Watershed moment WAG exhibition delves into Indigenous perspectives on precious resource at a time of ecological crisis

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 13/08/2021 (1587 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

During the Standing Rock protests against the Dakota Access Pipeline in the United States in 2016 and 2017, a Lakota phrase became synonymous with the movement: Mni Wiconi, or “water is life.”

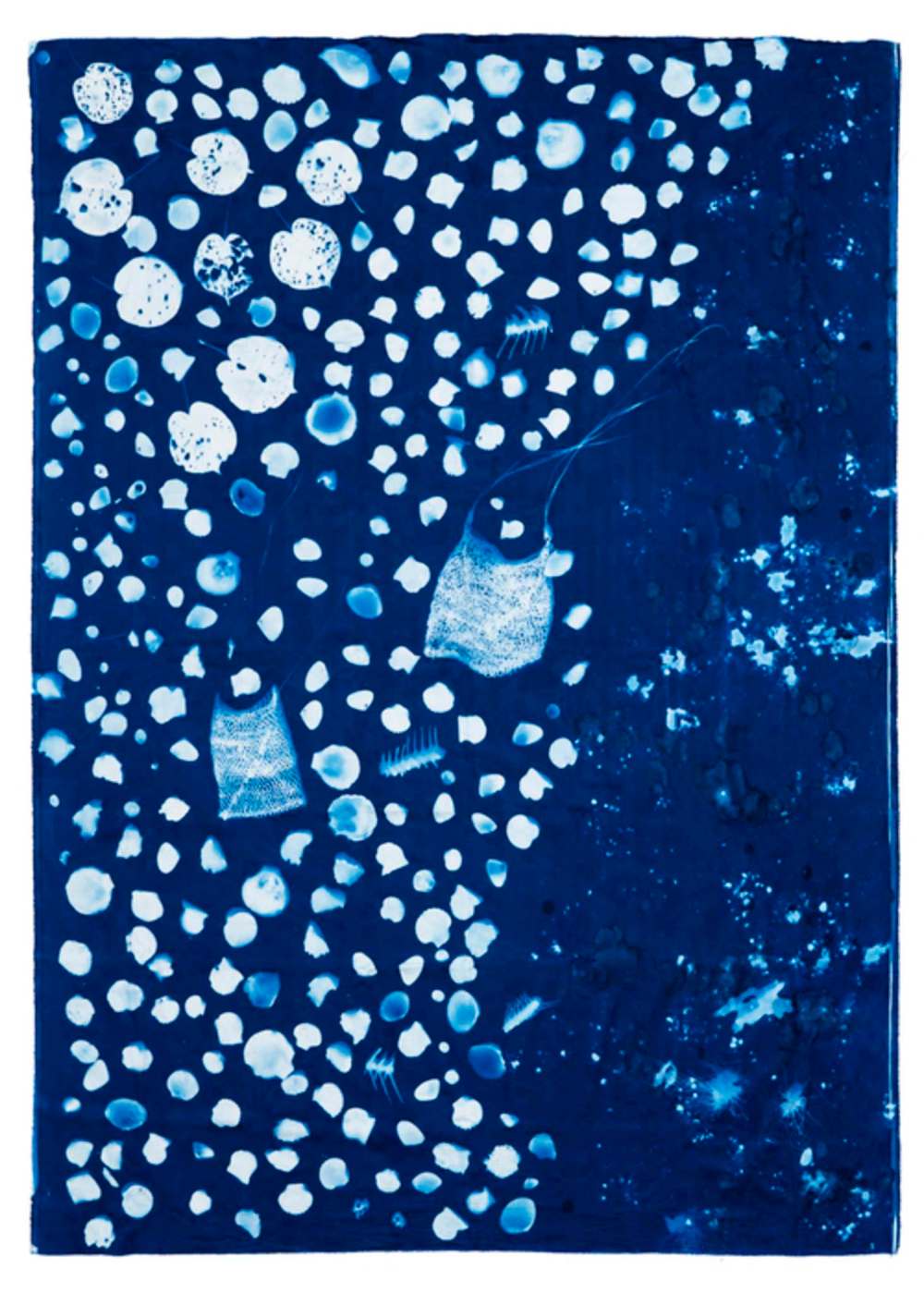

Water is life. Water is sacred. Those ideas are at the heart of Naadohbii (To Draw Water), a new, tri-national exhibition opening today at the Winnipeg Art Gallery that explores and reflects on Indigenous worldviews on water.

