A champion for women’s health Feminist clinic marks 40 years as struggle for medical rights, equality continues and evolves

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 08/10/2021 (1522 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In September, Texas passed the most restrictive abortion law in America.

It bans abortions after six weeks, a point at which many women don’t know they are pregnant. It’s a preview of what America would look like if Roe v. Wade was struck down, a chilling reminder that these hard-won reproductive rights could be eroded at any time. (The law was temporarily blocked this week by a federal judge.)

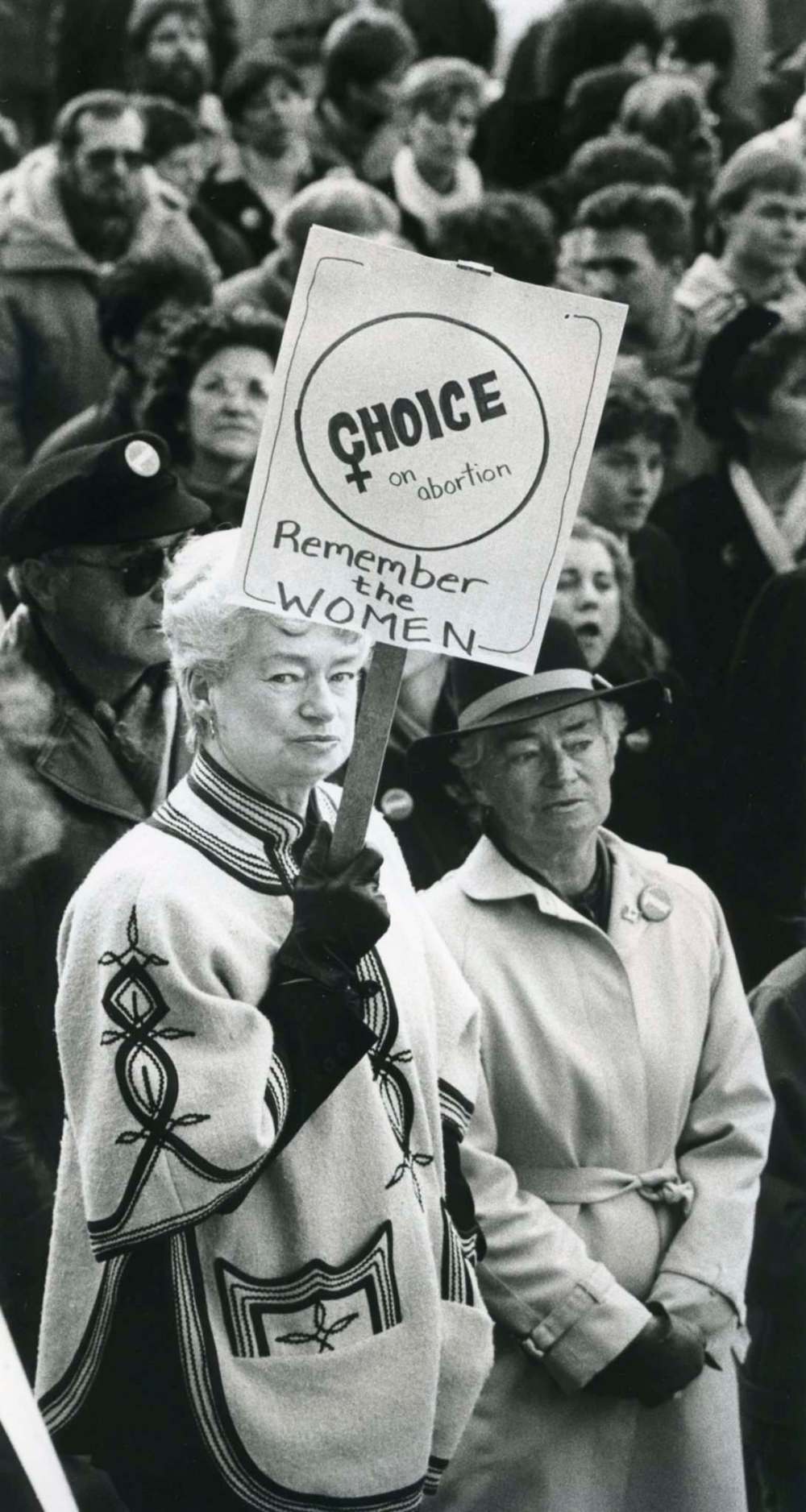

Last week, a rally for reproductive justice assembled at the Manitoba Legislature here in Winnipeg, to both speak out against the regressive law passed south of the border as well as ensure that nothing like that ever happens here. One woman raised a sign that read: “my arms are tired from holding up the same f—ing sign since 1970.”

These renewed conversations about reproductive rights echo the ones that were taking place in the early 1980s when abortion was a crime in Canada — conversations that led to activism and action and, eventually, to a small, feminist, pro-choice clinic in the centre of Canada called Women’s Health Clinic.

Since it opened in 1981, the clinic has been at the forefront of the battle for access: to abortion, yes, but also to birth control, to mental health services, to non-judgmental pregnancy support and counselling, to a place to give birth that isn’t a hospital.

“It’s interesting to be part of a clinic that, if I am pregnant, and I walk in the door, it doesn’t matter what I want to do: I can get that service within that place, right within that organization,” says Kara Nacci, a nurse in the abortion program at WHC. “So if I want to continue the pregnancy, there’s somewhere I can deliver. If I don’t want to continue the pregnancy, there’s somewhere I can handle that. It’s a really neat concept and it’s pretty unique as well.”

The clinic’s very existence is a testament to the work of women. The activists, the practitioners, the volunteers — all of the champions who saw a need in our community and made it happen.

In celebration of its 40th anniversary, here is an oral history of Women’s Health Clinic, as told by some of the people who shaped its formative years and those who are leading it into the future.

Founding: The fight for access

The Women’s Health Clinic opened to the public on May 4, 1981 in a small office space next to Klinic Community Health Centre on Broadway. It was an expansion of the grassroots, feminist, pro-choice programming offered through Pregnancy Information Services, which was founded by a group of volunteers in 1973.

