‘It speaks to me as an erasure of history’ Grassroots effort uncovers names of 80 children who died at former residential school

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 03/08/2021 (1591 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

As Canadians face a reckoning over the legacy of residential schools, Winnipeggers are pushing to uncover the history of a forgotten boarding school in their own backyard.

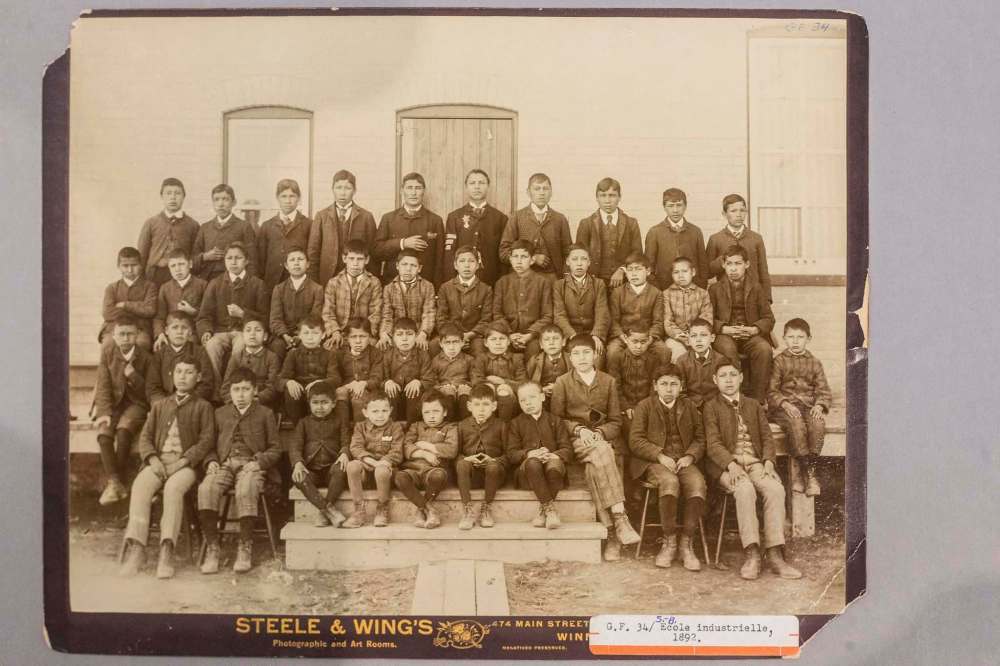

A grassroots effort has uncovered the names of roughly 80 children who died at the former St. Boniface Industrial School, which has been overlooked for decades.

“It speaks to me as an erasure of history,” said Darian McKinney, an architecture graduate and member of Swan Lake First Nation.

McKinney grew up a few kilometres from the site, without hearing about the school. He stumbled across it in an unrelated research project last year.

The recent master’s graduate is leading a mission to tell First Nations where missing children are buried, and to show Winnipeggers just how close to home these schools operated.

“This is not a distant history in our country and our society,” McKinney said.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission documented 139 residential schools across Canada, including 14 in Manitoba. But hundreds of other residential schools were never studied, based on narrow criteria in the federal settlement with survivors. To be deemed an Indian Residential School for compensation purposes, courts required a survivor to be alive as of May 2005, or to have filed a claim within a few years of that date.

