Critical condition Winnipeg’s intensive care program was among the first and most respected in the country; now, burnout, staff shortages and COVID-19 are threatening that legacy

Read this article for free:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Monthly Digital Subscription

$0 for the first 4 weeks*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*No charge for 4 weeks then price increases to the regular rate of $19.00 plus GST every four weeks. Offer available to new and qualified returning subscribers only. Cancel any time.

Monthly Digital Subscription

$4.75/week*

- Enjoy unlimited reading on winnipegfreepress.com

- Read the E-Edition, our digital replica newspaper

- Access News Break, our award-winning app

- Play interactive puzzles

*Billed as $19 plus GST every four weeks. Cancel any time.

To continue reading, please subscribe:

Add Free Press access to your Brandon Sun subscription for only an additional

$1 for the first 4 weeks*

*Your next subscription payment will increase by $1.00 and you will be charged $16.99 plus GST for four weeks. After four weeks, your payment will increase to $23.99 plus GST every four weeks.

Read unlimited articles for free today:

or

Already have an account? Log in here »

Hey there, time traveller!

This article was published 26/03/2021 (1716 days ago), so information in it may no longer be current.

After taking a seven-week online training course, she walked into an overflowing intensive care unit at Winnipeg’s largest hospital to start her first shift as a critical-care nurse.

It was early winter, just past the peak of Manitoba’s second-wave pandemic hospitalizations, and despite her best preparations, she had no real warning about what awaited her inside the ICU.

She was already an experienced nurse, but brand new to critical care. Almost every patient in the ICU that day had COVID-19, and all of them were extremely ill. The equipment designed to keep them alive looked to her like something out of a movie.

All of the ventilators, heart monitors and intravenous lines delivering delicate infusions of sedatives and blood-pressure medications required her interpretation and minute-to-minute reaction. A stable blood-pressure level can plunge in seconds and cause permanent organ damage if left unchecked for mere minutes, and it was now her responsibility to make sure that didn’t happen.

She and the rest of the new critical care nurses had been promised two months of on-the-job training under the watchful eyes of senior nurses and preceptors before they’d be called upon to look after a near-death patient on their own. But the nurses they needed to learn from had double or triple their usual workloads.

“I felt like it was a huge jump from sitting at a computer to ‘go be a nurse.’ I felt like they could have transitioned us a bit better.”

As a new graduate of Manitoba’s critical-care nursing orientation program, she is among the most recent group of nurses to seek the kind of advanced training that first put Winnipeg at the leading edge of intensive care in Canada.