In need of more space to accommodate growing demand for services, the WHC moved into its current home at 419 Graham Ave. in 1987.

● Ellen Kruger, founding board chair (1981): I worked at Klinic at the time… and Klinic had housed Pregnancy Information Services, which was a volunteer feminist service set up because people couldn’t access information about where to get birth control and information about abortion.

By ’79 or ’80 we were really having trouble keeping up with the number of women coming in needing birth control education and unplanned pregnancy information.

Klinic hired a doctor on fee-for-service (basis), who would really work for Pregnancy Information Services two nights a week. He’d see the young women around birth control, pregnancy, abortion referral, which was very difficult to get at that time.

● Dr. Carol Scurfield, medical director of WHC (1983 to present): Getting access to abortions in Winnipeg meant that there had to be approval by the hospital and physicians. So we would have to write a letter to say that her health and life were in danger. She couldn’t just want one and get one.

We were happy to do it because otherwise there wasn’t access, but it really was a barrier and an immense cost, both emotionally and financially.

● Kruger: It became apparent that… Pregnancy Information Services needed its own clinic. So we had to brainstorm, how do we get this off the ground? Get funding for staff? We can bill fee-for-service if the government’s not interested — which they weren’t — so we can get a doctor, but we need other staff.

The federal government had what we called “make-work” grants and so we got a grant and then Linda, who’s a pre-eminent fundraiser, agreed to be our fundraiser.

● Linda Taylor, founding board member and former chair (1981 to 1984): I think we developed around $40,000 almost right away, just from individual people going door-to-door.

This was a time when the women’s movement was quite strong and there was a lot of feeling in the community that things had to change around women’s health.

There was some pushback, legitimately, from some women in the community who said, “This is a health-care service. Why are we having to contribute to this? This should be covered off by universal health care” — which, of course, we agreed with. But on the other hand, we were making inroads in new areas, so we had to get started somehow.

In 1981, Howard Pawley became (NDP) premier, prior to that it was (Progressive Conservative) Sterling Lyon, who was not at all interested in women’s health. Pawley was not only elected, but there were the first NDP women (MLAs) ever elected — five of them — and they were all very supportive. And so they were able to make inroads inside the government to assist us in the development of the clinic. So it really was the political strength of the left wing. It was the strength of the women’s movement and I think a strong and legitimizing board, which all happened to come together at the right time.

Abortion: Unfettered and on-demand

Abortion was a crime in Canada until 1969, when then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau amended the Criminal Code to allow doctors to perform abortions in hospitals if a pregnancy was life-threatening — though hospitals were not required to offer abortions.

Prior to this amendment, a doctor providing abortions could be face life in prison and the person receiving an abortion could be jailed for up to two years.

● Taylor: Our overall goal, without question, was to allow women to have abortions in community-based facilities, which offered non-judgmental and free services to any woman who needed it. That’s what drew the whole group of us together.

And I’m partly responsible, as chair, but we ended up believing that if that was what we fought for in a very clear and public way, we might end up losing all of our support, all of our financial support. So we kind of ducked the issue for about 10 years, I’d say.

● Kruger: But we always provided referrals for abortions. We had the connections — a lot of people had to be referred to Grand Forks in those years previous to Women’s Health Clinic. After Henry (Morgentaler) came to Winnipeg, we could refer to him; but not always because there was that whole fight with the clinic being shut down.

