For Justin Trudeau and Joe Biden, healing a nation’s racist past means listening to those who bear the scars

Advertisement

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4 plus GST every four weeks. Offer only available to new and qualified returning subscribers. Cancel any time.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 02/06/2021 (1321 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

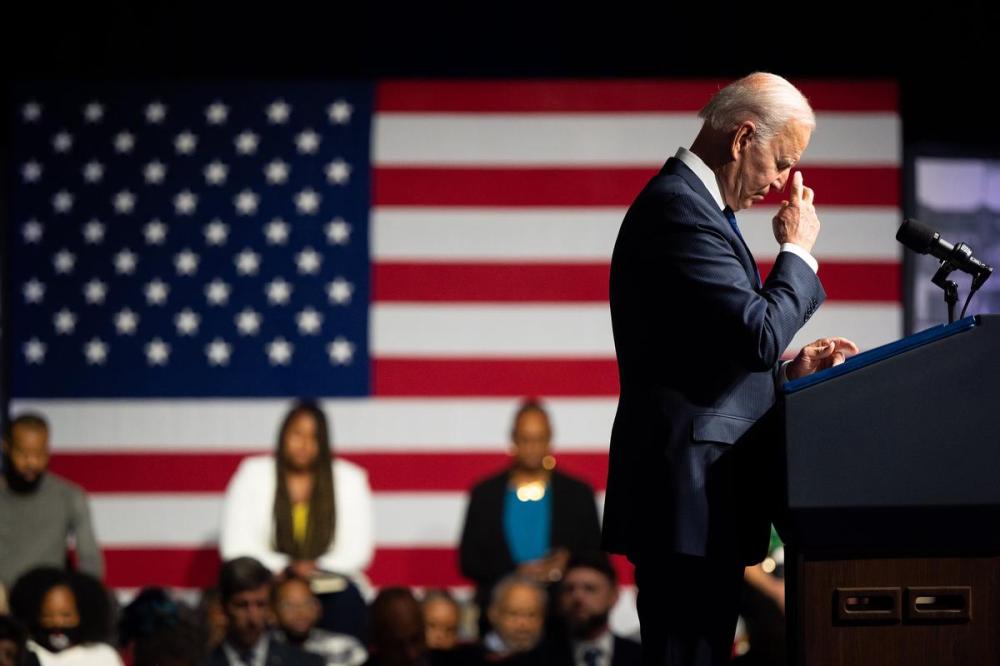

WASHINGTON—“For much too long, the history of what took place here was told in silence, cloaked in darkness,” U.S. President Joe Biden said on Tuesday in Tulsa, OK. “But just because history is silent, it doesn’t mean that it did not take place. And while darkness can hide much, it erases nothing. It erases nothing.”

Biden was marking the 100th anniversary of a racist massacre that took place in Tulsa, in a neighbourhood called Greenwood. It was a thriving Black community, called “The Black Wall Street,” full of professionals and schools and churches, shops and homes, a movie theatre.

Between May 31 and June 1, 1921, a white mob enraged by false headlines about an “attack” on a white young woman by a Black resident of Greenwood, burned its main street and its churches, along with 1,250 of its homes, to the ground. They looted businesses and homes. They murdered hundreds of Black residents.

Private planes dropped dynamite on these city blocks. “A mob tied a Black man by the waist to the back of their truck with his head banging along the pavement as they drove off. A murdered Black family draped over the fence of their home outside,” Biden recounted in his speech. “An elderly couple, knelt by their bed, praying to God with their heart and their soul, when they were shot in the back of their heads.”

No arrests were made.

For decades this horror was nearly forgotten in U.S. history. Biden, the first president to visit the site in commemoration, was aiming to ensure the story is remembered, and retold, and addressed. “My fellow Americans, this was not a riot. This was a massacre,” Biden said. “That hate became embedded systematically and systemically in our laws and our culture. We do ourselves no favours by pretending none of this ever happened or that it doesn’t impact us today, because it does still impact us today.”

“As we speak,” he said, “the process of exhuming the unmarked graves has started.”

If much of the talk of a racist history embedded in the system and cloaked in darkness could resonate in Canada, that last bit about unmarked graves finally exhumed would strike the loudest chord. For this week, Canadians are reeling from the discovery of a mass grave where 215 Indigenous children, some as young as three, were buried at the site of a residential school in Kamloops, B.C.

These children were taken from their parents, like generations of Indigenous children, in order to assimilate them into Canadian society. More than 4,000 — maybe many more — died in those schools. Many more emerged with physical and psychological scars. These schools existed for more than a century. They continued operating into the 1990s.

Many in Canada are left questioning why they were not taught about the residential school system. Or why those who designed the system — such as Egerton Ryerson — have held places of honour in our memory.

“We have to acknowledge the truth. Residential schools were a reality. A tragedy that existed here, in our country. And we have to own up to it,” Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said on Monday. He promised action — possibly funding the search for more unmarked graves at the former schools, more support for the Indigenous languages such schools sought to erase, continued efforts to “close the socio-economic gaps within Indigenous communities and non-Indigenous communities.”

The promises are fine. Though they may ring hollow for Indigenous communities which are still without clean drinking water, something Trudeau promised in 2015 they would have by now.

Biden, too, was promising action. He announced new orders to invest in Black small businesses, and in Black communities, as well as to address housing inequity. He said Vice-President Kamala Harris would lead his efforts to address an assault on voting rights that he tied to this history of racism.

“We memorialize what happened here in Tulsa so it can be — so it can’t be erased. We know here, in this hallowed place, we simply can’t bury pain and trauma forever,” Biden said.

Even as, in Canada, people wonder what was missing from their history curricula, here in the U.S., the topic of racism in history classes remains a controversial one. Republican legislatures in many states have been drafting legislation that would ban teaching history and race issues in a way that would portray the country’s history as oppressive or label white people as oppressors. Today, schools in some states still gloss over the brutality of slavery or teach that “states’ rights” and tariffs were the main reasons for the Civil War.

“We can’t just choose to learn what we want to know and not what we should know,” Biden said Tuesday. “We should know the good, the bad, everything. That’s what great nations do: They come to terms with their dark sides.”

Amid all this discussion of history, something was noteworthy about the present: attending Biden’s speech were three survivors of the Tulsa Race Massacre, aged 106, 107 and 100. One of the most emotionally resonant pieces of video from the event was of those survivors joining in to sing the civil rights anthem, “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me Around.”

When discussing how this history should be taught and remembered, it is easy to forget that witnesses — victims — are still alive. Still asking for justice. You can find them in Canada: residential school survivors, telling the stories of their lives and our country’s dark side.

In trying to come to terms with these parts of history, as Biden and Trudeau suggest we should, it’s useful to recall that the past under discussion is a living memory: the life story of people who are still here, telling us what happened, what is still happening. If only, at last, we will listen.

Edward Keenan is the Star’s Washington Bureau chief. He covers U.S. politics and current affairs. Reach him via email: ekeenan@thestar.ca