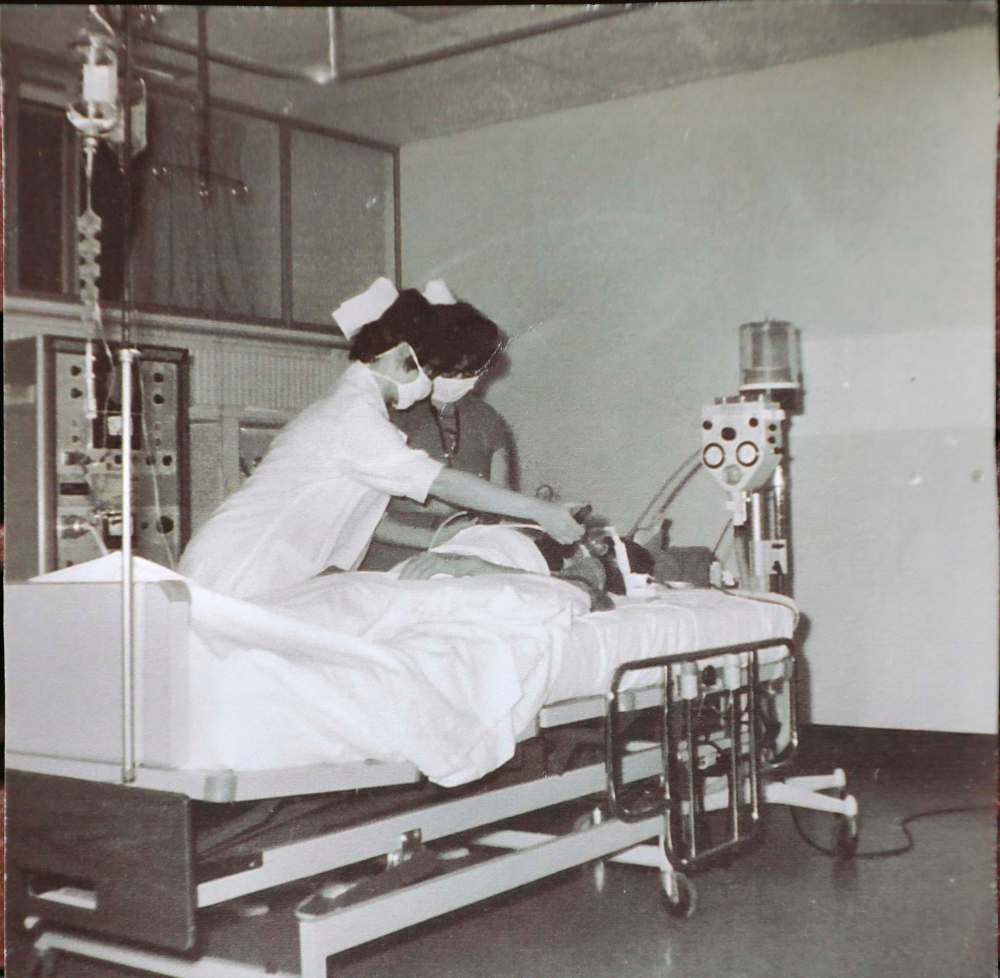

Pioneering local nurses shaped the future of critical care when they underwent the first-ever formal ICU nursing program in Canada at the Winnipeg General Hospital 55 years ago.

The current state of the training didn’t live up to that reputation, says the nurse, who agreed to be interviewed only on the condition of anonymity for fear of losing her job.

“When you became a critical care nurse in the past, you were very well academically trained,” she says. “You could argue that it was a comparable training to a medical doctor, and I would say now it’s like, imagine doing an online quiz. And now you’re a critical care nurse.

“I don’t know what the future looks like for when our experienced nurses eventually retire,” she adds. “And I don’t know what that means for the people who live in this province. The long-term effects are scary to me.”

”When you became a critical care nurse in the past, you were very well academically trained. You could argue that it was a comparable training to a medical doctor, and I would say now it’s like, imagine doing an online quiz. And now you’re a critical care nurse.” – Recent graduate of the critical-care nursing orientation program

The nurse already had years of experience in another field of nursing before she signed up to work on the front lines with the sickest patients, hoping to help out during the pandemic. But her previous position was low stakes compared to the ICU.

If she needed urgent help with a patient then, she could call in a code blue and a team of critical-care nurses would rush in and take over. Now, she was part of that specially trained team, except there wasn’t enough time to learn before becoming responsible for keeping the sickest patients alive.

“It was kind of like, well, I guess we’re just all going to sink in this ship together. And the staff were really great, and the educators tried, but it was just really a lack of planning and a lack of resources, was kind of the reality that I walked into,” she says.

“I didn’t feel as though there was a lot of communication about how COVID was going to impact our learning process, or whether it should have at all.”

