The high price of a plague In contrast to the tax-cutting, debt-averse budget Manitobans got last week, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is likely going to run up a hefty bill to pay for his pandemic-fuelled social and economic rebuild

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 16/04/2021 (1700 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

Big government is having a moment.

As countries come to grips with the ongoing economic fallout of a global pandemic, federal governments here and elsewhere are looking to go big. As in bigger stimulus and recovery packages, bigger deficits, bigger expansion of national programming.

Across the border, President Joe Biden recently unveiled the second-largest stimulus bill in U.S. history and has launched a multitrillion-dollar infrastructure plan in the hopes of getting the economy back on track.

Closer to home, all signs leading into next week’s federal budget point to the Liberal government embracing the same “bigger is better” philosophy.

That’s not the case in Manitoba, though.

Brian Pallister’s provincial government signalled quite clearly when it released its budget last week, that it will continue to pursue small-government ideals of deficit reduction, cost-cutting and trimming taxes — COVID-19 be damned.

● ● ●

When Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government unveils its long-awaited budget Monday — the first in two years —Canadians will get a better idea of what the federal Liberals mean by “building back better.”

The slogan, which Trudeau uttered last year, has not been defined beyond vague platitudes about the need to address social and economic inequalities in a post-pandemic Canada. For fiscal conservatives, the catchphrase is code for “big government” — an excuse to further extend the tentacles of the state into the lives of Canadians. For progressives, it’s an opportunity to “reset” the social and economic fabric of society; to fix long-ignored issues such as poverty, racial discrimination and environmental degradation.

“Building back better” was popularized internationally in the early 2000s as a rallying cry to rebuild communities more equitably following natural disasters. Former U.S. president Bill Clinton used it in 2005 when he was the United Nation’s special envoy following the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.

The idea of making things better, not just reverting back to the status quo, is a theme several world leaders have adopted as countries plan to rebuild following the pandemic.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson has vowed to “build back better” to ensure a “levelling up” of his country once COVID-19 is under control. U.S. President Joe Biden used it as a campaign theme during last year’s presidential race, emblazoning the words on podiums and banners.

“It’s not sufficient to build back, we have to build back better,” Biden said last summer.

The Trudeau government made it the centrepiece of its speech from the throne in September. Government pledged to “build back better to create a stronger, more resilient Canada” during the post-pandemic recovery.“As we build back, we have the choice to build back better and tackle the challenges that constrain far too many Canadians.”– Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland

“Do we come out of this stronger, or paper over the cracks that the crisis has exposed?” the speech asked.

Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland, one of the driving forces behind the proposed reset, used it repeatedly in her fall economic statement.

The pandemic has “laid bare and in many cases deepened the inequalities” between Canadians, the November report said. It described in detail how COVID-induced job losses have disproportionately impacted racialized communities and women.

“As we build back, we have the choice to build back better and tackle the challenges that constrain far too many Canadians,” Freeland wrote.

But what does “building back better” mean, exactly? The government has offered some clues, most of which are rehashes of previous election-campaign commitments.

The 2021 budget will almost certainly include new funding for child care and early learning. It’s unlikely a new stand-alone “national” child-care program will be announced this year. But a down payment and a vision of what a new model could look like is expected.

As usual, the devil will be in the details. Like most social programs that encroach on provincial jurisdiction, there can be no “national” child-care framework without provincial co-operation and consent. Attempts in the past to create any type of national child-care scheme — the Liberal party has been promising one on and off since at least the early 1990s — have failed due to a lack of provincial agreement. Funding and conditions (provinces tend to dislike strings attached to federal dollars) are usually the main stumbling blocks.

A national, universal pharmacare program is also on the list. It’s been featured prominently in Liberal campaign platforms in the past, but remains largely on the back burner. Ottawa set up an advisory council in 2018 to provide advice on how to create a national drug program. So far, only the “foundational elements” have emerged, with a focus on coverage for high-cost drugs and the creation of a federal drug agency to negotiate better prices. A “building back better” budget could push the national pharmacare file forward.While the Liberal party overwhelmingly approved a non-binding motion in favour of a basic income program at its convention last weekend, it appears that will have to wait.

Beyond those two initiatives, there are few details about what the Liberal government has in mind to reshape Canada’s economic and social landscape. There’s been talk of a universal basic income program (guaranteed income to all Canadians regardless of employment status). While the Liberal party overwhelmingly approved a non-binding motion in favour of a basic income program at its convention last weekend, it appears that will have to wait. Trudeau has said repeatedly now is not the time to consider a change of that magnitude.

