Breaking the silence New book gives former students of Winnipeg's Assiniboia Indian Residential School a chance to share their stories

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 22/06/2021 (1630 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

In 1963, when David Montana Wesley was 15, his family got a call from the department of Indian Affairs. He and his school-age siblings would be taken from their home outside Longlac, Ont., to be sent off to school; nobody from the government told them where that school would be.

Online book launch

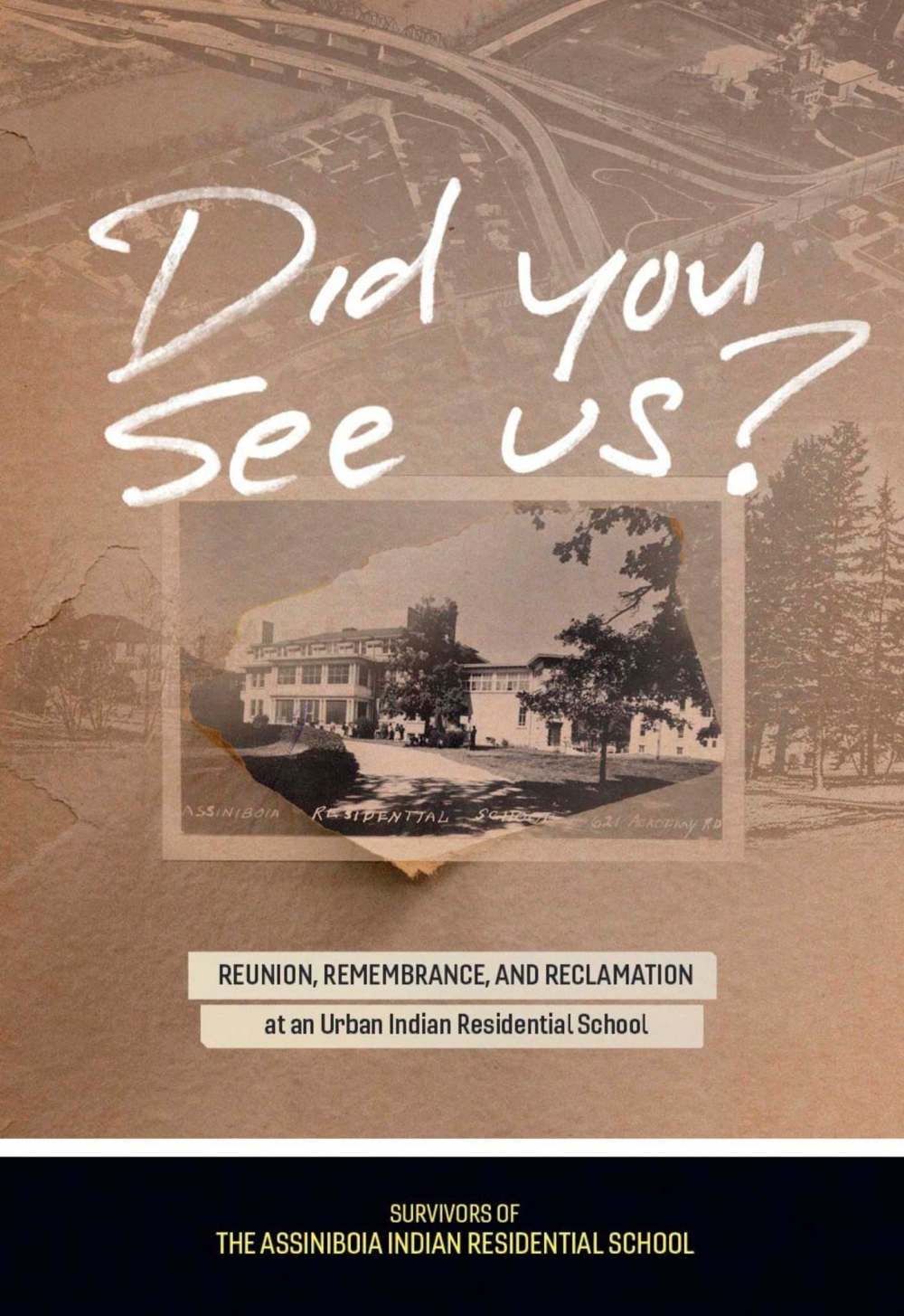

Did You See Us?: Reunion, Remembrance, and Reclamation at an Urban Indian Residential School

● Wednesday, 7 p.m.