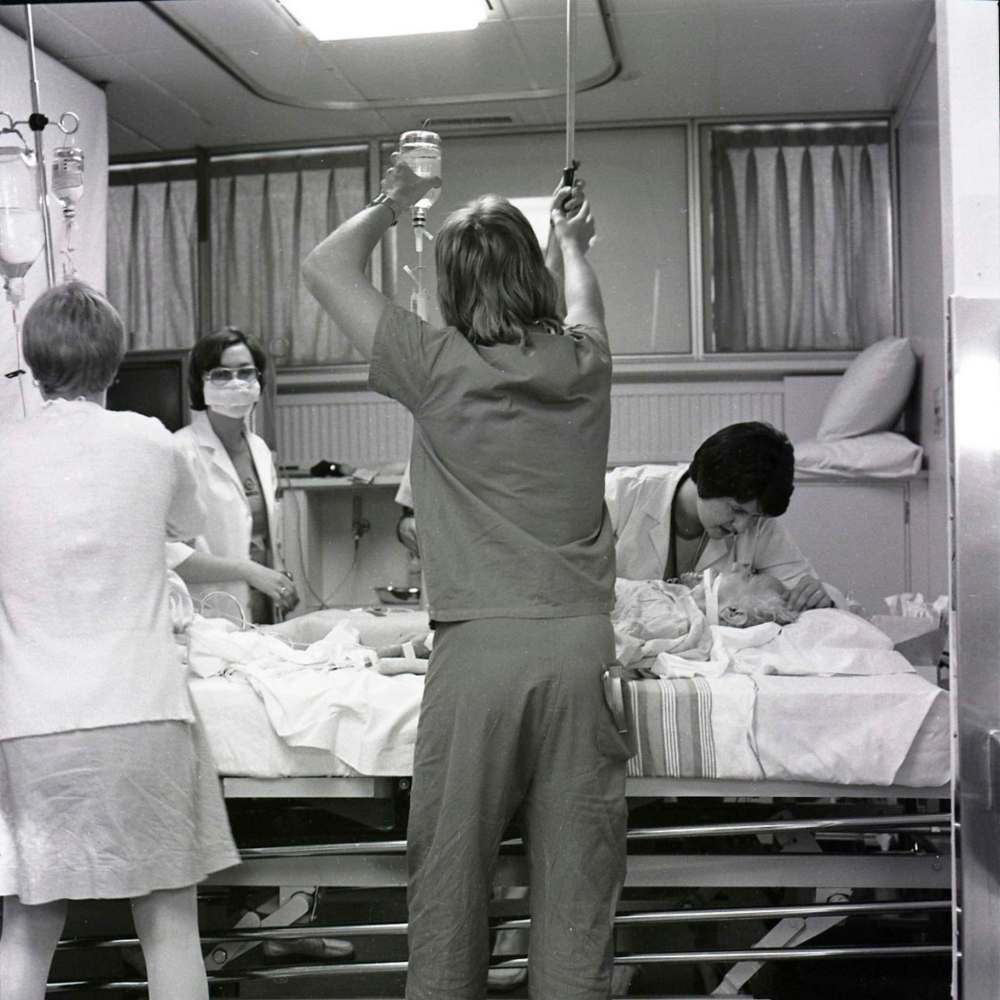

Within her first few weeks in the ICU, the Health Sciences Centre nurse had already dealt with the kinds of extreme conditions she was taught she might expect after a full year or longer on the job. Early on, she was assigned to look after two patients at once — double the usual workload of even an experienced ICU nurse. That happened regularly over the winter.

Some nurses were forced to take on three patients at a time — a move decried as dangerous for patients, according to experienced ICU nurses who spoke to the Free Press.

“I have that same concern when I am doubled (up on patients) because obviously I can’t physically be there to give people basic care or have eyes on them. That’s a form of neglect. But even just as a new person, my concern is that if I don’t have the training and I miss something that I was unaware of, I’m concerned that I’m not upholding the standard,” she says.

“When I’m going to go to work, I’m not a religious person, but I just pray every day, I’m like, please don’t be doubled. Because if I’m not doubled, I can have a good day, even if my patient’s really sick.”

She says she’s making it through, one shift at a time, by leaning on her supportive co-workers. The bedside nurses working alongside her are part of a long history of intensive care nursing in Manitoba.

● ● ●

The first ICU teams weren’t working in the middle of a pandemic, but they were forging a new way forward in the wake of the 1950s polio epidemic.

Those teams were first to make the daily group rounds (currently happening in a socially distanced format) that ICU care still revolves around.

Armed with the special training they got in the classroom and on the hospital floor, Winnipeg nurses and physicians influenced future ICU specialists across the country. They laid the foundation for the intensive care system that is now dealing with its highest volumes of the sickest patients in generations.

As intensive care staff prepare for a potential third wave of COVID-19 in the province, some of those who lived through the early days of the ICU say its history could shed light on the future of critical care — and the critical importance of properly supporting health-care workers on the front lines.

