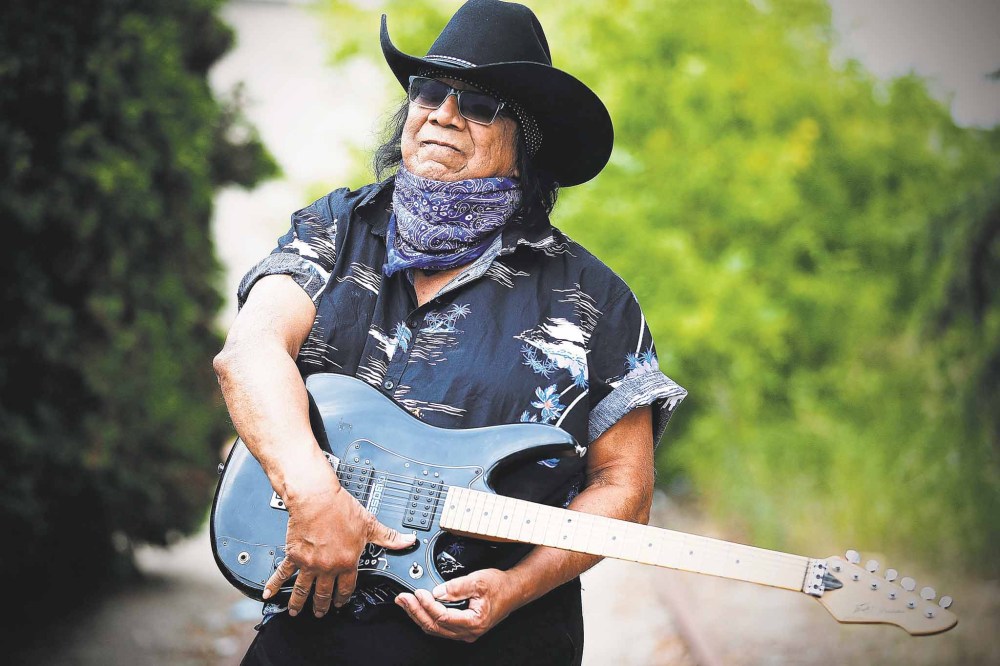

Green knows the blues Music has long been a true lifeline for Anishinaabe guitarist

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/07/2021 (1683 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Billy Joe Green has had school on his mind a lot lately.

The Anishinaabe blues guitarist, who says next year he’ll be “698 years old; that’s my spiritual age,” is a member of the Manitoba Indigenous Hall of fame. On Thursday, he headlines the opening night of the Manitoba Indigenous Music Weekend at the Pyramid Cabaret.

Despite all that, he says one of his pandemic projects was — get this — learning how to play guitar.

Manitoba Indigenous Music Weekend

July 29-Aug. 1, 8 p.m., Pyramid Cabaret

• July 29: Billy Joe Green, the Bloodshots, Rescued by Dragonflyz, the Shades of Dawn ($20 in advance at Showpass.com / $25 at the door)

• July 30: Tracy Bone, Desiree Dorion, Kimberly Dawn, Frannie Klein, Kristen McKay, Lachelle Reanne ($25/$30)

• July 31: Jerry Sereda, Gator Beaulieu, Fred Mitchell, the Resilience, Lucien Spence, Band of Brothers, Martin Desjarlais Band ($30/$35)

• Aug. 1: C-Weed, Eagle & Hawk, Keewatin Breeze, Mosquitoz 2.0, Darren Lavallee, Rhonda Head ($35/$40)

“I went online and been getting guitar lessons from this young guy who’s probably 19 years old. I’m finally learning how to play the guitar properly,” he says. “I’ve been playing it wrong all these years.”

Green has lots of great stories to tell from his three decades in the music business, but he grows far more serious when asked about where he first learned to play the guitar: the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School near Kenora.

“We had one (guitar) sitting around at the residential school. We would fight over it; everybody wanted to play. But once in a while I’d get my hands on that Stella guitar and experience how that guitar sounded in my own hands,” Green remembers.

