‘We are on our last legs’ Chronic shortage leaves one in five Winnipeg ER and critical-care nursing positions vacant

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 30/11/2021 (1564 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

A chronic shortage of emergency and critical-care nurses in Winnipeg has left those working exhausted, frustrated and, in some cases, ready to abandon the profession.

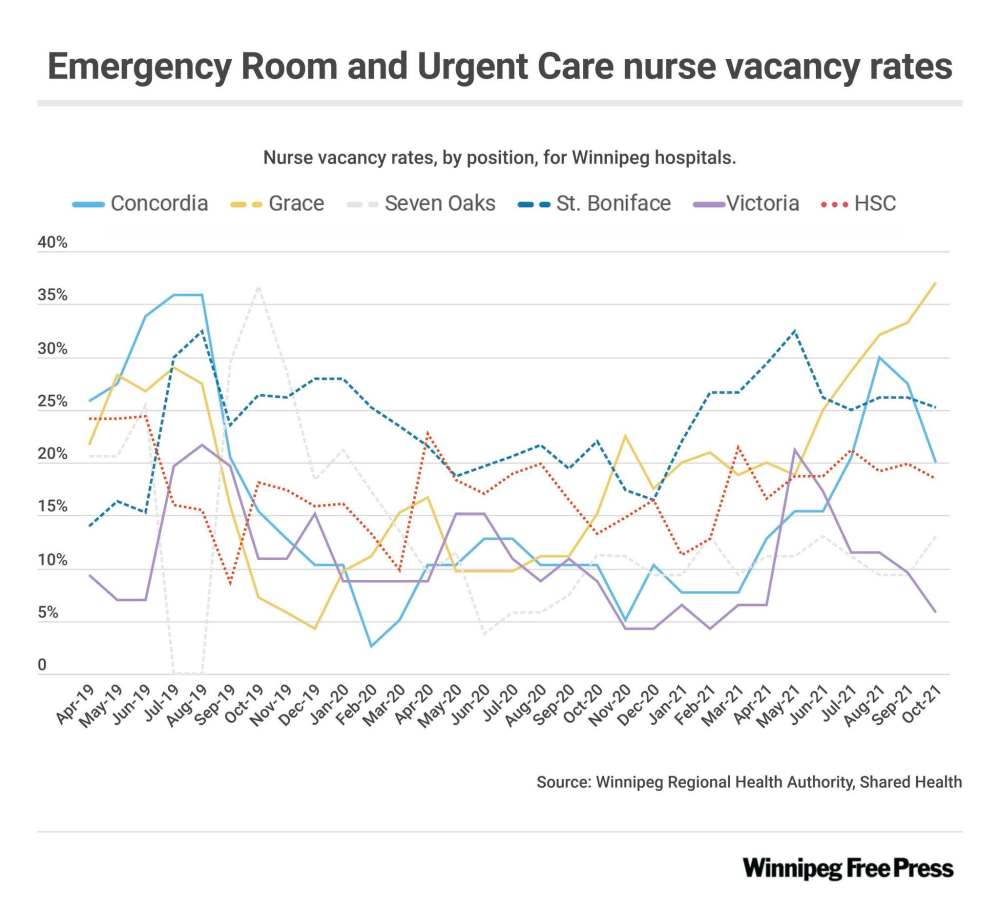

More than one in five of those positions — 22.7 per cent — in city facilities was vacant in October, recent data shows.

And the situation is even more alarming at Grace Hospital’s emergency department — one of only three in the city — where the percentage reached 37.1 in October, data provided to the Free Press by the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority and Shared Health revealed.

St. Boniface Hospital’s intensive-care unit’s nurse vacancy rate teetered just above 30 per cent.

“This winter, there is no reserve left,” said one St. B critical-care nurse. “We are on our last legs. It will take very little to push more nurses out of the profession.”

And while the current COVID-19 fourth wave is straining resources and threatening to further unravel the situation, vacancies have been an issue for some time. The stats show only a marginal increase in the proportion of unfilled nursing positions since October 2019 — when hospital-wide openings were at 18.04 per cent compared with the 18.27 per cent logged in October 2021.