• • •

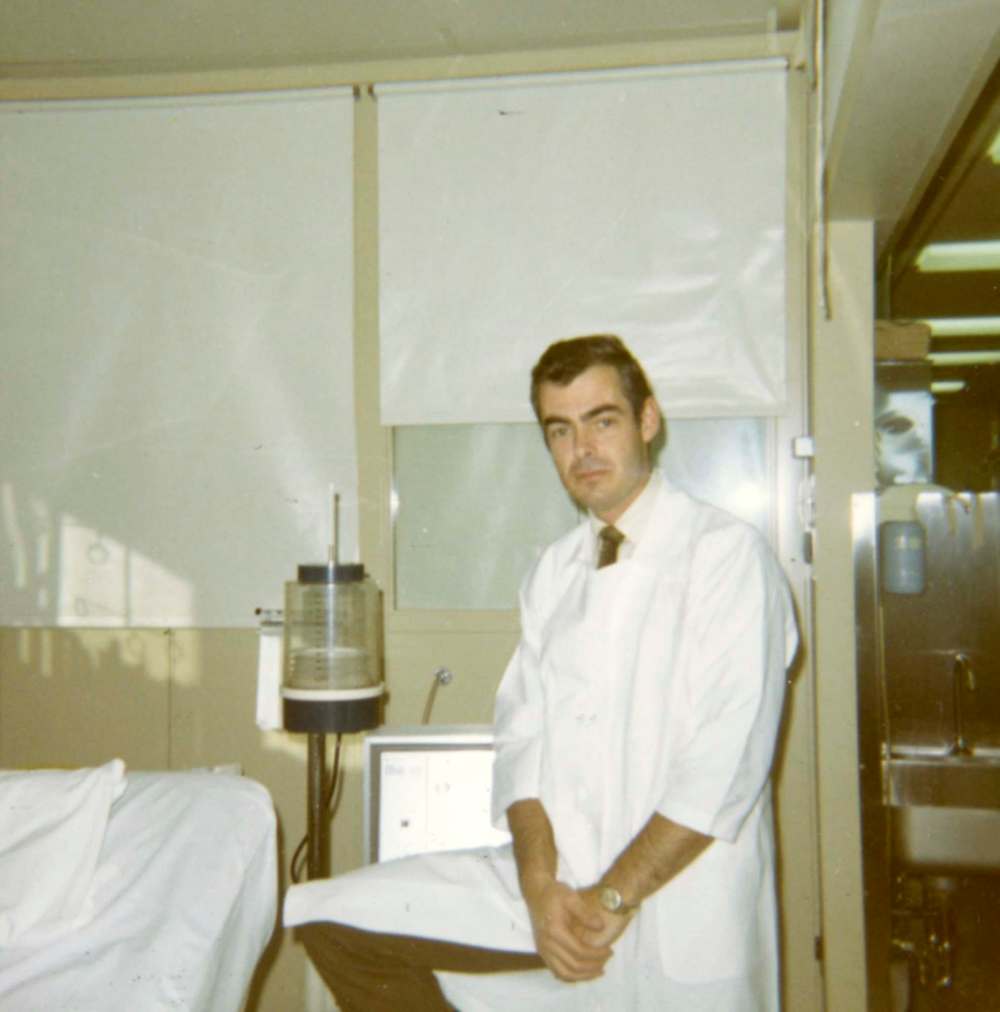

After he spent more than 40 years working in intensive care, much of that time leading the city’s first ICU unit, it took the COVID-19 pandemic to finally give Dr. Bryan Kirk time to start writing a book about its history.

“When I get to the point where this mess of paper on my desk develops some sort of cohesion, I’ll start thinking about where to get it published,” he says when reached by phone at his home in Winnipeg.

The retired physician, now in his 80s, has been described by some of his colleagues as one of the founding fathers of intensive care in Canada, but he is quick to dismiss any such title. He took over leadership of the ICU shortly after it was founded by Dr. Reuben Cherniack, who had visited more advanced hospitals in the U.S. and Europe before returning to Manitoba to carry out his vision for intensive care.

Cherniack, who died in 2016, was building on the work of Dr. Jack Hildes, who had been in charge of treating polio patients at the former King George Hospital.

“We all had the same philosophy, that there needed to be a really good place to look after critically ill patients, and that nursing was critical. I mean, it was the key,” Kirk says when asked about his vision for the ICU.

“You obviously had to have doctors who knew what they were doing, but the bedside nursing was absolutely critical.”

The polio epidemic sparked the creation of intensive care units in hospitals all around the world, all around the same time. But it was no coincidence, Kirk says, that Winnipeg emerged as an early leader.

For one thing, polio ravaged the province. There were more Manitobans paralyzed by the disease per capita in 1953 than anywhere else in North America, Kirk says, and more than 90 patients in iron lungs at King George Hospital at the height of the epidemic. Some of those patients needed to be transitioned to new types of treatment — the first ventilators — and there had to be space for them and other seriously ill patients to recover.

At the time, the local medical research community was “vibrant,” teeming with expert academics and doctors recruited from elsewhere who were eager to take on the challenge.

Winnipeg’s first ICU had been in development since the early 1960s, and it officially opened in 1966 as a 22-bed unit in what is now the Health Sciences Centre. A Toronto hospital lays claim to an ICU opening date of 1962, but Kirk does not engage in this sort of debate.

“In those days, Toronto always considered themselves to be first in everything,” he says dryly.

Whichever was first, he says it’s clear Winnipeg’s ICU dominated the Canadian critical-care landscape, with Edmonton’s unit not far behind.

That Winnipeg started out as the premier place to train ICU nurses is not in dispute. At Cherniack’s insistence, the hospital recognized the need for highly trained intensive care nurses at the same time the ICU was being designed.

Many of the earliest ICU patients were recovering from complex surgery, or cardiac arrests, pneumonia, septic shock and drug overdoses.

“We’d get a lot of overdoses — people were still taking barbiturates then,” Kirk says.

