baked canned pears filled with cream cheese and garnished with maraschino cherries and mint jelly.

Mrs. Madeline Day’s Banana Meatloaf

Beef, veal and pork meatloaf is topped with bananas and applesauce and served with a pear garnish.

Ingredients

1 1/2 lbs Ground beef

1/4 lb Ground veal

1/4 lb Ground pork

4 strips Bacon

1 cup Celery, diced fine

2 Eggs, slightly beaten

1 1/2 cups Cracker crumbs

3 Bananas, finely diced

1 tbsp Lemon juice

1/2 cup Apple sauce

2 tsp Salt

1 tsp Mustard (powder)

1/4 tsp pepper

Method

Mix ground meats, celery and one cup cracker crumbs. Add seasonings and eggs, slightly beaten.

Pack half of this mixture into a greased loaf pan.

Cover with diced bananas, apple sauce, lemon juice and remaining 1/2 cup of cracker crumbs.

Press in the remaining meat mixture.

Lay bacon strips across the top and bake in a moderate 375 F oven until done — about 1 1/4 hours.

Pear garnish

Place canned pear halves cut side up in a baking dish; add a small amount of syrup from the can. Fill pear cavities with cream cheese and bake about 15 to 20 minuets. Garnish with mint jelly and maraschino cherries and serve with meatloaf.

Notes: Mrs. Day reccommends making a ditch in the meat around the edge of the baking dish before transferring to the oven. This will allow the juices to pool. Let stand for 20 minutes before serving in order for the juices to be absorbed back into the loaf.

It was a special-occasion dish that embodied several of the home-cooking trends of the 1930s, when the Great Depression loomed large over Canadian households.

“There was a lot of pressure on women to sort of pick up the slack and find ways to take care of the family, even when budgets were tighter,” says Rebecca Beausaert, an adjunct professor of history at the University of Guelph. “So they had to become pretty inventive with their dishes and do a lot of substituting.”

Canned and pre-packaged ingredients melded with scratch cooking, and store-bought bread was a staple for those unwilling to risk the cost of ruining homemade dough. Electric appliances were becoming the norm and food nutrition was top-of-mind.

At the same time, women were encouraged to think of homemaking as a profession as well as an academic pursuit.

“Women were to remain domestic, in the home, and to be good cooks, good mothers, good wives and good nurturers,” Beausaert says. “So these figures existed that women were supposed to look up to and mimic to help keep society stable — and in the 1930s that would have been even more important in the midst of so much economic and social upheaval.”

These figures existed that women were supposed to look up to and mimic to help keep society stable — and in the 1930s that would have been even more important in the midst of so much economic and social upheaval.”–oriRebecca Beausaert

For nearly a decade, Mrs. Madeline Day was that figure for Winnipeg women.

From 1935 to 1939, she published a regular column in the Winnipeg Free Press and invited housewives to weekly seminars at her test kitchen on the fourth floor of the paper’s former Carlton Street headquarters. The annual cooking school was her signature event.

Day’s first visit to the city, however, happened in 1933 during a similar conference hosted by the Winnipeg Tribune.

At the time, she was a travelling lecturer with the DeBoth Homemakers’ School — an institution founded in New York and Chicago by American home economist Jessie Marie DeBoth, whose goal was to elevate home cooking through science and dramatization.

DeBoth also appears to have been something of a feminist. In a cookbook published in 1929, she writes about the importance of so-called “women’s work” and notes that the U.S. census had finally conceded to listing housewives as homemakers instead of as unemployed. “This is real progress,” she wrote.

If DeBoth didn’t invent the public cooking-school format, she certainly popularized it. The events spread like wildfire through the States and into Canada, spurred on by the marketing opportunity they presented.

She partnered with local newspapers — which would promote the affairs through a flurry of articles and ads targeted to female readers — and peppered her cooking lessons with testimonials about specific products.

The schools would always conclude with a fashion show hosted by a local dress shop, as well as a generous prize giveaway sponsored by a department store.

Attendees were promised modern recipes to make life easier and husbands happier. Advertisers were given a captive audience.

“In the early 20th century, a lot of companies started to recognize the importance of the female consumer,” Beausaert says. “Women are still largely the ones shopping for their families, shopping for food, shopping for furnishings, so I think a lot of companies saw that they were a bit of an untapped market.”

It was the same story in Winnipeg. Prior to her local residency, Day spent years hosting DeBoth-branded cooking schools in places such as Los Angeles, Atlanta, Honolulu and Saskatoon. She seems to have co-opted the marketing methods when she started her own school in Canada and the Winnipeg Free Press was more than happy to jump on the trend.

Day’s writing often landed in the women’s section of the paper, next to personal columns and advertisements for flour, appliances, vitamins and makeup. More often, her face and name were used to endorse said advertisements.

At the Free Press Cooking and Homemaking School, the stage was set with furniture, china, silverware and crystal from Birks-Dingwalls and the electric kitchen equipment was supplied by Winnipeg Hydro. Even the live canary was sponsored by a company called Brock’s Bird Seed and Treat.

