Changing climate, breaking heart Science-art collaboration injects valuable dose of emotion into cold, hard truths

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 28/04/2021 (1691 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

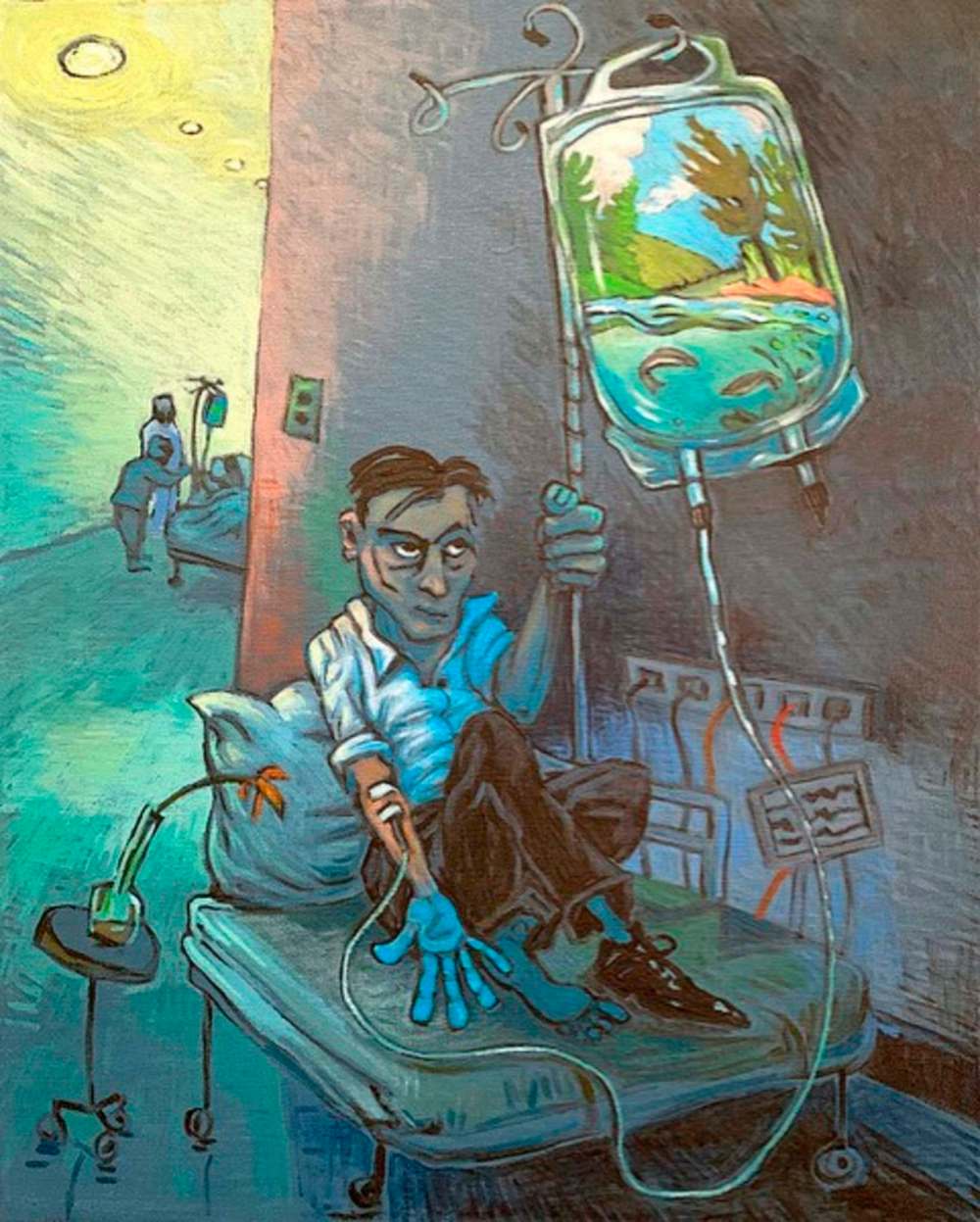

Looking at spreadsheets and map plots of trees is far beyond Rhian Brynjolson’s typical day as a visual artist, but she became entranced and inspired by data collected by Canadian scientists for a new art project.