When Kirk was still an intern and later a resident doctor, before the ICU officially opened and before the first specialized nurses were trained, he would stop in at the nurse shift change every morning and night to check on those seriously ill patients hooked up to monitoring devices. He gave nurses “a mini bedside orientation” to explain how the machines worked.

”No alarms are as good as… nurses’ eyeballs.–Dr. Bryan Kirk”

Cherniack implemented a rule that Kirk enforced in the decades that followed: one patient per nurse. The only time a nurse should have two patients was when they both were not as sick as the rest.

“The rule was, if a patient was on a ventilator, there was a bedside nurse assigned to that patient,” Kirk says. “The patient can get disconnected, all sorts of bad things can happen, and no alarms are as good as… nurses’ eyeballs.”

• • •

There was still an iron lung in a room down the hall when nurse Eleanor Cramp started working on the second floor of the Winnipeg General Hospital in the early 1960s. Not yet equipped with ventilators, it was a five-bed unit that would become one of the first spaces for intensive care patients in Canada — patients who, not long earlier, would likely have died because there was nothing doctors could do for them.

The specialty was “evolving before our eyes,” Cramp says.

She was part of the inaugural class of around 24 specialized ICU nurses starting in 1966 — a yearlong post-graduate program recognized as the first of its kind in Canada and among the first in North America. The same year, the first ICU opened, expanding from that initial five-bed space to a 22-bed area on the seventh floor of the hospital.

“They called us pioneer nurses or pioneer staff of that era,” she says.

For the first time, nurses with previous hospital caregiving experience began to monitor extremely sick patients at the bedside, administering medications and learning how the heart monitors and breathing machines worked.

They studied versions of the anatomy and physiology lessons that doctors learned in their first two years of medical school, and their early classes featured in-hospital biomedical engineering lectures on new technologies.

The idea was that ICU nurses should be intensively trained on all body systems — including the lungs, the heart, the kidneys and the brain — and be adept at what they called the “art of nursing,” offering compassionate care to immobilized patients.

The course combined in-class lessons and first-hand clinical training under the buddy system, which set the benchmark for all future ICU nurses. Manitoba ICU nurses completed fundamentally the same program until 2008, and in the early years, nurses from across Canada travelled to Winnipeg to train in intensive care before similar hospital-based courses got underway in other cities.

“We had so many deaths at the start. Everybody was dying. And you worked so hard. They were the worst of the worst, you know, very sick people coming in, and it was a wonder anybody got better, really,” Cramp recalls.

“But a lot did, and they would come back and come see the intensive care (unit after they recovered),” says Cramp, who spent six years working in the ICU, four as head nurse.

Despite being around so much death, Cramp says the life-saving power of the work and the camaraderie with other nurses made it life-changing.

“You never expect they’re going to die… You’re going to be the one that gets them better.”–Eleanor Cramp

“You never expect they’re going to die,” she says. “You’re going to be the one that gets them better. That’s why they’re in the ICU, to get better.

“To have been part of that, to have learned and to have contributed, was a fantastic experience in my life.”

Staffing was a challenge from the start — there were too few nurses who qualified to work in the ICU. Cramp recalls one shift working with a registered nurse who was tasked with temporarily filling in. The other woman went on a break and didn’t return.

“She left the room — I guess we thought she was going to the bathroom — but she never came back. She was just not qualified to do it and it terrified her.”

And from the beginning, teamwork was the only way ICU nurses made it through.

“We were extremely busy. We worked as a team. We would often have only one patient or two patients, and no one would leave until everybody was ready to go,” Cramp recalls.

While she worked late nights, her soon-to-be husband and future director of respiratory at the Health Sciences Centre would wait for her in the hallway. Harvey Cramp remembers observing exhausted nurses and doctors rushing in and out of the unit.

“I sat and watched a doctor one night working at the desk, and he was writing. He’d written off the chart and was writing (directly) on the desk. He was so tired. That’s how they worked,” Harvey Cramp says.

During those late nights, he’d get glimpses of the ICU staff working with new devices that intrigued him. His observational eye and mechanical nature led him to become a respiratory technician. He worked on the first ICU “Bird” ventilators, manually adjusting air flow, and spent decades trying to develop new ways to help people with respiratory problems.

Both 81 now, the couple received their first doses of the COVID-19 vaccine earlier this month. They say they have great empathy for the health-care workers responding to this virus — particularly the ICU nurses.

“They’re the heroes of this pandemic. Clearly, they are. And they’re unrecognized,” Eleanor says.

• • •

HSC made space for more than 30 ICU beds at the height of COVID-19’s second wave, with 19 nurses to staff them. Other nurses, some of whom didn’t have any critical-care experience, were brought in as “extenders” to fill the gaps.