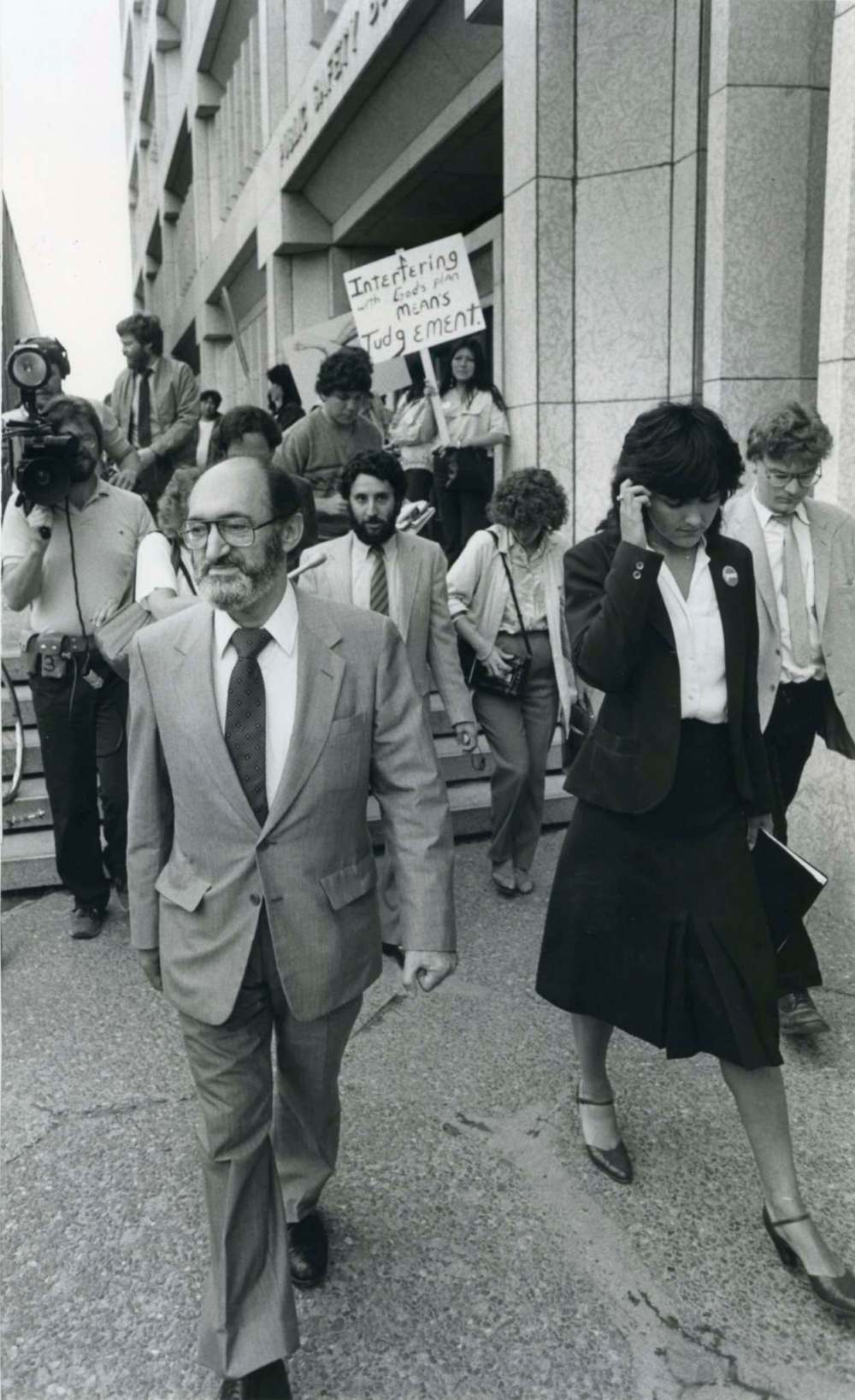

Dr. Henry Morgentaler, an outspoken advocate for women’s reproductive rights, began providing unauthorized abortions in his Montreal clinic in the 1960s. By 1973, he claimed to have performed 5,000 abortions and was arrested and charged under the Criminal Code. He spent 10 months in jail and was later acquitted. In 1983, he opened a (still-illegal) abortion clinic in Winnipeg on Corydon Avenue. It was raided four times in the months and years after its opening. Morgentaler died in 2013.

● Kruger, who had left the WHC board and was chair of the Coalition for Reproductive Choice in 1983: We had a demonstration going every week because they raided every week. Hundreds of people would come (to the legislature).

We said no demonstrations at the Morgentaler Clinic, we didn’t want women to have to run a gauntlet. And then the anti-choice people started demonstrating there and women came from the community that weren’t even part of the organizafation and demanded that these people stop demonstrating there. People were fed up with the way women were treated around reproductive health.

● Dr. Suzanne Newman, former medical director of Jane’s Clinic (formerly the Morgentaler Clinic); physician provider of abortion services at WHC (2007 to present): I started working at the Morgentaler Clinic before I became a doctor. I started there in 1983, six weeks after he did his first abortion there — so during all the protests, and all the insane people who were picketing the place.

Winnipeg was the first place that (Morgentaler) came after Quebec. And the reason he chose Manitoba was because of the NDP government at that time, which was nominally pro-choice, and he thought this would be a good way to ease into challenging the law because, at that time, abortions in clinics were illegal. So he opened here in my neighbourhood, a five-minute walk from my house, on Corydon Avenue in probably April ‘83. He made no bones about it — he said he was going to do that and he did abortions for about six weeks before he actually had a press conference and opened the door. And during that six-week period there were protesters constantly — noisy people with terrible signs, which invoked things that they had no right to invoke, like Holocaust signs and stuff life that.

I was walking with a neighbour who was a Catholic Irishman, and two of my kids, and one of his kids — for an ice cream or a Popsicle or something down the street — and passed that by, and I just saw red. I just could not stand to see those signs.

I hadn’t really thought much about the issue before because, to me, it was a non-issue — like yeah, of course, who is going to make that decision for somebody else? But at that moment, when I saw all those ugly faces — and they were ugly, they were distorted with rage and anger — I grabbed my poor kids and walked up the steps and argued with those protesters.

In May of ‘83, I became involved as a volunteer to do whatever it was I could and then I joined what was called then the Coalition for Reproductive Choice. I was involved in two of the four police raids as a volunteer. And that’s where I became politicized.

Newman’s work as a volunteer drove her decision to become a doctor at 41.

● Newman: There was an editor at Herizons magazine who was exactly 10 years younger than me. I was 38, she was 28. We knew each other a little bit socially. She had four kids, I had four kids. She had Grade 11. I had university. I was there because I was handing in some article that I was supposed to write for her, and she said to me, “I’m going to go back to school and be a doctor because that’s what this world needs.” And I was pumping her up and saying, “Yes! That’s what we need, we need doctors like you.”

I rode my bike home and, by the time I got home from River and Osborne, which was about two or three kilometres from my house, I thought, “F—, I’m gonna be a doctor, too.”

● Kara Nacci, nurse, abortion program at WHC (2007 to present): My mom had a job as the administrator at the Morgentaler Clinic. I was about 14 and she’d haul me off to these marches, or I would sit in the kitchen at the clinic and eat digestive cookies and drink apple juice while I did my homework, waiting for her to finish work. I just kind of grew up with all of that kind of in the background, like, this is just perfectly normal. Like, why all the fuss? But also watching the work that they put in, like meeting women down the street and giving them headphones and sunglasses and a volunteer on either side to escort them through protesters so they could get their abortion while people are hollering terrible things at them.

● Newman: We used to take pictures of protesters outside, so that we would be able to recognize them and we had them on our wall.

One time, one of those women needed an abortion.

She came to the back door when we were closed, we weren’t even doing abortions at that time. And that was the time we were driving them — or some of us were driving them — to Grand Forks for abortions, and she stands out in my mind quite a bit because she didn’t change her tune after I brought her back. I was with her, holding her hand during her abortion. We had the day together. But she was back out picketing us afterwards.

“I was with her, holding her hand during her abortion. We had the day together. But she was back out picketing us afterwards.” – Dr. Suzanne Newman

It was OK for her because she was in a situation that required it, but it wasn’t OK for everybody else — like that kind of story. And how we delude ourselves into thinking we’re special or we’re different. In our experience, and Kara’s and my experience over all these years, 35 years or more, however many years. Women of every possible background have required abortions: doctors, lawyers, ministers. Any religion, any political persuasion. Most are mothers.

On Jan. 28, 1988, the Supreme Court of Canada struck down Canada’s abortion law as unconstitutional under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, thereby decriminalizing the procedure.

● Kruger: I remember the night… because I got to celebrate the 1988 decision with the (reproductive choice activists) in Toronto on my way to meet Linda in the Caribbean (for a vacation) and there was a big party and Henry was there with his latest partner and their new baby… I just remember it being a big party.

