Prairie palace They say a man's home is his castle; grand old Queen Anne house takes the adage literally

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/04/2021 (1695 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

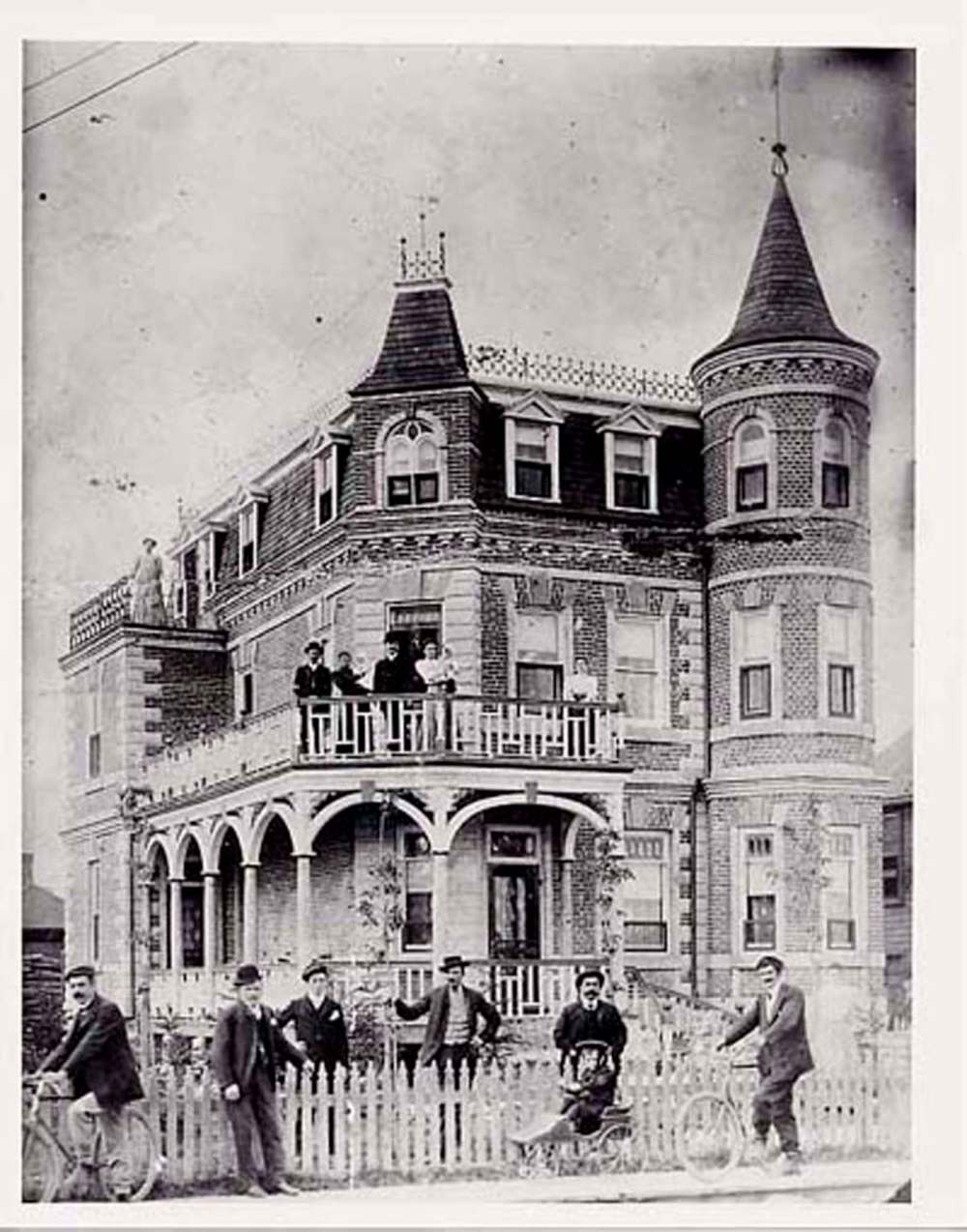

To call the house at 494 College Ave. anything other than a castle would seem wrong, so we’ll call it the Castle. It’s three storeys tall but seems taller, 115 years old but seems older, and it is right smack in the middle of a neighbourhood, right in the middle of a city, where its turreted existence inspires confusion, bewilderment and a touch of awe. It’s a place both out of time and out of place, but somehow, it feels like it’s exactly where it belongs.

“It definitely stands out around here,” says Ryan Lavallee, a 33-year-old man who lives two doors down, on the second floor of a house without turrets of its own. “Kids are always stopping to look at it. Even adults do. I have.”