● Register for Zoom link at wfp.to/reunion

There was a high school 50 kilometres away, in Geraldton, where he expected to go, but the bus kept going. It stopped in Port Arthur, but the schools there were full. Then to Fort Frances, where the residential school also had no room. As the bus kept going, home became farther and farther away.

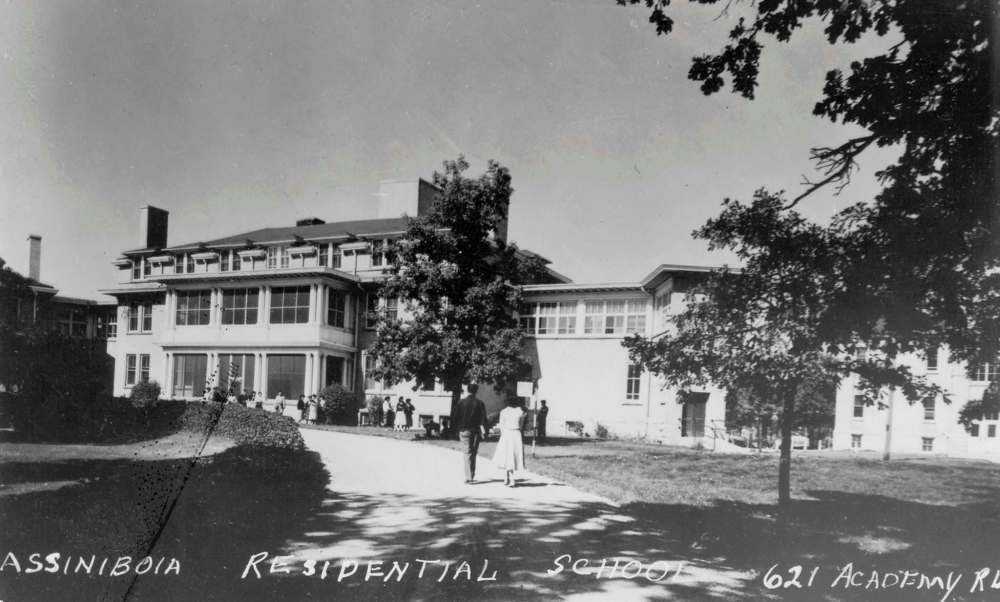

Then, the bus went to Sioux Narrows, where two of Wesley’s younger siblings were taken off to go to the small school in town. The wheels kept rolling until the bus arrived in Winnipeg, where Wesley and his other siblings ended up at the Assiniboia Indian Residential School in River Heights.

“We had no idea that we were going to a residential school. We thought we were going to a regular high school,” Wesley recounts in an interview published in the new book, Did You See Us?: Reunion, Remembrance, and Reclamation at an Urban Indian Residential School, which tells the story of the school primarily through the words of its survivors.

“They told my parents that their children were going to a high school, thinking that we were going 50 kilometres away, but 800 kilometres later we ended up at Assiniboia,” he said. A world away from home. “You’re a stranger in town.”

The book was published earlier this year by University of Manitoba Press, and has since become a local non-fiction bestseller. On Wednesday at 7 p.m., the Assiniboia Residential School Legacy Group is holding a virtual book launch in partnership with the UM Press, the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, and McNally Robinson Booksellers. Event information is available at mcnallyrobinson.com/calendar.

Between 1958 and 1973, when the residential school operated, more than 700 Indigenous teenagers were sent to Assiniboia, the first residential high school in Manitoba and one of the only residential schools in Canada located in a large urban centre. It was a link in the federal residential school program, formalized by Parliament in 1920. “Canada’s residential schools policy targeted children to ensure continuous destruction of our First Nations identity from one generation to the next,” survivor Theodore (Ted) Fontaine, who died earlier this year, wrote in the book’s preface.

Fontaine, who, with other survivors and University of Manitoba genocide scholar Andrew Woolford, spearheaded the legacy group, wrote that the school’s story has long been “an enigma, a unique story left untold.” To most residents of Winnipeg, the school and its students were invisible and unseen, whether through true unawareness or purposeful dissonance: “Did you see us?” Fontaine wonders.