Curated by Jaimie Isaac, the former curator of Indigenous and contemporary art at the WAG, along with Reuben Friend and Ioana Gordon-Smith, director and curator, respectively, at Pātaka Art + Museum in Wellington, New Zealand, and Kimberley Moulton, senior curator of South Eastern Aboriginal Collections at Museums Victoria, Australia, Naadohbii features contemporary interdisciplinary artwork by more than 20 Indigenous artists from across Turtle Island (North America), Australia and Aotearoa (New Zealand).

Naadohbii also marks the inaugural Winnipeg Indigenous Triennial. Every three years, the WAG-Qaumajuq will present a large-scale Indigenous exhibition.

“The curators found parallels between Anishinaabe knowledge and international Indigenous narratives about water,” says Julia Lafreniere, head of Indigenous initiatives at the Winnipeg Art Gallery. The throughline was clear: “The international Indigenous stories all have climate protection and land protection and water protection ingrained in them.”

Naadohbii arrives during a devastating, once-in-150-years drought, and a UN climate change report issuing a “code red for humanity.” Many Indigenous communities in Canada have been under boil-water advisories for decades; water inequalities exist in Australia and New Zealand as well. According to a recent article in The Conversation, Indigenous peoples hold less than one per cent of Australia’s water rights.

Lafreniere highlights a work in the exhibition called Oh my Murray Darling by Nici Cumpston, a curator and educator from Australia. “Cumpston comes from the Barkindji people, and they are the people of the Barka, which is also known as the Darling River in Australia,” Lafreniere says.

The Murray-Darling basin is one of the most vital water systems in Australia, and its ecosystem is in crisis. Indigenous people have been sounding the alarm about the Darling for years; in 2019, the river saw multiple devastating mass fish deaths due to drought and overextraction.

“(Oh my Murray Darling) pays tribute to (Cumpston’s) ancestors, who knew how to sustain the environment,” Lafreniere says. “And she says, ‘One way we can nurture the rivers is to humanize them so that they can be empowered to have rights that protect them from harmful human intervention.’”

In the face of a changing climate, it’s important that Indigenous perspectives and voices on water are not only heard, but heeded.

“The Indigenous nations of the world have been keepers of the land and keepers of the water since time immemorial,” Lafreniere says. “They know the stories of the water and the land and the history of it. And not only that, but the exhibition explores ways that Indigenous nations have humanized the water, to take care of it in the way that allows for the water to speak for itself, and to have its own autonomy. So, to have that respect for it allows the Indigenous nations to protect it properly.”

Naadohbii responds to both the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as well as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Calls to Action, using art to open dialogue and effect change. “Art allows us to have conversations outside of the scope of language,” Lafreniere says. “And I think that’s what makes it most powerful, is that it can connect communities in that way, and perhaps, articulate ideas in a different way.”

The name of the exhibition, Naadohbii (pronounced nah-doh-bey), is Anishinaabemowin for “to draw/seek water” and a gift from elder Mary Courchene.

Having Indigenous names is “an important way to take up space in colonial institutions,” Lafreniere says. “It’s important to, I think, title exhibitions in this way, because oftentimes, the concepts of these different Indigenous exhibitions aren’t necessarily something that’s captured in English. In this case, Anishinaabemowin illustrates that concept perfectly in one in one word: Naadohbii.”

Naadohbii (To Draw Water) is on view until Feb. 5, 2022.

jen.zoratti@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @JenZoratti

Jen Zoratti is a Winnipeg Free Press columnist and author of the newsletter, NEXT, a weekly look towards a post-pandemic future.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.