The vacancy rates are the only measure of data the WRHA and Shared Health use to track unfilled positions and new hires, but they don’t reflect the cumulative toll the past 20 months have taken on the people working, said nurses who spoke to the Free Press on the condition of anonymity.

“I can’t even explain how crushed we are right now,” said the St. Boniface critical-care nurse, who described the effects of nearly two years of constant uncertainty during the pandemic, combined with perceived disrespect from both leadership and management.

“Even if they fully staffed us, the sick calls and the stress is killing us.”

Most have been forced to work with little relief throughout the course of the pandemic. There have been some new hires, but their lack of advanced training limits the work they can take on and the types of patients they can provide care for; there are still fewer experienced nurses to look after the sickest patients.

Nurses described the current staffing crisis in terms that mirrored the experiences many detailed during the chaos of the pandemic’s first and second waves. It’s still happening, but they’re even more exhausted now.

In mid-November, the province announced a plan to recruit third- and fourth-year nursing students to fill gaps in surgical and medicine units, working under mentors. Nurses from other departments have already been added, but they can’t replace years of experience.

A Winnipeg emergency nurse said the situation is not improving. They still have to close ER beds due to lack of staff on a regular basis ― at least a couple of times a week. And there is still a consistent backlog of admitted patients waiting on stretchers in ER corridors for hours, or even days, because there are no beds available for them in the wards.

“Essentially there’s no flow,” the nurse said. “It’s not getting better.

She said filling positions with inexperienced nurses and students doesn’t do much to help, and the current reality is “wearing on people.”

“They might say, ‘Oh, we’re filling spots, we’re hiring people.’ But if these people aren’t trained, then it might look good numbers-wise, but safety-wise, it’s still not good. To be a good ER nurse, you need to have at least two or three years under your belt.”

New hires can’t work in high-acuity areas of the ER, so experienced nurses are still being asked to work when they’re scheduled to be off, and they are suffering.

“I think in the past, nurses would take pity and say OK, but… they can’t anymore, they’re burning out so badly,” the ER nurse said. “They’re always giving, and still people are, but they’re not willing as much anymore to work for the sake of the crumbling system.”

Manitoba Nurses Union President Darlene Jackson said she hears from concerned members daily that the number of nurses getting out of the system to take jobs with private companies or work in other provinces eclipses that of new hires or student postings.

“I’m not sure how many more nurses we’re going to be able to lose out of the system until we’re to the point where there are facilities that aren’t going to function anymore,” Jackson said.

Vacancy rates are worse in rural areas of the province, between 25 and 27 per cent in the Southern Health region and 27 to 30 per cent in the Northern region, she said.

The province could have prevented the situation from deteriorating further if officials focused on keeping experienced nurses; recruitment is important but retention is crucial right now, she said.

“These employers have ― I’m not going to say missed the boat… this is a big ship and it’s going to take a long time to turn it around ― but I think if they had actually stood up and taken notice about a year ago or a year-and-a-half ago, as we saw nurses leaving the system, as we saw our vacancies growing, and as we saw nurses going off on medical leave with the stress through the pandemic, I think if they had actually taken some really direct action at that point, really looked hard at how do you keep a nurse in the system… we may not be in this position,” Jackson said.

The best thing to do now is listen to front-line nurses, she said.

At the legislature Tuesday, the NDP continued to hammer the Tory government about the shortage. The Opposition obtained past vacancy-rate data from Winnipeg hospitals and rural health regions and tabled the documents last week.

When Health Minister Audrey Gordon was asked about the vacancies last week, she called on nurses to “stick with us.”

“Our front-line health-care workers are feeling what they call COVID fatigue,” Gordon told reporters. “Individuals have been at this, fighting the pandemic now for 19, headed for 20 months, so individuals are looking at other opportunities.

“But what we’re saying to them is, ‘stick with us,’ we are going to all get through this together. This is a very difficult time for the entire province.”

― With files from Danielle Da Silva

katie.may@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @thatkatiemay

Katie May is a multimedia producer for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.