The Cecilia Jeffrey school is familiar to Canadian music fans because it’s the institution Chanie (Charlie) Wenjack was taken to in the 1960s. The Ojibwa boy’s life story, and his death in northwestern Ontario while running away from the school, was brought to wide attention by Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie, whose solo album Secret Path — which led to an animated TV movie — detailed the tragedy.

Green knows the story well because Wenjack was one of his classmates.

“It was an impossible task,” Green says of Wenjack’s attempt to find his way home. “We still hurt over that situation with Charlie Wenjack. It was 1966 — we were all just young boys.”

Music is about the only fond memory Green has of the school, which he says despiritualized and dehumanized the children who were forced to live there.

“It was a terrible place, really, but the one thing I did learn from there, they’d play a stack of records over the PA system,” he says. “They’d play Elvis Presley, Hank Williams, Johnny Horton and the British Invasion, the Yardbirds, the Beatles and Rolling Stones, so I got a good taste in music as I was going to sleep.

“That’d be the only good thing I could say about that hellhole.”

It’s been about half a century since Green was at the Cecilia Jeffrey school, but recent discoveries of unmarked graves at other former residential schools in British Columbia and Saskatchewan brought back bad memories and difficult emotions.

“We still hurt over that situation with Charlie Wenjack. It was 1966– we were all just young boys.” – Billy Joe Green

“We were already aware of the stuff going around, but when it hit the news like that, it was just like another slap in the face,” he says. “I literally wept in my chair where I’m sitting now. I teared up uncontrollably.

“I’m an old guy, I shouldn’t be crying at my age, but I cried.”

Green took the chords he learned, and his childhood memories of his father David playing and singing country blues songs made famous by Jimmie Rodgers and Wilf Carter, to try his hand at the music business.

He “turned pro” in 1968, and moved across the western part of North America, wherever his guitar could land him gigs. Stops in Vancouver, Edmonton, Saskatoon and San Francisco, among other places were interspersed with stops back in Winnipeg, including a short but memorable stint with the C-Weed Band.

Errol Ranville, the man behind the C-Weed moniker, found mainstream success by covering the Band song Evangeline and needed another guitar player for an eastern Canada tour, and enlisted Green. The gigs were great but the bus rides were too much.

“All I could take was five weeks,” Green says, adding that his alcoholism was also a factor in the hard time he had. “Those guys were so used to travelling but they had a little trick. As soon as they got on the tour bus, they’d go right to sleep and they’d be rested by the time when we’d get to the destination.

“The music was the easy part, the fun part, but I was at the end of my rope.”

Green says he spent the next four years battling the disease and even gave up the guitar, but he says he got a second chance, and he’s been running with it, clean, ever since.

“Finally in 1991 I sobered up and I gave up everything,” he says. “A year later, what they call ‘the higher power’ gave me back my career and I started my own blues band. I became a bandleader of all things. It was totally unexpected.”

He earned Juno Award nominations for his 2000 album My Ojibway Experience: Strength & Hope, 2004’s Muskrat of the Blues and Rock & Roll and 2008’s First Law of the Land. Indigenous Music Awards and a Western Canadian Music Award would follow.

Green’s latest record, a set of collaborations with artists such as Don Amero and Sol James titled The Feathermen Family: Keeping the Circle Strong, Vol. 1, came out in 2019. Any chance to promote it in 2020 vanished, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We’ve been tied down for two years,” he says.

Green says Thursday night’s show at the Pyramid will be the first time he’s performed before an audience since the June 2019, when he was part of the Freedom Road concert at Shoal Lake 40 First Nation, where he was raised. The concert celebrated a century-long struggle to build a permanent road to the community that had become isolated after an aqueduct was built in 1919 to transport Shoal Lake water to Winnipeg.

alan.small@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter:@AlanDSmall

Alan Small

Reporter

Alan Small was a journalist at the Free Press for more than 22 years in a variety of roles, the last being a reporter in the Arts and Life section.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.