● Scurfield: There wasn’t like a sudden dramatic change. The laws changed, but you needed to get people on board with those changes.

We’re still seeing changes and more medical practitioners are interested in providing abortion services. There was still fear on their behalf that something would happen to them — that happened with the shooting in Winnipeg.

Dr. Jack Fainman was the head of obstetrics and gynecology at Victoria Hospital in 1997, when he was shot by a suspected anti-abortion gunman through the window of his St. Vital home. In addition to delivering thousands of babies, he also performed therapeutic abortions for patients. Fainman died in 2014.

● Taylor: It was only in the ‘90s that Dr. Jack Fainman was shot. His partner was very involved with reproductive choice activism and he was not a huge provider, but he did, on occasion, provide abortions. Somebody walked down behind his house and shot him and he never practised medicine again.

There was a lot of viciousness going on around the community.

● Kruger: The anti-choice people started a centre called the Pregnancy Distress Centre. They were located down the street from Klinic and Women’s Health Clinic and they would lie to people. They would get young women in there… they would send them to doctors that would delay on pregnancy tests, they would do horrible things to people.

When the women who had gone there finally found their way to us… they couldn’t get an abortion here, they were going to have to go out of province. And that kind of shit is probably still going on.

In 2007, Jane’s Clinic (formerly the Morgentaler Clinic) abortion services were amalgamated into WHC’s medical program.

“When the women who had gone there finally found their way to us… they couldn’t get an abortion here, they were going to have to go out of province. And that kind of shit is probably still going on.” – Nurse Kara Nacci

● Newman: The reason that we amalgamated with Women’s Health Clinic — the sole reason that happened — was so women wouldn’t have to pay out of their pocket. So, with Henry, the government at that time — and through all those years — refused to pay for abortions done outside the hospital. And I spent hundreds if not a thousand or more hours lobbying face to face — individuals, ministers, the premier — everybody I could think of. Not just me. A whole coalition, everybody. There were so many people lobbying.

What (Morgentaler) said when I was so disappointed that we had to become under Women’s Health Clinic and be part of another program, he said to me, “What was the most important thing for you, Suzanne?” And I said for women to not have to pay. And he said, “You got that. So now you should be happy. And you shouldn’t have to worry about all these smaller things.” And so that is what I tried to take home with me.

● Nacci: Any time you take two organizations and try and squish them together, there’s gonna be some work to be done. And I think overall, it’s been OK. We have the Women’s Health Clinic name, which has always been well respected. When you Google “abortion Winnipeg,” Women’s Health Clinic comes up. And so we are now that resource for all women all across this province, and in other provinces, as well.

In 2015, the abortion pill Mifegymiso, a combination of the medications mifepristone and mifepristol, was approved for use in Canada. The pills are administered orally, and can be used to end a pregnancy up to nine weeks (this is called a medication abortion). Mifegymiso was supposed to revolutionize access to abortion for people in rural communities who would no longer necessarily have to travel to Winnipeg or Brandon to get a surgical abortion. But it hasn’t gone that way. It took until 2019 for the Manitoba government to approve universal access, and many communities still do not have trained physicians who offer it.

● Newman: I thought, too, that the pill would revolutionize everything. But it didn’t and why didn’t it? I think because doctors are just not wanting to go out on a limb. Abortion is still somewhat of a dirty word for many people and why bother if somebody else is doing it? Women’s Health Clinic is doing it, why should I have to do it? Why should I have to go to a conference or do a two-hour online course to learn if somebody else does it? And I think it is a stigma about abortion.

That’s why I am “out” about being a provider because I don’t want women who see us to feel stigmatized of having an abortion. I feel proud of what I do. And although women who come to us don’t have to feel proud of having an abortion, they should not feel shame or stigmatized.

I thought that all the family doctors would be right in there. And at first they didn’t do it because there was no remuneration for it. But now there is, so what else? It isn’t lack of education to me. It’s lack of interest and lack of wanting to put yourself out on a limb I think. And that’s a sad thing because we’re still struggling with the same abortion access worries that we always were.

● Nacci: I think the other piece of that is in those smaller communities, clients don’t necessarily want to access that particular type of health care there, right? Like, maybe their aunt works at the health centre. Fair enough. That’s their prerogative, for sure. But that shouldn’t stop the providers in those small communities from offering.

“One of the most profoundly satisfying pieces of being a doctor is providing this care.” – Dr. Suzanne Newman

● Newman: One of the most profoundly satisfying pieces of being a doctor is providing this care. And partly that’s because there aren’t a whole lot of people lining up to do this work. But I wish that more people felt like this, because it is profoundly satisfying on so many levels.… It’s good work that we do.

● Nacci: To have someone come to you and trust you with something that they wouldn’t tell their best friend or their mom or whatever and you know we may be the only people that they confide in and say I need your help and and then we can help them with that — whether it’s a difficult decision or a totally straightforward decision, it doesn’t really matter. They leave their appointment and almost every single person coming out of there is like, “Wow, that was not nearly as bad of an experience as I thought. Thank you so much, everybody here is so wonderful. Thank you, thank you, thank you.” It’s really rewarding.