In today’s world, Day would be a social media influencer — someone selling an idealized version of reality along with all the gizmos and gadgets required for self-actualization. She was simultaneously relatable and aspirational.

Reality, however, couldn’t have been further from the truth.

Day was born in rural Illinois and grew up in a suburb of Chicago. Based on genealogical records, she was the oldest of three siblings and left home in her early 20s to attend university at La Sorbonne in Paris.

It’s unclear what she studied, but letters home to her parents — written in tight, illegible cursive — mention Italian language classes, and a blurb in the Chicago Tribune notes that she graduated with honours.

How she became a rising star in the homemaking world and ended up in Winnipeg is equally muddy.

There’s no record of her attending culinary school or working as a home economist before joining DeBoth’s, although she did have an uncle, John R. Thompson, who became a prominent Chicago restaurateur after starting a chain of “one-arm” self-service cafeterias (so-named for the school desk-style tables customers ate at).

Day returned stateside around the start of the First World War and married her husband, Robert Day, in 1916, giving birth to her only daughter, Rosemary, a year later in Montana.

The marriage was an unhappy and potentially abusive one, according to Day’s grandchildren, and the couple divorced some time after 1930. Madeline never remarried, but she kept her ex-husband’s name and the missus honorific.

She returned to Chicago and left her daughter in the care of her parents while travelling the continent as a DeBoth lecturer.

“Rosemary was raised by her grandparents, essentially,” Day’s granddaughter Nancy O’Brien says over the phone from her home in Florida.

Day died before O’Brien and her sister, Ann Bradley, were born. As a result, the women know little about their maternal grandmother.

“I didn’t know about any of the particulars, other than that she had a cooking school and that her daughter loved her very much and missed her,” O’Brien says. “They would correspond and every once in a while she came back to Chicago to visit her daughter.”

“She just idolized her mother,” Bradley says of Rosemary. “She didn’t like her grandmother, who she was living with, so her mom was kind of that romantic hero who would come visit.”

Until the Free Press reached out over Facebook, the sisters had no idea their grandmother was a highly regarded homemaking and cooking instructor with a loyal following north of the border.

“Gosh, she was divorced, she didn’t raise her daughter… and then she’s teaching these classes about being a good wife and a homemaker,” Bradley says. “I thought that was interesting, at least. I’m not really sure how she qualified for that.”

”Gosh, she was divorced, she didn’t raise her daughter… and then she’s teaching these classes about being a good wife and a homemaker.”–Ann Bradley

Still, even at a distance, Day’s daughter seems to have inherited her knack for cooking. Rosemary, who died in 2013 at the age of 96, was a proud home cook who specialized in standard Midwestern cuisine and exchanged recipes with friends. On one occasion, she even had a recipe published in the local newspaper, the Kansas City Star.

“She was a good cook and so I think she was flattered that they wanted to use one of hers,” says Bradley, adding that she can’t recall what the dish was. The clipping has been lost to time, buried somewhere in the family records.

After Winnipeg, Day took her cooking school to British Columbia and published in the Vancouver Sun. She returned to Illinois after being diagnosed with cancer and died in 1945 at the age of 54.

”It’s endless the amount of things you can learn about history beyond just the recipes.”–Rebecca Beausaert

Day’s real life may not have been as prim and shiny as the one she presented to the world, but her work offers a rare account of domestic life in North America during the 1930s. Her printed responses to reader questions highlight the concerns of the day and her recipes capture the tastes and trends of a generation.

“In addition to certain original creations,” Day said, when asked from where she draws culinary inspiration, “many of my best recipes have been given to me by women who attend my cooking schools elsewhere. During and after each school, I receive numerous suggestions for new dishes, many women suggesting their own favourites.”

Prof. Beausaret from the University of Guelph specializes in food history and leads a project documenting and digitizing the school’s large cookbook collection. She tells students that “cookbooks are textbooks in disguise.”

“The ingredients, the imagery in the cookbooks, how they’re constructed, who’s contributing, tell us so much about politics and economics and gender, race, ethnicity, religion, immigration, health and wellness,” she says. “It’s endless the amount of things you can learn about history beyond just the recipes.”

As is the case with the life and legacy of Mrs. Madeline Day, food is just the entry point. What’s happening beyond the kitchen is often more interesting.

eva.wasney@freepress.mb.ca | Twitter: @evawasney

Share your recipes with the Free Press

In celebration of the paper’s 150th anniversary, the Winnipeg Free Press is collecting recipes to be published in a community cookbook, entitled Homemade, later this year.

Visit winnipegfreepress.com/homemade to learn more about the project and submit your own recipe. Each submission will be entered into a draw to win copies of the cookbook, Free Press swag and other prizes.

Dishes can be cherished family favourites or everyday staples — just make sure to tell us the story behind the recipe.

Join our Facebook group for discussions, recipe swapping and event updates.

Eva Wasney has been a reporter with the Free Press Arts & Life department since 2019. Read more about Eva.

Every piece of reporting Eva produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Saturday, January 22, 2022 10:09 AM CST: Adds link

.jpg?w=100)