Elder-care lapses bring uneven consequences

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$1 per week for 24 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $4.00 plus GST every four weeks. After 24 weeks, price increases to the regular rate of $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.99/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19.95 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 17/05/2021 (1759 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

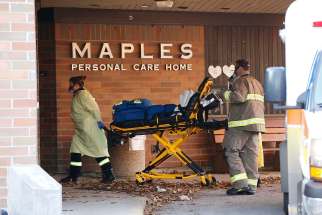

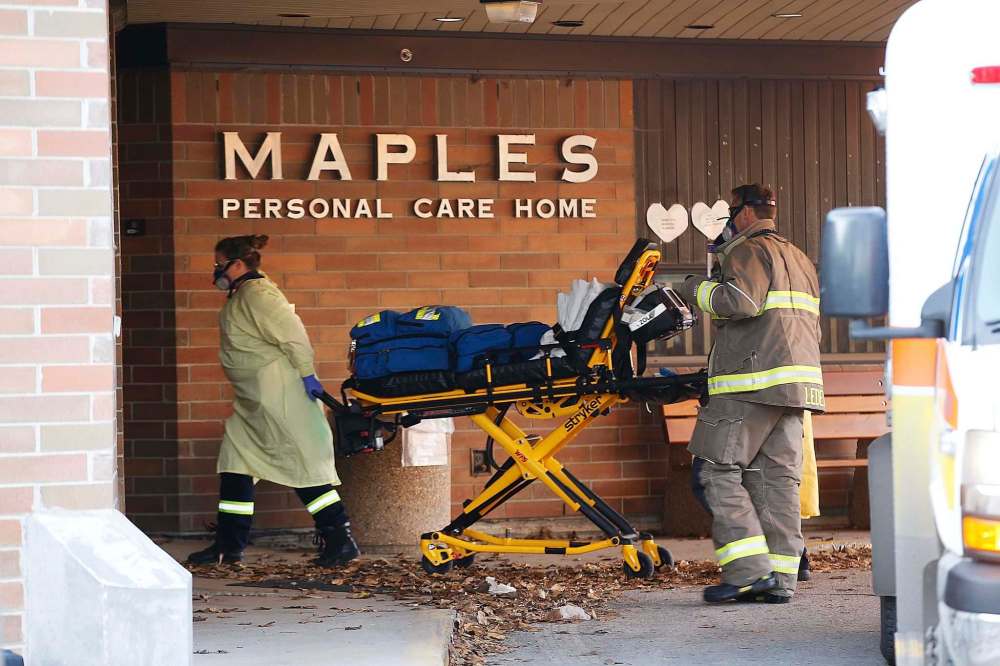

Staff at the Maples Personal Care Home called the Winnipeg Fire Paramedic Service on Nov. 6 last year because they could not care for the large number of residents who had come down with COVID-19. The paramedics took some residents to hospitals and pitched in with emergency care for the others.

At that point, it was already too late. The COVID-19 outbreak had been spreading through the facility since Oct. 20. By the time it was over, 54 residents had died of the viral infection. The province ordered an external review, which called for better plans and procedures. Relatives of some of the deceased residents are now suing the care home and the government.

By the time of the Maples care home outbreak, Winnipeg guitarist Ron Siwicki was already serving a prison sentence for criminal negligence causing death. His mother, for whom he was the sole caregiver, had died at their home in the Maples district on account of poor hygiene and bedsores after years of dementia and declining health.

The two cases show a mismatch in the consequences that are imposed for inadequate health care in this province. The son whose care for his mother was found to be inadequate was sentenced at trial to three months in prison, a term that was raised to two years by the Court of Appeal. The nearby personal-care home whose inadequate care under provincial government supervision led to deaths of 54 residents is required to rewrite its plans and its procedures.

Through much of the COVID-19 outbreak, a great many Maples care home employees booked off sick — apparently to the astonishment of the management. Untrained or partly trained new employees were hired to take the places of some absentees; even with these replacements, the number of people working in the facility often fell below 70 per cent of the usual staff complement.

Once a COVID-19 outbreak is detected in a personal-care home, the staff have obvious reasons to steer clear. If they catch the disease, they are likely to infect their families. Protection for staff health is rudimentary. Pay for health-care aides is low enough that many people would rather miss a week’s pay than expose themselves and their families to infection.

.jpg?w=1000)

The government-ordered external review tactfully did not mention the obvious problems of low pay and poor personal protection that have driven staff away from many long-term care establishments in Canada since the pandemic took hold. But even when the procedures are revised and the plans are rewritten as the review proposed, care homes will run short of staff as long as the pay remains low and the danger of staff infection remains high.

Manitoba, like other Canadian provinces, cares for its frail elderly on the cheap. The cheapest care of all is that provided at home by family members. People in need of care are often reluctant to move into a personal-care home for fear of inadequate care. Reports of terrible conditions in some nursing homes during the pandemic have undoubtedly increased those fears.

For some, the alternative is to stay home and rely on the care of family members. The imprisonment of Mr. Siwicki, however, shows that route can also be dangerous for everyone involved. The government should improve pay and safety for personal-care home workers and, while it’s at it, it should also provide training and adequate support for family caregivers. Training them would be more constructive than throwing them in prison.