Idols no more A tour of the legislative grounds reveals a collection of statues and memorials that delivers a selective history lesson

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 06/07/2021 (1617 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

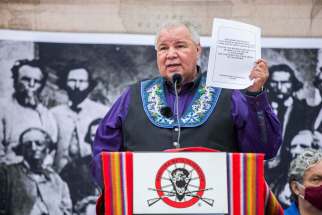

The toppling last Thursday of statues depicting queens Victoria and Elizabeth II on the Manitoba Legislative Building grounds has sparked a debate over who and what deserve to stand in stone and in bronze around the central forum of provincial politics.

Since construction of the current Legislative Building was completed in 1920, dozens of individuals, groups and historical moments have been commemorated there.

However, until those regal idols fell last week, many Manitobans, both those angered or empowered by their removal, were likely unaware those statues and others stood there at all.

So who else, and what else, is still standing? Let’s take a walking tour.

“Welcome to your journey through the richness of Manitoba’s history,” the province’s self-guided tour brochure reads. “We hope that it will help you to understand the story of the development of Manitoba and to celebrate the cultural diversity which makes up Manitoba’s mosaic.”

OK, let’s go.

On the building itself, above the front columns, is the pediment, with a “central female figure representing Manitoba.” On the east side, a nautical wheel represents the Atlantic Ocean; on the west, a hand holding Neptune’s trident represents the Pacific. On either end is a sphinx, “regarded as a sentinel or guardian whose role was to protect valuables such as the pyramid tombs of ancient Egyptian pharaohs.” In Greek mythology, the tour notes, the sphinx sat on a high rock near Thebes, interrogating each passerby with a riddle. Those who couldn’t solve it were strangled.

Also on the pediment are “an indolent man” next to a half-kneeling figure, representing “the spirit of progress,” and a depiction of Europa, a Cretan moon goddess, “symbolizing European immigration,” plus a man, woman and child, “symbolizing a family in the new land,” as per the province’s legislative tour website. (Those elements aren’t mentioned in the brochure.)

Around the base of the building’s dome are four sculptural groups representing industry (a woodcarver, a sculptor, a fisherman), art (man with compass, woman holding manuscript, woman weaving a blanket), agriculture (people holding wheat and scythes), and science (three women depicting the learning process).

Above that, atop the dome, towers the 5.25-metre tall Golden Boy, sculpted by Georges Gardet of Paris. The statue arrived in Winnipeg in 1919.

Back to the ground level, where more than 30 people, moments and groups are commemorated in the form of busts or plaques. These are short descriptions, so readers are implored to use the public library or Google to learn more.

In the northwest area is the “Next of Kin” monument, unveiled in May 1923 to commemorate 1,663 Manitobans killed during the First World War. Nearby, a pair of monuments pay homage the contributions and presence of the Ukrainian community in Manitoba. A plaque and cairn, erected in 1998, recalls the plight of Ukrainian and eastern European immigrants to Winnipeg, forcefully interned after being marked as “enemy aliens” between 1914 and 1916.

According to the Manitoba Museum, Ukrainians and others classified as Austro-Hungarian were interned at “receiving stations” in Brandon and in Winnipeg, including the former Fort Osborne Barracks, located along Osborne Street between Assiniboine Avenue and Broadway — grounds now hosting the legislature.

Beside the plaque and cairn, there is a statue of Ukrainian poet and artist Taras Shevchenko, erected in 1961 to mark 70 years since the first Ukrainian settlement in Canada.

At the west entrance, you’ll meet Major General James Wolfe, British commander at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. He died there in battle in 1759, but was memorialized in 1920 at the Legislature, sculpted by New York’s Piccirilli Brothers. You’ll also meet Frederick Temple Blackwood, a.k.a. the Earl of Dufferin, who was Governor General of Canada from 1872 to 1878 and the first vice-regal visitor to Manitoba. His Piccirilli-made statue went up in 1920 too.

Above Wolfe and the Earl is a depiction of peace, represented by two women kneeling next to an ark topped by a crown, which Melissa Funke, an assistant professor of classics at the University of Winnipeg, says likely symbolizes the Crown “bringing civilization” to Manitoba.

On the south grounds, more memorials are found: a broken Star of David to commemorate victims of the Holocaust and those who had surviving family members living in the province; a cairn marking the 40th anniversary of the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima; a young girl holding a sheaf of wheat in memory of the victims and lasting impact of the Holodomor, the forced famine overseen by Soviet authorities in the early 1930s that killed millions of Ukrainian people.

On the southwest grounds, five women hold court. The “Famous Five” — Louise McKinney, Irene Parlby, Emily Murphy, Henrietta Muir Edwards and Souris Valley-born Nellie McClung — played a key role in the Persons Case, which ultimately successfully challenged that women should be considered “persons” under the British North America Act, allowing women the right to be appointed to the Senate. McClung was instrumental in a 1916 ruling that gave some women the right to vote in Manitoba.