That backfired, ICU nurses say, because the extender staff didn’t have the specialized training needed to work in the ICU, and couldn’t step in to help when so much of the minute-to-minute work in the unit can mean life or death. Even something as seemingly simple as turning a patient to avoid bedsores had to be done by a nurse who knew how to navigate the equipment and manage resulting drops in blood pressure.

Only in the past month, as hospitalization rates steadied, was a working group struck so medical ICU nurses could share their input with management.

1.jpg?w=1000)

Two nurses who spoke to the Free Press said the committee was finally formed after some nurses quit and other experienced ICU nurses threatened to leave after being stretched too thin, to the detriment of their patients. It comes in the wake of news coverage that exposed the emotional and psychological toll the pandemic response is taking on ICU nurses.

The nurses said they’ve long felt ignored by health-care decision-makers, even before the pandemic began. They said they feel like “worker bees” or even “cattle.”

They have serious concerns about the safety of their patients when they’re tasked with juggling too many, and they bristle at being reminded this is an unprecedented time — they don’t need to be told. They’re living it.

“Sometimes you don’t pee in 12 hours, or have a drink. And I can’t tell you how much you sweat in some of those gowns that are essentially plastic bags that you’re wearing. But we suck up those things because this is the unprecedented time. You can suck up anything for a day for the greater good of your patients and your team. You cannot suck it up constantly,” says one experienced ICU nurse.

She, like many in the field who were interviewed by the Free Press, noted the gender disparity in the profession as she questioned why staff who were untrained in the specialty were sent to fill in. Unlike some other specialized professions, she says, “we are a group of women.”

The unit she works in now, she says, is unlike the one she trained in years ago.

“It’s funny that you should think that a mood in an intensive care should be anything less than doom and gloom and tears, but that’s not our unit (normally). And right now I would use the phrase ‘We’re a broken unit.’ People are hurting.”

At the start of her career, she didn’t have to wonder whether someone would be able to help her as she worked to keep patients alive.

”Now, every day, you just never know. How many patients you’ll have, if you’ll have a bad situation, if you’ll be supported, if you’ll have help.”–Veteran ICU nurse

“Now, every day, you just never know. How many patients you’ll have, if you’ll have a bad situation, if you’ll be supported, if you’ll have help,” she says.

“I didn’t worry about that in the early days, even as a new person in the ICU. I wasn’t afraid. I knew someone would help me if I needed it. And that’s the difference.”

She says she worries about the post-pandemic future of the profession.

“It gets harder when you yourself are becoming disillusioned and the new people are like, ‘What did I sign up for? I want to go back to where I came from.’ Which is their choice, right? No one has to stay once this is over.”

• • •

Manitoba ICU nurses’ training programs have been shortened and sped up over the decades — usually in sync with nursing shortages — even as medical technology has advanced and patients have landed in intensive care with increasingly complex conditions.

Alice Dyna remembers the pressure she faced as an educator in the ICU program during nursing shortages. She was an educator for 35 years before retiring in 2011, and invariably over the years, budgets would be tightened and the powers-that-be would want to rush the training to get more nurses on the job.

Winnipeg’s contribution to critical care

The burden on Manitoba’s intensive care system has never been greater than during the current COVID-19 pandemic.

When Winnipeg’s first ICU opened 55 years ago, it was not designed for any kind of pandemic. A lot has changed in intensive care since then, but the fundamentals are the same.

The burden on Manitoba’s intensive care system has never been greater than during the current COVID-19 pandemic.

When Winnipeg’s first ICU opened 55 years ago, it was not designed for any kind of pandemic. A lot has changed in intensive care since then, but the fundamentals are the same.

It was always intended as a place where the most desperately ill patients — many of whom were brought back from the dead — could get a chance to recover under constant supervision, by relying on up-to-date technology to keep their hearts pumping and their lungs breathing.

Technological advancements, better data collection, and the occasional system-wide shuffle — amid near-constant staffing concerns — shaped it into the system that is now shouldering more of the sickest patients than ever.

Past and present leaders of intensive care programs in Manitoba weighed in on how they contributed to the existing state of intensive care.

Understanding the evolution of critical care, and the role Winnipeg played in pushing it forward, is important even in this crisis, says Dr. Bojan Paunovic, the provincial lead of critical care for Shared Health and the president of the Canadian Critical Care Society.