Birth control: My body, my choice

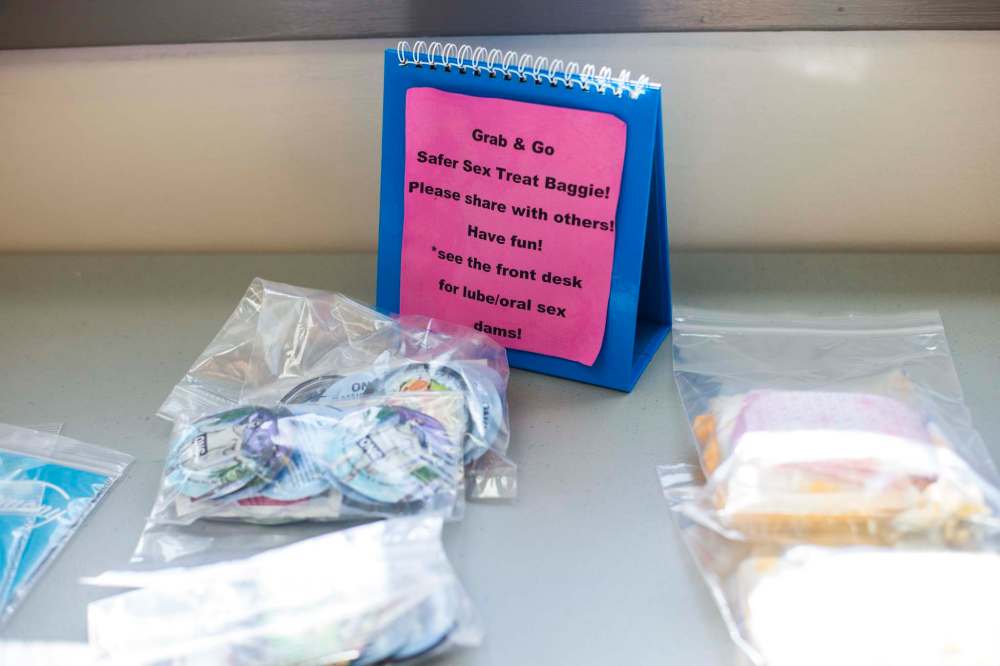

The Birth Control and Pregnancy Counselling Program has been a cornerstone of Women’s Health Clinic since it was established in 1985. Trained volunteers help people navigate everything from unplanned pregnancy to birth control options and safer sex practices. The goal was as it is today: to empower clients so they can make informed decisions about their reproductive health by offering non-judgmental, pro-choice and compassionate support.

● Gio Guzzi, team leader of the birth control and pregnancy counselling program at WHC (1986 to present): I actually started as a volunteer in the same program. I graduated with my education degree and I wasn’t ready to go into the school system, I wasn’t sure how I would be in systems. I love the educational part, and working with people, the creativity, that piece of it. I wanted to be somewhere where I could be feminist and all that. And then the person who had trained me was resigning and so things came into place, thinking, Oh, my God, I could use my education degree that’s not in an educational school setting. That would be part of working in groups and developing skills and increasing our capacity to understand the world around us and challenge all that thinking around health care and feminism. It was like the whole package deal.

● Kruger: (From the beginning) we were critically involved with birth control information. When you did a counselling session with a person there with an unplanned pregnancy, before she left that session you did birth control education. We don’t want you coming back with another unplanned pregnancy. You know people don’t necessarily come back once the crisis is over, so that education was critical.

● Taylor: It wasn’t only about providing support in terms of seeking abortions, it was also really about being able to control your own body.

● Kruger: There were only a couple of safe places in town, there was Mount Carmel, there was Klinic and Health Action. And then we knew which were the sympathetic doctors, but the public didn’t know which doctors would give young people birth control. So that was a big issue, getting non-judgmental birth control counselling to young women so they didn’t become pregnant.

● Guzzi: We kind of think of an interaction with a client as a site of information for whoever’s in their circle. So even if they’re not thinking right now of an IUD/IUS, they may in the future, so now they know what it’s about. For a lot of younger people, you tend to go to who’s around you, your friends, for sites of information; older siblings with some. Some of that’s changed, but not completely, right? We just never think you’re just passing on information in conversation with just the person you’re with. It goes back out into the world.

The biggest shift over the decades has been online information. You can get on to incredible websites that are reliable for getting information about sexual health, reproductive health. That’s great. But some people need the conversation, they need to just talk it out. So we can offer that. The use of hormonal methods of birth control have been around for a long time, and they work for some and not for others. So, here’s some permission to just talk through what your concerns and questions are. I mean, we’re not substitute labour, right? You’re still seeing a doctor, a nurse for the prescribing, the ultimate decision. We’re the first step of getting information and talking about how this fits into your life.

”The biggest shift over the decades has been online information. You can get on to incredible websites that are reliable for getting information about sexual health, reproductive health.” – Gio Guzzi

In the ‘80s, it was if you got the right pamphlet. Although there was incredible feminist literature created. Montreal Health Press, out of Montreal, was groundbreaking in North America. They put out handbooks called The Birth Control Handbook, The Sexual Assault Handbook, and it was written by feminist health activists.

The 2010s saw a marked rise in the popularity and demand for the intrauterine device (IUD), a small, T-shaped device that is inserted into the uterus to prevent pregnancy.

● Guzzi: IUD/IUS, that’s wild. Oh my God, if someone had said in the ‘80s, IUD/IUS, it’s like people had lived through really bad experiences hearing from their parents, or their aunties, or whatever — it wasn’t the best method, or they hadn’t figured out how to make it effective. Really, IUD/IUS, it’s working. They’re transformed, they’re better quality. And more people are open to it, because it’s a long-term reversible method.

● Scurfield: It wasn’t a popular choice because there were some concerns that were legitimate. But since the ‘80s they have become much safer and they developed a hormonal IUD, which has other benefits. We’re seeing a huge increase in the number of appointments; we probably put in 10 a year in the beginning and now we put in, like, 15 a week.

● Guzzi: Let’s be clear: that is not for everybody. The insertion of a device is not going to work for some people, and that’s both for an individual or culturally. There’s a whole different bunch of different reasons.

Other birth control methods have remained consistent over the past 40 years — in some ways, frustratingly so.

● Guzzi: You still have condoms, right? External condoms, male condoms. Internal condoms, or the female condoms — those are around, but they’re expensive. Barrier methods are not cheap, that’s the thing. Honestly, birth control and safer sex supplies, STI coverage — all these things need to be free.

● Scurfield: Why shouldn’t that be part of the program? It falls primarily on women to fund (birth control), when it’s really a population issue, not a women’s issue.

Birth Centre: Beyond the labour and delivery ward

The dawn of the new millennium brought the advent of publicly funded and regulated midwifery, which was incorporated into WHC’s medical program in 2001. Ten years later, the WHC opened the Birth Centre at 603 St. Mary’s Rd, the first of its kind in Manitoba, offering pregnant people alternatives to hospital birth.

● Scurfield: I was the chair of the council that brought the legislation… and got the first midwives working. That was huge. That was around 2000 and that brought a great opportunity for women to access different kinds of care.