Some did: on one of his first days at Assiniboia, groups of “young white people” roused the boys’ dormitory awake from Academy Road, “mimicking Indian war whoops” like those on TV or in westerns.

“Each little group of five or six was letting us know what they thought about us being there,” Fontaine wrote. “I often wonder if I ever encounter any of these individuals in my life as a resident of Winnipeg.”

For legacy group member Mabel Horton, who came from Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation in Nelson House and was sent to the school from 1962 through 1967, the book’s arrival comes at a pivotal moment of national awareness of the painful legacy of the residential school system.

That awareness stems from the uncovering of the bodies of 215 Indigenous children in unmarked graves at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School last month; efforts to identify children who died at the former residential school in Brandon, which operated until 1972, are ongoing. It’s also especially valuable, she says, as an educational tool for the youth and a way to preserve the resilient stories of survivors for future generations to learn from.

“I think it’s very timely,” says Horton, who lives in Headingley. She became a nurse and later earned a master’s degree in public administration while raising a family. “It’s very important that people are aware.”

In Horton’s chapter, she writes that her time at Assiniboia was “mostly a good experience.” At a reunion in 2017, many survivors shared that sentiment, especially when compared to the brutal abuse they suffered at other schools, such as the Fort Alexander school and St. Joseph’s in Cross Lake, the pain from which they carried with them, to Assiniboia and for the rest of their lives.

“At (St. Joseph’s), the priests, nuns and brothers basically tried to crucify me because of who I was. I experienced every kind of physical, emotional, mental, spiritual, verbal and sexual abuse in that institution,” recalls survivor Betty Ross in her chapter, a disturbing and vital piece of pained writing.

“The nuns used either hot scalding water or ice-cold water, using hard bristled brushes to try to wash off my brown skin, to make it clean and white,” she writes. She was forced to memorize Bible verses in Latin, struck twice for any mistake, and was made to take tiny orange pills that made her lose consciousness each time, only to wake up “naked, cold and scared to death.” Once, for saying a Cree word, her head was slammed to the cement floor by a nun, who kicked her left ear with her Oxford shoes.

Ross arrived at Assiniboia from Cross Lake in 1962, confused and lonely, “a total shattered wreck.” A lasting image of the cultural erasure and genocidal aims of the residential school system came with the removal upon arrival of Ross’s moccasins, which were thrown away and replaced with black-and-white Oxfords.

“The abuse there was not too invasive, but was still there, only invisible,” Ross writes.

Many survivors of Assiniboia recall the staff, including Sister Jean Ell, Father Omer Robidoux and Father Laurent Alarie, fondly; Sister Ell and Father Alarie, the last principal of the school, were embraced and welcomed by several survivors to a 2017 reunion at the remaining building of the former school, which now houses the Canadian Centre for Child Protection.

This, says Andrew Woolford, makes Assiniboia especially complex in the context of the history of the residential school system.

“Engaging Assiniboia requires that we understand the variety of residential school experiences, while not using those that are on the surface positive… to somehow absolve the system,” writes Woolford, the former president of the International Association of Genocide Scholars.

The school in Winnipeg may have been a “respite from earlier violence” for some, but it was “nonetheless part of a system designed and enacted to destroy Indigenous identities, eliminate Indigenous nations, and ensure the unquestioned dispossession of Indigenous territories.”

This is an element of genocide that often goes misunderstood, Woolford says, pointing to the work of Raphael Lemkin. Lemkin, a Polish-Jewish scholar who coined the term “genocide” in 1944, wrote that it “doesn’t necessarily mean the immediate destruction of a nation, except when accomplished by mass killings of all members of a nation.

“It is intended rather to signify a co-ordinated plan of different actions aiming at the destruction of essential foundations of the life of national groups, with the aim of annihilating the groups themselves,” he wrote in Axis Rule in Europe, in a section excerpted online by the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

“It definitely was genocide,” says Horton.

The pain lasts, she says. But it’s important to be resilient, to speak, to share traditions, languages and stories — pieces of culture the system sought to destroy.

“We’re resilient, that’s for sure,” she says a week before the book launch. “As a people, and as nations. We keep carrying on for the generations to come.”

ben.waldman@freepress.mb.ca

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

.jpg?h=215)