Downtown destination Eaton’s department store was a one-stop shop, a social hub and an architectural gem

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 21/12/2021 (1137 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

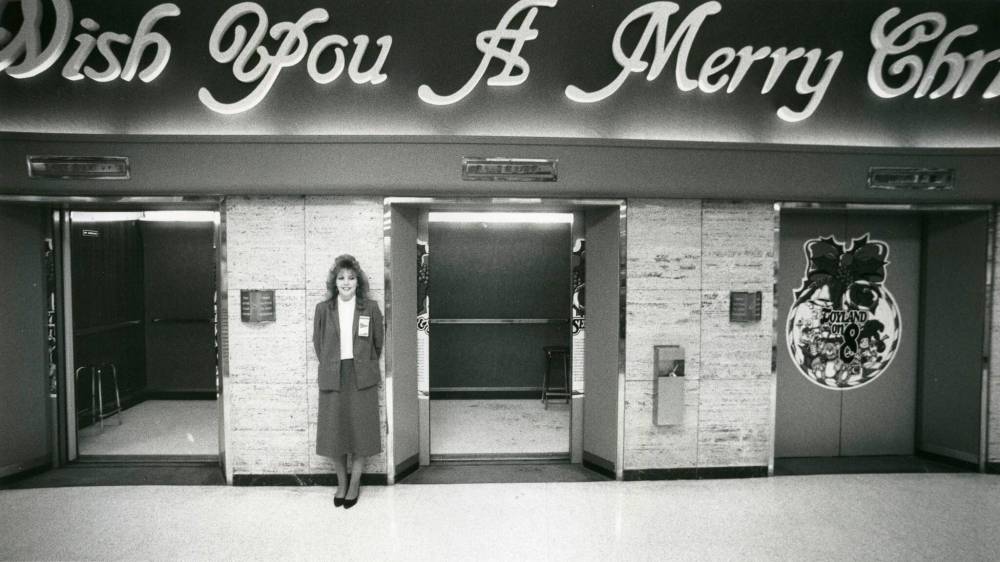

This month’s Landmarks looks at a ghost of Christmas past. The Eaton’s department store on Portage Avenue no longer exists as a bricks-and-mortar building, but it lives on in many Winnipeggers’ hearts and minds, especially at this time of year.

With its annual Santa Claus parade, elaborate Christmas windows and seasonally expanded Toyland, Eaton’s was a December destination.

During the rest of the year, the over-700,000 square-foot structure was an integral part of many Winnipeggers’ routines. My grandmother took the bus to Eaton’s every Thursday as the weekly treat in her round of household chores. The store seemingly sold everything — furniture, fashion, food, hardware, books, pets, musical instruments, even “notions” (an intriguing bit of signage that lasted into the 1980s).

The store was a social centre. Before the days of cellphones, friends would arrange to rendezvous at the statue of Timothy Eaton on the first floor. In its heyday, it was an economic anchor for the city centre, and its massive mail-order operation underlined Winnipeg’s status as the shipping hub for the Canadian west.

The Eaton’s building was also an understated architectural gem — flexible, muscular and very modern. Designed by Winnipeg architect John Woodman and built in 1905, it stood as a red-brick harbinger of the coming century.

According to Dr. Oliver Botar, a professor of art history at the University of Manitoba’s School of Art who was part of the Save the Eaton’s Building Coalition in 2001, the structure “was important both from the point of view of its architecture and from the point of view of the streetscape and its place in the urban fabric of Winnipeg.”

In our age of over-consumption, it might sound odd to talk about the liberating effects of shopping, but in fact the vast and magnificent department stores of the 19th century, starting with Paris’s Le Bon Marché in 1852, and including Harrods in London and Marshall Field’s in Chicago, helped to usher in a new era of modernity and social mobility.

Before that, shopping was mostly a dreary chore at small, dark shops where goods were kept behind a counter. The department store made shopping into a form of recreation, and a luxurious one at that, with these palaces of commerce offering comfortable reading and writing rooms, restaurants with live orchestras, even childcare, along with big events and spectacles.

Department stores kick-started the modern dynamic of display and desire, with large, well-lit ground-floor windows beckoning shoppers in. Once inside, customers — or “guests,” as canny retail magnate Henry Selfridge liked to call them — would find a range of goods, presented in expansive, attractive, wide-aisled floors. The department store’s unprecedented amount of accessible, affordable ready-made products went hand in hand with the rise of the urban middle class.

There’s even an unexpected feminist angle to this social history. At a time when middle- and upper-class women were not welcome in public spaces, when it would be considered scandalous for a “respectable” woman to stroll on city streets unescorted or dine alone at a restaurant, early department stores offered a refuge for women to move about unhampered.