● Madeline Boscoe, advocacy and program development co-ordinator at WHC (1990-2010): We looked first at midwifery, and wanting to get that done. At that point, there were lots of underground midwives being paid nothing, but no regulatory process. And the very first thing that happened is the Manitoba Advisory Committee did a report on legalizing midwifery, and publicly funding it. And it was the first sort of Manitoba document; we were a little late out of the gate. So, in 2000, there were 20 positions funded, finally. But then we went on and said, OK, so how are we going to expand it and support it? And we always saw a Birth Centre, that is a place for normal birth, as a component. We wanted to reclaim this idea of birth as a cultural event, that needed some medicalization, of course, but to reclaim it and by doing that, we reduce women’s anxiety — and by doing that, we reduce their pain management. A tense muscle is a hard muscle to breathe through.

Normal birth refers to labour and delivery that happens without medical interventions.

”We wanted to reclaim this idea of birth as a cultural event, that needed some medicalization, of course, but to reclaim it and by doing that, we reduce women’s anxiety– and by doing that, we reduce their pain management.” – Madeline Boscoe

● Beckie Wood, clinical midwifery specialist with Winnipeg Regional Health Authority (2000 to present) working out of the Birth Centre (2011 to present): There was a collection of us, maybe eight, who were practising prior to legislation, attending home births.

It was unsupported. The one thing that we know from the evidence is that hospital birth is safe within the context of an integrated health system… so prior to legislation, the transport (to hospital) and the consultations were not fluid, we didn’t have processes or procedures in place for any of that.

Manitoba was the first province to have a salary model of midwifery… and there was a lot of emphasis on integration with the health system.

● Scurfield: (The Birth Centre) was another tough argument with the government around birth not having to be in hospital all the time. That home births and birth in a birth centre… could be safe and was an option that women really wanted. And that was revolutionary at the time.

● Boscoe: We did a presentation to Theresa Oswald, who was the minister of health at that time (Note: Oswald would later serve as WHC’s executive director in 2017). And I think it mattered that it was a woman — she got it right away. And it wasn’t just a place for birth, we did want it to be in some ways, a centre of excellence for primary maternity care, so that other staff could come in and develop their skills and go elsewhere with them. Just like we do with the volunteer counsellors at Women’s Health Clinic, right? They’re everywhere. I’ve actually run into our volunteers here (in B.C.) who have become nurses and teachers. They’re everywhere, like little dandelions.

I think what Women’s Health Clinic tried to do was to model a different experience so women could reset their expectations. You know, working with a doctor or nurse or a counsellor, who wants to put you in the driver’s seat, and gives you information to make a choice and explain it to you means that once you’ve had that experience, you can go out into the world and go “oh, yeah, now I remember what normal is, that should be what I expect everywhere.”

The WHC manages intake, admissions and educational programs at the Birth Centre. All 31 midwives employed by the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority can provide birthing services at the centre. In the last year, roughly 1,300 people have requested midwifery care through the program and 296 babies have been delivered at the centre.

● Wood: It really truly is a centre of excellence for normal birth.

When you walk into a birth room here you do not feel like you have to be strapped to a bed. You feel like you should be walking around, moving, leaning on things. You feel a sense of freedom.

When you walk into the Birth Centre… the staff is friendly, supportive, encouraging, whether you’re walking in for a prenatal visit or walking in for labour; you feel like, “Oh, I’m meant to be here, everybody wants me here.” And then you’re admitted to a space and there’s a big family room where children and partners and parents can be present. We have a smudging room and there’s a garden. The sense of the natural world in and outside the building; those things all create the sense of, “My body is able, I’m meant to have a baby, I can give birth.” There’s a very strong sense of agency that comes through the physical space.

● Laurelle Harris, volunteer (1997 to present) and board chair (2015 to 2017): Having a birth centre and having the option of midwifery took all women, including racialized women and their families, out of systems that didn’t necessarily serve people very well.

If we offered this alternative, babies would be healthier, women would be healthier… and that might have an impact on dealing with the negative ways that hospital births have affected women of colour and Indigenous women.

● Boscoe: When we legalized midwifery, we put a scope of care requirement into their practices that wouldn’t be just first-come, first-through-the-gate, but some way people who were socially isolated on the margins would still be able to access these services — even though they didn’t put their name down before they got pregnant, which is what people do with daycare. We had to figure out a way of addressing equity in an equitable way. And that means putting time aside, and being intentional in intake. And that was true for the Birth Centre and for the midwifery practices.

This year represented another milestone for WHC; the Birth Centre turned 10 in 2021.

● Boscoe: It’s amazing, actually. It’s certainly for me one of the things that gives me a lot of joy, when you think of the hard work. You know, it’s funny — when I first took it on, they were kind of like “go and help midwifery and birth centre,” that was sort of the direction from the board. I went to see the woman who was in charge of legislation at Manitoba Health. And she said, “Madeline, it’s gonna take about 20 years all in.” I remember going home and thinking, oh, my God. And you know what? She was right, almost to the second. Reform movements take a generation, and that’s what it was.

Pregnancy and infant loss: Making room for grief

The Dragonfly Support Program offers group and individual counselling for people who have experienced a miscarriage, termination, pregnancy loss or the death of an infant. It received government funding in March 2021 and the first slate of sessions are currently underway. The goal is to offer peer support from volunteers who have gone through similar loss; as well as workshops on grief for other service providers.

● Erin Bockstael, team lead of the family and community programs (2010 to present): A lot of people would talk about their losses as part of their preparation for their (birth) or just as something that was affecting them as they were pregnant. We would reach out to people to get them into midwifery care or get them into a prenatal class and they would disclose the loss. There really wasn’t anywhere to send them for support other than general counselling.

Abortion and miscarriage are both very normal parts of life. But they are times where people might feel like these are experiences that can’t be spoken about.

(Now) we have somewhere for people to get support at every phase of their reproductive lives. You might be the same person that comes in for contraception or pregnancy counselling as a teenager and then you might be the person that comes in to have a midwifery supported birth or… decides to have and abortion and you might be somebody that experiences a loss.