There will likely be heavy spending in areas such as health care, infrastructure and the environment in the budget. The Liberals have made clear they want a post-pandemic recovery to be “green.” In addition to a $1.5-billion building retrofit program announced by the federal government Wednesday, new money is expected for electric-vehicle charging stations.

Whatever shape the “reset” takes, it will cost money — a lot of it. Considering the federal government is already on the hook for hundreds of billions in new debt — mainly to stave off economic ruin during the pandemic — where those dollars will come from will become a critical part of the debate.

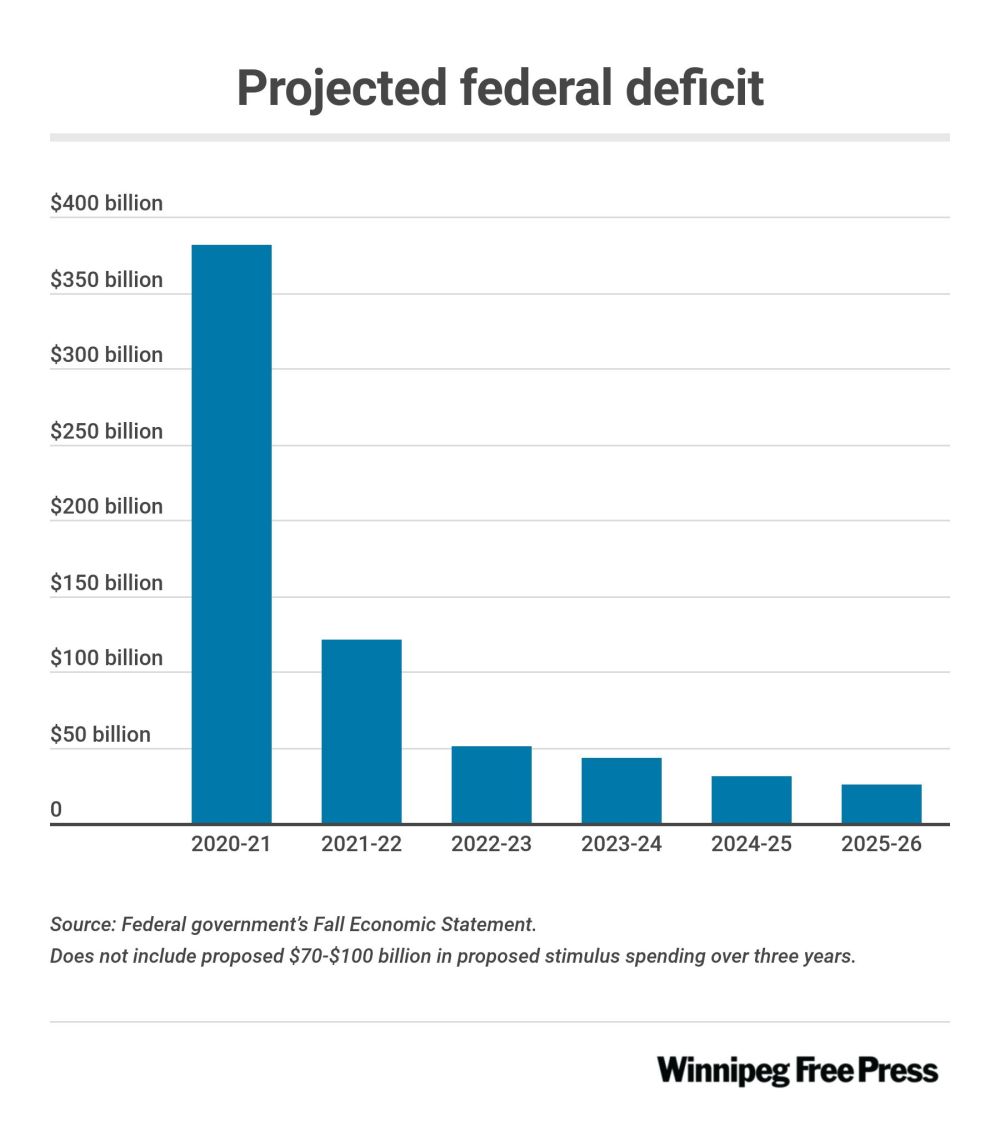

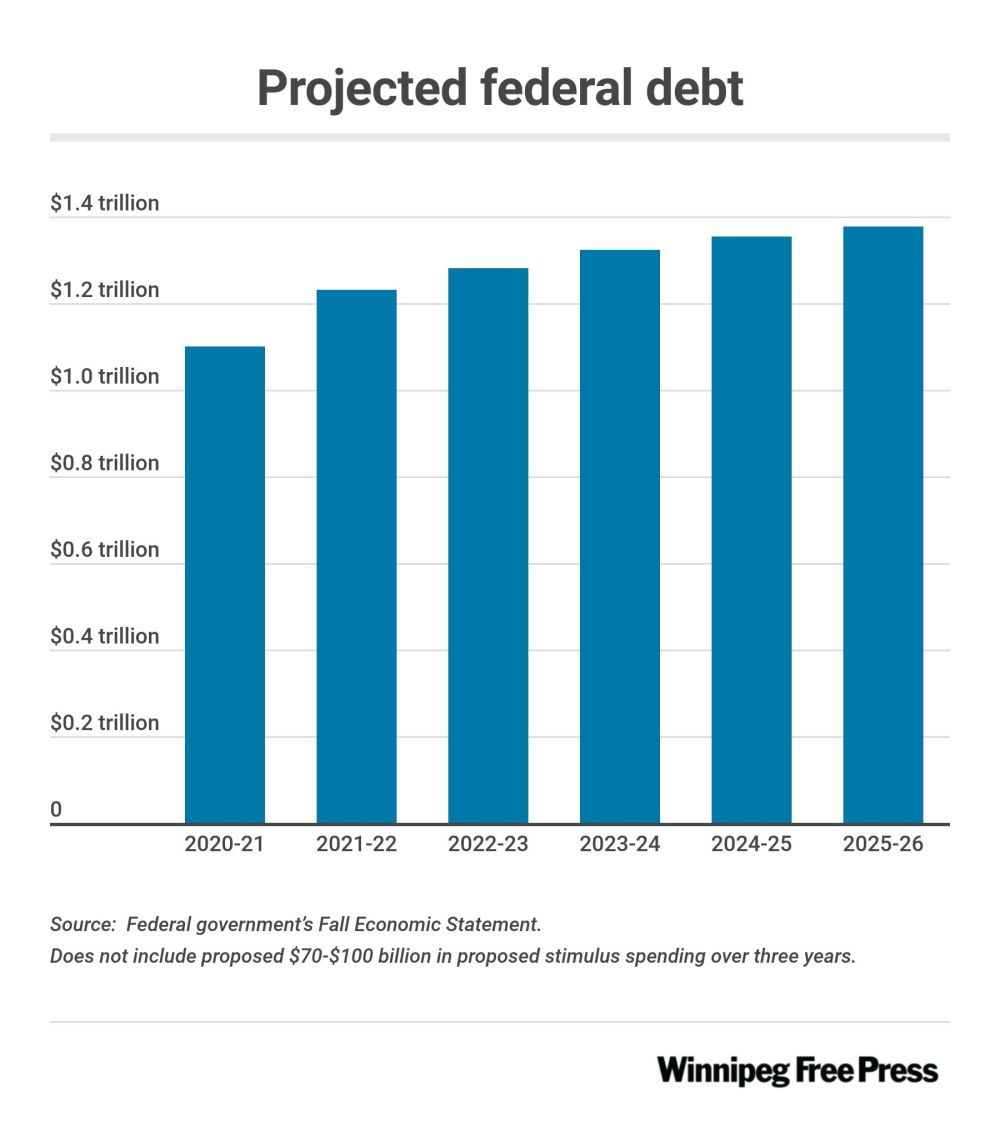

Ottawa is projecting a deficit of $381 billion for 2020-21, about 10 times the size of its shortfall the previous year. (Canada’s parliamentary budget officer predicted a slightly smaller deficit of $363 billion in its March update). The federal debt is projected to balloon to a record $1.1 trillion and is expected to grow for at least five years.

Federal debt as a percentage of the economy — one of the key metrics used by economists to compare government debt from year-to-year — is at historically high levels. It’s expected to hit 50 per cent of GDP in 2021, well above pre-pandemic levels in the low 30-per-cent range. It’s still below the 67-per-cent peak reached in 1995-96, when the federal government was forced to balance the books in then-finance minister Paul Martin’s words, “come hell or high water,” or face the wrath of nervous credit-rating agencies. Still, at 50 per cent — and growing — it’s already making some economists nervous.

The C.D. Howe Institute in a report last week warned of the dangers of rising federal debt. The think tank called on Ottawa to scale back its stimulus spending and temper plans to expand its social agenda.

By the numbers

Freeland, meanwhile, has already committed $70 to $100 billion in stimulus spending over the next three years to kick-start the economy. That’s expected to be a key part of the 2021 budget. Those dollars have not been factored into the Finance Department’s fiscal framework (they will be on budget day). But the department did release some estimates: if the full $100 billion is spent, the debt-to-GDP ratio could climb as high as 59 per cent.