“For me, it’s a matter of pride to be attached to an area that has this history and can (demonstrate) how well critical care has developed in this city and continues to meet the challenges of different demands,” he says. One of those points of pride, for him, is that Manitoba handled twice as many ICU patients, per capita, than Ontario did at the peak of our second wave in December. There were more than 70 Manitobans in intensive care with COVID-19 at that time.

“Our per capita ability to accommodate (ICU patients) this second wave, with a lot of help from other areas of the system, in ICUs in Winnipeg and in Manitoba… I think that could be seen as a testament of all that groundwork that occurred decades ago and continues to happen now.”

Once at the forefront of specialty training for nurses and doctors, the ICU at Winnipeg’s largest hospital went from a five-bed room to a 22-bed official unit on the seventh floor of the Winnipeg General Hospital.

Its founders had the foresight to install six isolation rooms for contagious patients, but those rooms went mostly unused for years, dismissed by some as an expensive design flaw that took up too much space, says Dr. Bryan Kirk, who worked in ICU for more than 40 years and led the unit until the early 1980s.

Kirk was seen as an innovator in the newly emerging field. He was the first president of the Canadian Critical Care Society and was occasionally asked to speak about the Winnipeg ICU’s successes at international conferences. He supported specialized training for ICU doctors and nurses at a time when few similar programs existed in Canada.

Agreeing to lead the brand-new unit was the best thing he’s done in his career, he says. “Couldn’t have had a better career anywhere else. A lot of other places, people just didn’t understand what it (intensive care) was all about.

“Winnipeg was so far ahead that it seemed like a natural thing.”

Under Kirk’s watch, multidisciplinary teams of doctors, nurses, pharmacists, respirologists, physiotherapists, dietitians and other professionals took an active role in intensive care and participated in daily rounds. To replace medicine carts and keep improved drug data, Kirk established the first satellite pharmacy in the ICU so staff would have the right medication at their fingertips, urgently. He and his team worked with manufacturers to develop monitoring devices and respiratory technology that was often tested and implemented in Winnipeg before being put into use in other hospitals.

The ICU was split into multiple units, with specialties in surgical and cardiac care. Teams also created “step-down” units for people in recovery who didn’t necessarily need an ICU bed but were still seriously ill.

The number of beds fluctuated over the years, and some had to be closed due to recurring nursing shortages — a repeating pattern.

Dr. Dan Roberts took over as Kirk’s chosen successor in the midst of one of those shortages in the 1990s.

“At that time, I had a plan. I saw a lot of problems with intensive care and the way it was being delivered in the city, the lack of co-ordination and waste. And I envisaged a fairly straightforward new way of doing business,” Roberts says.

As regional health authorities were being established in the province, he made dramatic changes that centralized the 11 different ICUs that existed in Winnipeg at the time and tried to standardize the level of care they offered, requiring ICU doctors anywhere in the province to pass an exam in order to continue practising in intensive care — “It was a bold thing to do,” he admits.

One of his key battles — the results of which have been amplified during this pandemic — was an attempt to make ICU beds more accessible to critically ill patients who lived outside Winnipeg. He saw in the ‘80s and ‘90s that it was often so difficult for community doctors to secure spots for their seriously ill patients, and there was no requirement for hospitals to provide an ICU bed for outside patients rather than reserving it for their own.

“(Community physicians) would phone one hospital after another to see if there was an intensive care unit bed there,” Roberts says. “They would often just get told, ‘call somebody else.’… And so there was nobody that was designated to take the responsibility of saying, you know, when sick patients outside of your hospital need an intensive care unit bed, you have to be part of the solution.”

Under his direction, a central ICU bed registry was set up. All ICUs had to report the status of all beds, and an on-call doctor handled requests from across the province. Later in the 1990s, a Winnipeg critical care transport team was established to shuffle ICU patients to different hospitals, depending on their specific needs.

“In planning for this pandemic, that very highly organized system was already basically burned into critical care,” Roberts says. “And the physicians who train here have that sense of obligation, because they’re trained in that system.”

The data-collection system he started to track patient outcomes and inform advanced research is being carried on by other intensive care doctors and researchers, Roberts says.

“A lot of the young physicians in intensive care now are intimately involved with that. They’re very enthusiastic about it; this has been going on now more than 10 years. So that’s something that I started to do in the late ‘80s, and it took a long time for other physicians to get interested in it.”

The province’s major consolidation of Manitoba’s health-care system in 2019 cut the number of Winnipeg acute-care hospitals in half, from six to three, and that overhaul was not yet finished when the pandemic hit. Pre-pandemic, there were 72 ICU beds, all of them in Winnipeg and Brandon. Extra units have had to open up in other hospital areas to meet the demand.