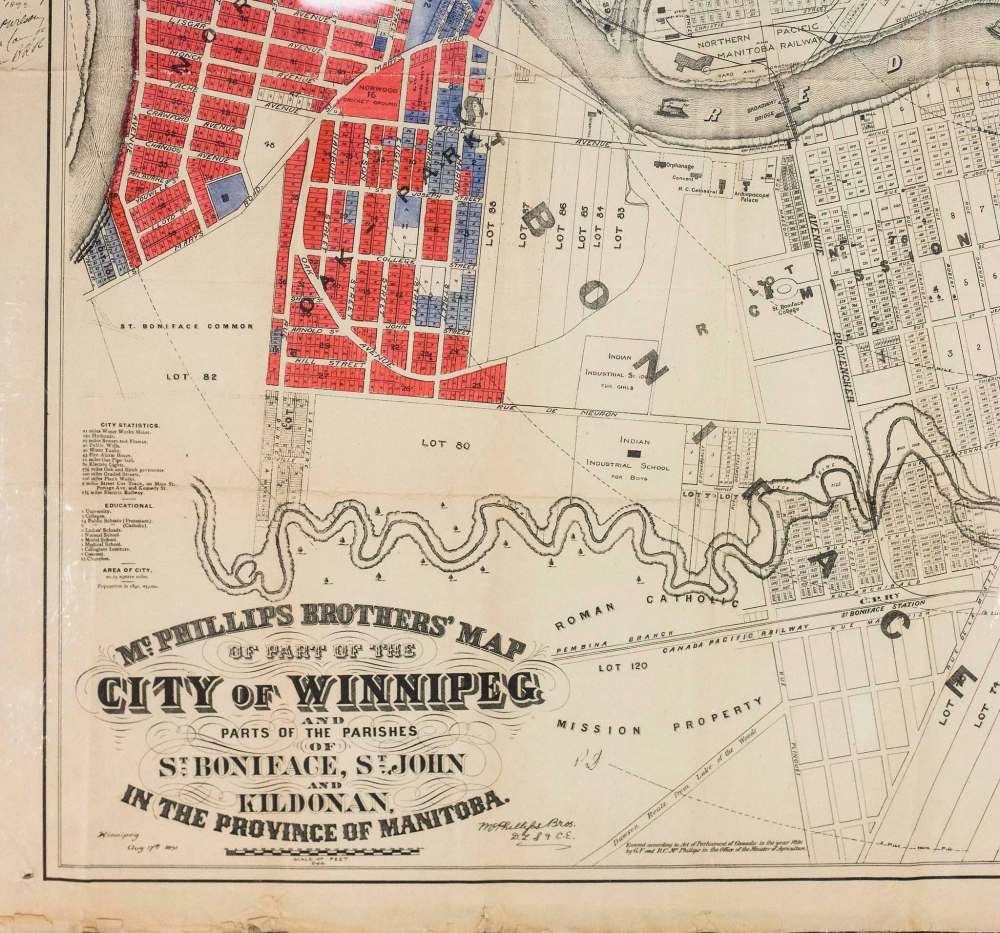

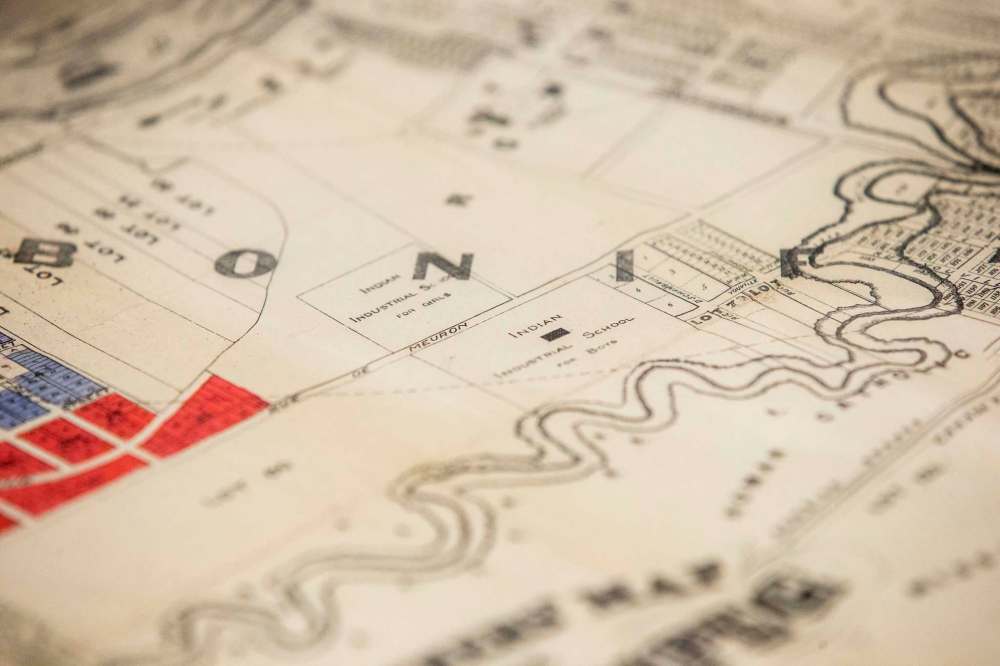

That left out a former school on Des Meurons Street at Hamel Avenue, which operated from 1889 to 1905 and was funded by Ottawa.

Government reports documented happy students living in “beautifully situated” dormitories, with access to “wholly constructed” classrooms, a cattle barn, a carpentry and shoe shop and an infirmary.

But in letters from the same period, nuns told priests about multiple deaths and “savages” running away.

St. Boniface Hospital patient logs from 1890 to 1894 document pupils with tuberculosis, scarlet fever, measles and pneumonia, often treated by the same doctor.

“These are not minor sicknesses,” said Janet La France, director of the Société historique de Saint-Boniface.

“These kids are sick all the time; repeatedly being admitted into the hospital, sometimes for months at a time,” she said.

“There are kids who I don’t know if they spent any time at the school at all, because they were constantly at the hospital.”

Other records document poor nutrition, arduous labour and cramped living quarters.

La France has been looking into the documents since establishing contact with McKinney in June.

She’s spent considerable time going through uncatalogued files of Oblate missionaries, burial records, hospital files, federal archives, and correspondence between nuns and priests.

Have information?

The team assembling documentation about the St. Boniface Industrial School wants to hear from anyone with knowledge of the school. They can be contacted at: St.BonifaceIndustrialSchool@gmail.com

Anne Lindsay, an archivist who specializes in residential schools, said those records suggest students were abused.

“The fact that you’re seeing deaths of students is evidence of the kind of physical harms that are being done,” she said.