In recent years, the Famous Five have been reassessed: while fighting for certain rights, members often expressed xenophobic ideas and were ardent supporters of eugenics-based laws, such as the Alberta Sexual Sterilization Act, which sterilized people — mostly Indigenous women, without consent — who were considered mentally or physically “deficient.” That law was enacted in 1928 and remained in effect until its repeal in 1972.

Along the Assiniboine walkway, away from the main grounds, are a statue of Louis Riel, the leader of the Red River Resistance and undoubtedly one of Manitoba’s most famous figures, and a plaque honouring Noel-Joseph Ritchot, who led Riel’s provisional government’s delegation to Ottawa to negotiate the province’s entry into Confederation.

Nearby is also a plaque commemorating John Norquay, the province’s fifth premier. Norquay, who according to many accounts stood over six feet tall and weighed more than 300 pounds, was Métis. Not far from there is the Kwakiutl Totem Pole, carved by Henry Hunt of British Columbia’s Kwawkewlth band and donated in 1971, though it too is at a decent remove from the main building.

At the east entrance is a statue of Thomas Douglas, Lord Selkirk, “honour(ing) his leadership and role in attracting Scottish and Irish settlers to Red River.” The entrance also boasts a statue of French-Canadian explorer Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, Sieur de La Verendrye, who arrived at The Forks on an expedition in 1738; the Manitoba Historical Society notes that La Verendrye founded the first white settlements on the Canadian Prairies.

Above Douglas and Gaultier is a depiction of war, represented by a Roman soldier and an Indigenous figure.

A statue of Scottish poet Robert Burns, erected in 1936 by the local Burns club, stands pensively on the east grounds along Kennedy Street, not far from Women’s Grove, a memorial to the 14 women murdered in 1989 at Montreal’s Ecole Polytechnique.

A brief history of Queen Victoria and Queen Elizabeth II’s statues

“Queen’s Statue Shipped to Winnipeg,” an insert in the July 27, 1904, edition of the Free Press read, with the steamship Montrose bound for Manitoba.

The statue had been in the works for a while: after Victoria’s death in 1901, monuments to her sprouted up across the British colonies.

“Queen’s Statue Shipped to Winnipeg,” an insert in the July 27, 1904, edition of the Winnipeg Free Press read, with the steamship Montrose bound for Manitoba.

The statue had been in the works for a while: after Victoria’s death in 1901, monuments to her sprouted up across the British colonies. The one bound for Winnipeg was sculpted in London by George Frampton, who also sculpted similar versions to be displayed in Calcutta and Leeds, England. Winnipeg’s statue cost $15,000 and the pedestal cost $2,150 in 1904 dollars.

It was to be unveiled July 1, 1904, then known as Dominion Day, but it was delayed. By July, the statue was bound for the legislature.

It was unveiled Oct. 1. Lieutenant-governor D.H. McMillan spoke, saying that nowhere was Victoria held in as deep affection as within the Dominion of Canada. Premier Rodmond Roblin noted that under Victoria’s rule, 3.5 million square miles and 10 million subjects were added to the British Empire.

“He then sketched the remarkable rise of the province of Manitoba from an unknown and uninhabited waste, through 30 years of strong young manhood, until now it compared favourably with any portion of the Dominion,” the Winnipeg Tribune reported Roblin as saying, making no mention of Indigenous people who lived on the land for millennia.

“It was therefore fitting that a people who had benefited and prospered… under the benign influence of their illustrious queen should perpetuate her memory in the bronze of the nation, and the native stone of their own province.”

“In the name of the people,” Roblin is quoted as saying, “I now unveil this statue.”

The national anthem was played and the cover was dropped, “showing the statue in all its beauty, representing Victoria crowned, seated in her coronation chair, in state robes, with the sceptre in one hand and the orb in the other.”