Emile Zola’s 1883 novel about a fictional Paris store was titled The Ladies’ Paradise (Au Bonheur des Dames), while Edward Filene referred to his Boston department store as “an Adam-less Eden.”

As the first Eaton’s to open outside Toronto, the Portage Avenue store marked Winnipeg as a thoroughly modern metropolis and immediately became a beacon of civic pride.

Russ Gourluck’s A Store Like No Other: Eaton’s of Winnipeg, a fascinating, informative and deeply affectionate account of “the Big Store,” as many Winnipeggers called it, demonstrates how Eaton’s was enmeshed in city life, from setting up a flood relief centre in 1950 to offering overnight refuge for shoppers and downtown workers stranded by the 1966 blizzard. (Gourluck also includes a recipe for the Grill Room’s asparagus cheese rolls!)

For Botar, the store was crucial to Winnipeg’s 20th-century urban design.

“The Eaton’s department store shifted the centre of gravity from Main Street to Portage,” he says. “The sheer scale of that building really identified Winnipeg, and Portage Avenue, as a major Canadian urban centre. And then there was the catalogue building built onto the back, which is still there as Cityplace.

“The Eaton’s department store shifted the centre of gravity from Main Street to Portage.” – Dr. Oliver Botar, professor of art history

“The whole complex was so important, a key element not only of the economy of the downtown, but also the streetscape.”

The store’s mail-order and catalogue building — Heritage Winnipeg calls it “the ancestor of Amazon” — would send out everything from a single spool of thread to entire houses, prefabricated and delivered by boxcar.

The Eaton’s complex “was key to first of all defining Winnipeg not only as the distribution centre for western Canada but the retail centre of western Canada,” says Botar. “Plus, the Eaton’s catalogue really helped give the art community here its start.”

Brigdens, a local commercial art firm, had the standing contract to do the drawings for the catalogue, or “the wishing book,” as it was sometimes called, and it employed such artists as Alison Newton, Pauline Boutal and Charles Comfort, Botar relates. It was especially important that “Brigdens employed women who otherwise wouldn’t have had a chance to earn money as artists,” he states.

“Just from the point of view of the economic and artistic history of Winnipeg and the image of Winnipeg as its peak, the Eaton’s building was one of the most important monuments to that.”

Winnipeg in the early 20th century was sometimes called “the Chicago of the North,” and Woodman’s design references what is called the Chicago School of architecture. Instead of relying on thick, load-bearing masonry walls, which only allow for small openings, the Eaton’s building started with a structural steel frame, which meant that the exterior walls could be broken up by big bands of plate-glass windows.

Its exterior revealed, in a forthright way, a dynamic balance of vertical and horizontal energy. Woodman, who also designed the original Free Press building on Carlton Street and the Paris Building on Portage, dispensed with the decorative elements seen on most important buildings of the time — columns, capitals, pilasters, tracery — instead creating a spare, clear and robust fusion of form and function.

“From the point of view of its simplicity, the large Chicago-style windows, the lack of ornamentation, it was proto-modernist,” says Botar. “That was one of the principal aspects of its importance for Winnipeg but also for Canada.”

As Gourluck relates in his book, Eaton’s also showed off many new technologies, including escalators, elevators, a state-of-the-art sprinkler system and hot-air blowers at the entrances offering a (literally) warm welcome to winter-weary Winnipeggers.

This modernity, which must have seemed so revolutionary in 1905, might have brought about the structure’s downfall almost a century later.

This modernity, which must have seemed so revolutionary in 1905, might have brought about the structure’s downfall almost a century later. By 2001, the collapse of the Eaton empire and the consumer shift toward suburban malls, combined with a push for a new downtown arena, meant the building was in peril.

Despite the committed efforts of activists, artists, urbanists and architecture fans, it was hard to rally public opinion and sway political forces to get Eaton’s designated as a protected heritage building.

Botar compares Eaton’s with the Hudson’s Bay store down the street, which was actually built later but harks back to the highly decorated historical styles of the 19th century. “(The Bay) is more like what people think a heritage building should look like,” he suggests.

“People often think ornament is what’s make architecture, and (Eaton’s) was unornamented. But in fact, that was exactly what made that building so important at the national scale.”

The Eaton’s building was demolished in 2003, but memories of this significant downtown landmark still stand.

alison.gillmor@freepress.mb.ca

Alison Gillmor

Writer

Studying at the University of Winnipeg and later Toronto’s York University, Alison Gillmor planned to become an art historian. She ended up catching the journalism bug when she started as visual arts reviewer at the Winnipeg Free Press in 1992.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.