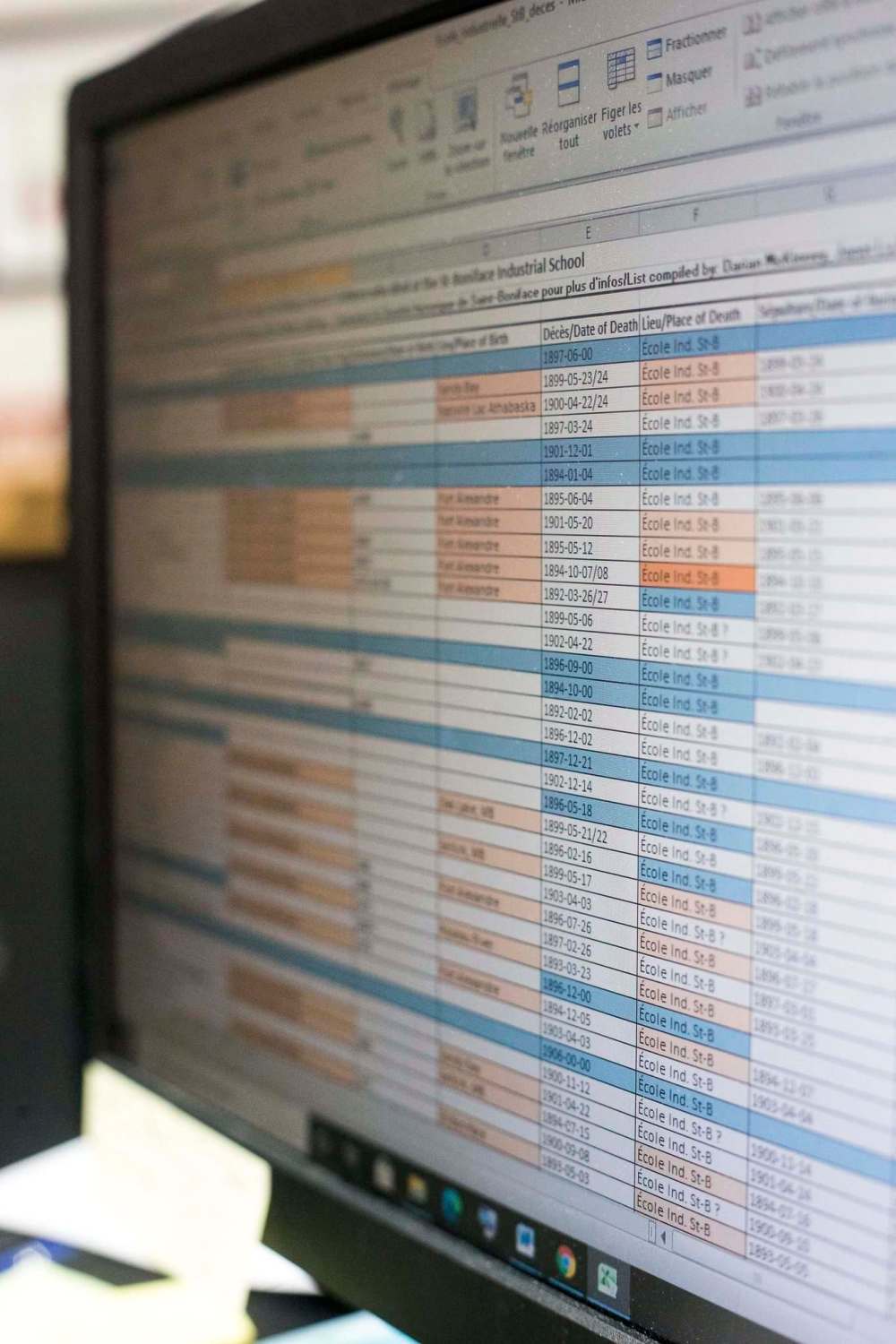

The pair have made a list of 67 children, all named, who likely died while attending the school, along with 25 children who died or were sent home sick but had likely attended the school, as records had described them as an Indigenous child.

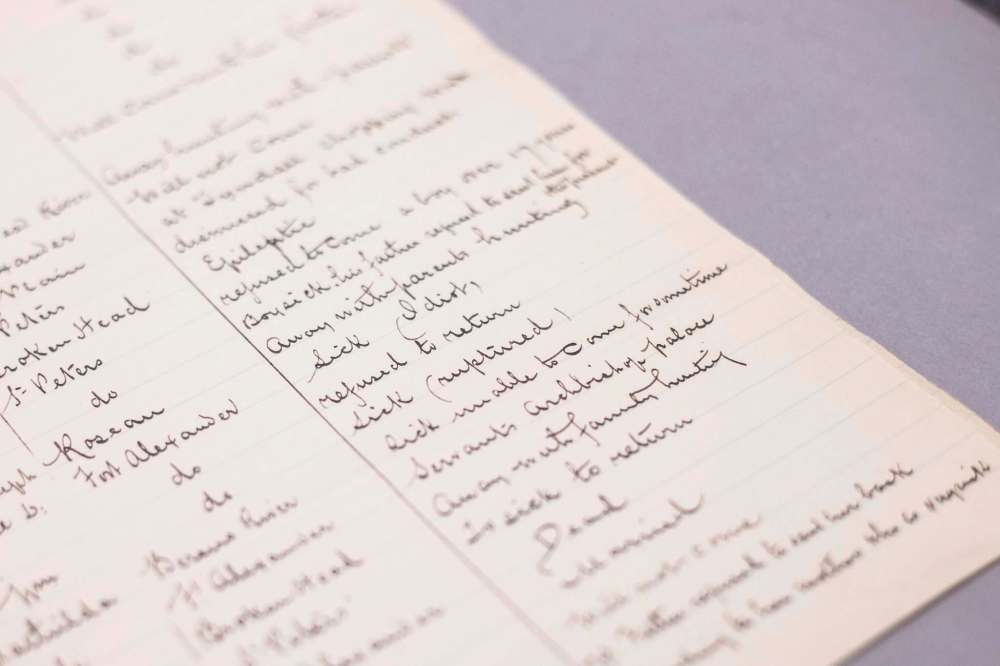

At her office on Provencher Boulevard, La France sighs as she pores over photocopies of an 1891 sick log from St. Boniface Hospital. It lists patients’ first and last names, ages, hometown and illness.