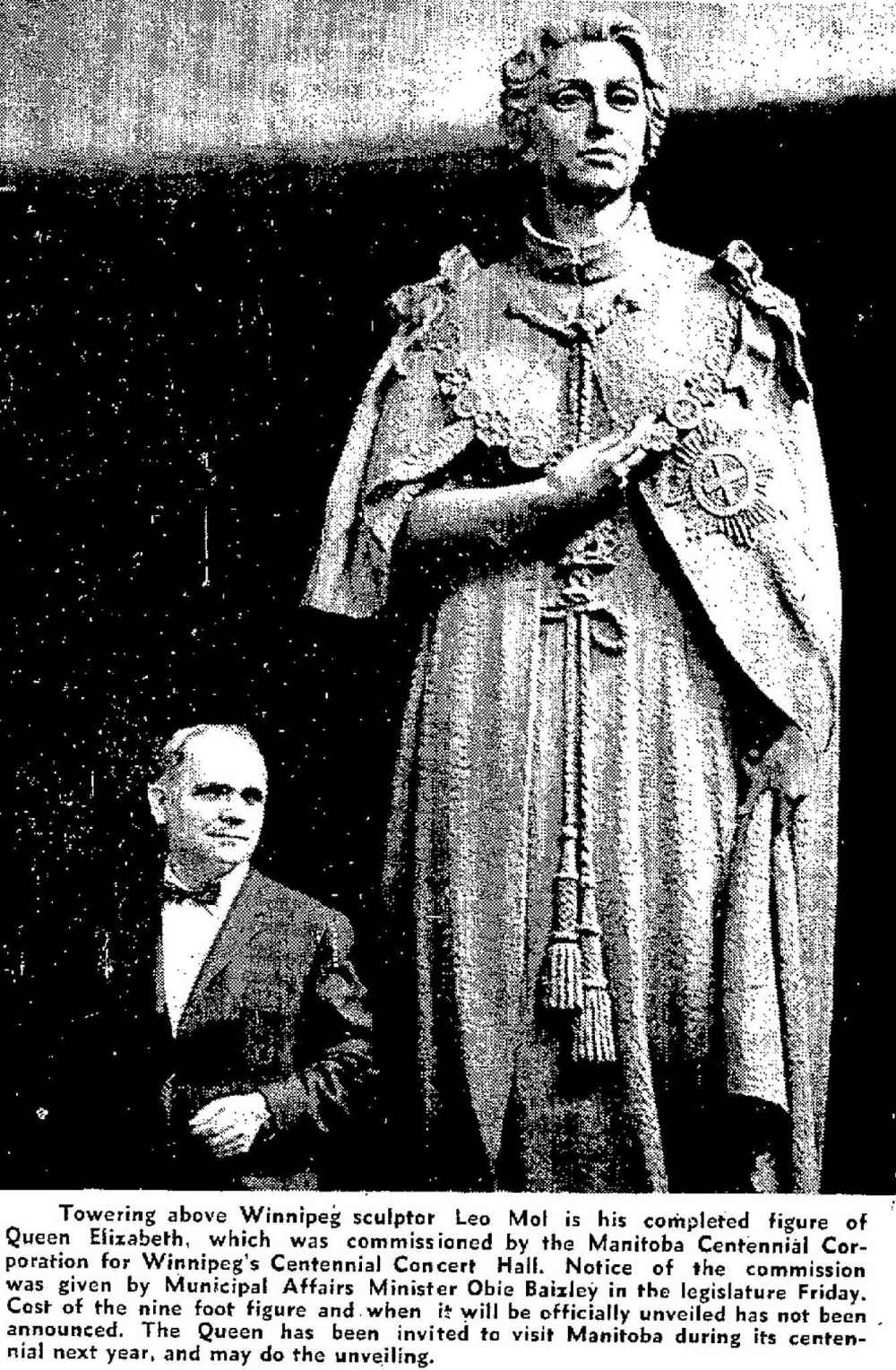

The statue of Elizabeth was completed by local sculptor Leo Mol in advance of her visit to Winnipeg in 1970, during which she visited the statue of Victoria at the legislative grounds.

The 2.7-metre-tall bronze statue of Queen Elizabeth, who has surpassed Victoria as Britain’s longest-reigning monarch, was commissioned by the Manitoba Centennial Corporation to be placed outside Winnipeg’s Centennial Concert Hall. It cost $25,000 in donations (more than $200,000 in 2021 dollars).

It had only been at the legislature for a little over a decade at the time of its removal Thursday: the statue was moved there in July 2010 for another visit from the queen.

As for the statue of Queen Victoria, Mol was critical of its placement, though for reasons artistic rather than political.

“It’s of utmost importance how they’re placed in relation to the sun,” he told the Free Press in 1991 ahead of the opening of his sculpture gardens in Assiniboine Park.

“The Queen Victoria statue out front of the legislature, nobody can really see it because it’s a silhouette. Nobody was thinking when they placed it. I don’t want that with my works.”

Go north, and find statues of George Etienne Cartier and Jon Sigurdsson. The Canadian Encyclopedia calls Cartier “arguably the kingpin of Confederation,” and his name graces dozens of streets, buildings and monuments across Canada. Sigurdsson led the 19th-century movement for Icelandic independence; his statue was erected by the local Icelandic community.

Across Broadway, Memorial Park is dedicated to Marc-Amable Girard, the premier for two brief, six-month stretches in the 1870s. Inside and near the park are a cenotaph inscribed with the names of battles Canadians fought in during the First World War and memorials for airmen and instructors who died under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan, James Bond inspiration William S. Stephenson, women who served in the military during the world wars, and peacekeepers.

The centennial survey monument there is one of 12, with one placed in 1967 on the legislative grounds of each existing province and territory. Each includes a time capsule to be opened in 2067.

Last year, a plaque was unveiled to commemorate the 150th year since Manitoba joined confederation and the 100th year since the Legislature’s construction was complete.

The walking tour guide promises a look at the “cultural diversity that makes up Manitoba’s mosaic.”

When one completes the tour, one can’t help but notice which groups are represented most, and which are represented the least. Which historical figures magisterially flank the doors, and which are harder to find. Which language the plaques are written in, and which seem not present at all. Which stories are heard there, and which have not yet been told.

ben.waldman@freepress.mb.ca

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.