In 2015, Vanh Thiep Hoang looked at it, and couldn’t stop. Hoang had come to Winnipeg with his family from Vietnam, where he worked as a surgeon. He marvelled at the Queen Anne-style castle — its gabled roof, its orange bricks, its ten-foot ceilings, and its playful disregard of convention and defiance of expectation. It cast a bit of a spell.

“It reminded me of palaces I’d seen where I was from,” and of buildings in Ukraine, where he studied, says the 63-year-old Hoang, who emerges from the castle’s front door wearing board shorts and metal-rimmed glasses, his thick head of hair as attention-grabbing as the castle he calls home.

So he bought it, and has resided there for the past six years, renting out the top two storeys and living on the main floor with his family.

But now it’s on the market, listed for $315,000, with Hoang and his family eyeing a move to British Columbia. Realtor Cam U. Tang says that at over 3,000 square feet, the home will make its next owner feel like a king, and that isn’t a stretch.

“When he told me the address, I knew the area, but not the house,” Tang says. But he did some investigating and saw that 494 College Ave. was no ordinary listing.

“I saw that this was a castle,” he says. “In 35 years in real estate, this is the most unique house I’ve listed. You don’t see many like it.”

● ● ●

When the Castle was built in 1906, it was built to be noticed by newcomers looking to leave their mark on the city.

According to the city, the house was commissioned by John Arbuthnot, a lumber merchant and the city’s mayor from 1901 to 1903. To design and construct the home, he enlisted a group of Italian immigrants led by Santi, Angelo and Olivo Biollo, brothers who came to the city from Venice in the early 20th century.

As documented in local historical site West End Dumplings, as well as in local newspaper and city archives, the Biollos quickly made good in several industries, investing in restaurants and hotels, and eventually founding a construction company. “Their first project was the Mount Royal Hotel on Garry Street,” West End Dumplings’ Christian Cassidy wrote. Today, that hotel is called the Garrick.

Then came the Castle, where the brothers lived for a few years after building it: Arbuthnot never lived there but rented it to Olivo Biollo.

City historical officer Murray Peterson calls it one of Winnipeg’s best examples of Queen Anne architecture, a style popular at the time but not very much so now.

“It’s spectacular because there’s so much going on with it,” says Peterson, who said the prewar period in which it was built was like the Wild West for residential development; home building happened without much restriction. Many unique houses, including several nearby, sprung up in short order. Perhaps none as unique as the Castle still stand.

But as quickly as success came, so did heartache. One Biollo brother, Angelo, lost three of his children to scarlet fever in a single week in 1907, Cassidy writes, and soon, a “typographical” error led to the demise of what was a burgeoning business empire.

The hotel was intended to be a “wet” establishment, selling liquor to the public, and the brothers were under the impression that it was in the legal liquor-selling zone set out by the province. But the commissioners refused a liquor permit, effectively killing the Biollos’ investment of $60,000. (Meanwhile, a neighbouring hotel got a licence.)

By 1909, Olivo Biollo told the Free Press he felt “grossly wronged,” as he lost everything he had in short order. The hotel was sold off at a loss, assets were seized to pay off debts.

In 1911, Santi Biollo was still listed as the occupant of 494 College Ave., a city report shows. But a few years later, the Castle got its next king.

• • •

His name was David Cantor. He came from a town in Poland called Miedzerich in 1903, brought to Winnipeg in principle to become a rabbi at Tefereth Israel Synagogue, as well as a shoichet (ritual slaughterer) and mohel (circumcision practicioner) for the growing Jewish community. He and his wife, Ada, along with their children, were the first immigrants to Canada from their district.

For a few years, they lived in a smaller abode. But in the 1910s, the College Avenue house came on the market, and the Cantors — who over the previous decade had written glowingly about Winnipeg to townspeople in Poland, resulting in the estimated immigration of more than 600 families of Ashkenazi Jews to Canada — moved in.

“Let me tell you about the house,” says Allan Cantor, the grandson of David and Ada, now in his early 90s and still living in Winnipeg with his wife, Gloria. “You gotta understand. I was just a child, but this is what I remember and what I know.”

The house was massive. In those days, a wide veranda spanned the second floor, painted dark green. To the south, there was at least 12 or 15 metres of lawn; it’s where his grandparents celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary in 1936, wearing the same clothes they wore in Poland half a century earlier, and where his parents celebrated their engagement party.

To the front of the building, there was a “wonderful fountain,” which ceased to work in 1931 or so because the water was redirected to a dental office on the second floor run by an uncle, Cantor recalls.

In the back, there was a barn, where the elder Cantor would slaughter kosher chickens. The kitchen floor had a trap door that led to the basement. The ceilings were marvellously high.