How international credit-rating agencies would view that — and what impact it might have on the federal government’s borrowing costs down the road — is a critical part of the debate.

Federal officials argue borrowing today is more affordable than it was in the 1990s because of historically low interest rates. What’s more, the federal government is rebalancing its debt portfolio to include longer-term debt; in some cases locking in low interest rates for as long as 50 years.

However, not all federal debt is long term. As shorter-term debt matures, Ottawa may be forced to refinance at higher rates, which could drive up servicing costs, some economists have warned.

John McCallum, finance professor at the University of Manitoba’s Asper School of Business, says it’s difficult to predict how markets might react to that level of increased borrowing.

“The markets, in general, have treated this entire experience (the pandemic) as one giant one-off, something in the class of maybe the Second World War,” says McCallum. “The markets have been tolerant of the need to put financial-practice issues aside and get the job done.”

How long that tolerance will last is anybody’s guess, as the global economy remains in uncharted territory, he says.

Government debt has been financed largely by the Bank of Canada. In normal times, the hundreds of billions in bonds bought up by the central bank over the past year from the federal and provincial governments would drive up inflation and interest rates, McCallum says. So far, that hasn’t happened. But those risks remain if government continues to borrow at record levels once the pandemic is over, he said.

“Can you finance the big reset on exactly the same terms (as the pandemic)?” he says. “That’s an open question.”

The cost of not taking action to address social and economic inequalities is more difficult to measure.

The financial consequences of poverty and homelessness in Canada are well documented, as are the pandemic’s impact on women in the job market.

Canada’s uneven playing field between racialized and non-racialized communities is more difficult to quantify in dollars and cents. Nevertheless, those inequalities — and proposed solutions to address them — will undoubtedly be part of this year’s fiscal blueprint.

David Macdonald, senior economist with Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, says the pandemic taught Canadians a lot about the cracks in the country’s social safety net, particularly around long-term care for seniors, child care and unemployment supports.

Macdonald says it’s important the federal government begins to address those areas in this budget.

“Those are certainly things that we can build back better because they weren’t particularly well-built in the first place,” he says. “The performance of long-term care in Canada was one of the worst in the world in terms of death rates.”

Macdonald said he believes “continuously low” interest rates, similar to the experience in Europe, provide Ottawa with the fiscal capacity to fund new initiatives over the long term.

“I think that is our future, as opposed to rising interest rates,” he says.

With a federal election expected as early as this year, the proposed reset could happen sooner rather than later. How far — and how fast — the federal government proposes to “build back better” are the only questions left to be answered.

●●●

If not for COVID-19, Brian Pallister would have been doing a happy dance last March as the 2019-2020 fiscal year drew to a close.

Although the public would not know it until months later, the Progressive Conservative premier was set to achieve one of his biggest political goals — eliminating the provincial deficit, which had ballooned to nearly a billion dollars under the previous NDP government.

But last spring Pallister would also have known that his government’s accomplishment would be short-lived. The pandemic was about to sink the province into a sea of red ink.

For a man who had spent the previous four years making it his objective to rein in provincial spending and reduce the size of government, that must have hurt.

“Have you ever cleaned your hallway and then your kid comes in and tracks mud everywhere?” asks Shiu-Yik Au, assistant professor of finance at University of Manitoba’s Asper School of Business. “That’s the experience.”

While the PC government spent close to $2 billion more in the past fiscal year than it did the previous year — an increase of roughly 10 per cent — that doesn’t mean that it’s ready to abandon its small-government approach.

It’s not in Pallister’s DNA.

Recently, the Tories announced plans once again to bring the province’s books into balance. They’ve given themselves eight years to accomplish the task, although, with the April 7 budget, they’re on pace to accomplish the daunting task in five years.

According to the latest estimates, Manitoba incurred a $2.08-billion deficit for the fiscal year ended March 31. The new budget projects the current year’s deficit at $1.597 billion.

One sign that the government is determined to balance the books as soon as possible is its peculiar decision to create a separate budget category for pandemic spending rather than assigning those expenditures to specific departments.

The clear message is that the additional COVID-19 spending is temporary and is not going to be built into future departmental budgets.

The province estimates that it spent $1.977 billion on COVID-19-related expenses in 2020-2021. For the current year, it forecasts $1.18 billion for such costs.

The government expects that all other budget spending in the coming year will rise by just 1.64 per cent.

The fact that the budget also calls for $200 million in tax cuts (with more to come next year), while shrinking the deficit, shows just how determined the Progressive Conservatives are to pursue a small-government agenda for years to come.

●●●

In its first four years in office, the Pallister government reduced the size of the civil service by 2,500 positions. There were 12,371 civil servants on March 31, 2020 compared with 14,876 on the same date in 2016.