“This is really difficult stuff,” she says, flipping through the pages.

Dozens of sticky-notes poke out from the side, each representing a child who died while attending the school.

Some appear on annual registers of returning students, where they’re marked “too sick to return” or “will not come” back to school.

The same names show up in filings of post office savings accounts, which officials closed when a child died, and transfered the money to their relatives.

Burial records list some of those same names, along with their reserve, parents, cause of death and burial site, which is often the St. Boniface Cathedral cemetery.

Others don’t have a specified burial site, and could be interred anywhere on church land, which ran from Provencher Boulevard south to almost Marion Street and from the Seine to Red rivers.

Students often served as the official witness when fellow pupils were interred; Ottawa rarely returned dead children to their families.

La France says that never happened to non-Indigenous children.

She’s faced pushback when raising the issue with Winnipeggers, who often talk about the lax sanitary standards of the day, and higher child mortality.

“There is a big difference in the volume, and the types of sicknesses they’re suffering, and how often they’re sick,” she said.

“As much as people want to minimize this as being a normal fact of the time, what Indigenous kids were going through is distinct from what non-Indigenous kids were going through.”

The commission made the same point in its final report, with data analysis showing that residential school children died at much higher rates and had far worse health care than their peers in regular schools.

Lindsey noted that the Catholic schools in Manitoba were run by nuns who took a vow of poverty, meaning the school only had to supply room and board for sisters, who didn’t receive an income.

“These schools depended very heavily on unpaid student labour. The goal was ultimately that they would be self-supporting,” Lindsay said.

Many of the schools generated revenue by running printing presses or making shoes, to meet Ottawa’s treaty obligation to provide Indigenous kids with a decent education.

“There’s a lot more to understanding the experiences of the students and how the system used their labour, than what we’ve looked at,” Lindsay said.

The school was part of a federal policy to strip Indigenous children of their language and culture. Today, there is little trace of the school, which closed because First Nations families withheld their students.

“For some time it has been evident that the recruiting of children for the St. Boniface school was becoming more and more difficult,” reads a June 21, 1905 article in the Free Press, announcing the school’s closure

“The children become homesick, with a strong tendency to run away from school.”

Ottawa built residential schools closer to reserves, while Oblates converted the St. Boniface buildings into a school for priests.