(Elder Louise McKay) had been giving us teachings about dragonflies and how a dragonfly is born with everything they need and they go through different stages of life and grow into the experience at each stage… we found that it really connected to this program.

● Elder Wa Wa Tai Ikwe (Northern Lights Woman) of the Bear Clan, also known as Louise McKay (2020 to present): The teaching of the dragonfly has to do with new beginnings. It has to do with the person who you are meant to be is already who you are, but it may be buried inside. So having to find that strength or having to move forward because something is pushing you, it’s like that dragonfly nymph in the water looking up at that (lily pad) stalk and knowing it wants to get up there, it needs to get up there.

● Bockstael: We know that loss and grief doesn’t go away, but it becomes part of our lives. And sometimes we can build things around our grief that add meaning or honour those experiences.

More than reproductive health: a feminist approach to disordered eating

Women’s Health Clinic has been dismantling diet culture before “diet culture” was even in our lexicon. Now, in addition to the Provincial Eating Disorder and Recovery Program, WHC also offers resources and workshops for those struggling with everything from body image to how to build a peaceful relationship with food.

● Ann McConkey, dietician at WHC (1985-2000): Shortly after I started, a woman called Catrina Brown (author of Consuming Passions: Feminist Approaches to Weight Preoccupation and Eating Disorders) came to do some seminars and for the staff as part of her study in a way of thinking that she called self-perceived overweight, which was looking at weight as being not a big health issue. This was something brand new to me. I started sort of asking my clients different questions. And then it was like, oh, my goodness, wow, I hadn’t realized, as someone who had never dieted myself, the huge toll that dieting took. And so then I started becoming quite interested in this area.

The reason I was originally hired was because they were doing a lot of work in PMS (premenstrual syndrome) and they found a big nutrition component. And so they lobbied to get funding for a dietitian. So, at that point, most of my work was doing that, seeing women individually for all sorts of nutrition issues, but including PMS. I did a lot of talks on PMS, and a PMS information session and support groups and stuff like that. So that was kind of the bulk and then this weight preoccupation sort of started taking over.

I spent most of my career, I’d say, just helping people get out of diet culture. Helping people enjoy food, helping people not feel guilty, helping people feel OK about themselves, the body they happen to live in and the food they’re eating, no matter what it is.

I just loved working with women who had come in who’ve been dieting for however long, whether it was a year or 50 years. They’d often come in and say, “I feel like a load was just lifted off my shoulders,” or, “I ate some cookies, and I felt OK.” I loved doing that work with people, and that continued in the eating disorder program, too, because I worked mostly with binge eaters. I loved doing that work, and I hated hearing about the discrimination. I hated that it happened and hearing how horribly people were treated (by the medical system).

”I spent most of my career, I’d say, just helping people get out of diet culture. Helping people enjoy food, helping people not feel guilty, helping people feel OK about themselves, the body they happen to live in and the food they’re eating, no matter what it is.” – Ann McConkey

In 2009, the Provincial Eating Disorder Prevention and Recovery Program was piloted at WHC.

● Harris: That was a huge deal because there’s so much wrapped into how eating disorders happen that tie into women’s health and feminism. To be able to provide those outpatient services through a feminist lens, where there’s real treatment happening, but there’s also this understanding of where weight pre-occupation comes from and how eating disorders manifest.

● McConkey: I’m really glad we got funding to do eating disorders. But I think the hope of the program was to get more funding and be able to do more preventative work. We didn’t get that funding, so we ended up doing treatment, which is wonderful. But I always likened it to standing down river and plucking people out of the river — but if you’re not fixing the dam, it doesn’t help. I would have liked more money to go out to continue that preventative work and do way more of it. So, I think I was disappointed that it became a treatment program — which, of course, is valuable and worthwhile and I’m glad we were doing it, because we were doing it with a feminist approach, and much more holistic, which is wonderful — and we were dealing with binge eating, which the hospital doesn’t. And binge eating is totally because people diet. Like if we didn’t have dieting, you would have very, very few people who binge eat. But unless we stop the dieting, it’s going to keep on.

The Next 40: Recognition, reconciliation, renewal

When it opened in the early 1980s, Women’s Health Clinic’s work was about access, and that’s true today — but as Laurelle Harris notes, what access means has evolved. “The impact on racialized women and Indigenous women to accessing health-care services and social determinants of health, those are things that have evolved over the decades that were not necessarily on the radar, because what WHC was fighting for at the very beginning was just access, period.”

Now, as WHC embarks on a new chapter, it’s looking at what new executive director w Nembhard calls the three Rs: recognition, reconciliation and renewal.

● Dr. Scurfield: What has advocacy done for us? It’s been so much of who we are. I think it can go both ways, obviously, but I think in general it has done us well, we have support in the community. I believe the work we do is important work and if people hear, “Oh, there’s the Women’s Health Clinic talking about abortions,” they now know where to come for an abortion. So even if they’re not vocal advocates themselves, much of the information that gets out about the clinic can be around our advocacy and that leads to more people knowing about us. I’m sure there are some people who have turned away from us because of some of the stances we’ve taken, but I think on balance it’s more that we attract people by our advocacy.

● Harris: As intersectional feminists we have to recognize that we have to practise anti-racism and seeing the connections where race and gender intersect… and create entirely different experiences and oppressions for women.

Black Lives Matter is something the WHC should be committed to and is. Because there’s an important role for an advocacy organization to recognize that the women that come through the door sometimes lead incredibly complex lives and you can’t isolate what one defines as “health” and take it out of that context. You can’t do equity work if you’re not committed to anti-racism.

● Kemlin Nembhard, executive director, WHC (June 2020 to present): It’s kind of the three Rs: recognition, reconciliation and renewal. I think recognition is the first one, recognizing all of the milestones that we’ve reached over the last 40 years — and there have been a lot — and also recognizing how, in the past, we haven’t done things as well. Initially, I think it was a lot of white women, right? Straight, white women, so not representative of the population, and also only meeting the needs of a pretty small section of the population and, in fact, often leaving out a lot of people who really were in really big need of services. So I think recognizing those things, and then the harm that may have come from that.