The 2021 figure won’t be released until fall, but there’s no sign the province hired more government workers to meet the challenge of responding to the pandemic.

Rather, the PCs contracted with the private sector and non-government institutions to deliver some programs.

For example, to help businesses and non-profits access federal COVID-19 support programs, the province hired a local private company — 24-7 Intouch — to do the job at a cost of $2.9 million. Concerned about the effects of the pandemic on Manitobans’ mental health, it signed a deal worth $4.5 million to have corporate human-resources giant Morneau Shepell deliver services to those struggling to cope. The government brought in private security firm G4S Canada in November, at a cost of up to $1 million, to help enforce public-health orders. And it even enlisted the Manitoba Chambers of Commerce and the Winnipeg Chamber of Commerce to help it deliver child-care services grants.

Early on, the government was roundly criticized for its tepid economic response to the pandemic — even by business and economists, such as the U of M’s Au, who is a member of both the federal and provincial Conservative parties.

“In this time of fear and uncertainty, we need the government of Manitoba to spend more money,” Au wrote a year ago in response to provincial austerity measures at a time when the private sector was struggling. “Governments can break the vicious cycle of reduced spending and income by leaning into the wind and spending more in times of crisis.”

At the time, the government was considering significant public-sector cuts to free up more money for health, including personal protective equipment. Au and other economists saw public-sector spending cuts as endangering an already weakened economy.

At a time of economic uncertainty due to the lasting effects of the pandemic, the government undertook a plan to eliminate the deficit in eight years while announcing large tax cuts that disproportionately benefit wealthier Manitobans.

Pallister eventually yielded to public pressure and opened the provincial treasury, boosting supports for business, joining forces with Ottawa to enhance the wages of front-line workers and, controversially, issuing a $200 cheque to every Manitoba senior.

“Wisely, (the PCs) backed off those cuts and moved towards — eventually — a model of more spending. It just took longer than some other people would have suggested,” Au says.

But all indications are that the Pallister Conservatives are going to revert to form as soon as they can. While the federal government is shovelling out gobs of cash to prop up the economy, Manitoba appears more preoccupied with getting its fiscal house in order.

Large long-term public investments being championed in some quarters appear to be falling on deaf ears.

These investments would include boosts to public health (broadening medicare to include mental health treatment, dental and elder care), child care, social housing and the green economy.

The left-leaning Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives says the current economic crisis brought on by COVID-19 provides an opportunity for governments to transform social and economic institutions to address economic inequality and make investments to tackle the climate crisis.

“The needed effort and response to the coronavirus pandemic has been compared to that (following) the Second World War, a traumatic global event that ushered in a historic reduction in economic inequality and decades of relative stability, growth and improvements in living standards for working people,” states a recent report by the CCPA’s Lynne Fernandez and Jesse Hajer, a U of M professor.

“Since the 1970s, however, crises have more often been exploited by the wealthy and corporate interests to further profit at the expense of the broader population,” they write. “How we collectively respond to the COVID-19 crisis, and whose interests are prioritized, will have immediate and lasting impacts on who recovers and who bears the cost of this emergency.”

In an interview, Hajer says the recent provincial budget confirms the Progressive Conservatives’ small-government approach.

At a time of economic uncertainty due to the lasting effects of the pandemic, the government undertook a plan to eliminate the deficit in eight years while announcing large tax cuts that disproportionately benefit wealthier Manitobans. The main tax cut will reduce education property taxes by 50 per cent over two years. The PCs had previously promised to eliminate that tax over a 10-year period.

“Engaging in these tax cuts, to me, signals we’re still on the same path where we’re somehow going to cut taxes and stay focused on balancing the budget,” Hajer says. “Well, the only way to do that is to restrain (spending) significantly and constrict services. That seems to be the message coming out of the budget.”

There are commitments in the provincial budget to spend some money to address the COVID-19 crisis, but it’s unclear whether all of those dollars are going to be spent, the economics professor says.

“The trajectory in the past has been to budget and underspend, and I would suspect that is going to continue,” he says, adding that constraining needed expenditures, particularly in education and social services, is going to cost Manitobans down the road and lead to greater economic and social inequality.

“I think it means we’re going to have a slower economic recovery than we would have otherwise.”

tom.brodbeck@freepress.mb.ca

larry.kusch@freepress.mb.ca

Tom has been covering Manitoba politics since the early 1990s and joined the Winnipeg Free Press news team in 2019.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.

History

Updated on Monday, April 19, 2021 9:49 AM CDT: Updates Shiu-Yik Au's job title as assistant professor.