Over the years, as dozens of Jewish immigrants arrived from Poland, they’d come to the Cantor house for help. Most businesses wouldn’t hire the men for work because they required a day of rest on Shabbat, or the Sabbath, and Cantor would help them find their way as shopkeepers or pedlars, jobs that allowed for their continued religious observance. He helped them co-ordinate payments to bring their families over from Europe, Allan says, often depositing their money on their behalf to the banks and keeping track of when they had enough.

Once, family lore goes, Cantor told a stove salesman he had a beautiful stove to sell him. When the salesman arrived at the Castle, he found a wagon covered by a large curtain. He removed the curtain, and underneath were his wife and kids, just arrived from Poland, which startled the salesman and left him in disbelief.

“That’s a stove that will keep you warm all year,” is what the rabbi said, Allan recalls.

Rabbi Cantor died in 1953 at the age of 88, his wife in 1954 at the age of 89, and the house was sold thereafter.

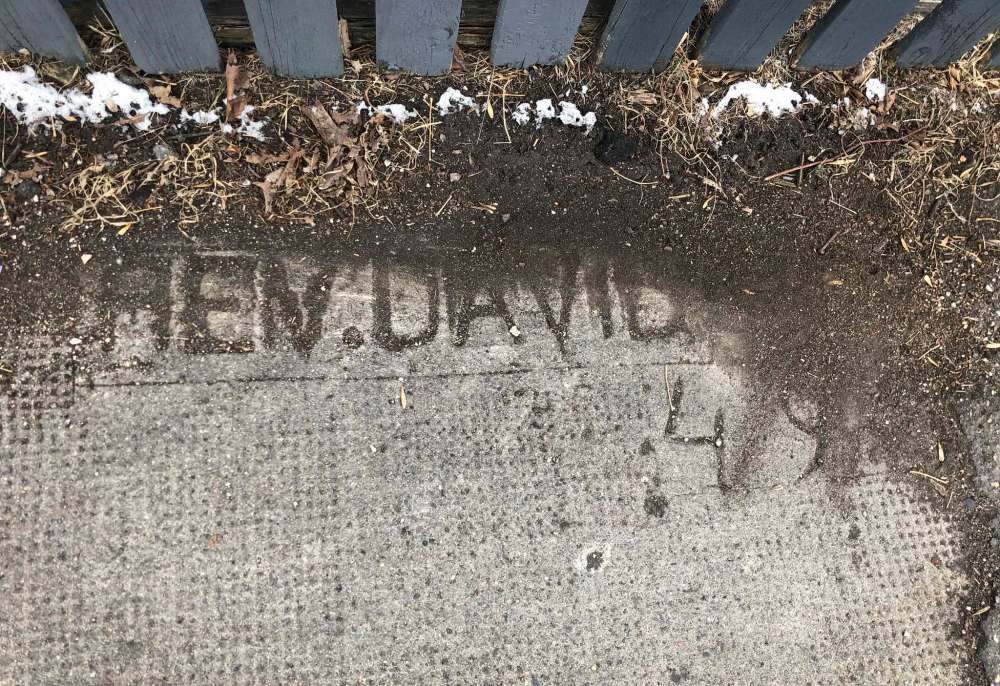

But not before in 1949, when new sidewalk was being poured in front of the home, a city worker — as a sign of respect — wrote “REV. DAVID CANTOR” in the still wet cement.

• • •

The sidewalk hasn’t changed in 72 years, it turns out. Under a thick patch of dirt, “REV. DAVID CANTOR” still can be read.

“I had no idea,” said Hoang, peeking at the tiny bit of history. “That is very, very interesting.”

After the Cantors, the house was subdivided and rented out, usually at relatively low prices. In 1966, it was put up for sale by a Mr. Dudzik, who wished to retire and listed it thusly: “A most unusual house: This distinctive residence, located at 494 College Avenue, is presently a seven-suite apartment block…. The building has many other possibilities… spacious grounds (93 feet of frontage) with 19 rooms.”

Up for private sale again in 1987, a woman named Maria at 582-2141 entitled her advertisement “The Castle,” calling it one of a kind.

Eventually, Vanh Thiep Hoang saw it and fell for it for all those reasons, not even knowing at first the history the building held. Over the past months, with a handyman friend he’s restored the top two floor units, installing hardwood flooring, repainting and restoring the light fixtures.

He says leaving the house is not an easy thing to do, and something he at times doesn’t even want to do. He hopes any person who buys the Castle takes good care of it and understands what a unique opportunity they have to own a piece of history that somehow has remained standing for 115 years.

Who will be the next monarch at the Castle of College Avenue?

ben.waldman@freepress.mb.ca

Ben Waldman covers a little bit of everything for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.