Her hope is to try and bring the numbers, map dots and statistics to life in a new way to help the public better connect to climate science.

Falcon Lake’s Brynjolson is one of 12 Canadian artists who participated in an art-science collaboration exhibit, co-ordinated by the Global Water Futures program out of the University of Saskatchewan. The project saw the artists paired with researchers and scientists across the country who then engaged in conversations to try to inspire a new angle to their art.

“The whole idea behind it is: water is life,” says Louise Arnal, the project lead, and a post-doctoral fellow at the Centre for Hydrology and Coldwater Laboratory.

The project focuses on water but brings climate change to the foreground, Arnal explains, since it will affect hydrology in so many ways. The art exhibit examines climate effects such as permafrost thaw, the degradation of Alberta’s Peyto glacier and the vulnerability of groundwater sources.

“Science does not always involve people emotionally, so that is why we need to add this creative, emotionally connective component,” Arnal says.

Brynjolson was paired with the University of Waterloo’s Jennifer Baltzer, the Canada Research Chair in Forests and Global Change; together they started talking about permafrost thaw and its impact on forest ecology.

“It was a pretty steep learning curve, I have to say,” Brynjolson says.

“Our conversations evolved to include links to academic papers, and so on. And it was very interesting listening to her speak. She’s very passionate about what she is talking about; very knowledgeable. But what was also interesting was I thought that I was pretty aware of climate change and the rate at which it was happening, but what they’re discovering in the North about how quickly permafrost is thawing is, is pretty alarming.”

She quickly became focused on the increasing prevalence of drunken trees — trees or entire swaths of forest that lean at angles out of the ground as the thawing permafrost weakens the trees’ anchors in the soil.

“I built a mobile. You know, the idea of hanging by a thin thread. But then I started painting and what became really interesting to me was to look at the data, to look at the graphs and the plot grids, the maps of tagged trees they were keeping track of, and then superimposing that on the landscape,” Brynjolson says.

Tricia Stadnyk, an associate professor who specializes in hydrology at the University of Calgary, says she was excited about being asked to work on the project, but that it was far from her comfort zone.

“I was actually super-nervous coming into this project. When they asked me to participate, I’m like, ‘Oh no, I can’t do this.’ I’m probably the furthest removed from an artist that anybody can possibly be. I draw stick people, right?” Stadnyk says with a laugh.

She was paired with Manitoba artist Bob Haverluck to explore the impact of the Manitoba Hydro Churchill River diversion into the Nelson River. She was floored by how freeing it was to think of all she knew from a new perspective, she says.

Using photos from before and after hydro generating stations were established, Stadnyk and Haverluck engaged in emotional discussions about what they were bearing witness to.

“And then thinking about the effects of climate change and participating with all the other artists and scientists who were doing the same. There were a couple times that a few of us on the call were, like, tearing up, because it really is disheartening, scary,” Stadnyk says.

Working in a field where science and data are typically detached from emotion, Stadnyk says the experience helped deepen her connection to her work, but she adds that it isn’t something all scientists would be willing to explore.

Haverluck hopes his pieces documenting the changes in the Nelson River system serve as a reminder that even Manitoba’s so-called clean energy has a substantial cost to it.

“There’s a way in which the North is sort of non-existent for the south. We know our electricity comes from up there, there’s dams up there. But the edge of cottage country has long been seen as the end of Lake Winnipeg (to southerners), which has long been a problem. So part of it is to remind the South what’s happening in the North to which our life is tied, our lights and heat are tied,” Haverluck says.

Brynjolson hopes to see more collaborations between artists and scientists to help reframe how we view human relationships with the planet.

“I think what these conversations between artists and scientists can help us do is imagine the scenarios more fully; use surprising metaphors that jolt us out of our comfort zones and our now-outdated patterns of thinking; provide images that depict the seriousness of what the data is revealing — and also show the heartbreaking beauty of what’s being lost.”

The Virtual Water Gallery opens online April 29 at www.virtualwatergallery.ca.

sarah.lawrynuik@freepress.mb.ca

Twitter: @SarahLawrynuik