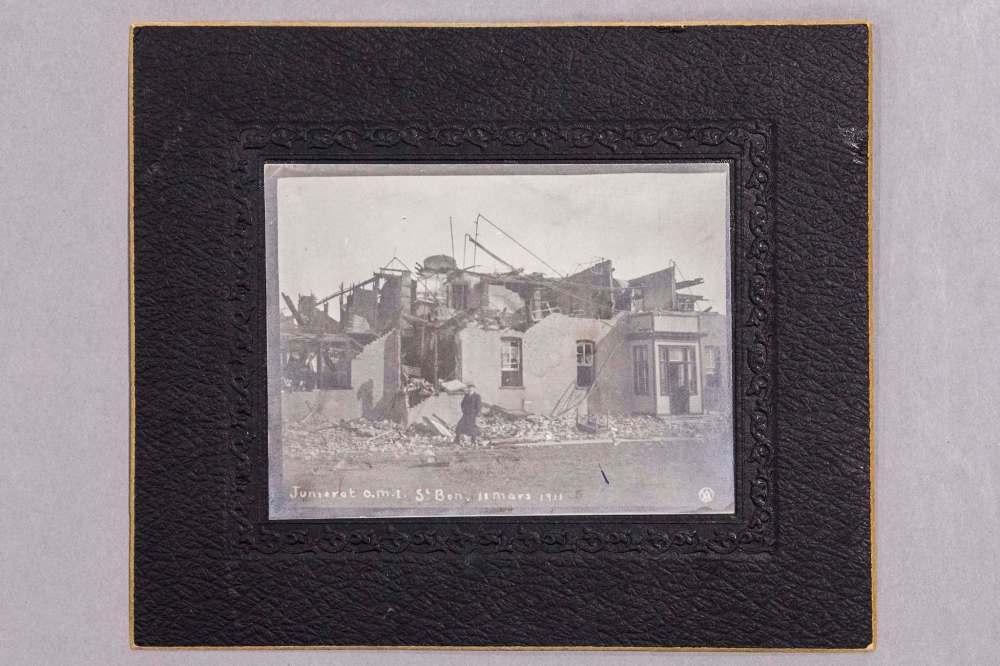

The main buildings burned down in 1911. Today the site of the former stable and ice house is an empty field, while industrial buildings sit where the dormitories were located, on Des Meurons Street.

“It’s always bothered me, being a resident of St. Boniface, and a francophone and a Métis person, that people just don’t know about it and don’t really seem to care,” said La France, who suggests a cairn or marker should be placed at the site or in the cathedral cemetery, if Indigenous communities want that.

“It’s really about letting these communities speak for themselves. It’s about their own stories (and) it’s their children and their kin,” said McKinney.

“They have to make the decisions on what happens there.”

Children who attended the school were taken from reserves such as Sagkeeng, Peguis and Brokenhead.

Two of McKinney’s grandparents attended the Sandy Bay residential school, and his great-grandmother was sent to one in Portage la Prairie, and he only has a rough idea of what they went through.

“It’s still something that is very traumatic to people,” said McKinney.

It pains him that others with a similar experience at St. Boniface don’t have formal recognition.

“We should be fighting for these people that were affected by this, and lived their whole lives without getting to see it brought to justice, or recognition,” McKinney said.

If those communities want more information, the bands might be able to commission experts using government funding.

La France says it will take experts to sift through so many documents, which are in French, Latin and English, and make the information useful to the affected communities. Many records were lost when the school burned to the ground, and in 1968, when the St. Boniface Cathedral was destroyed by fire.

On top of that, researchers must have the ability to cope with hearing about the trauma inflicted on the children.

“I’ve been having nightmares and trouble sleeping at night, because I’m dreaming of finding dead children in my home,” La France said.

The quest has taken on urgency because the site recently went up for sale, despite La France asking the city to flag it because it could contain human remains.

Lindsay says grassroots groups have done a remarkable job of documenting schools using the memories of locals and linking that with whatever records exist.

“Really grasping the historical depth of the schools requires that we look at all of them, not only the ones that were addressed by the settlement agreement,” said Lindsay.

The National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation has a public list of 202 names of children who never returned home after attending residential schools without their family knowing what had happened to them.

“There are a couple kids on there, that I can confirm died at St. Boniface,” La France said.

“These kids are still remembered in their communities. It’s not that long ago, and people have a right to these answers.”

Have information?

The team assembling documentation about the St. Boniface Industrial School wants to hear from anyone with knowledge of the school. They can be contacted at: St.BonifaceIndustrialSchool@gmail.com

dylan.robertson@freepress.mb.ca

History

Updated on Tuesday, August 3, 2021 6:12 AM CDT: Adds photos

Updated on Tuesday, August 3, 2021 8:28 AM CDT: Reorders photos

Updated on Tuesday, August 3, 2021 8:51 AM CDT: Clarifies that McKinney is an architecture graduate

Updated on Tuesday, August 3, 2021 9:34 AM CDT: Cleans up photo cutline

Updated on Thursday, August 5, 2021 8:15 AM CDT: Clarifies graph on Catholic schools operated by nuns who took a vow of poverty