As Manitoba’s current leader of critical care, Paunovic says systemic staffing challenges will need to be addressed to maintain the future of ICUs — and not just critical care, but the health-care system as a whole.

“It’s human resources across the board. How are we going to be able to accommodate future surges without making major impacts on things like surgeries, like elective surgeries that got pushed off? To me, that’s the main issue, not just in ICU but globally,” he says.

“How are we doing to ensure there’s people available to look after people?”

— Katie May

But Dyna, who lived and breathed the intensive care program herself in the early days, saw it as her mission to uphold the highest quality of ICU training.

She wanted nurses who were the strongest critical thinkers, who had the scientific knowledge and self-confidence to know what to do at any moment and do it well, whether they were brushing a patient’s hair, or helping to medically bring them back from the dead.

And if they didn’t know what to do, they’d know how to turn to their team for help.

“There were times where I guess I just had to stand up to people and say, no, that isn’t right. I’m not passing that person just so that they can go on, because they haven’t met the level that we expect of them,” she remembers.

“Sometimes I felt like all they wanted was a warm body there, so they could say that they had a nurse at the bedside, whether that nurse was able to look after the patient appropriately or not. And I hated that feeling.”

“Sometimes I felt like all they wanted was a warm body there, so they could say that they had a nurse at the bedside, whether that nurse was able to look after the patient appropriately or not.”–Alice Dyna

Getting an ICU nurse to stay two years was, at one time, considered an accomplishment. The pandemic intensifies burnout concerns that have been aired since the beginning, and Dyna admits she’s worried about the future of critical-care nursing.

“There’s always, I think, been a shortage of ICU nurses, and that’s because we tend to burn them out with the conditions that they have to work under.”

Leaders like Dr. Kirk knew how to give nurses a voice, and she says she wants that legacy to continue.

“The worst thing that you can do to somebody, especially when you’re relying on their expertise, is to silence them. You need to create an atmosphere where they are able to express the knowledge that they have, and if you silence them then you’re the one who’s missing out on that type of information.”

By the time she retired a decade ago, Dyna says, nurses weren’t being listened to: “They were expected to be more silent.”

ICU nurses are still mostly women; there were no male graduates of Winnipeg’s ICU nursing program until the early 1980s.

The spirit Dyna has seen in critical-care nurses still offers a glimmer of hope.

“It’s not all gloom and doom, because there are always, always people out there who surpass whatever obstacles are put in their way and they overcome. There will be hard times, but they’ll get through.

“And I think nursing is one of those professions that has the ability to attract people who will allow it to get through. I’m looking forward to the day when it is more egalitarian.”

• • •

Kirk was 29 when he inherited the brand-new ICU in 1966. He saw intensive care as an “intellectual challenge,” a chance to build teams of respiratory technicians, physiotherapists, pharmacists, dietitians and engineers who could work holistically with patients and even develop new technology.

When he took over, Kirk quickly learned “that you had to treat all the people that worked in the unit — the nurses, the respiratory therapists and so on — as part of a team. And that was quite different from the way things were back in the ‘60s, where physicians were kind of little overlords. They’d make rounds usually just with the head nurse and they were pretty autocratic.”

The whole team went on daily rounds with bedside nurses and doctors, and they affectionately nicknamed their leader Captain Kirk. He didn’t mind the Star Trek reference. He was taking them into a new frontier.

“I was at the advancing edge of a new discipline. We were discovering new things and inventing new equipment all the time. We had a great group of people that supported each other to work with, and at least at that time, there was very little interference and very little politics. It was just a great time to work.”

“If an ICU is going to be successful and is not going to have a high turnover, you’ve got to, first of all, properly educate your nursing staff. And then you have to treat them like colleagues and respect them, and if you don’t do that, they burn out really quickly and they leave and go somewhere else.” – Dr. Kirk

In the decades since, he has avoided peering for too long back over the figurative wall he built to separate his work from his life. But he knows what it will take to carry intensive care into the future. It’s all about the people who work there day in, and day out.

“Dealing with dying patients is a stress, a big stress for nursing staff, especially, because they’re so involved with them on a personal basis, much more so than the physicians. They’re touching them, they’re looking after all their basic needs. It’s a very personal relationship that a nurse has with a patient, more than a doctor,” Kirk says.

“If an ICU is going to be successful and is not going to have a high turnover, you’ve got to, first of all, properly educate your nursing staff. And then you have to treat them like colleagues and respect them, and if you don’t do that, they burn out really quickly and they leave and go somewhere else.”

katie.may@freepress.mb.ca Twitter: @thatkatiemay

Katie May is a general-assignment reporter for the Free Press.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.