Talking about reconciliation, which comes from that recognition and really looking how we’re doing things, how how we’re being inclusive — or non-inclusive — and looking at our services, how we deliver our services and programs, and doing a lot more collaboration and partnering, and making sure that we are moving into the future in a really inclusive way. And I know that term is used a lot, but I think it’s important, like in an inclusive, feminist, anti-oppressive way, and constantly working towards making those things better.

The third R is renewal. Every agency goes through ups and downs, kind of ebbs and flows. And I think the pandemic notwithstanding, the last five, six, 10 years have been a bit of an ebb, I think, and we need to flow now more. So working at that renewal, in partnership with communities, in partnership with Indigenous people, Indigenous communities, with communities of colour, with trans communities, with queer communities, so we need to kind of renew ourselves. (That can also involve) our physical space, because we’re embarking on a big redevelopment project, because our current building, our Graham building, which we own, is in pretty bad shape. It’s an older building, it’s not terribly accessible.

● Guzzi: Feminism doesn’t feel like a dirty word for people anymore. I mean, we want to be much more inclusive and much more accountable — like, feminism for whom? Feminism is for everybody but we have to make sure that it is accounting for all those intersections that make people feel excluded. Or that it’s beyond a white gaze of feminism. It should shift and change all the time, and it should realize where it failed and where it needs to make changes. And how to understand what does it mean to be part of a health-care system that really has done harm to people? As much as we talk about the educational system having done harm, the legal system, all these big systems do harm. They obviously don’t just do harm, but we know how it has impacted people’s lives.

WHC still struggles with the same systems, right? So it replicates some of those errors. Our hope is we patch them and we deal with them. We could not be here for 40 years without a lot of missteps. It’s about hearing and listening and changing.

”I think for me, the essence of volunteerism here is that it is a site for feminist education and transformation, but it’s also a site for, how are we going to put into practice feminist principles, especially as it looks through an anti-oppression, anti-racism lens?” – Gio Guzzi

I think for me, the essence of volunteerism here is that it is a site for feminist education and transformation, but it’s also a site for, how are we going to put into practice feminist principles, especially as it looks through an anti-oppression, anti-racism lens? What does that look like? How do you make those changes when you’re in the system? How do we unpack and reveal the built-in biases, the default thinking that happens? When you look at sexual reproductive health and reproductive justice, what does it actually mean, then, as volunteers, learning this information, taking this knowledge, our own self-discovery about ourselves, but as we move through the world, how are we going to make those changes? Because sexual reproductive health has been a site of oppression.

● Nembhard: It’s easy to lose sight of that (that it has been a site of oppression) when you get comfortable. Initially, when we first started, it was a lot of activists, right? But as you get comfortable, it’s easy to lose sight of that. The medical system, if you think about it, at its core, it’s based on cis men. All of the research, everything, is based on men. And it used to be that it was really only men that practised. And even though we have a lot more female doctors, like people who identify as female who are doctors, it actually hasn’t come that far. And that’s super important to keep in mind, and everything that we do at the Women’s Health Clinic needs to be informed by that fact.

● Harris: I was the first racialized chair of Women’s Health Clinic.

My goals and priorities were really equity-focused and focused on building a strong intersectional feminist organization that recognized that women are not monolithic and that women have very different needs. And that was happening… but it was time, from a governance perspective, to vision that in an active way.

When the organization started, it started as a grassroots organization. And, you know, our understanding of who is a woman has changed and evolved to become gender inclusive, so that folks who would otherwise fall through the cracks of what a traditional definition of woman, which is really about biological sex, was actually creating a narrow definition that we needed to get rid of in order to really embrace the changing time and the changing understanding of the construction of gender.

The organization has always done amazing work, but there’s always room for improvement and, obviously, there were people who were left behind if I was the first racialized chair and it took the organization over 30 years to get there.

For example, the board was not particularly racially diverse and we didn’t always have Indigenous representation on the board. And the other identified issue is that we had a very diverse volunteer base and a very diverse base of folks working at entry level positions, but not necessarily working their way through the organization.

● Elder McKay: We’re looking at so much of reconciliation. Like, who walks in the door and who meets you on the other side of the desk. There is not a good balance there right now and we need to change that.

They asked if I would join them and we talked about it for six months before I decided. Women’s Health Clinic is a non-Indigenous organization and I’m an Indigenous Elder used to working in Indigenous organizations, where the language, the culture is all around you. But when we talk about reconciliation, isn’t that what it’s all about? Indigenous and non-Indigenous working together?

● Harris: I think the groundwork has been laid… that was driven by the board’s recognition that the next level required women of colour and Indigenous women and racialized women in those leadership positions to really do the work as best as it can be done.

I think a major turning point was hiring our first racialized executive director (Nadine Sookermany, 2018 to 2020).

● Nembhard: It’s so important (to have women of colour in leadership positions). And I wouldn’t just say women of colour, I would say BIPOC. I think it’s so important. As a woman of colour, I know, having grown up here, I know what it’s like when you walk into a room and there’s nobody that reflects you. Just that itself is daunting. And so, I think what we want is to have the reflection all across the agency — whether it’s our practitioners, whether that’s doctors, nurses, counsellors. That’s something we need to really work on, and not to say that we’re going to be pushing people out, because that’s not the case at all. But I think as staff turns over, as things change, or we add new positions, really looking at making sure we’re trying to be more representative of the population we serve.

● Elder McKay: The clinic is 40 years old and the medicine wheel has four quadrants. If you look at them both… well, they have made their way around the medicine wheel. That last quadrant was an ending. Before you can have a new beginning, you need to have an ending so you can create space and time for the new beginning.

Our past made us who we are today. When we look at the women who started the clinic, it was white women of privilege. And when you think about how things were 40 years ago it could only have been white women of privilege who could’ve started the clinic. And they fought and they made it happen so that we have this clinic today that we can build on and add to. They did a great job, those women. And you know what? The same as anything, change comes and we needed change. We’re in the middle of change.

eva.wasney@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @evawasney

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @JenZoratti

Jen Zoratti is a Winnipeg Free Press columnist and author of the newsletter, NEXT, a weekly look towards a post-pandemic future.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.